Cryptocurrency vs. Stocks

Cryptocurrency vs. stocks really has its root in where we are in the global debt cycle, fiscal and monetary policy, money, credit, and the role of the dollar and other reserve currencies going forward.

The short answer in the cryptocurrency vs. stocks debate is that they’re both viable as stores of value to grow and protect wealth over time. It’s a matter of how well it’s done.

We covered the notion of how to think about balancing cryptocurrency in a portfolio against other assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, gold) in a separate article.

The more nuanced answer of cryptocurrency vs. stocks has to do with their natures, which dictates how they act in different environments, and what the drivers of those environments are (mainly growth and inflation outcomes relative to expectations).

The price of anything moves because of money and credit flowing in and out of it. The two biggest levers controlling these flows are monetary policy and fiscal policy.

What is a currency?

A currency is a:

- medium of exchange

- store of value, and

- typically, but not always, controlled by a government

Anything can be considered a currency, but the unit of accounting is generally controlled by a government, which tries to control all money and credit within its own borders.

Before the US dollar was the world’s top reserve currency (from being the world’s dominant power after World War II in 1945), there was the British pound. Before the pound, there was the Dutch guilder, and you can go on before that.

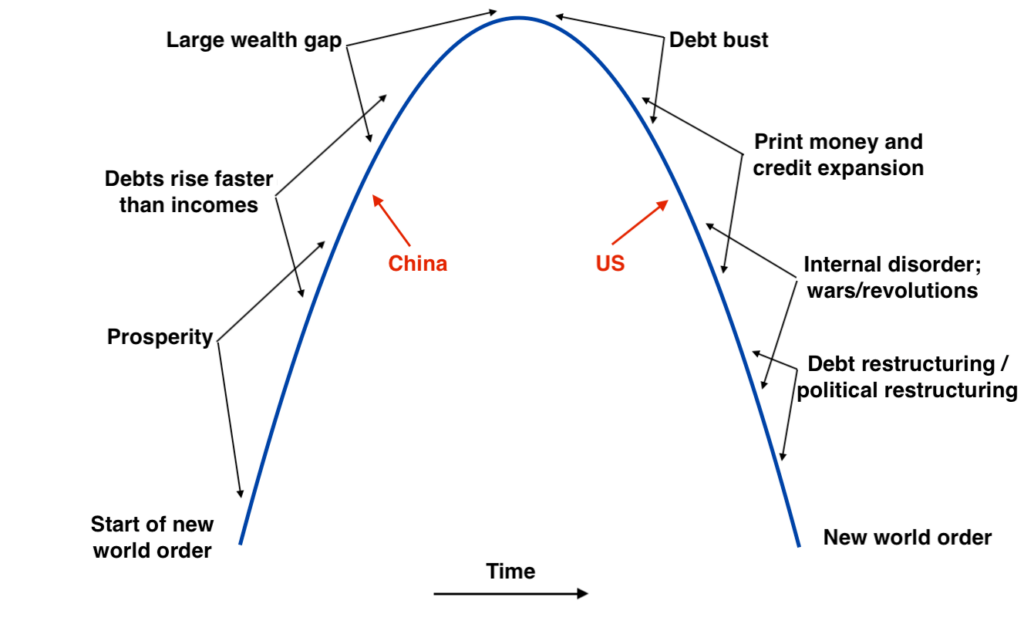

There’s a cycle to all empires that we’ve covered in other articles – why they rise and decline, and the current issues that the US and China are going through, which occurs over and over again.

It’s probably important for most traders to understand the “big picture” components as it limits surprises and provides context for why certain assets are performing the way they are and, most importantly, what’s likely to come next and what to do about it.

A country getting a reserve currency – through its dominance in trade, technology, economics, military, and geopolitical power – then overspending it, and seeing a decline in its currency due to overindebtedness and deteriorating fundamentals, is a classic problem that occurs throughout history.

The financial component to these cycles. Governments tend to spend beyond their means given what the incentives are.

Deficits mean the creation of debt. Debt means bonds. Bonds are instruments that have to be sold to buyers (domestic, international) in order to fund these deficits.

When there’s the lack of buyers for the bonds, there’s either:

a) a rise in interest rates (which hurts credit creation and thus economic activity), or

b) money can be printed, which hurts the currency

As this is playing out:

- the government running perpetual deficits

- spending beyond its means

- the realization that there’s not enough productivity spread evenly enough…

…there’s an internal clash and social cohesiveness issue that goes on.

There are wealth gaps, opportunity gaps, values and ideological gaps, and social and political gaps that grow. So there’s more societal discord.

Often along with this, you generally have a rising power coming up to challenge an existing power, which creates external tensions.

In modern times, this means China coming up to challenge the US and there’s conflict along various dimensions:

i) trade and economic

ii) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military

These conflicts will have big implications for capital flows and capital markets in the decades to come.

These all tend to go together because it comes down to the basics of the strength of a country.

The financial part (deficits) creates credit (debt), which creates buying power. It’s a short-term stimulant.

But when overdone, it’s a long-term drag because it’s not just borrowing from a lender (the entities that buy the bonds), but a country borrowing from its future self because that has to be paid back one way or another.

Every time the economy gets weak, the money and credit creation goes into overdrive. This creates a short-term stimulant but that pile of debt builds up over time.

And they keep doing that until it gets more and more difficult. Once you get down to about a zero percent interest rate, you can no longer stimulate the economy in the normal ways.

And to continue stimulating, then sound money (offering positive inflation-adjusted interest rates on money and bonds) generally goes out the window.

Moreover, the pile of all the debt being created (and other financial securities) is somebody else’s assets.

All of those assets are claims on goods and services. Those have to be created for those assets to hold their value over the long-run.

We tend to think of “wealth” as financial assets. But those financial assets don’t have any purpose other than to sell them at a point in the future to get goods and services out of them.

When the pile of debt and assets becomes very large and there aren’t the incentives to hold all that, then it becomes a problem.

In the old days, financial assets were a claim on gold (or something tangible), which was considered money, which could buy things.

When you have too many claims on money, then money has to be devalued and money no longer goes as far.

1945

The cycles generally start with a conflict. There’s a winner to that conflict and they set the rules.

The archetypal rise and fall of an empire (currency strength/weakness typically lags each step)

The end of World War II in 1945 started the American world order. That started the beginning of the dollar as the world’s leading reserve currency. And the dollar was connected to gold.

Money wasn’t what it is now (fiat). Paper money (bank notes) was essentially like a check that you could cash in to get some amount of gold.

The privilege of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency meant many entities wanted to hold dollars globally. That meant having the capacity to spend and derive an income effect from it (from the cheaper borrowing associated with that desire to hold dollars).

As is naturally the case, the US used this advantage profligately, spending more than it earned. Liabilities built up relative to assets. Those who had dollars cashed them in for gold and gold reserves declined.

This problem came to a head in August 1971, when President Nixon diplomatically announced that the claims on gold were too high. So, the US unilaterally broke the dollar’s link to gold.

Money was no longer gold-based, but fiat-based.

That got more money and credit (a claim on money) into the system. That was good for gold (priced relative to dollars), good for stocks, and good for commodities and other currencies/stores of value.

It was bad for bonds because it devalued debt (a promise to deliver money).

We’re in a similar situation now. There are a lot of liabilities and not enough money. So the government creates money and credit to relieve that pressure.

This is good for most financial assets, but there’s a constraint on that when rates approach zero.

Cash has about a zero rate (or negative rate depending on where you go), but there’s a positive inflation rate and central banks are always going to target at least a zero percent inflation rate.

That means that cash is a wealth destroyer because its real rate is negative.

This also spreads to bonds – i.e., money delivered over time – and locks in the bad real returns. You also have considerations like taxes to deal with on any interest earned.

Supply and demand issues in the bond market

Fundamentally, you have a supply and demand issue for all the debt and liabilities (financial assets – i.e., claims on goods and services).

Looking ahead, because of the deficits, we know we’re going to need a lot more money and issue a lot more debt to fund all the obligations.

This causes the printing of money. Moreover, policymakers want taxes to go up when the government is chronically short on funding and the problem will get worse.

Then people want to get away from these measures so you start to see capital wanting to go elsewhere due to low yields (forward returns), and more onerous tax policies.

Policymaking becomes more difficult as money leaves the country. You get less output per unit of inflation. So that creates the greater possibility of things like capital controls.

Sometimes you even see the implementation of price and wage controls, but they tend to create distortions rather than alleviate problems.

Naturally, this is how the cycles go.

Where does that capital go?

It generally goes to almost anything else but the wealth destroyers – i.e., the cash and bonds of the countries with intractable problems.

It goes toward:

- other countries

- other currencies

- commodities

- tangible assets (real estate, collectibles)

- gold and various forms of precious metals that are not controlled by any government, and

- practically anything that can be considered a store of value

When money and debt are created it’s good for most assets – stocks, gold, commodities, real estate, and new forms of store of value assets like cryptocurrencies and other digital assets.

Cryptocurrencies are conceptually just like alternative currencies that have always existed. They are just in digital form.

What’s really happening when a lot of these assets are going up is the money is losing its value relative to these assets.

For example, gold is a long-duration, non-fiat, store of value asset. It has imputed value because of its characteristics. When gold goes up, gold is still just gold. Its intrinsic value hasn’t increased – or decreased when it goes down.

It’s merely reflecting the value of the money used to buy it. When gold goes up, money’s value (in whichever currency it’s denominated in) is going down in gold terms, which means gold rises in money terms.

It’s an alternative type of cash – basically a volatile, inverse of money.

The desire to hold alternatives – and considerations and debate over what those alternatives are – is the part of the cycle we’re in now.

There are all sorts of things rising in value – basically everything except cash and bonds – and includes things like various forms of collectibles and non-traditional assets (e.g., baseball cards, rare fossils, rare liquor, and so on).

Different types of inflation

Many assets – like gold, bitcoin, commodities, some stocks, real estate, other stores of value – are perceived to be inflation protection assets in some form (many of them in an imperfect way).

There are also different types of inflation.

One is more of the traditional kind of inflation where the demand for something presses up against its supply and you get that type of inflation. This is commonly applied to labor and goods and services, but can be applied to commodities, and anything “real” where there’s a market for it.

This is generally when a central bank is less accommodative of easier monetary policy and begins hiking interest rates to slow down credit creation.

There’s another type of inflation – the monetary type. This comes from the supply of debt being too high, so they produce more money.

The holders of all those financial assets, notably bonds (because bonds are a promise to receive money that a central bank can just print), they’re going to be less inclined to hold those.

So, where does that money go?

If you hold a bond but the yield on it is no longer good enough for you, generally you want to hold something similar to what you previously owned.

So you might go into a longer-duration type of debt, corporate debt, and eventually into stocks. This is generally the behavior when policymakers lower interest rates further and further and depending on how far they push quantitative easing programs.

Much of it boils down to:

a) Who gets the money?

b) And what do they do with the money?

In the world we’re in, where the fiscal policymakers direct more of the economy, it can be more targeted. Politicians can target who receives money and who doesn’t receive it. And they can change who is taxed and how much.

The inflation of the 2020s is closer to the inflation of the 1971-1981 period, when the gold link was broken to get more money and credit into the system.

That bids up investment assets and you have that type of monetary inflation. It places a lot more emphasis on the idea of where do I store my wealth?

There will be some level of labor inflation. But it’s different from past labor inflation. A lot of “labor” (productive capacity in its various forms) these days is in the form of technology and code. That can be produced with little marginal cost.

But as liquidity is put into the financial system, it has to find good investments. So all investments are bid up relative to cash.

As asset prices rise, their future expected returns go down. That shrinks their returns relative to cash. Carry trades become riskier. People start to contemplate where else they can get returns.

When the spread has largely been taken out of riskier financial assets, then that process of easing policy through the financial system (through lower interest rates and QE) can’t be pushed much further.

It’s also hard to tighten monetary policy because the entire system is dependent on the low interest rates.

And low interest rates lengthen the duration of financial assets, so raising rates even mildly (or even the implication of such) can send shock waves through markets.

So it seeks a home in other places – goes into houses, collectibles, other countries with better returns, and newer things like cryptocurrencies.

Portfolio outcomes from the last period of US inflation (stagflation)

In the 1970s, due to monetary inflation, all financial assets had negative real returns – cash, bonds, and stocks – even though nominal returns were fine. Commodities and gold were the big winners as alternative stores of value.

Owning these alternatives helped portfolios prevent their returns from being negative in real returns.

60/40 Stocks/Bonds

If you looked at a 60/40 stock and bonds portfolio from the 1970s, it did fine in nominal terms, but poorly in real terms.

| Year | Inflation | Portfolio Return | Balance | Stocks | 10-Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 3.41% | 11.52% | $11,152 | 17.62% | 2.35% |

| 1973 | 8.71% | -9.60% | $10,081 | -18.18% | 3.29% |

| 1974 | 12.34% | -15.07% | $8,562 | -27.81% | 4.05% |

| 1975 | 6.94% | 24.90% | $10,694 | 37.82% | 5.52% |

| 1976 | 4.86% | 22.00% | $13,047 | 26.47% | 15.29% |

| 1977 | 6.70% | -1.80% | $12,812 | -3.36% | 0.53% |

| 1978 | 9.02% | 4.78% | $13,423 | 8.45% | -0.74% |

| 1979 | 13.29% | 15.28% | $15,475 | 24.25% | 1.83% |

A 60/40 stocks/bonds portfolio gained about 55 percent total in nominal returns from 1972 through 1979. (1972 is chosen because it was the first full year that the US went off the gold standard).But inflation grew by 87 percent, leaving negative real returns of about 32 percent.

In other words, the real purchasing power of that portfolio fell by about one-third. That’s a lot to give up.

It seems like you would have made money, but you would’ve been squeezed because the prices of the things you have to buy went up by more. Making money in nominal terms is not enough in trading or investing. You need to at least preserve your purchasing power.

Adding in alternative stores of value

However, if you reduced the bonds portion by 10 percent (recognizing their negative real rates for most of the decade) and allocated that 10 percent to gold as an alternative, you would have returned 110 percent, leaving real returns of about 23 percent.

You preserved your purchasing power and added a bit more.

| Year | Inflation | Portfolio Return | Balance | Stocks | 10-Year | Gold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 3.41% | 16.18% | $11,618 | 17.62% | 2.35% | 49.02% |

| 1973 | 8.71% | -2.63% | $11,313 | -18.18% | 3.29% | 72.96% |

| 1974 | 12.34% | -8.86% | $10,310 | -27.81% | 4.05% | 66.15% |

| 1975 | 6.94% | 21.87% | $12,565 | 37.82% | 5.52% | -24.80% |

| 1976 | 4.86% | 20.06% | $15,086 | 26.47% | 15.29% | -4.10% |

| 1977 | 6.70% | 0.41% | $15,147 | -3.36% | 0.53% | 22.64% |

| 1978 | 9.02% | 8.55% | $16,443 | 8.45% | -0.74% | 37.01% |

| 1979 | 13.29% | 27.75% | $21,006 | 24.25% | 1.83% | 126.55% |

You also had much lower drawdowns, lower left-tail risk, lower underwater periods, among other things.

Making that change in portfolio construction is simple and overly basic, but it conveys the general point.

Similar environment today

In the US, we’re in a similar monetary environment to the 1970s with negative real rates and the ambition to let inflation run a bit hot. Adding inflation protection assets (i.e., stagflation assets) can provide a lot of value.

This is not just gold, as in the example. Gold can be a piece of a portfolio. But there are many things that can be considered a strategic alternative or store of value in that it should help a portfolio at least retain its purchasing power.

- Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

- Gold and other forms of precious metals (e.g., silver, palladium)

- Commodities (industrial, agricultural/soft)

- Other countries with more normal cash and nominal bond rates

- Stocks that can act as a type of bond or fixed income replacement (e.g., consumer staples)

- Private businesses that aren’t overly cyclical or could benefit in a higher inflation environment

- Collectibles

- Riskier ventures where there’s a higher prospective return (startups, angel investing, venture capital)

- Alternative asset classes like cryptocurrencies and DeFi instruments

First step in asset allocation

Your first step in deciding what to hold is to look at where wealth is being destroyed.

Wherever wealth is being destroyed you have to avoid that.

For example, most sovereign debt in the developed world yields a negative real rate. It yields anywhere from negative yields to small positive yields depending on where you are and the duration of it. Long-duration US debt has the highest yield, but there’s a lot of volatility to it plus a higher inflation rate.

The world is overweight dollar-denominated debt based on various measures of what an entity would want to hold to remain balanced.

For example, the USD is around 60 percent of global FX reserves and debt yet only 20 percent of global economic activity.

That pile of debt and other non-debt liabilities also has to grow. The US has deficits.

The expansion of that pile means lower real rates will be kept on the debt to make sure the debt servicing isn’t a problem.

With more debt, you either need:

- Lower interest rates

- A lower currency, or

- More productivity

…in order to grow out of it.

And it’s impossible to grow out of because of the sheer size of it, adding up not just the debt but non-debt claims.

So you know you need lower real rates (or risk economic destruction) or a lower currency.

The low real rates are not attractive to domestic buyers. And the lower currency is not attractive for international buyers.

In short, the amount of bond issuance will go up, and their real returns will not be attractive. And for various reasons people don’t want to buy those bonds.

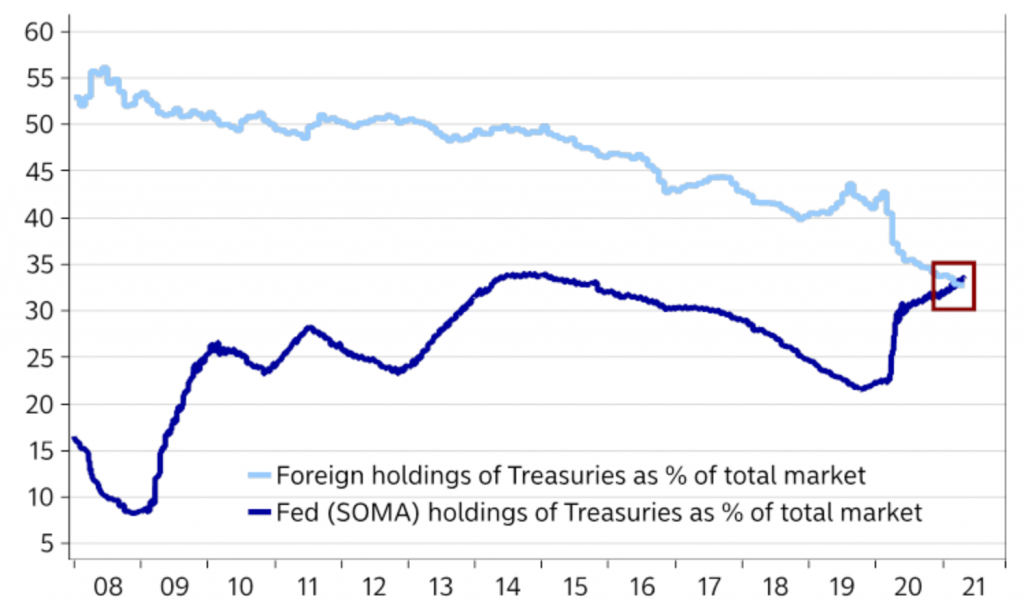

The Federal Reserve now owns more bonds than international buyers due to the lack of free-market demand for them.

Fed ownership of the US Treasury market vs. Foreign ownership

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

So all that money will seek other assets in whatever form. That can include certain types of stocks and cryptocurrencies. It can include many types of things that can be considered a store of wealth.

The influence of the growth of China on capital markets

At the same time people are looking within their domestic stock markets and in things like crypto to deploy their capital, there’s the growth of China. Their rise is making them a more effective competitor for capital.

China, in 2015, had only two percent of its markets open to foreigners. Now that number is north of 60 percent.

And the relative pricing between China (and other parts of Southeast Asia) and developed markets is different.

China has a normal cash rate, normal yield curve, and normal financial asset pricing. They still have the normal policy levers.

The US and the West are much more pressed against the normal barriers.

Institutional investors and central banks will view themselves as underweighted in the East and overweighted toward US and other developed market assets.

With the flood of debt assets coming forward from the US, the US is only going to be able to attract enough buyers of that by either raising interest rates or devaluing the currency by having to buy up increasing amounts of its own debt.

Raising the interest rates isn’t practical because financial asset prices and keeping the economy going is dependent on that.

So the dollar will have to devalue, which will incentivize various types of investors and capital allocators to move over into alternatives of different forms.

A big wealth shift is going on.

China is not just a competitor on trade, economics, technology, and geopolitics, but also a capital competitor that will compete for global resources.

The appreciation of the yuan / renminbi

All of this is also supportive of China’s currency.

If people want less US debt and more China debt, that’s supportive of the CNY and less supportive to the USD if capital isn’t flowing to that asset.

China is also a bigger part of global trade than the US. That gives them the capacity to invoice in their currency or lend in its currency.

China has been reluctant to do so because it wants to avoid conflict with the big powers, especially when its military and technology were not yet up to par.

Now that that’s developing, they’ll be more willing to push its currency internationally.

The digital yuan was one such step to better internationalize its currency, though it’s currently focused on the domestic retail market. This provides an additional channel for policy transmission.

The arc of the rise of China and the renminbi is following the same type of pattern as what happened with the Dutch guilder, British pound, and US dollar and those empires.

Cryptocurrency follows past trends

We tend to think of cryptocurrencies as something entirely new, and they are due to the digitization aspect, but the notion of alternative currencies as a store of value goes back thousands of years.

Before Sweden in 1668 (Riksens Ständers Bank) no country even had a central bank.

There was competition among many public and private currencies, as well as other forms of physical objects (e.g., gold, silver) that could be used as ways to effectuate a transaction.

Before Sweden, and later England and other countries, came up with the idea of a central bank to establish a monopoly on money and credit, various currencies competed with each other.

There was the idea of what can be considered a transaction medium and store of value. An economy basically boils down to a series of transactions. You can exchange goods and services for goods and services, but it’s impractical most of the time.

It’s easier just to exchange money to facilitate the transaction. The entity that gets money can go buy what they want (or save in the currency), and so on.

Central banks helped bring forward the notion that there will be one currency within a country or territory’s borders. This helps give greater control. One of the greatest powers a government has is control over its currency and the credit creating capacity of the economy (i.e., through changes in interest rates and money supply). And to be able to control where that money and credit goes.

How do policymakers have control when alternative currencies pop up?

When other types of currencies become popular in a country, then it’s a matter of how governments decide to treat those.

Do they accept them? How big do they have to become before they start cracking down?

If money and credit is just going into other currencies and stores of wealth then it defeats the purpose of having that control. Decentralized currencies take away power, which is bitcoin’s (and other cryptocurrencies’) biggest risk.

Even gold has been banned throughout history by governments when it became competitive with the currency they wanted to control.

Gold ownership was illegal beyond certain use cases (e.g., jewelry, collector coins) in the US from 1933 to 1975 (certain restrictions lifted in 1964).

Capital controls become more of a common policy choice when governments have difficulty keeping control over their currency. The US is such a spot currently with very low nominal rates and negative real rates provided on its currency and bonds (currency delivered over time).

If a country doesn’t offer enough interest on its currency and bonds, then that capital leaves. Capital leaving makes policy trade-offs more acute. So governments will often turn toward capital controls to prevent that money from leaving.

The hoarding of ‘good money’

When a more valuable currency enters circulation it tends to be hoarded.

For example, the Coinage Act of 1965 involved replacing silver as the base metal for most coin creation. Cheaper metals or composite mixes were used from 1965 forward.

For example, the pre-1965 half-dollar had 90 percent silver. The 1965 half-dollar had 40 percent silver.

Both were accepted as 50 cents when making purchases because of their equal assigned values, though the pre-1965 coin had a higher intrinsic value. People realized this and began taking it out of circulation.

Because of this intrinsic debasement in many coins (e.g., dimes, quarters), the pre-1965 coins gradually disappeared from the public as their intrinsic values went above their imputed values.

The “good money” gets hoarded (e.g., melted down and sold if their intrinsic value is higher than face value) or goes somewhere else (e.g., become part of international trade where legal tender laws can be skirted) while the “bad money” stays.

Preferred currencies

There’s always been a preferred currency globally. Traditionally, it’s been gold and, to a lesser extent, silver.

It’s tangible and has value associated with it due to its rarity and special properties (the way it can be molded at certain temperatures).

Gold (and silver and other precious metals) can’t be controlled. Once you have it, there’s practically nothing a government can do about that. They can’t print more of it like their national currency. More can be mined to increase global supply, but it’s a slow and costly process. It can lose its value to some extent, but it’s nobody’s liability.

According, you don’t have to be worried about being devalued on.

This is a strength of many cryptocurrencies as well. The supply of many is capped, though others are not and there’s no limit to how many can be created.

But the world’s reserve currency – usually the top national currency – has held special importance.

The US dollar has been that for a long time. In countries with unsound currencies and high inflation, reserve currencies tend to be hoarded.

Currencies to be held in times of conflict

But in periods of conflict, nobody is really that comfortable holding different currencies.

Russia announced it didn’t want to own dollars in June 2021 to help get around sanctions.

China will also be reluctant to hold dollars due to that geopolitical conflict.

The best cryptocurrencies for the individuals are not the best ones for the government

Bitcoin’s biggest risk is its success. Right now, it’s not a big enough deal to crackdown on it in a big way. A market that’s, for example, around $1 trillion is less than 5 percent of US GDP and less than 1 percent of global GDP.

A lot of people were to lose money if it were to lose most of its value, but it wouldn’t harm the whole system.

If it gets to a point where people want to sell bonds and buy bitcoin or something else, that’s a risk to that asset because the government has less control over policy if money isn’t going into credit and other dollar-based assets.

What’s controlled and what’s not?

A lot of it comes down to what’s controlled and what’s not controlled.

Governments can purposely make currencies and their bonds bad investments to effectuate their policy goals. This is good for governments but bad for the individuals and entities holding them.

Gold, bitcoin, and other stores of value (e.g., diamonds, certain commodities) aren’t controlled. National currencies, of course, are controlled by the governments that create them.

And you might also get some form of international controls on these rules.

When it comes to things like cryptocurrency regulation, for it to be effective, there will need to be some level of international cooperation. Otherwise the activity will simply go to the places where regulation is more lenient or non-existent.

The same logic also applies to taxation. If a country is trying to get more tax revenue, but their measures cause companies, people, and assets to simply go to the low-tax jurisdictions, then it defeats the purpose.

Cryptocurrencies will be competitive with each other on many fronts:

a) Store of value

b) Transaction medium

c) How many transactions they can accommodate

The government having the ability to effectively control cryptocurrencies, or any digital currency or asset, is main worry those who own them.

Governments know how transactions are taking place and they probably have the capacity to stop them.

For example, the vast bulk of transactions happen through exchanges where payment is provided by linking a bank account. So if governments can shut off that infrastructure between the banks and exchanges they can effectively shut down cryptocurrency transactions.

Mining, however, can be anywhere and can spring up anywhere there’s energy.

How cryptocurrencies are owned is another big risk. There are ways to own bitcoin “off the grid” – such as cold storage, though most of it isn’t owned in this way.

The debate is not only cryptocurrency vs. stocks vs. something else

It’s important to avoid 0-or-1 thinking in terms of which currency or asset will be the winner.

We don’t know ultimately which national currency will turn out to be the big winner 10 or more years from now.

Or whether bitcoin will remain the top cryptocurrency in 10 years. Or whether it’ll be something else.

The reality is that all currencies have devalued or died over time.

Gold and precious might be the exception, but even they have their own issues with volatility and big ups and downs over history. They are only currencies in a small way. They don’t have the capacity to take in large transfers of wealth.

Total debt – one person’s debt is another person’s assets – is hundreds of trillions of dollars globally, whereas the gold market is about only $5 trillion taking the market above a certain high level of purity and excluding jewelry, central bank ownership, and non-private owners.

The same “evolve or die” reality goes for companies, empires, and many other things.

That’s the process of how evolution and adaptation goes.

We can be open-minded and recognize that there’s a lot more that we don’t know than we do know, and can own plenty of different things in light of this.

The main thing is having the appropriate diversification of the alternative currencies and spread one’s bets widely to improve return relative to risk over the long run.

The risk of overconcentration in dollars

For most Americans’ lifetimes, the dollar has been the world’s reserve currency and the privilege that comes with that.

After World War II, the US had 80 percent of the world’s gold (which was money). They won the war, had nuclear weapons, and had the most dominant military.

The US used that privilege to great effect, overextended itself financially, and is in the process of declining in relative influence.

But if you go back 200+ years and go decade by decade in each country, you would see that concentrating your wealth in any asset class would have seen losses of 50 to 80 percent or more.

This includes stocks, bonds, and cash. If you were a German, your wealth was wiped out twice in the first half of the 20th century.

If you were Japanese, you would have experienced a near-total wipeout.

If you were British, you may have been part of winning major global conflicts, but the pound was significantly devalued as it lost its status as the top reserve currency.

If you were an American in the 1920s, you couldn’t have foreseen what was coming in an era of fast growth and great prosperity.

You can go to various emerging markets that also experienced wipeouts over and over again (e.g., Argentina).

It’s not just a currency matter, but taxation eats up returns and there are also conflicts over power and wealth – internal and external – that influence that as well.

Protecting wealth

So when it comes to protecting and growing wealth, something like the 60/40 portfolio that’s concentrated in your home market and home currency contains a lot of risk.

If there are new stores of value and new inventions, like cryptocurrency and decentralized finance assets, then it’s natural to have interest if they’re genuinely an extra viable source of wealth protection.

You’ll have governments against these things because they can undermine their control. But there will be demand for them.

Final thoughts

When cash and bonds have negative real rates it means they’re a source of wealth destruction. Negative real returns can also spread to stocks if multiples stay high enough and inflation runs above their yield.

The 1970s in the US were an example. Cash, bonds, stocks returned positively in nominal terms, but negatively in real terms. A 60/40 portfolio lost one-third of its purchasing power from 1972 through 1979 even though it gained 50 percent in nominal terms.

If you took 10 percent of that “40” from bonds and put it into gold, your nominal returns were 110 percent and real returns were 23 percent. This simple change gave you 55 percent aggregate higher returns.

People look for alternatives in this kind of environment. That’s traditionally gold, metals, and commodities, but can be other things.

Collectibles, cryptocurrency in smaller amounts, other countries and currencies with normal cash and bond rates, certain types of stocks and private businesses, startups, some types of real estate…

Over the long run, cash is the lowest yielding asset because of inflation. Low interest rates in developed markets make bonds in those markets less attractive. Real returns are negative so your wealth gets destroyed in those.

And the pile of those bonds is going to keep getting bigger with the huge deficits.

All of that money naturally spills over into other types of assets as people seek to protect wealth.