The 3 Main Forms of Monetary Policy

We are in unique times in the markets given the current limitations of where we are in the economic cycle. We are in a situation where there is limited room with traditional monetary policy tools should the economy turn down.

As covered in a different article, there are three main equilibriums that markets are always fighting for, which feeds through into asset prices. It’s important to cover these equilibriums because they work into the calculus of how policymakers make decisions, particularly central bankers who operate on the monetary side.

They predominately focus on the first equilibrium (economic capacity utilization), because some form of it is ingrained in their statutory mandate (inflation, or maximum employment or output within the context of price stability).

The second and third equilibriums are nonetheless very important as well, for policymakers, regulators, and financial market participants.

1. Economic capacity utilization can be neither too high nor too low.

Classically, the best time to buy stocks is when unemployment rates are high because there is a large output gap.

When output gaps are high, central banks need to ease monetary policy to get lending conditions favorable again. Once that’s done and nominal interest rates are pushed below nominal growth rates, equities will bottom, hiring will begin to improve sometime after (labor is a lagging indicator).

When non-supervisory workers (a bit more than 80 percent of the working population) see higher year-over-year wage gains than supervisory workers (“bosses”), this is an indication that they have higher bargaining power due to a lack of substitute workers. Accordingly, in such circumstances, the output gap is considered increasingly “closed” due to a lack of labor slack.

This follows the normal pattern. Typically, as labor scarcity increases, workers can bargain for higher wages.

The extra wage costs are often passed off by corporations as higher prices, inducing higher inflation (i.e., monetary demand in excess of product and service output).

To stamp out inflation, central banks hike interest rates. This increases debt servicing costs beyond the cash flows available, producing a downturn in the economy. When debts can’t be paid back on a certain scale, credit creation decreases, and the economy enters a recession.

The distributional effects in a continent like Europe are nonetheless quite high because of their unique monetary system. With so many countries pegged to a single currency in the euro, they aren’t able to pursue independent monetary policies.

This leads to several lagging countries, particularly on the periphery (e.g., Spain, Greece, Italy), which have trouble closing their gaps when monetary policy is perpetually left too tight relative to their existing economic circumstances.

2. Debt servicing payments must be in line or lower than income growth

Most economies in developed markets go into recession when the central bank begins tightening monetary policy to curb inflation. But toward the end of that cycle, the growth / inflation trade-off is hard to get right and the central bank usually over-tightens.

Debt servicing swamps the cash flows available, lenders become more cautious, private sector credit creation diminishes, asset prices fall, collateral availability diminishes, and the cycle is self-reinforcing until the central bank eases again.

That’s the normal dynamic. Because developed markets are highly indebted relative to their output, the current cycle is different relative to most.

Rate hikes won’t have any issue in slowing down output and inflation, not only through increased rates on new loans and floating-rate debt, but also due a contraction in the supply of loan funds.

Most spending in the economy is credit-driven. Credit (promises to pay) outweighs money (what payments are settled with) in the US economy by a factor of 19x.

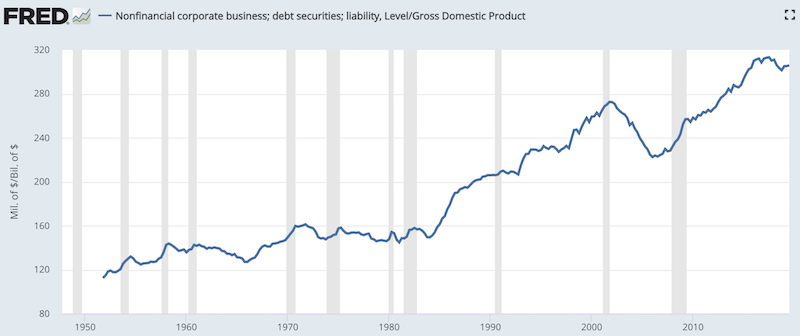

Non-financial corporate leverage relative to output is at an all-time high.

(Sources: BEA, Board of Governors)

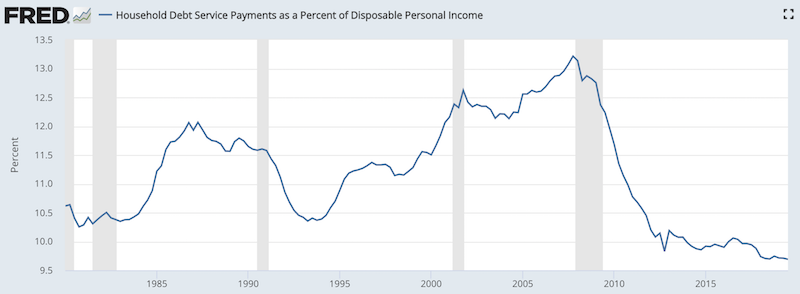

But it’s manageable because debt servicing burdens are moderate.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

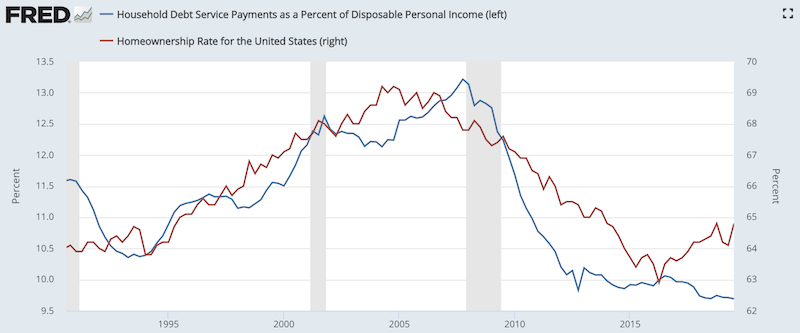

However, we still have to control for the fact that even with the decline of the homeownership rate from 69 percent in the mid-2000s to its 64.8 percent mark currently (i.e., more people rent), we still have to take into account non-debt obligations and other forms of non-discretionary spending.

Mortgage debt is a material portion of household finances, but when this is essentially converted to rent payments it can understate the true level of financial stress on households. This is because it will not show up in the debt numbers.

We can observe the effect of this in the data by comparing the above dataset to the homeownership rate on the same graph and note the tight correlation:

(Sources: Board of Governors, Census)

The correlation is +0.68 since 1980 and +0.88 since the end of the 1990-91 recession. There is causality involved in this relationship because a large amount of household debt is linked directly to housing.

Even though rent is not debt – and therefore won’t be visible in the data – rent is a non-discretionary expense and such non-debt items must be included in the calculations to accurately monitor financial stresses on the household sector.

Even so, for households, the most important part of the economy, debt servicing burdens are also on par with an early-cycle economy. In general, when economies have a lot of debt, rising rates divert a disproportionate amount of capital from consumption and investment – things that contribute to output and influence prices (i.e., inflation) – and toward debt servicing, which is disinflationary.

As a result, raising rates in this type of backdrop will have no issue slowing down the economy. The risks to tightening outweigh those related to easing or staying steady.

There’s an asymmetric risk involved. If inflation ticks up a bit, it’s not going to be a problem, so rate hikes are not necessary. Cost pressures in the economy are not an issue so far. Wage growth is on par with a mid-cycle economy; unit labor cost growth is early- to mid-cycle. Wage pressure is highest in the most skilled professions where there’s a lack of supply relative to demand.

If they do raise rates, killing off growth would be very easy to do. (See the reaction in stocks in Q4’18, as they discounted higher interest rates and lower future cash flow.)

3. Equities must yield higher than bonds, and bonds must yield higher than cash and by the appropriate risk premiums.

For the transmission mechanism of capital markets to work, the appropriate risk premiums must be maintained between and among asset classes. Sometimes these temporarily get out of whack.

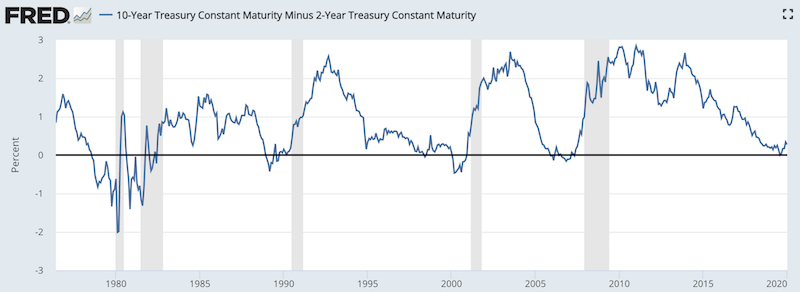

For example, the financial media often pick up on yield curve inversions, such as that between the 10-year and 2-year sovereign bond yields.

This is especially popular in the US because it’s predicted eight out of the past five recessions (i.e., three false alarms, four if you include the one from August 2019).

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

Equity yields (i.e., earnings yields) will sometimes invert with mid-duration yields or even with cash yields. The run-up to the 2000 tech crash was one such instance.

Some believe that inversions are always bad and should be avoided. But this is not necessarily true, so long as said inversions don’t persist for long periods of time.

If short-term rates were chronically left well below the returns of the longer-term rates that have duration and credit premiums, then risk-taking behavior would become excessive.

People would lose a healthy fear of risk and imprudent speculative behavior would get out of control. Financial markets are not simply mechanisms where you can speculate on whatever by borrowing as much money as possible and have it work out.

For that reason, risk premiums should neither be too high nor too low for extended periods to ensure that capital allocation remains reasonably efficient and is following sustainable patterns.

While interest rates are the primary way that influence these equilibriums, if a problem is occurring, it can be targeted directly through the central bank and their regulatory authorities with macroprudential policies. (However, central banks’ setup in these respects is still largely weak.)

The Three Main Forms of Monetary Policy

Monetary policy can be broadly categorized three different ways:

a) primary: short-term interest rates

b) secondary: longer-duration interest rates, and

c) various tertiary forms, which involve different potential spending and lending programs

Primary monetary policy

The primary form of monetary policy is driven by short-term interest rates. Everybody is familiar with this, which involves the central bank adjusting cash or deposit rates.

This type of monetary policy is preferred because it has the widest impact on the economy.

A reduction of interest rates by central banks is stimulative through the following channels:

1. It stimulates demand by lowering debt servicing commitments. This improves the amount of cash that is available for consumption and investment.

2. It encourages credit creation and demand to buy rate-sensitive items, such as housing and machinery.

3. Lowering interest rates will increase the net present values (i.e., the prices) of financial assets, holding all else equal. This creates higher wealth and more valuable collateral assets.

The issue with interest rate based monetary policy is that it ceases to be effective once these rates hit zero.

Some central banks do go below zero, such as the Swiss National Bank, which has gone to nearly minus-100bps, the Bank of Japan (minus-10bps), and the European Central Bank, which has taken its deposit rate to minus-50bps.

While making the return on cash negative makes it a little bit less attractive and can help push more people out of it, the marginal returns of taking the cash rate below zero are diminished relative to when it’s positive. Savers still want to save. Borrowers and lenders will still be cautious with each other. Bank profitability can be an issue.

The returns on other asset classes like bonds and equities also likely have very low forward returns when cash rates are negative (following the third equilibrium covered in the preceding section), which makes their returns unattractive relative to their risks.

At a certain point, investors will no longer continue to park more money into riskier assets when the risk premiums compress to unacceptably low levels.

During the 2008 financial crisis and US Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s, rates also hit zero lower-bound, which forced the central bank to move to a secondary form of monetary policy.

Secondary monetary policy

Quantitative easing (commonly abbreviated QE, and also known as asset buying or “printing money”) is the secondary form of monetary policy. It was popularized as the US recovered from the financial crisis. It began in March 2009, which represented the bottom in stocks and the beginning of the decade-plus bull market run.

While interest rate driven policy primarily affects the creditor / lender relationship, asset buying most heavily impacts investors and savers.

QE mostly involves buying debt assets, mostly at the sovereign level and other government-backed securities. (Though due to the situations in Europe and Japan, both have also ventured into corporate credit and, in the case of the latter, equities through exchange-traded funds (ETFs)).

When a central bank buys a financial asset, it puts cash into the private sector.

Namely, it creates the cash – because it has that authority – and buys a bond. The central bank puts the bond on its balance sheet and the cash goes to the investor. In the investor’s case, they typically want to buy something of a characteristic that was most like what they already owned.

But what the investor does with the cash makes a big difference in how effective the program is.

If they buy financial assets that help finance spending – the assets go up and those who invested in them have a high propensity to spend this money – that is stimulative to the economy.

When they don’t, then it typically leads to gains in financial markets but not much in the way of spending that actually gets into the real economy.

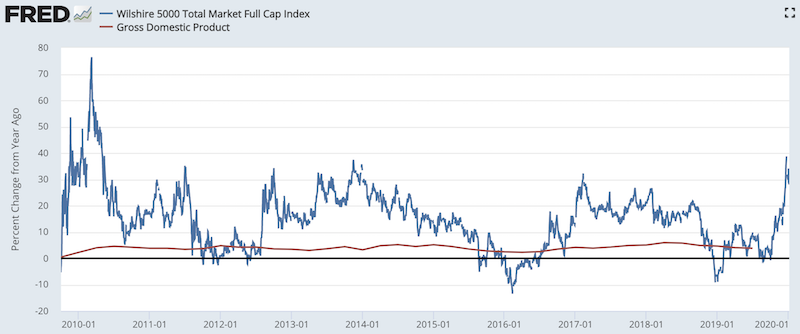

In the diagram below, we can view the year-over-year change in stocks (blue line, representing the Wilshire 5000 index) against the year-over-year nominal growth in US GDP (red line). Financial assets have greatly outperformed the broader economy.

Because asset buying policy tends to benefit investors and those who own financial assets, and doesn’t provide a ton of benefit to those with don’t own financial assets, wealth gaps tend to appear. This can increase social frictions and bleed into political movements, particularly those of a populist bent with policies that increasingly polarize both the left and right end of the spectrum.

Asset buying is typically not as effective as changing interest rates. Where it does tend to have the most effect is when liquidity and risk premiums are large. When those premiums are high, the ability to boost asset prices is highest and causes those premiums to decrease.

Because there is more money available to invest, it inevitably goes into assets of all varieties and progressively increases the purchases of riskier assets that provide higher expected returns. This creates a type of wealth effect.

However, the use of asset buying to stimulate the economy becomes less and less effective the more it’s used. Risk premiums fall and asset prices rise to such high levels that their forward returns relative to their risks become poor.

The poor risk-adjusted compensation makes it difficult to bid up prices further. Even if central banks try to stimulate further – like with where the BOJ is with their asset buying program – the wealth effect diminishes.

Some investors may even go back to choosing cash when the yields on bonds, equities, and other higher-risk assets look undesirable, even when the central bank is trying to make cash look unattractive.

When asset buying is more or less exhausted, this will show up through weak (below expectation) private sector credit creation.

When this occurs, central bankers could try to compensate for poor effectiveness by trying to buy even more assets. While this can help, the effectiveness will be low so long as credit and liquidity premiums are low.

Moreover, the persistent “printing” of money can lead to a depreciation of the currency to the point where people begin to question its value as a store of wealth and value. This can push more money into alternative stores of wealth like gold.

Typically, when economies are at this stage, there are a lot of financial assets (or claims on future purchasing power) relative to the ability to satisfy those claims. This is what leads to the decision to print a lot of money in the first place.

But the deprecated value of the currency, as is often the case, can lead to more fundamental problems about the monetary system as a whole. The fear of this is more common in emerging markets where people are less likely to assume that their domestic currency will always be sound.

Nonetheless, currency regimes tend to work well for decades or even centuries at a time. Accordingly, the inflection points in currency regimes tend to be reached infrequently. At the least, they tend to be much less common than the standard business cycle that we’ve become accustomed to experiencing during our lifetimes.

But that risk is always there, even if it’s under-emphasized because we rarely (or never) experience it.

When you put your money into any financial asset, you believe that you can later convert that into purchasing power to obtain goods and services (or buy other financial assets, though consumption is ultimate end-product or purpose).

When workers provide their time and skills to contribute to the production of goods and services, they expect to be compensated in currency, which can then be used to purchase goods or services (or savings and/or the purchase of financial assets).

However, because financial assets – i.e., debt, money, currency – can be created much more easily than product and service outputs, the amount of financial assets in circulation tends to be much higher. So, claims on goods and services often run in excess of their intrinsic values. Eventually, such claims have to be devalued (i.e., monetized) or have to be restructured.

Central bankers generally prefer monetization measures (QE, asset buying) over restructurings because they are stimulative.

On the other hand, debt restructurings and write-offs are contractionary given purchasing power is either deferred to the future if their maturities are lengthened (investors / savers have to wait longer to access it) or see the purchasing power they believed that they had through the “asset” disappear altogether.

The issue with monetization measures is that one obligation is simply exchanged for another. The central bank creates money and exchanges it for debt.

So long as the central bank has the authority to keep doing this, and the currency remains trusted as a viable store of wealth and medium of exchange, this process can continue.

And it’s easier to continue in reserve currency countries than it is in jurisdictions where the currency’s viability is not taken for granted. But it’s the same type of structure as a pyramid scheme.

If there is not a sufficient enough amount of goods and services produced to make the obligations worth what they are, monetization measures simply delay the inevitable (i.e., devaluations, restructurings).

Moreover, monetization doesn’t help it getting at what matters most over the long-run in terms of the economy, which is productivity. This is the force by which living standards are improved as we learn more, invent more, create new and better products and services, and become more efficient.

Productivity is nevertheless not volatile enough that it means much in the short-term for financial asset prices. Instead, the prices of financial assets are more influenced by the creation and contraction of credit.

Primary and secondary monetary policy wrapped together

In the main three reserve currency countries/jurisdictions – i.e., the US, EU, and Japan – we are toward the latter stages of the effectiveness in both primary and secondary monetary policies.

Rates are at zero or negative in the EU and Japan. They are only slightly positive in the US.

Likewise, in the EU and Japan, bond yields across the curve are very low, which also feeds through into equities, real estate, private equity, and other types of asset classes.

So, asset buying has reduced effectiveness. The US has more room than the EU and Japan, but it will also soon be similarly tapped out.

For example, the US yield curve as of the latter part of 2021 had 0-200bps of room, ranging from the cash rate to the 30-year Treasury bond.

If you take the effective duration of stocks, which is about 25 (i.e., how many years, based on the current earnings yield, would it take you to make the equivalent of your principal back in terms of the expected cash flows produced?), and multiply by the yield left as a percentage – assuming perfect feed through into reducing corporate financing costs – you can get at the amount that central banks can squeeze out of the equity markets. For example, if the central bank reduced financing costs across the curve by about one percent (100bps), that’s another 25 percent out of stocks.

After that point, the US will be in a very similar scenario to the EU and Japan.

In this case, when monetary policy in both of the standard forms is maxed out, central bankers must turn to a tertiary form of monetary policy.

Tertiary forms of monetary policy

When rates are exhausted at the zero-bound (or effective lower-bound) and asset buying has largely run its course, then central bankers have a new problem to confront.

Despite their comforts with using these policies, their effects have diminished and they contribute less to increased spending in the economy.

Private sector credit creation lags and the economy enters into a period of low growth. Also, because risk and liquidity premiums have become so compressed due to the effects from previous policy actions, forward returns on assets are low. Investors, as a consequence, are less willing to bid them up further.

Because of the limited ability to stimulate the economy or asset prices, central bankers must turn to tertiary forms of monetary policy.

This can take various forms, but at this stage, money and credit programs will go increasingly to support spenders. It must also incentivize the recipients to spend it otherwise it risks hoarding.

In the US, these choices were last faced in the 1930s during the Great Depression (and increasingly now).

The greatest risk when primary and secondary policies are exhausted is that central banks will overuse monetization measures and currency devaluations. This can eventually cause inflation without bringing back growth to a point where stimulatory measures can eventually be eased back. Currency devaluations are also zero-sum in nature, as one currency’s gain is another’s loss.

Tertiary monetary policy forms work by working around the interest rate and bond markets as transmission mechanisms. They are effectively constraining forces. When rates and asset buying are maxed out, they cease to be effective relative to what they once were.

In other words, spending doesn’t have to go hand in hand with borrowing.

This can mean, but is not limited to, greater coordination between fiscal and monetary policy.

In these cases, the central bank isn’t merely transmitting its policy through the banking system and bond market but rather by directly assisting spending and consumption programs that are traditionally solely within the purview of fiscal policy.

This can take several different forms, including, but not limited to:

a) debt monetization (central bank essentially funding fiscal deficits directly)

b) helicopter money (central bank adopts the power to engage in fiscal policy)

c) capping the cost of capital (similar to what the Fed did around the time of WWII)

d) commercial bank nationalization

We will focus more on the former two as opposed to the latter two. Cost of capital pegging is similar in effect to interest rate adjustment and asset buying. Commercial bank nationalization is not essential and they are already heavily regulated entities.

Depending on the type of policy and the laws governing what they can do, they can put money directly in the hands of spenders. Moreover, they must incentivize them to spend it by, for example, having it disappear after a certain period.

For helicopter money, they would either need to change the laws or the federal government could devise a scheme where it could create non-transferable, non-redeemable, zero-coupon bonds and deposit them at the Fed and work around the laws that way.

A weakness of secondary monetary policy (asset buying), is that those who predominantly benefit from the program (asset owners, or those who have more wealth), have less incentive to spend the extra wealth they generate than poorer people.

When asset buying ceases to be effective, it will come at a point where the wealth gap is large and the economy remains weak. Accordingly, targeting spending programs at those who have less wealth will be more productive.

The amount of coordination between fiscal policymakers and monetary policymakers runs on a spectrum. Helicopter money that exists in the form of sending cash to citizens directly does not require coordination with fiscal policymakers. On the other end, providing stimulus through direct government spending or by changing incentives to get people to spend requires a more coordinated approach between the two.

Macroprudential policies, which are within the purview of central banks and their regulatory authorities, can also influence incentives.

Types of debt monetization

Debt monetization and fiscal spending can take various different forms:

New fiscal spending bought directly by the central bank

In this process, fiscal spending is increased while the central bank buys it directly. This is what the US did during World War II and also after the 2008 financial crisis.

New fiscal spending with the central bank not buying it directly

In this case, fiscal spending is increased, but the central bank will, instead of buying the issuance directly, either (i) print the money to fund it or (ii) lend to other entities outside the government (e.g., to development banks, which are part of the financing fabric in China).

Central bank prints the money and gives it directly to the government

In this case, there is no debt issuance. Instead the central bank or monetary authority prints money and the government uses it to fund its fiscal spending.

The historical examples under this paradigm are numerous – the US revolution in the 1780s, the US civil war in the 1860s, the UK during World War I, and Germany in the 1930s.

Currency debasement

Currency debasement is a sub-category of the above, where a central bank or monetary authority will instead debase a hard-backed currency.

Throughout history, currency backing has usually been with gold (and, to a lesser extent, silver) because it’s not subject to large swings in supply and demand, though it’s by no means perfect.

However, because the constraints to money and credit creation under a hard-backed or commodity-based currency system eventually become onerous, the peg is inevitably eventually broken.

Historically, this occurred in Ancient Rome, Imperial China, and 1500s England.

Helicopter money

Helicopter money is the process of printing money and directing cash transfers to individuals and households.

The term was first brought into the economic lexicon by Milton Friedman as a metaphor of cash being dropped out of the sky as a means of fighting deflation. It was referenced again by Ben Bernanke in a 2002 speech. (Bernanke went on to become chairman of the US Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014.)

To be effective in stimulating economic activity, helicopter money must:

a) target those who are most likely to spend it (those who earn less have a higher propensity to spend than those who are wealthier), and

b) be tied to incentives to spend it.

How the money is distributed could either be equitable, as in everybody getting the same amount, similar to the concept of universal basic income, but from the central bank rather than as a fiscal policy. Or it could be means-tested or aimed to be given to one group over another, following point A above.

Funds could be directed to bank accounts and matched to an incentive to spend it (such as having it expire if not spent after a set amount of time).

Or such funds could be directed at certain types of investment accounts, such as retirement funds or toward those in which it’s believed the money would be most productively used (i.e., for small businesses or entities most involved in job creation and improving economic output), or to achieve certain social goals (e.g., “green” initiatives).

The returns achieved through asset buying, such as bond coupon interest, could also be sent to households rather than keeping the proceeds with the government.

Helicopter money, in some form, has been used in Imperial China and also through such programs like the military veteran bonuses in the US during the 1930s.

Debt and asset write-downs

This is typically the least desired because it is inherently contractionary.

It relieves debt, but one person’s debt is another person’s asset. It will benefit debtors, but future spending power relied on by large segments of the population will be reduced or wiped out.

And because collateral values decrease, creditors will tend to be even more cautious lending, leading to a self-reinforcing cycle.

Governments will typically counteract this through money creation at some point. However, it is through the standard process of swapping one IOU (debt) for another (new money) as covered earlier.

Large-scale debt and asset write-down examples include Ancient Rome, the US during the Great Depression, and the 2008-11 financial crisis in Iceland.

What forms of tertiary monetary policy are best?

The idea of this article isn’t necessarily to opine on which form of policy is best, as all situations are different and have different legal, regulatory, cultural, and political hurdles to their implementation.

Different policies will also tend to fall into more than one bucket and cannot be cleanly classified into one. During the US Great Depression, there was some type of direct transfer payments paired with large asset and debt write-downs.

For example, if the government provides direct transfer payments without the central bank underwriting the loan for it, that is a form of helicopter money, but only through fiscal policy alone.

If the government lowers taxes to provide a boost the economy, it’s probably not helicopter money, though if the central bank lends the government the money to pay for the revenue shortfall, it’s a form of it.

But, in general, policies that ensure that the money will both be available and spent are most likely to be effective.

This typically means that both monetary and fiscal approaches should be coordinated. If monetary authorities deem that the economy could use stimulus while fiscal authorities are trying to run a tighter policy (less spending and/or more vying for more tax uptake), then they risk offsetting each other or being ineffectual.

For example, if the government goes toward issuing direct transfer payments (i.e., helicopter money), but there is no incentive to spend the money, then the result is likely to be suboptimal.

Nonetheless, because central banks are independent from the fiscal side to reduce interference from short-term political incentives, coordinating the fiscal and monetary side is difficult.

It is usually up to each side to recognize what is the right thing to do independently and coordinate in a de facto sense.

It is also useful when central banks can not only influence the supply and prices of credit, but can target where they want – and don’t want – stimulus to flow to.

If parts of the economy are overly indebted but other parts of the economy are healthy, macroprudential policies can differentiate between different entities and more directly target parts of the economy to stimulate.

Is this dynamic in the US, Europe, and Japan permanent?

We are in a unique conundrum in developed markets because we are relatively late in the business cycle (growth / inflation trade-off dynamic) and approaching rates that are already at, near, or below zero percent.

The question might become – are we stuck in this permanently? How do we get out of it?

Eventually the system will normalize, but it takes a while.

For some societies, because they’ve printed so much money (e.g., 1920s Germany), they need to start all over again with a new currency. It often needs to be backed by gold or a commodity, or by adopting a more stable reserve currency.

For example, Ecuador adopted the US dollar as its official currency in 2000 in response to its frequent monetary problems. 1920s Germany also began quoting local prices in US dollars once its currency effectively became worthless.

Currency regimes have oscillated between hard and fiat backings over and over again throughout history.

Recoveries in economic activity tend to be slow and often take more than five years to reach their previous peak. For countries who couldn’t manage their currency to reach a softer landing, it can take decades (e.g., 2012 Greece).

Stock prices will typically remain low and can take many years to reach their former highs depending on the circumstances related to the former market top (i.e., whether it topped within the context of a speculative bubble or a more normal price environment) and how long it takes for risk-taking behavior to make a comeback for investors who had previously been burned.

Because equity markets are at or near high points in many parts of the world currently, investors are more comfortable taking risk.

However, after a major blow-up or after a crisis, investors are more cautious even though risk premiums are high and therefore a more attractive investment, assuming the underlying monetary and financial system is fundamentally sound.

What region is in the biggest quagmire?

The EU is likely to be hit more than any other developed market economy in the next downturn. They don’t have unity within countries or between countries. Too many economies are tied together via a single currency that doesn’t allow them to pursue independent monetary policies. This leads to unequal growth outcomes and more social conflict.

They don’t have a common fiscal policy. The fiscal rules are a constraint and not always respected by individual governments, though countries like Italy are still apprehensive of what kind of ramifications will come their way if they do violate them.

Germany is the largest economy in the EU bloc and therefore has outsized influence on euro area policy.

Culturally, and because of previous circumstances, Germany is very savings oriented and generally dislikes debt and inflation. Even though debt is a tool that can be wielded well when properly utilized, many Germans fear any type of debt.

This constraint from Germany bleeds over into broader euro area fiscal policy. Accordingly, even though euro area growth is low and projects to be low for a long time, it will likely take a much more impactful slowdown to get the type of stimulative fiscal policy that they need.

With that said, not all policymakers in Germany share that mindset and other perspectives help inform euro area fiscal policy. After all, rates in Europe are zero to negative.

Many of the most creditworthy nations in Europe are at, below, or near zero percent yields through 10-year credit durations (Germany, France, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Ireland, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland).

The European Central Bank has done asset buying in terms of government debt and also into corporate debt. They’ve done LTROs designed to help eliminate a flaw within the euro system where countries don’t have autonomous monetary policies due to their linkage through the euro currency. Now, they’re doing tiered policy rates.

“Green investment” – or investment geared toward environmental and sustainability measures – is also more popular in Europe than it is in the US. Support for green initiatives is gaining steam in Germany.

Though Germans are more conscious of debt as a whole, the idea of financing climate initiatives through debt is receiving support as more “green” politicians exert influence within the country’s ruling coalitions.

The case of Japan

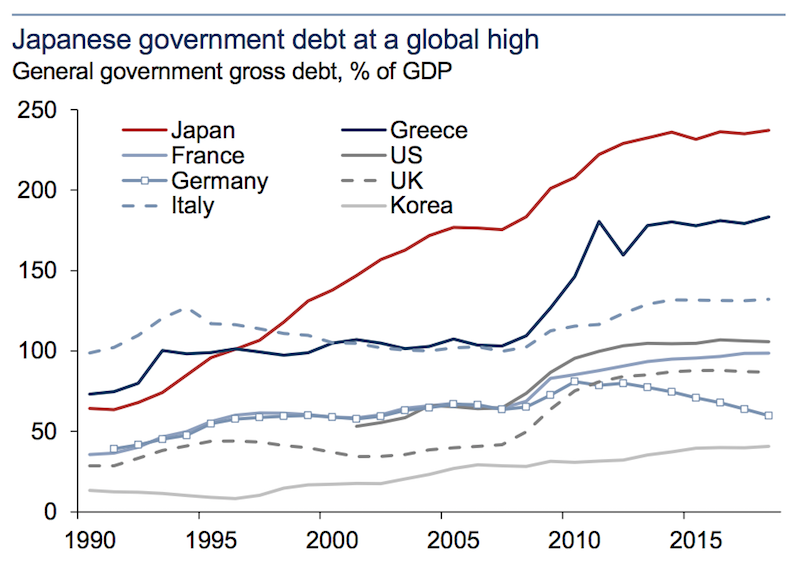

Japan has used aggressive fiscal and monetary policies for nearly three decades following the pop in its property and stock market bubble three decades ago. Their fiscal deficits have swelled to more than 250 percent of GDP, which requires perpetually low interest rates.

(Source: IMF, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research)

The potential growth rate in Japan is low (about 0.5 to 1.0 percent in real terms). This is a function of its demographics (as opposed to ineffective policy), with an average age near 50 and low birth rates. GDP growth is a mechanical function of productivity growth and growth in the number of hours worked.

If the number of workers available shrink and productivity growth doesn’t compensate for the shortfall, then recession can actually be a norm for an economy. This doesn’t mean that Japan itself will be in bad shape, but its financial market returns will be uninspiring.

And metrics evaluating the health of the economy are likely to increasingly go toward looking less at aggregate measures like GDP and annualized output growth, and more at the unit of the individual, such as GDP per capita.

What about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)?

First, there is nothing particularly “modern” about so-called Modern Monetary Theory. MMT is a new name that references a very old idea and practice – governments monetizing debt, which has been addressed within this article.

It’s the notion that government spending is not revenue- or fiscally-constrained but only inflation-constrained. Put another way, the notion that if the government owes money, it can simply create the money to relieve the burden until the point where price inflation becomes too onerous or the depreciation rate in the currency becomes unacceptable.

As noted, historically this has all happened before going back to the earliest monetized economies (e.g., Ancient Rome). It seems like a novel situation because it hasn’t happened in our lifetimes or in our society.

But these things happen over and over again throughout history. This is why, for economists and market practitioners interested in the “big picture” and why economies and markets work in the way that they do, it is useful to understand them.

If you trade different countries and different markets it’s inevitable that you’ll confront them over the course of your career.

Inflation is generally not a problem in countries where policymakers are simply negating the deflationary effects of the debt service with the inflationary effects of money creation. Done well, one will offset the other and the output to debt ratio will improve.

Broadly speaking, when nominal growth rates are above nominal interest rates, the economy will grow faster than the debt servicing requirements. Of course, this is a good thing.

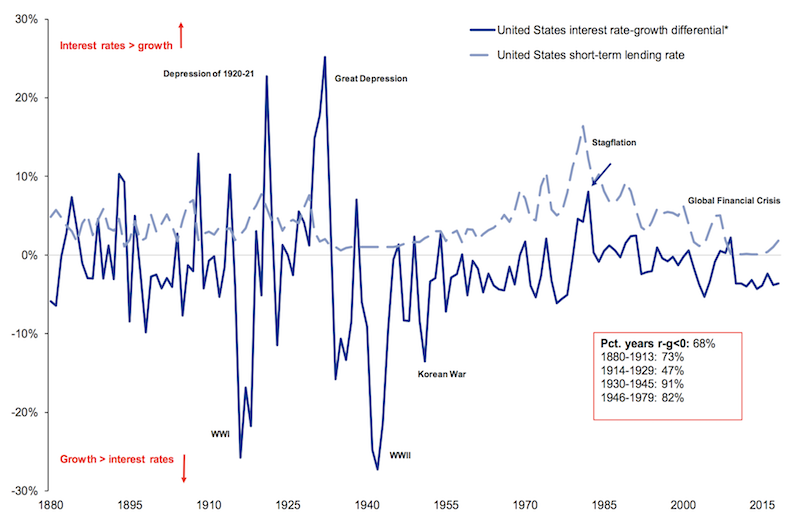

We have not had a recession since the financial crisis in the US because nominal interest rates have been kept below nominal growth rates. The diagram below shows a history of the nominal growth and nominal interest rate differential.

In situations where the debts are denominated heavily in a foreign currency and income is earned in domestic currency, then policymakers have much more limited control.

If a holder of a currency or debt asset sees the asset lose value at a rate that is greater than the interest rate being paid on it, they will lose money. If it’s expected that this weakness will continue and they will not be compensated with higher rates to offset the price depreciation, the currency will weaken.

This can lead to a dangerous situation where foreign denominated debt progressively becomes more expensive to service. This leads to more printing of money, leading to more depreciation, causing the foreign exchange debt to become even more expensive, feeding the loop in a self-propagating way.

If this type of dynamic emerges, then a country is likely to seek help from the IMF through low-interest loans or will need to figure out an alternative way to get out of their situation (such as a debt defaults and/or large write-downs and a subsequent long period of austerity).

The context of the spending

In all of these cases of new fiscal spending, it’s of course important to note that whether this spending is productive depends on what it is spent on.

For instance, we are regularly told that spending on infrastructure is always very productive. But it also depends on the country and the context. In a country like the US, infrastructure spending will likely be more productive than it would be in a country like France, which has already invested heavily in its infrastructure.

Moreover, there are first- and second-order effects of spending. Namely, even if the mathematics of a public investing project don’t work out as intended, that doesn’t mean that the project absolutely shouldn’t be pursued altogether.

For example, let’s say you build a highway linking two major metropolitan areas for $5 billion and the increased productivity that comes out of the project helps generate more tax revenue over its life.

But let’s say the economics of the project turn out to be much worse than policymakers expected and 40 percent of the debt needs to be written down. Assume that the highway has a useful life of 20 years.

Put another way – is the highway worth an extra $2 billion (the amount of debt that needs to be written down) relative to what was initially budgeted spread out over its life?

Over 20 years, this is equal to $100 million per year, or 2 percent more per year ($100 million divided by the initial $5 billion). Framed this way, you might believe that having the highway would still be better than not having the highway at all.

Of course, the bad debt loss on the project is still substantial. But it can be spread out if something closer to a worst-case scenario on the financials comes to fruition.

If, for example, 25 percent of all fiscal spending in an economy is bad with an average loss of 40 percent, this means the bad debt losses come to 10 percent of overall debt (i.e., multiplying 25 percent and 40 percent).

If total debt is equal to 250 percent of GDP assuming a 4 percent nominal growth rate, the bad debt amount is equal to 25 percent of GDP.

This is a lot, no question. But if it’s spread out over 25 years through a combination of fiscal and monetary policy, that’s one percent per year, which makes the problem much more palatable to endure.

So the second-order effects of anything always have to be considered.

If such debt comes due in big chunks or all at once, particularly in entities that have limits to how they can control their debt problems (such as private sector financial institutions), the costs would be very difficult to manage and lead to big disruptions in economic health (e.g., high unemployment, bankruptcies) and financial markets.

A lot of debt coming due all at once was the general dynamic of the Great Depression that began in 1929 and US housing bust in 2008.

Policymakers having the power to recognize these problems as they come along will depend on their know-how and authority to influence how borrowers and lenders are with each other, and whether the debt is denominated in the domestic currency.

If debts are in local currency, or the currency in which their incomes are derived, such problems can be rectified in all the usual ways by changing the rates, changing the maturities, and/or changing whose balance sheet it’s on.