‘Trilemma’: Currency Regimes Explained

In economics, a “trilemma” describes a situation where three competing elements are present, and a solution necessitates choosing two, forsaking the third due to their mutual exclusivity.

Pursuing all three usually results in instability or inefficiency. This concept is applicable in various fields including healthcare and currency management policies.

In currency management policies, policymakers must decide between controlling capital flows, determining the exchange rate, and maintaining monetary policy autonomy, based on their specific circumstances.

This choice significantly influences currency fluctuations and the attraction of foreign investments.

Capital controls represent any measure taken by a central bank, government, or regulatory body to restrict the flow of foreign capital going in and out of the domestic economy. This can include a mix of tariffs, taxes, legislation, and volume restrictions.

They are more common in countries where capital reserves are volatile and in lower quantities. Capital controls normally scare away foreign investors and can lead to inadequate economic development.

Key Takeaways – ‘Trilemma’: Currency Regimes Explained

- The economic “trilemma” in currency management requires governments to choose two out of three strategies:

- controlling capital flows

- stabilizing the exchange rate, or

- having an independent monetary policy

- Each with its own implications and challenges.

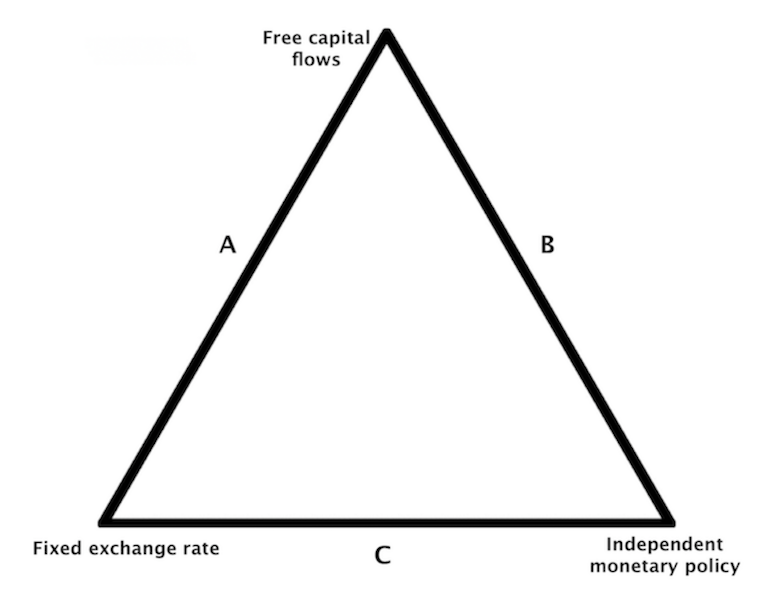

- Different countries adopt varied approaches to this trilemma, influenced by their economic conditions, historical contexts, and policy preferences, resulting in distinct currency management strategies (Side A, B, or C in the image below).

Trilemma: 1) Capital flows, 2) Exchange rate, 3) Monetary policy autonomy

When countries are faced with this particular set of policy trade-offs, they may achieve one particular side of the triangle at any particular time illustrated by the diagram below:

In managing their currency, countries face a trilemma where they can opt for one of three sides:

Side A

Side A involves fixing the exchange rate and allowing free capital flow but relinquishing independent monetary policy.

Side B

Side B allows for free capital flow and an independent monetary policy but with fluctuating exchange rates.

Side C

Side C maintains a fixed exchange rate and autonomous monetary policy by restricting capital flow.

How these strategies are influenced

These strategies might be influenced by various factors including efforts to prevent bank runs or the influence of alternative assets like gold and cryptocurrencies, which can sometimes bypass capital controls, albeit with potential legal and regulatory risks.

Restrictions on capital flows are typically done to support domestic banking systems. If a country’s banking system sees a run on its deposits, then it may face insolvency if loans cannot be called to cover deposit withdrawals.

In 2015, Greece instituted a temporary bank holiday to forestall the prospect of a bank run. Domestic bank customers were not able to execute wire transfers out of the country.

Sometimes people will try to circumvent capital controls by moving their money into alternative assets such as gold.

Accordingly, in various points throughout history, governments have banned the ownership of gold as an additional type of capital control.

Alternatively, price and wage controls may be implemented. Typically, they don’t work very effectively and create distortions rather than mitigate problems.

These days, cryptocurrencies might be one alternative, off-the-grid asset that people might use to move their money “offshore”, or at least as a way to store their wealth in a place deemed safer than their domestic currency.

Part of the risk associated with alternative digital currencies is that they may also be subject to legal and regulatory supervision or banned altogether.

If a government can’t adequately control cross-border capital flows and wants to maintain an independent monetary policy, then it must free float its currency.

These situations, when identified pre-emptively, can be big opportunities for currency traders.

Sometimes, currency peg removals will occur more or less unexpectedly and sometimes they will occur more predictably.

Examples of pre-devaluation scenarios

Is the country low on reserves? If its low on reserves, it will be much less likely to defend the peg because it will eventually run out.

Is the country’s growth suffering in combination with limited monetary policy options (e.g., rates at zero, quantitative easing less effective)? The next viable part of the toolkit is likely to be currency devaluations.

Is a country pre-paying its foreign-denominated debts? That might indicate that it’s about to devalue its currency.

Debt denominated in a foreign currency becomes more expensive when its domestic currency decreases in value, thus incentivizing paying it down before a free-float occurs.

Examples of Side A, B, and C

Let’s look at some examples of where various countries fit according to the above diagram:

Side A (Eurozone)

- Unified currency (Euro) facilitates free capital flow among member states.

- Individual countries cannot pursue independent monetary policies, which sometimes leads to economic strains during crises, as they cannot devalue their currency to spread the effects externally.

- The shared currency can cause imbalances, with some countries finding the Euro too strong or too weak for their economic conditions.

Side B (United States)

- Prefers an independent monetary policy to adjust key economic levers according to current conditions.

- Allows liberalization of its capital account, enabling free capital flows.

- The exchange rate is determined by natural market forces, providing flexibility and adaptability to economic changes.

Side C (China and Bretton Woods system initially)

- Maintains a fixed exchange rate to manage economic stability and high levels of debt.

- Controls cross-border financial flows to sustain the fixed exchange rate and independent monetary policy.

- In the case of China, the approach supports its top-down, state-directed economy.

- The Bretton Woods system, until 1971, allowed countries to set their own interest rates while pegging currencies to the US dollar, restricting or minimizing capital flows to maintain the system’s sustainability. It transitioned when the US moved to a free-floating currency, marking a shift from Side C to Side B.

Government challenges

Governments, especially central banks, need to tailor their policies according to their specific circumstances.

Developed countries like the US prefer a policy that allows for an independent monetary stance and free capital flows, adjusting to market forces naturally.

In contrast, the EU, sharing a common currency, sacrifices individual monetary policies, which can lead to economic strains, as seen in Greece’s debt crisis in 2012.

China represents another approach, maintaining a fixed exchange rate and controlling cross-border financial flows to manage its high debt levels and ensure economic stability.

Historically, the Bretton Woods system also followed this approach until the US transitioned to a free-floating currency, boosting its stock market but also leading to high inflation in the 1980s.

In the end, any currency peg that doesn’t align with the currency’s fundamentals isn’t sustainable.

Other Trilemma Applications

For example, the economics of healthcare is often conceptualized as a trilemma.

You have the competing elements of quality/reliability, universality, and affordability.

Generally speaking, pick two.

- If you want quality and affordability, it won’t be universal.

- If you want quality and universality, it won’t be affordable.

- If you want affordability and universality, it won’t be of very high quality or reliable (outside of the basics).

Various public and private solutions can act to help supplement each other.

If someone who can afford better care isn’t happy with the quality of what’s publicly available, he/she will typically look for a private plan.

Conclusion

A trilemma in currency management forces governments to choose two out of three options:

- controlling capital flows

- stabilizing the exchange rate, or

- maintaining an independent monetary policy

Governments can either peg their currency while restricting capital flows, allow a free-floated currency with open capital borders, or fix the exchange rate and limit capital flows, relinquishing independent monetary control.

The chosen strategy depends on a country’s economic conditions and the capabilities of its policymakers.