How Empires Rise and Fall

Economic cycles and how they operate, which are the main drivers of asset prices, are heavily a function of productivity and indebtedness.

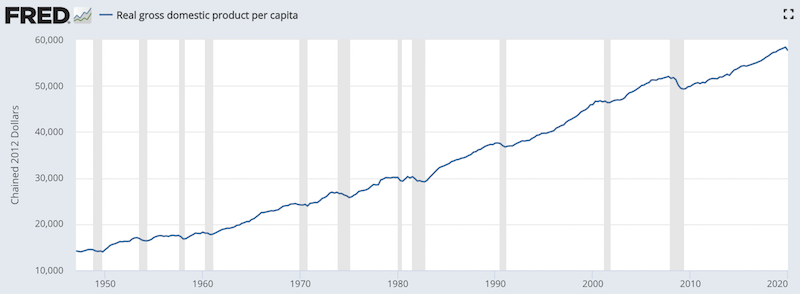

Productivity rises over time as people learn, invent, and create. Productivity is not a purely linear thing, but is relatively stable over time. It much less volatile than the cycles involved in credit creation and destruction. This is the US productivity trend since the end of World War II.

(Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis)

As a whole productivity is not volatile enough to have a material effect on asset price volatility. It is, however, what matters most in the long-run.

Asset price volatility is heavily a function of the expansion and contraction of debt.

While productivity and debt are the main drivers of economic activity, it is heavily people’s choices that determine their levels of productivity and indebtedness. Accordingly, psychology and culture is of large importance in determining why some countries succeed (and why they’re good places to invest) and why some countries fail (and why they’re bad places to invest).

Psychology and culture drive people’s attitudes toward work, leisure, borrowing, spending, and how they approach conflict. Different experiences lead to different psychological biases. As countries and empires go through their life cycle, certain cause-effect linkages occur to drive these changes lead to why some succeed while some fail. While there are many commonalities, no life cycle is exactly the same.

How Empires Rise and Fall

Economic conditions influence human nature and human nature influences economic conditions.

Broadly, there are five stages to the average life cycle of a country or empire that involve the interplay of the broad reality of circumstances and perception of their circumstances.

i) In the first stage, countries are poor and perceive themselves as poor.

ii) In the second stage, countries are wealthy and perceive themselves to be poor.

iii) In the third stage, countries are wealthy and perceive themselves as wealthy.

iv) In the fourth stage, countries become poorer, but they still perceive themselves as wealthy.

v) Finally, in the fifth stage, countries undergo decline, and they become slow to accept the new reality.

We’ll go over each individually.

Stage I

In this stage, countries are poor and perceive themselves as poor.

These countries are undeveloped. They primarily have subsistence lifestyles and low incomes. They tend to value money a lot and not squander it. Because they have low savings and low incomes few investors are willing to lend to them, and their debt levels are low.

Some remain in this stage and others move out of it.

Culture is a big part of whether they do – do they have the drive to succeed and compete internationally? Geography plays a role in many cases as well.

There are dispersions within countries. For instance, within China it is not realistic for many citizens to achieve incomes that are on par with those in developed countries. They are too far removed from urban centers, which are the hub of where services are provided and are involved in the production of new technologies.

Accordingly, without access to these centers, they cannot compete economically. Moreover, it is unreasonable to expect the average income of a Chinese person to be in line with that of the average person from Beijing or Shanghai for a very long time, let alone have an income in line with that of the average US citizen. (The US also benefits from having the world’s primary reserve currency, which carries an income advantage in the form of being able to borrow more cheaply.)

The countries that eventually make the transition to the next stage typically are able to accumulate enough savings due to having more than enough income needed to survive.

When countries are poor, they usually have higher levels of financial cautiousness. As a result, they have higher savings rates because they are worried about not having enough income in the future.

Countries with low incomes also typically have very competitive labor, particularly if they are educated (e.g., China). With low labor costs, countries that emerge into the next phase typically adopt export-oriented economic models. Namely, they produce low value-added goods cheaply and export them to richer countries.

If countries are low-cost producers and have political stability, they will usually be able to attract ample amounts of foreign investment from companies who want to establish a manufacturing hub there. This provides a cheap source of labor to increase profitability and allows them to export to wealthy countries where consumers benefit from more cheaply produced goods.

Naturally, countries in this first stage need to provide high returns on investment because investing there is risky. Because they can produce at a low cost, they can typically follow through on providing these high returns.

At this stage, their financial economies are undeveloped. Their currencies are cheap are not used as reserves globally and their debt and equity markets are not well developed. In some cases – e.g., countries with state-directed economies, such as the former Soviet Union or North Korea today – capital markets as we know them don’t exist at all.

In these early emerging countries they will commonly adopt fixed exchange rates regimes. This usually means pegging their exchange rates to gold or to a reserve currency. This reserve currency is typically that of the major bloc they sell (or want to sell) their goods to. This is also true beyond early emerging countries.

For example, Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia (among a few other major oil exporters) peg their currencies to the US dollar. Switzerland formerly pegged its interest rate to the European Union given the EU is the country’s biggest trade partner.

Citizens gradually achieve incomes that are in excess of their spending. They commonly save the excess or invest it back into their businesses, personal means of production, or convert the savings into hard assets (such as precious metals, land and/or real estate).

Countries that generate more income and think of opportunities outside their own borders often want to invest money in other countries. This typically starts with the world’s safest investments, usually the sovereign debt of the world’s reserve currencies. Thinking currently, that means the USD (the main one), EUR and JPY (these top three represent about 90 percent of all wealth stored globally), and to a lesser extent GBP, CNY, CHF, AUD, and NZD.

Those in early emerging countries value earning and saving money more than they do spending. Because of this, their government will typically prefer that their currencies remain undervalued. This helps keep their labor and goods cheap to the rest of the world. Accordingly, it helps them build savings at the sovereign level (also known as foreign reserves, mostly through the sovereign debt of other countries).

Countries can move through the early emerging stage quickly (within decades) or never move out of it altogether due to a confluence of factors, such as education, skills, and abilities, culture, and geography.

Stage II

Early emerging countries enter into a new stage of their development (“late emerging”) when they have more money than they need to cover their basic living expenses, and this savings begins to rise rapidly.

The psychology and behavior of the people between early emerging and late emerging countries is similar even when their savings and their ability to invest these savings increases.

For example, not all that long ago, in the 1980s, China’s poverty rate was almost 90 percent. Now, poverty has been nearly eliminated. However, the financial prudence of most Chinese is still high having gone through those deprived conditions.

They still have a culture that favors work over leisure, maintain a managed exchange rate, a high savings rate, high rates of investment back into their means of production, and high rates of investment into hard assets (e.g., gold, land, real estate) and the sovereign debt of reserve currency countries. Much of their economy is still export-based but they are working on an economic restructuring that puts them on the forefront of services and the newest digital technologies (with the aim of helping push them into the next stage).

Their exchange rates also usually remain undervalued, which continues to help their labor and goods remain cheap on the international market. This competitiveness is brought out by a strong balance of payments situation (i.e., how much other countries owe them relative to what they owe to other countries).

Their incomes and assets rise faster (or at least in line with) their debts. The collective balance sheet of the country is very healthy.

Productivity is rising quickly in this stage. Technology that’s already part of everyday life in other countries becomes adopted. When income rises in line with productivity, goods and services inflation is not an issue. Rising productivity levels also helps their competitiveness relative to other countries.

Nonetheless, at some point incomes rise faster than productivity and debts begin to rise faster than incomes.

Income growth leads to “too much money chasing too few goods”. In other words, spending increases faster than supply can be increased through gains in productivity.

Moreover, emerging countries often peg their currencies to those of reserve currency countries. That means they tie themselves to the interest rates of reserve currency countries, which have lower income growth and inflation.

Interest rates must follow trends in nominal growth rates. While low interest rates are appropriate for countries with low nominal growth rates, they are too low for countries that have higher growth and inflation rates.

Emerging countries that have low interest rates relative to their nominal growth rates have high money and credit growth that fuels inflation (because the demand for money and credit is high).

Emerging countries will usually maintain their fixed exchange rate regimes – and therefore linked monetary policies – until the high inflation rates become too excessive, investment bubbles pop up, and the protectionist trade policies undermine efficient market behavior.

The move to an independent monetary policy is what marks the transition to the next stage of development.

The key signs are:

i) rising inflation from income growth and spending in excess of productivity growth

ii) over-investment and asset bubbles (from excessively loose monetary policy)

iii) debt growth in excess of income growth (often by a wide margin)

iv) trade and current account surpluses

A move toward having an independent monetary policy is sign of maturation as well a matter of practicality. Pegged currency regimes that are out of line with the fundamentals inevitably come undone.

If they don’t adopt an independent monetary policy they’ll see one or more of the following effects:

i) higher exchange rate

ii) higher savings (aka foreign exchange reserves)

iii) lowering of real interest rates (which leads to inflation and asset bubbles)

The currency appreciates.

Internationally, because of their trade surpluses, they often have tension with other countries. Their labor is cheap, so low-skilled workers in developed countries often see their jobs off-shored to these countries who will have workers with higher productivity per dollar. This also leads to capital outflows from the developed country into the emerging country as more investment occurs.

Floating the currency and seeing it appreciate helps to ameliorate these issues, and is also something that’s been earned after progressing through the early stages of development.

Floating a currency and letting it appreciate also means that its protectionist policies and export-based economy will be disadvantaged. Its workers will become more expensive and its goods will no longer be as cheap.

Countries want to have an independent monetary policy. It’s the best thing a country can have to adjust levels of money and credit in circulation in light of its own economic conditions (i.e., output relative to inflation).

Because of this, no major developed country has an exchange rate pegged to another’s. Countries that do tend to be small or emerging economies doing so out of practical necessity – either they have trouble managing monetary policy without the peg or will fail to get enough confidence in their currency without linking it to gold or a developed trade partner’s currency.

When they transition into the next stage, it will be apparent by their domestic equity and debt markets becoming more accepted by both domestic and foreign investors. Lending to the country’s private sector becomes mainstream.

By this point, these countries are conspicuously rising in their development by their high savings rates, rapidly rising incomes, typically growing foreign exchange reserves, and modern infrastructure and cities.

When large countries come out of the late emerging phase they are usually emerging into world powers. That often causes conflict with incumbent world powers and can cause a disruption in the world order.

Stage III

At this third stage, countries not only are wealthy, but perceive themselves as such.

Incomes approach levels commensurate with developed countries. Investments into R&D, capital goods, infrastructure, and other tangible assets generate productivity gains.

Those who experienced the poorer times begin to be replaced by those who have only known the better times. As a result, the collective psychology of the country changes. Savings rates begin to drop as they feel less need to be protective of their financial situations and more comfortable spending and savoring the fruits of their new wealth.

This is usually visible through the increased expenditures on discretionary spending and luxuries relative to the basic necessities. Moreover, work weeks become shorter in both number of days worked and the number of hours.

These countries increasingly shift from an export-based economic model to a consumption-based model. They tend to import more from the emerging countries that are the primary exporters, particularly for low valued-added goods.

Investors and businesses in these early stage developed countries look for higher returns by investing in developing countries where labor is cheaper.

The country’s debt and equity markets and its currency become a go-to place to invest by both domestic and foreign investors. Capital raising becomes common, as does financial speculation. The high returns of the past become extrapolated forward. Combined with the development of these markets, this encourages the purchase of financial assets on leverage.

Their growth rates lower and they are typically politically stable and have other characteristics common to developed market (e.g., private property rights). Interest rates decline and so do investment returns relative to emerging markets. Their markets increasingly become perceived as safe.

Any country in this stage that’s of a large size typically becomes powerful economically, militarily, and technologically.

Military development increases as it becomes a necessity to protect their interests globally.

Before about halfway through the twentieth century, countries in this stage of development would take control of foreign governments and effectively turn them into colonies, making them a part of their empire. The countries they took control of would provide cheap labor and other resources to help the empire remain competitive.

Since the US became the top economic and military power after World War II, this paradigm changed. Instead of requiring control of foreign governments, international agreements have provided access to labor, resources, and investment opportunities.

Stage IV

In this stage, countries become poorer yet still perceive themselves as wealthy. They become late stage developed economies.

Debts rise relative to output and incomes until they can’t any longer. (This is typically when interest rates hit zero and pushing money and credit out into the system becomes significantly more difficult.)

Those who were more financially cautious in the previous two stages of development are either no longer around or play less of a role in the economy. The period of greater wealth creates a collective psychological shift.

They are used to spending and consuming and using debt to make purchases of goods, services, and investment assets. Living these lifestyles, they are not as concerned about not having enough money to get by.

The country’s labor becomes more expensive, which makes them less competitive internationally, particularly for low value-added jobs, which largely go off-shore. Growth rates in their real incomes decline.

As income growth rates decline, they struggle to keep their spending in line with their incomes, as they’ve become accustomed to a certain level of growth. Their spending remains robust, but their savings rates decline and debts increase. The increasing debt to income ratios cause their balance sheets to worsen.

Moreover, productivity gains decline due to less efficient investments in R&D, capital goods, and infrastructure. As infrastructure becomes older, it becomes less efficient and often either difficult to replace or becomes a low priority to replace or update. Oftentimes funding becomes a concern for large-scale public investment projects as deficits become larger.

Countries in this stage have reserve currencies (particularly if they are large), which makes funding deficits easier with cheaper borrowing rates. However, as their fiscal and balance of payments situations worsen and long-term liabilities increase, they rely more on their reputations rather than their actual financial health and overall competitiveness.

Protecting their global interests through military power becomes a big part of their spending and sometimes requires wars.

At this stage, it is common (though not always true) for these countries to run both a current account deficit and fiscal deficit.

Investors also bet on current trends continuing on even when they’re unlikely to do so. This means bubbles tend to occur frequently. Investments that have done well are assumed to be good ones rather than more expensive ones. They take on debt to fund purchases of financial assets beyond their ordinary means. This drives up their prices and reinforces the bubble. This also affects various constituents in the economy – not just investors, but business owners, individuals, policymakers, and banks and other financial intermediaries.

Rising asset prices help investors increase net worths, which helps the process of increasing spending, incomes, and increases in the capacity to borrow. This further supports the ability to buy assets on leverage, increasing their prices, and so forth, until the bubble bursts.

Bubbles can no longer sustain themselves when the cash flows produced by the investments aren’t adequate enough to service the debts and no new capital is flowing in to support further price increases in the market.

In the beginning, bubbles are usually made possible through central banks allowing for overly easy monetary policy. Central bankers mostly focus on inflation and growth and achieving the right balance between the two. Inflation and growth are important, but they typically don’t pay sufficient attention on debt growth as it pertains to output, another important equilibrium. Debt can’t increase faster than output indefinitely. Central banks reining in bubbles by tightening monetary policy is often what pops them.

Financial asset prices impact incomes, net worths, and creditworthiness. Therefore, when asset prices fall there’s a negative feed-through into the economy and into the country’s financial health.

Sometimes, it’s wars that derail countries at this stage (particularly true if these conflicts are lost). Sometimes it’s bubbles in goods, services, and/or financial assets. And sometimes it’s both wars/external conflict and financial bubbles that cause an economic and geopolitical decline.

The most typical characteristic of this stage is an accumulation of debt and long-term obligations that can’t be paid back in money that holds its value.

Countries that go through crises related to their debt situation inevitably see their central banks print money to counteract them, though this comes with a long-run cost.

When large countries go through this stage, it usually means they are approaching their decline as great empires.

Stage V

In the last broad stage of development, countries need to reduce their debt to output ratios and will undergo a relative decline even if they haven’t come to terms with this reality.

When bubbles deflate, countries are forced to reduce their debt relative to their incomes. They can do this in four main ways:

i) Write-down or restructure the debts. When debts are written down, they can make a new agreement to pay a fraction of it or none at all. This is painful because one person’s debts and are another’s assets. So, people believing they hold an asset see wealth they thought they had partially or fully wiped out.

Restructuring the debt might involve changing the interest rates on it to improve the serviceability. They might extend the maturity of the debt to give themselves more time to improve their situation. The might also change whose balance sheet it’s on. These are the main processes that countries, companies, and individuals go through to help themselves manage debt that’s gotten them into trouble.

ii) Austerity. Cut spending to get it back in line with income and prevent debt to income ratios from continuing to increase. This is also hard to do. People, businesses, and other governments rely on government spending as income. Governments that try to impose austerity are not politically popular.

iii) Wealth transfer payments. Wealth transfers involve money from those who have it to those who don’t.

Governments trying to earn more income so they can more effectively distribute it – such as higher tax rates on the wealthy and better social programs and safety nets for the poor – has its constraints. The wealthy want to be protective of their assets and try to move themselves and their assets elsewhere; so, governments could lose these big taxpayers if their rates are not competitive.

Sometimes governments opt for wealth taxes, which are inefficient and not common because most wealth is illiquid. Moreover, in a crisis when bubbles burst and asset prices fall, the upper classes lose large amounts of wealth as the primary owners of financial assets. In the context of debt crises, wealth transfers rarely happen at a scale that make much meaningful difference to rectifying the imbalance of supplying money to those who need it most in relative terms.

iv) Money creation and debt monetization. Central banks create money and directly monetize the debt.

Debt write-downs and restructurings are deflationary while money creation and debt monetization is inflationary. Reducing debt burdens relative to income involves getting the balance between the deflationary and inflationary elements correct.

When bubbles burst and countries are forced to decrease their debt to income ratios, private sector credit growth, private sector spending, asset prices, and net worths decline. The decline is self-perpetuating as cash shortages occur, which leads to asset sales, which lead to lower creditworthiness, and so on, in a negative self-reinforcing cycle.

Governments try to help offset the funding gaps by issuing debt, such as bridge loans, and central banks creating money and providing liquidity assurances. They increasingly accept collateral of lower quality to help save the system. Fiscal deficits increase.

Central banks reduce real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) interest rates and governments spend to increase nominal GDP above nominal interest rates to prevent the debt from compounding faster than the economy can grow.

However, because of low real interest rates, poor economic conditions, and weak currencies, their debt and equity markets will struggle. Other countries emerge in their earlier stages of development that are less expensive to invest in.

With large debts, large future obligations, and often large fiscal and balance of payments deficits, countries stuck with this set of conditions want to see their currencies decline to provide relief for debtors. Their relative power and influence in the world declines as other countries come up to challenge them.

Conclusion

Countries and empires rise and fall throughout time. These cycles have occurred for thousands of years. They vary based on countries’ sizes, cultures, and other variables. For that reason, no cycle is exactly the same as another. However, the cycle of countries’ producing wealth, expanding their influence and power, increasing their debts relative to productivity, getting into problems handling their debt and obligations, and declining, has been going on as long as history has been recorded.

The fundamentals of how empires rise and fall haven’t changed. It’s a reflection of human nature.

Modern financial market structure may be different, as are monetary systems, but the process of how they work is the same. Gold used to be money and remains a reserve asset after thousands of years. Countries, nation-states, and empires would use gold and gold coins as money. Each coin was worth a certain amount. As their debts increased to the point where they couldn’t be serviced, those responsible for producing currency would reduce the gold content of each coin to create more of it.

This is not dissimilar to US President Franklin Roosevelt in March 1933 devaluing the dollar against gold and breaking the “gold clause” from debt contracts. The pricing or the amount of the commodity that could be exchanged for each unit of currency was altered to be able to create more money. Under Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6102, it effectively abolished gold ownership and forced gold to be exchanged for paper currency at $20.67 per ounce (about $415 per ounce in today’s money). This allowed more currency to flow into the economy to help resolve the country’s debt problems during the Great Depression. About one year later, gold was devalued under the Gold Reserve Act to $35 per ounce (about $700 per ounce in today’s money). Raising the dollar to gold conversion incentivized more people to exchange their gold for paper dollars. That helped debtors relative to creditors by making debts and liabilities cheaper and easier to service.

Going through this cycle in its entirety nonetheless takes a long time, often hundreds of years. As a result, the changes seem inconspicuous to most who live through them and are usually irrelevant to investors taking shorter-term approaches even though they matter a lot in terms of the big picture.

Moreover, for elected leaders whose terms are typically short and in turn operate on shorter time horizons, this progression is practically immaterial to the decisions they make.

This is also why they’re bound to occur. Politicians always feel compelled to spend even if not much care is given to how it will be paid for. In late stage developed countries that typically have significant deficits (or worsening surpluses if they still have them), high debt, and large piles of future obligations, it will not be paid for by reduced spending or increased taxes, but rather through the currency.

As a consequence, these cycles go on in a way that’s usually not governed well, making them susceptible to occur.

If countries could avoid having debt growth exceed income growth and income growth exceeding productivity growth, then economies wouldn’t get into these classic problems and these cycles more or less wouldn’t occur.