Social Conflict, Revolutions, The Media, Populism, and Markets

In US cities and other parts of the world, a series of protests, riots, and social conflict have broken out over the murder of George Floyd.

Unrest over racial tensions and/or police brutality – followed by attempts to restore order – is a pattern that’s occurred many times historically.

Within the past 50 years or so, there’s been the 1968 riots across the US after civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, the 1992 Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, the 2014 Ferguson unrest, and the 2015 Freddie Gray riots, to name a few of the most notable examples.

These tensions periodically flare up for a time. Lots of influential people, including celebrities, sports stars, politicians, and notable individuals in many companies, come out to make noble sounding, politically correct statements about their outrage and sympathy, and the issues slip from national focus.

Right now, we’re in a particularly vulnerable period, as all the basic raw ingredients are there for social conflict and other civil disruption. People were already at each other’s throats (e.g., the left vs. the right, capitalists vs. socialists) when economic conditions were good.

Add a bad downturn into the mix that’s much worse overall than the last crisis in terms of depth and dispersion across sectors, and the whole thing becomes amplified.

The set of conditions we have today in developed markets are most analogous to the 1930s period.

– Economic downturn; high debt to income ratios exacerbated the drop with the lack of central bank tools to rectify the situation

– Very large difference in the economic conditions of various parts of society

– Not only a wealth gap, but a values gap

– Opportunity gap – for example, the top 20 percent of income earners spend approximately 4x more on their children’s education than the bottom 80 percent

– High political and ideological polarity, which intensifies infighting and lack of cooperation between the two sides

You take that mix historically, which we have today, you often see large social tensions and/or revolutions in one form or another. This makes most everyone worse off and threatens the cohesive fabric of the country.

1930s: An analogous period

In the 1930s, there was a similar period when there was a downturn, large wealth gaps, political populism, and limited ability for monetary policies to repair the imbalances.

Four major democracies (Japan, Italy, Spain, and Germany) abandoned those systems because the fighting got so bad. Trust in the system’s ability to provide people what they needed broke down. This led to anarchy and the turning to more autocratic leaders to take control of the situation and restore order.

For example, in 1933, at the depth of the Great Depression, Hitler came to power as a bold figure who was looked at as someone who could come in and take control of a bad set of circumstances. Italy and Spain had their own bold, populist leaders in Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco, respectively. Japan’s Hirohito oversaw Japan’s militarization and imperial expansion throughout the 1930s and led Japan’s entry into World War II.

The Russian revolution of 1918 came about due to a period of economic decline following the war, large wealth gaps (e.g., 1.5 percent of the population owned one-quarter of the land), widespread discontent over working conditions (e.g., in 1914, 40 percent of the population worked in a factory of more than 1,000 employees, compared to just 18 percent in the same year in the US). There was widespread discontent with the monarchy. Socialists had widespread allegiance over the lower classes and increasingly the urban middle class. Wide ideological gaps between the ruling monarchy and Provisional Government created division. Workers’ militias, paramilitary wings, and “secret police” were established to advance the revolution.

During economically stressful periods, a lot of underlying tensions bubble up to the surface. People cave to the visceral impulse to vilify and dehumanize certain types of people they’re against, whether based on ideological leanings, race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, socioeconomic status, their vocation, and so on.

If economic conditions get worse

The compulsion for people to demonize others will intensify if economic conditions get worse. When the causes people are behind are more important than the systems they have for resolving their disagreements, the systems are in jeopardy.

Revolutions come about when people want to bring about changes that wouldn’t otherwise occur within existing systems. Those changes can come about relatively peacefully and productively, or they can come about violently and counterproductively.

The role of the media

The media’s ostensible role in all this is to inform the public. But generally, they often make matters worse with the way they sensationalize, report events in a biased way, choose sides in the fights, and push opinions that resonate with their audience to vilify the other side or groups of people they’re against.

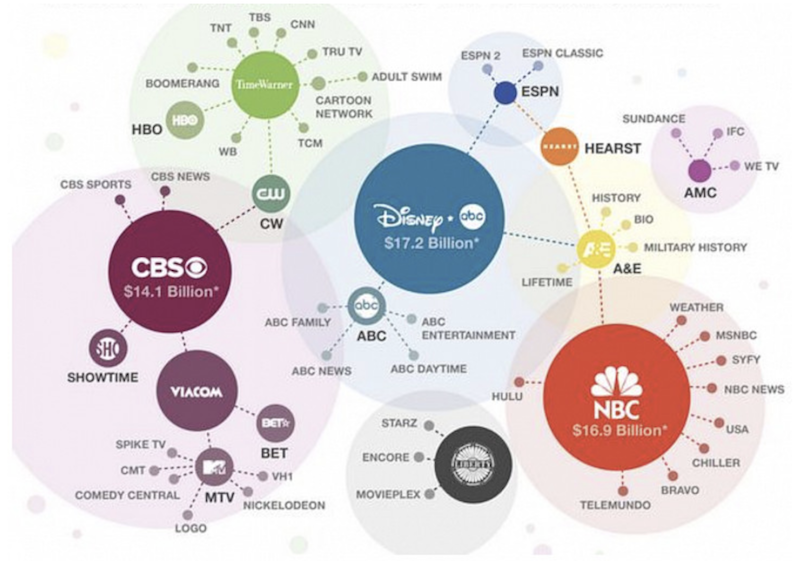

The lion’s share of the media in the US (and other countries) is controlled by a very small number of individuals, including news networks, newspapers, social media, and search engines.

In reality, the principal objective of the news media is not to inform. It’s a conduit for delivering advertising. TV programs do this by providing entertainment; news outlets do so by reporting and opining on emotionally-charged political events and topics. News networks learned long ago that picking a side is more commercially suitable than being “balanced” so they can tell their audience what they want to hear.

It’s a form of the classic confirmation bias. In general, people are overly focused on looking at things in a biased way through their own perspectives or the perspectives of those like them.

They pull levers so their audience sees whatever they want them to see. What is shown to their audience, how it’s expressed, and the general filter it goes through is chosen for a reason.

The networks have an entirely different set of incentives than those watching it. They have the power to decide what gets shown and influence what people think through the standard elements: half-truths, selectively omitting information, simplifying complex issues, advertising a cause, playing on emotions, targeting a desired audience, partisan attacks, and so forth.

It’s a game they control because they have the power and influence to do so. They can do it for commercial reasons, to influence the world in a way that reflects their values, among other reasons. It’s how something can become extremely important to being nearly irrelevant and scarcely covered overnight.

International riots and events

Events internationally are loosely related. China imposed a new security law on Hong Kong. The Hong Kong riots can incite Taiwan, which can create added tensions between the US and China, which can circle back to the US.

Hong Kong’s status as a financial and trade hub will impact some businesses. But Hong Kong is also relatively small, accounting for about 0.4 percent of total global GDP. Whether the major Asian financial center is in Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, or even Sydney, or what the distribution in financial activity is among them doesn’t really matter that much to markets at a high level.

What effect does civil unrest have on markets?

Typically, not much.

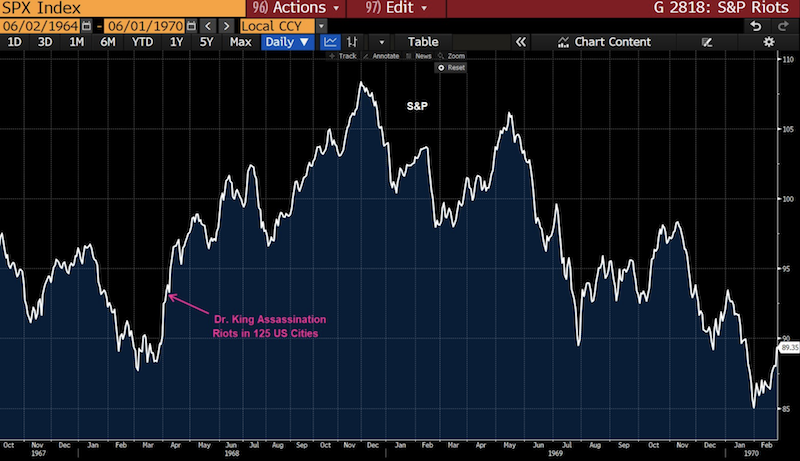

After Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, the riots that broke out didn’t affect the markets in an adverse way.

(Source: Bloomberg)

While some might think social turmoil and riots that cause large damage should logically impact the markets, they don’t usually affect them much. Some businesses have been looted and damaged, but the riot-related damages don’t affect the earnings of any given public company to a large degree.

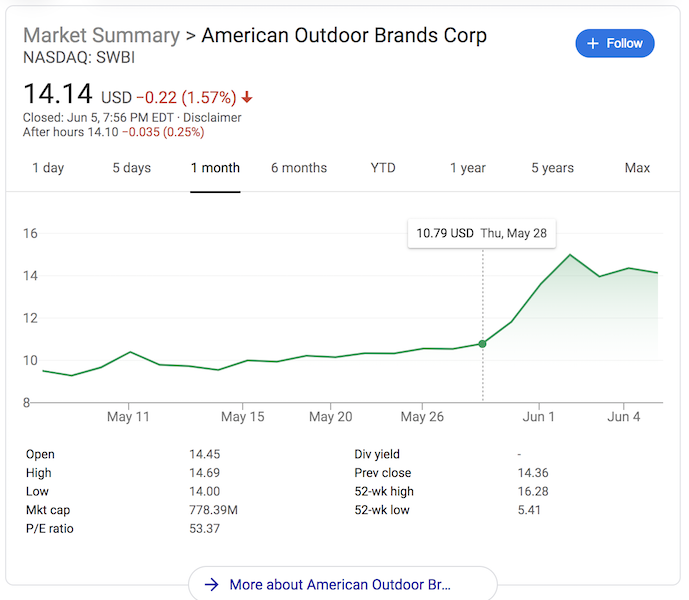

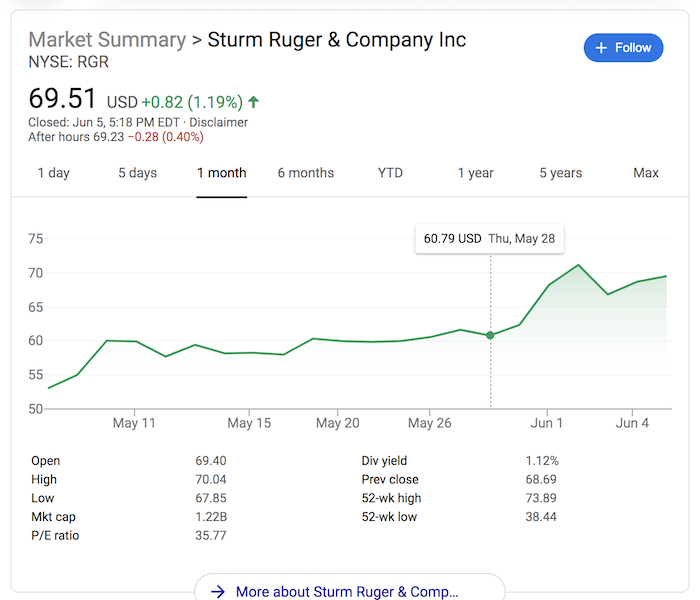

Stocks of firearm companies rose on May 28, the day large-scale riots broke out nationally. This was on expectation that violent civil disorder would encourage more civilians to purchase firearms as protection.

But on a major level, the relationship between civil disorder and the economy is nebulous.

Some might suspect that protests and rioting might make the incumbent president (Trump) less likely to win re-election. But it could also go the other way. While protesters are passionate about their causes, the looting, arson, violence, and other lawbreaking activity that accompanied some of the unrest may cause some to equivocate on their merits if they end up hurting both sides. More fighting and a tendency toward further disorder could make a “law and order” message resonate.

Ultimately, the price of a financial asset is the amount of money and credit spent divided by the quantity. With the liquidity and credit support programs of the Federal Reserve and other central banks, the rally is heavily being fed along by support from policymakers. When entities become flush with cash, it inevitably ends up going into financial assets.

The Role of Populism

The mix of conditions we discussed – wider wealth gaps, opportunity gaps, values gaps, ideological gaps – result in more political populism.

Political populism is a phenomenon that is largely not understood very well because it happens infrequently, only at about the rate of major wars or economic depressions. This is because the mix of circumstances surrounding these events or leading to them tend to also spill into political movements.

Populism is seen somewhat routinely in emerging and frontier countries – for example, in Peron’s Argentina and Chavez’s Venezuela.

However, in more stable developed markets it occurs rarely and generally only when economic or social conditions deteriorate, or the wealth or opportunity gap between different economic and/or social factions increases.

In short, populism generally comprises the following mix:

1. A platform that emphasizes “the common man”

2. Attacks the “elites” (e.g., banks, corporations) and the political “establishment”, or those in positions of power, whether corporate or political, who are perceived to be ineffective (US populist terminology includes the terms “the deep state” and “the swamp”)

3. Populism is typically characterized by:

- (i) a burgeoning gap (or a perceived gap) in economic opportunity and income and wealth inequality

- (ii) a weak or languishing economy

- (iii) social frictions

- (iv) a sclerotic political environment or an ineffective government many believe requires widespread reform

- (v) a pushback against cultural threats from those who may have different values or don’t serve the interest of the common man

Populist Policies

The movement is generally led by the rise of a charismatic and often confrontational figure who typically, but not always, runs on the following policies:

– Nationalism, or a pushback against globalization; more self-sufficiency in global affairs

– Trade protectionism

– Tighter immigration policies

– Militarism

– Stronger centralized/executive power and less democracy

– Often critical of the media

Populist Effects

Because of this blend, conflicts generally appear between opposing political groups and those who identify with distinct political brands – that is, the left and the right, with respect to both economic and social issues.

And there is generally both domestic and international conflict. Because populist figures tend to be more polarizing and hostile than diplomatic, conflicts can become forceful and self-reinforcing.

Within countries themselves, conflicts can lead to social disruption and further divides people when more individuals believe that their differences are too large to overcome and order must be restored by pushing back against the opposing faction. Of course, economic downturns only intensify them.

Populism Today

Though populism today is often characterized as a right-leaning political movement in Europe, and given Donald Trump’s election in the United States, this is not always true.

Populism can be of both a leftist and rightist character. Leftist populists will tend to embrace the elements of attacking the political establishment, calling for stronger executive powers, and condemning bankers and other parts of the corporate elite.

Historically, many populist leaders have been left-leaning, such as Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the delicate 1930s period (US), Huey Long (US), William Jennings Bryan (US), Thälmann (Germany), Lenin (Russia), Peron (Argentina), Chavez (Venezuela), Woodsworth (Canada), and Blum (France). More recently, Bernie Sanders (US) and Jeremy Corbyn (UK) have been left-leaning populists.

The election of Donald Trump represented a form of populist revolt, as his core base is mostly comprised of working class, non-coastal voters who have felt politically disregarded or marginalized by mainstream politicians on both sides of the spectrum in Washington.

The US mainstream media, which mostly operates out of the northeastern part of the country – a left-leaning stronghold – largely dismissed him as a candidate upon his declaration of running and early stages of his campaign. Even when he picked up steam, they failed to understand the popular appeal of his campaign. In office, they have provided nearly uniformly negative coverage on his administration. In turn, the media has become a targeted faction of Trump and his supporters. It’s often given its own popular moniker, “the fake news”, which has entered the mainstream (by people across the political spectrum) to concisely describe misleading or false reporting or mistruths stemming from news organizations.

Populism has also deepened its popularity in Europe by seeing some level of greater electoral success in recent years, with Marine Le Pen’s FN in France, Fortuyn’s LPF in the Netherlands, Conte’s Lega-Five Star coalition in Italy, and in the United Kingdom under Corbyn’s Labour Party and Farage’s UKIP.

Final Thoughts

Before the protests and riots, social tensions were already higher than normal. From 2009 to 2017 in the US, central banks bought financial assets to help the economic recovery from the financial crisis.

These measures were necessary to help the economy recover sooner and better overall, but increased wealth gaps. Those who owned financial assets benefited while those who didn’t own them largely didn’t participate in this wealth creation. The 11-year bull market from March 2009 to February 2020 caused the US equity market to increase in value by a factor of 5.1x.

Benefits accruing disproportionately has led to greater-than-normal fighting about what to do about “growing the pie” and how to divide it appropriately to maintain market incentives while also helping create equal opportunity.

This also gets into a question about values. This values gap creates ideological polarity and manifests into the type of political candidates that get far in the election process or get elected outright. This typically creates wider-than-average disparities between the two major political factions. In turn, this creates a great distribution of policy outcomes. This can also create more volatility in markets.

Broadly, the situation, similar to the 1930s, is like the following:

– Economic downturn

– Wealth gap

– Values gap

– Opportunity gap

– Political and ideological polarity

The uprising and social conflict occurs to varying degrees.

Back in the 1930s, this led to eventual war (beyond trade and capital) and a major disruption in who the global powers were.

History does not mean destiny, and political populism and domestic and/or international conflict does not always mean the system being revolted against will break entirely. The principles that bind us together can often be greater than those that tear us apart.

How the system will play out, what type of conflict manifests, what types of changes are made in the years ahead, and to what scale, depend on how circumstances are managed by the leaders in charge and how well established the system is.