Making Better Decisions Trading in the Markets

Making better decisions trading involves knowing how markets function and what they value. Markets are information discounting mechanisms. Where markets go is not based on what things are at face value but what transpires relative to expectations that are already built into the price.

To better illustrate this concept, let’s first consider an example.

On July 31, 2019, the US Federal Reserve cut rates for the first time in over a decade. The market, however, wasn’t impressed with Fed Chairman Jerome Powell calling the decision a “mid-cycle adjustment” and “not the start of an easing cycle”. At one point, stocks were down 2 percent, gold fell, and the dollar strengthened.

If rates are lowered, it is assumed that those particular assets should behave opposite to how they actually did. Stocks generally increase in value from lower rates based on the way discounting works through the net present value effect.

Gold goes up because of lower yields in fiat currencies, which causes wealth to flow from lower-yielding currencies and bond markets into alternative safe havens.

The dollar goes down because it yields less to those who hold it, making it a worse investment.

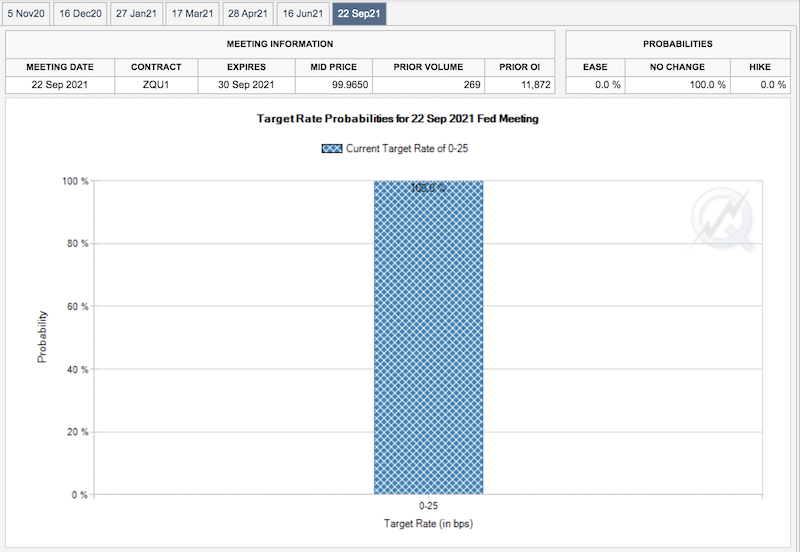

The opposite happened because going into the day, 30 basis points of easing were expected based on the dollar-weighted average opinion. The Fed cuts rates in multiples of 25’s (that is, 0.25 percent or 25 basis points). But some market participants – about 20 percent of the fed funds futures rates market – were betting on a cut of 50 basis points. On a weighted average basis, this put the expectation at around 30 basis points. When the Fed cut 25bps, the front end of the curve actually tightened 5bps.

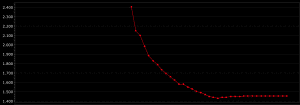

As we can see below, the general shape of the forward fed funds curve is inverted. Traders already expected the Fed to cut rates. If they cut rates, but not to the extent priced in, it will act as a tightening influence on markets, holding all else equal:

The CME Group has a tool that shows where the fed funds rate is by certain points in time:

This illustrates a primary reason why financial markets are a difficult game. To make money in the markets (outside of being long financial assets and relying on beta-related returns over time), you have to bet against the consensus and be right.

It’s not whether things turn out “good” or “bad” but rather how they turn out relative to the consensus.

For example, when a public company reports earnings and they share great progress in their business – growing revenue, expanding margins, positive earnings, increasing cash flow, new projects and initiatives – sometimes the stock will go down.

How can this happen?

While in certain cases it might be idiosyncratic market behavior (such as a large player selling), more often than not it’s because the new data that was integrated didn’t meet the expectations of the market.

And sometimes the opposite happens. A company has a negative earnings report or piece of data, but it is less negative than the market expects. This sends the stock up based on a positive re-rating in the discounted future.

Applies to central bankers as well

Central bankers, like traders, should absolutely heed attention to what’s discounted in the curve or have some sense of what the forward expectation is numerically. Their decisions have big ramifications for global markets and economies.

What financial market participants think is not just a “side opinion” but reflective of those involved in making the decisions that make the economy function. The financial system is what provides the capital (money and credit) that feeds into spending in the real economy.

The dollar-weighted average opinion of market participants is more likely to be accurate relative to a one-person / one-vote majority system dictated by a small central banking circle.

Central bankers are intelligent people, but they look at different things and weight certain data differently than “finance people”. Accordingly, they have different reaction functions.

Investors and traders think independently, need to anticipate things that haven’t happened yet, and put real money at stake with their bets.

Policymakers, on the other hand, come from environments that foster consensus, not dissent. This trains them to react to things that have already occurred, and that prepare them for negotiations, not placing bets on what is likely to happen.

Moreover, because policymakers don’t benefit from the perpetual feedback about the quality of their decisions that traders get, it’s not evident who the good and bad decision makers among them are.

Everything is a probability

You never really know anything for sure. Everything is possible. It’s the probabilities that matter. Everything needs to be weighed in terms of likelihood and prioritized accordingly.

Every decision should be viewed as a bet with a certain probability and reward for being right and a probability and penalty for being incorrect.

A “good” bet is usually one with a positive expected value associated with it. This means that the the distribution of outcomes, when estimated accurately, has a positive profit associated with it at the mean point and the “risk of ruin” is nil.

Or, in cases where the payoffs are binary or go in defined increments, there should be a positive expected outcome when the probability of being right multiplied by the reward for being right minus the probability of being wrong has a positive sign to it.

An understanding of expected value is important, as it helps to conceptualize the fact that it’s not always best to simply bet on what’s most probable. We’ll show this in the section below.

Expected value as it pertains to the danger of selling OTM options

Selling out-of-the-money (OTM) options is a good example of why.

You can sell OTM options where your odds of being right and collecting the full premium are well in excess of 90 percent.

However, if and when the price does move against you, the person making the bet can face the risk of losing many multiples of their premium or even ruin. Selling volatility is dangerous should it manifest and there’s often no limit to how much one can lose.

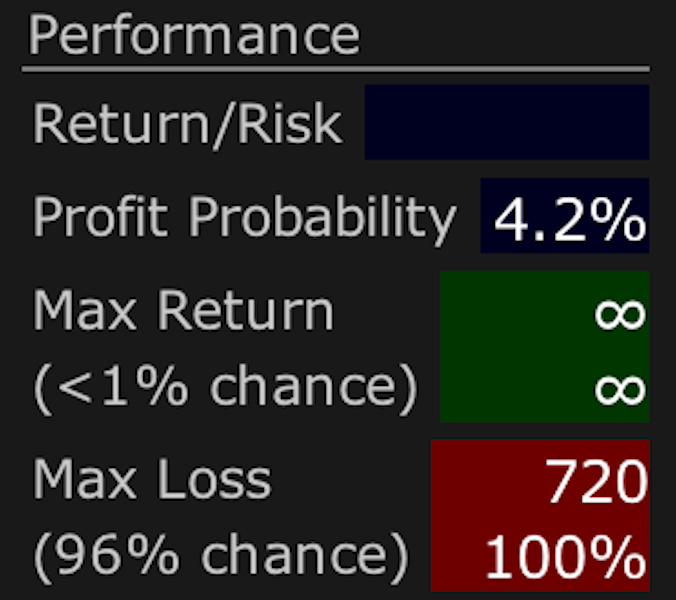

For example, if the price of Tesla (TSLA) stock is $450 and you sell an uncovered OTM call option at a strike price of 800 with one month to expiration, you can collect a premium of about $700 on one options contract based on the current pricing.

(Source: Interactive Brokers internal interface)

The odds assessment of this going ITM are estimated at only about 4 percent (though those types of probability estimations shouldn’t be taken at face value).

But if you take that number, that means if you sold this there’s about a 96 percent chance you’d right.

But Tesla is an extremely volatile stock. It can move 80 percent or more in a month. It’s done it before.

If the stock goes to $1,000, then that’s a loss of $200 per share off an 800 strike. With 100 shares per options contract, that’s a $20,000 loss for just a $720 premium, or nearly 28x the amount.

If we estimate the odds this way:

Expected value = 0.96 * $720 – 0.04 * $20,000 = -$108.80

Then it doesn’t look as favorable.

This is also why some traders like buying OTM options. If they are wrong – and they usually will be – the penalty for being wrong is relatively small.

It also entirely cuts off the left-tail risk. As long as they can cover the loss they’ll never “blow up”.

If something has a 1-in-10 chance of working out (10 percent) but the payoff for being right will be 20 times what it will cost you for being wrong, it’s probably a smart bet to make, so long as the loss of premium on the option is acceptable.

Expected value = 0.10 * $2,000 – 0.90 * $100 = $110

If you can adequately play these probabilities over and over again and spread out across many different bets (and preferably ones that are uncorrelated to each other) you will surely have winning results over enough time.

Sometimes it can be smart to take a chance even if the odds are clearly against you so long as the cost to being wrong is negligible.

Conversely, even if the odds are overwhelmingly in your favor, if the downside is terrible that means it might be smart sitting it out.

For example, even if you have a 99.9 percent chance of making $100, but there’s a 0.1 percent chance you might lose $1 million, the expected value of that decision is still $0.

Expected value also ties in with the concept of risk premium, or how much compensation traders and investor need to take a particular kind of risk.

For instance, investors have a bias to be long stocks because they intuitively know that there’s a positive risk premium associated with holding them.

The importance of raising your probability of being right

Many are inclined to make a decision if they believe their odds of being right are greater than breakeven.

However, unless there’s a time-sensitive element and a decision needs to be made under such constraints, it’s normally a good decision to try to raise your probability of being right even further irrespective of whatever your likelihood of being right already is.

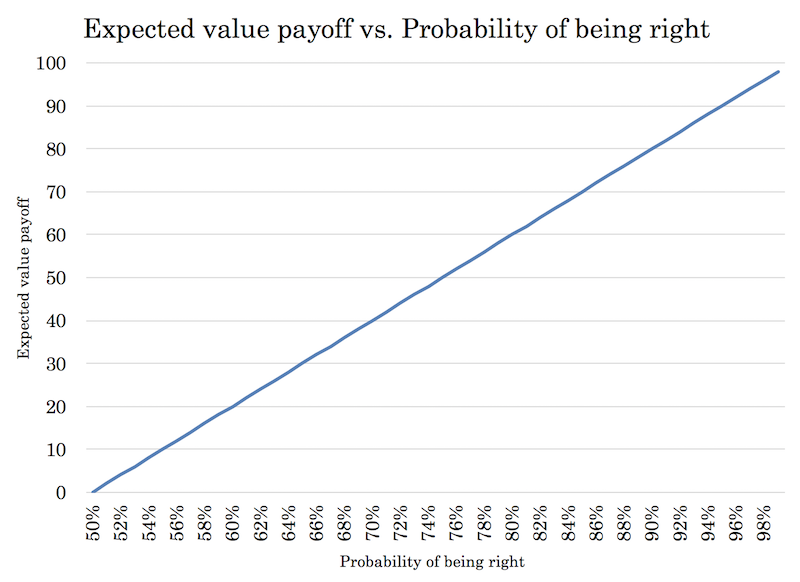

For example, if your probability of being right is 55 percent, and your expected value on each side of being right and wrong is the same, the payoff function comes to:

Expected value = 0.55 * $100 – 0.45 * $100 = $10

However, if you can raise your probability of being right by taking in more information (e.g., seeking out smart people who are fully informed and believable), you can increase your expected value calculations by even more.

If you raise your odds of being right to 80 percent, then the expected value payoff function becomes:

Expected value = 0.80 * $100 – 0.20 * $100 = $60

You increased your expected value by a factor of 6x.

Going from a 51 percent chance of being right (expected value of $2 off a $100 bet with equal reward and penalty on each side) to 90 percent (expected value of $80) is a 40x difference.

In other words, the difference between being “a little bit more likely to be right than wrong” and “likely to be right” matters a lot.

Going from 55 percent to 80 percent also means that one quarter of your bets will switch from losses to wins.

Stress testing your thinking as much as possible pays well even if you’re already more likely than not to be correct.

Finding the best thinking and answers

And the best answer as it pertains to a trade or business decision doesn’t have to be the one that only you can come up with independently.

The odds of one person coming up with the best answer is small. Even if you do have it, you can’t be sure that you do have it until it’s been stress tested.

Anyone who is seeing things with only their own perspective is going to be greatly impeded in terms of making the best decision possible. In trading and investing, you just want to make the best decisions possible to enhance your returns and reduce your risk, no matter who the best answers come from.

It’s imperative to know what you don’t know in order to understand what can go wrong. The world is very multi-faceted. So, in the trading the range of unknowns is always going to be higher than the range of knowns relative to what’s already discounted in the market.

Other applications

The same can be said for most other forms of betting, like in sports.

You have a point spread that the sportsbook implements to account for the fact that one team is generally believed to be superior to the other, which helps put roughly equal amount of money on each side.

It’s generally easy to pick what teams are going to be better, but it’s hard to convert that knowledge into winning bets because the payoffs reflect what is already known.

The process of betting will change the expected payoffs so that betting on the worse team in a game/match has about the same expected value (namely, likelihood of winning multiplied by the size of reward) as betting on the better team.

Oftentimes, the bounce of a ball or a matter of inches can flip a win into a loss for the bettor. That’s not to mention occurrences that are impossible to predict that can make a material difference on the outcome (e.g., the loss of an important player due to injury). There are a whole range of things that can’t be known relative to what’s discounted in.

Similarly in the financial markets, betting on the worst companies is as equally likely to produce profits as betting on the best ones because their relative qualities (if publicly known, of course) are already reflected in their prices. As a result, most everything is about an equally good or bad bet.

Yet many things can happen that change the outcomes over time, just as there are many things that can go wrong for the bettor putting a bet on the spread.

Knowing what isn’t known

Making the best decisions possible also means knowing when not to have an opinion and knowing who to ask the right questions toward.

Most people will give an answer if you ask them a question and not recuse themselves from answering even if they don’t know how to answer it. This type of behavior is incentivized socially because people think they’ll be perceived as weak if they don’t try to show that they have the answers.

So, it’s important to know who the best people are. It doesn’t make much sense to ask questions to those who are not fully informed.

People tend to value their own level of informedness and believability more than is normally logical. Moreover, they tend to not distinguish between who is more or less credible.

While it’s not good for “the boss” to make all decisions autocratically, it’s also not good to weight everybody’s opinions equally in a democratic way. That’s likely to lead away from the truth rather than toward it given it assumes everybody has equal ability to make decisions. Both approaches are suboptimal.

Decision making needs to be systematic where those who are more informed and credible should receive greater weight than those who don’t.

Do they have a track record of success in the thing you are trying to understand? Have they done it multiple times? Do they have a great understanding of the cause-and-effect relationships governing their conclusions?

In the markets as well as on many subjects of public interest, opinions are a dime a dozen. They’re easy to form out of thin air, so everybody has lots of them on a range of subjects even when they have no reason to believe that their opinions are good.

What’s important isn’t what people’s opinions are but rather how they came up with them. People have ideas and opinions in their heads, but they typically don’t have a process for properly examining these ideas to find out what’s true. That creates a lot of distortions.

Most do not thoughtfully and assiduously look at all the facts and perspective provided to them and reach a conclusion based on the evidence.

Instead, they make decisions on the basis of what their subconscious mind wants and filter the evidence to make it consistent with those biases. It’s a form of confirmation bias.

Some are much better at not letting their lower-level biases get in the way of suboptimal decision making than others. Some people can learn how to become conscientiously and profoundly open-minded while others can’t.

Traders will make many decisions and get clear objective feedback on them via their performance in the markets. So, they have to learn this temperament of not being inappropriately attached to their own biased perspectives and stress-testing their thinking. Otherwise they will suffer badly through lost money.

For some, they are able to do it naturally; for others it comes as a necessity, or a type of metamorphosis that accompanies a big crash. In trading, this might mean losing a lot of money (or even everything they have).

When approaching a decision, it’s important to be able to point to clear facts and evidence that fully informed and believable people wouldn’t contest. If not, the decision probably isn’t based on evidence.

Be especially wary of those who blurt out raw opinions without much in the way of exploring the reasoning governing their conclusions. Or those who will try to argue against something whenever they can find something (practically anything) wrong with it without properly weighing all the pros and cons.

The best decisions are the ones with more pros than cons, not those that don’t have any cons at all.

Markets are discounting mechanisms that take into account the dollar-weighted average opinion of all those involved in the market. Because there’s a relative level of sophistication of those who are most involved in the markets, adding value in the markets relative to a representative benchmark is not easy.

Trying to bet on what’s going to be good and bad in the markets is akin to making a bold statement that will be proven right or wrong by the results.

Most people tend to be more emotional than logical. So they tend to overreact to short-term results (same goes for other pursuits outside trading). They give up and sell low when the market is bad and buy too high when the market is good.

Sensible people stick with sound fundamentals through the ups and downs. Those who are more flighty and impulsive react emotionally to how things feel, jumping into markets when they’re good and abandoning them when they’re not.

It’s even more critical that decision making be evidence-based and logical when groups of people are working together, like for traders who work for firms or with business partners. Crowds easily become emotional and want to take control, which is not conducive to sound decision making.

Final Thoughts

Recognize that a) the biggest threat to quality decision making is adverse emotions, and b) decision making is a two-step process involving first learning and then deciding.

To make money in the markets (relative to a representative benchmark), one needs to think independently and bet against the consensus and be right. This is because the consensus view is already baked into the price of a stock, bond, currency, commodity, and everything else.

One is inevitably going to be wrong a lot doing this, so knowing how to do that well is critical to a trader’s success.

The reality of what’s true, in turn, will send you signals about how well your approach and strategies are working by rewarding or penalizing you. Accordingly, you will learn to fine-tune them through time.

Remember that you’re looking for the best answer possible, not simply the best answer that you can come up within yourself.

What’s most important isn’t knowing the future. It’s in knowing what it is you know and what you don’t know, and how to react appropriately to the information available at each point in time.

Knowing when not to bet is just as important as knowing what bets are probably worth putting on. Markets are not easy because the set of unknowns is large relative to the set of knowns relative to what’s discounted in the price. What people are blissfully unaware of and have exposure to is what typically kills them.

One can’t fall into the common trap of wishing that reality worked in a different way than it does or that your own realities were different from what they are.

If you are looking at trading a stock, you should look at what’s discounted into the future price. Across the internet, you can find forward estimates of a stock’s expected revenue and earnings per share (EPS) expectations over the next several quarters.

Even then, it’s not easy given company representatives will often release forward guidance at the same time as earnings, which will re-rate expectations of what will occur in future quarters. This is often what happens when a stock goes down despite beating revenue and earnings expectations.

After all, markets are forward looking. Whatever it’s earning right now is more or less already embedded in the price. You have to think out several quarters or years and imagine how the world might be different relative to how it is today. Earnings reports are technically backward-looking indicators (similar to GDP and inflation readings for those trading macroeconomic trends).

Making better decisions trading involves a shift in mindset from how most people view markets. Understanding what’s already priced into the market, and having an out of consensus opinion that is correct, is essential to coming out ahead in the markets over the long run.