Hong Kong’s ‘Special Status’: What It Means & How China Reacts

High-ranking members of the Trump administration have asserted that Hong Kong no longer merits a special status as it pertains to trade. This could give the semi-autonomous territory treatment similar to that reserved for mainland China.

To this point, the US has given Hong Kong favorable trading terms. This policy dates back before Hong Kong’s 1997 independence from the UK.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo informed Congress that Hong Kong’s autonomy from China is compromised. Therefore, it may increasingly be treated the same way China is treated as far as trade goes.

Hong Kong is known globally as one of the world’s most important financial centers, more or less equivalent to what New York and London do for their respective continents.

Hong Kong’s economy is broadly liberalized and has a competitive tax regime. Accordingly, it’s attracted many foreign companies to establish a presence on the Asian continent, either physically or for capital raising purposes.

Hong Kong’s location and proximity to major industrial and production centers across the China border (e.g., Shenzhen) make it an important hub for trade. $1.2 trillion worth of goods passed through Hong Kong in 2018, making it the seventh-largest trading hub globally. Traditionally, 5 to 10 percent of US exports and imports to China pass through Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s Trade Status

If the US changes Hong Kong’s special status, its trade status could be at risk.

It has special trade relations with the US by operating as a separate customs territory to mainland China, with separate tariffs and other regulations.

Moreover, Hong Kong has a free port. This is especially important because it means tariffs are not charged on the import or export of goods that flow through.

These agreements have helped Hong Kong establish itself as a global trade center. But the US subjecting Hong Kong to the same treatment as mainland China would subject its goods to additional tariffs that are not already part of those implemented by the Trump administration.

In simple terms, Hong Kong losing its special trade status would essentially put in on par with mainland China – of which the US has conflict with – and less as a traditional ally.

A new trade regime can change the cost structure of companies dependent on goods shipments. Many could decide to ship goods directly through ports in mainland China instead. Higher tariffs could mean higher prices, borne by both businesses and consumers.

Does China care about Hong Kong losing its trade status?

It matters, but not to the same extent as before.

At the time Hong Kong declared its 1997 independence, it was nearly 20 percent of China’s GDP.

However, since then, China has grown quickly and Hong Kong is now just 2.6 percent of China’s GDP. It is no longer significant with Hong Kong’s influence on growth now about 8x smaller than what it was before.

What is important is Hong Kong’s status as a global financial hub. China benefits from Hong Kong’s large financial services sector. Chinese companies seeking public offerings often want to list in Hong Kong because of its accessibility to foreign investors.

China’s banks do much of their international business from Hong Kong, mostly conducted in US dollars. With Shanghai subject to China’s capital controls, there is no clear replacement.

As of 2019, mainland Chinese banks held $8.82 trillion Hong Kong dollars (USD$1.14 trillion) in assets in the city. This amount is nearly 5x what it was at the beginning of the 2010s.

That’s only a small portion of China’s $40 trillion in total bank assets. But it’s a much larger in relation to the $2.22 trillion that China’s banks extend to borrowers outside the mainland.

The US does not directly control Hong Kong’s status as a financial hub, but Washington uses the US dollar, the world’s main reserve currency, as a source of geopolitical leverage. It has recently brought penalties against French, Korean, and Lebanese companies for engaging in business with sanctioned entities.

By saying that Hong Kong is no longer autonomous, the US would restrict the ability for Chinese banks to engage in USD-related activities and work to rein in China’s ability to operate financially overseas.

China’s mainland alternatives

Shenzhen and Shanghai have dynamic financial services sectors that serve mainland China. But given China’s economy is still heavily state-run, mainland centers have difficulty competing with Hong Kong.

Will this change?

China needs to control its capital account to fix its currency while still running an independent monetary policy. This relationship is commonly called a trilemma, where policymakers have to decide on a policy mix best suited to their situation and goals with respect to free versus controlled capital flows, independent versus non-independent monetary policy, and pegged versus non-pegged currency regime.

Without liberalizing their capital account and with a largely state-run nature to their economy, Chinese financial hubs will have difficulty being viewed as equals to Hong Kong.

How could this affect the US?

Each year, billions of dollars worth of goods and services are traded between Hong Kong and the US. In 2018, the total value of that trade was nearly $67bn according to the US Trade Representative. That figure includes $17bn worth of imports that the US bought from Hong Kong.

If Hong Kong faces the same trading terms as mainland China, US consumers will pay more for those goods. This will encourage lobbying on behalf of US businesses in the US and in Hong Kong to thwart or dilute the action. The US Chamber of Commerce has pushed back on the idea.

Purportedly, Secretary Pompeo’s threat appears to be about Beijing’s new security law for the territory and recent developments in Hong Kong. But the main logic really has to do with US-China relations, which are increasingly strained for a variety of reasons.

It goes beyond basic trade balances and toward more endemic geopolitical issues such as market competition, military power, market access, cybersecurity, property rights, intellectual property, among others.

The dispute is heavily over where and how each country will compete. This is why matters involving whether having separate supply lines is necessary.

Will there be technological decoupling where neither country cooperates on building and using each other’s technology?

This could include distinct, bimodal developments in, for instance, 5G cellular networks, artificial intelligence chips, information and data management, and quantum computing.

China’s government is heavily involved in helping companies that have the most strategic importance to the country as a whole.

This means more state support toward newer digital technologies that propel society forward and less toward the indebted “old economy” sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing. The export model grew their incomes, but taking the next step into a top global superpower, or the top superpower, will involve another type of focus.

Accordingly, China is shifting away from an export-based model toward one more focused on domestic consumption and development of these leading technologies.

Naturally, the country that is the most technologically developed tends to be the more advanced in most other ways as well, both economically and militarily.

It also branches into capital – e.g., the US relies heavily on China to help fund its deficits and keep borrowing costs low because of the way China soaks up US Treasuries. Treasuries are US government debt used to fund its deficits.

In reality, this measure against Hong Kong is going through for reasons related to a larger US-China rivalry.

The Element of Cultural Conflict

Much of the underlying conflict is a function of disparities in culture.

The US has traditionally been a place that prized the individual and individual rights. People came from all over the world and from different systems. What was good for the individual has been viewed as good for the whole. In other words, it was viewed that this pursuit of self-interest pushes them to do the difficult things that benefit them and contribute to society.

Strong centralized power has been traditionally at odds with American values, which has led to less of a role for central planning. The US, for example, lagged far beyond most other developed nations when it came to establishing a central bank, only doing so in 1913 after a series of “panics” (as they were then known) crushed the economy due to a painful lack of public sector support.

You could call the American system a “bottom-up” approach to governing.

China rules heavily from the top-down. The family and broader state is held in the highest esteem. Namely, what’s good for the whole is viewed as good for the individual.

Nonetheless, China is no longer about traditional communism. Even though many outsiders still refer to China as “communist” and the central ruling coalition calls itself the Communist Party, it is not the level of central planning that characterized the Mao regime. Under such a system, China was largely walled off from the rest of the world, there were no capital markets to speak of, resources were allocated very inefficiently, poverty rates were over 85 percent.

Much of China’s economy is controlled by the state. That type of governing has the advantage of being able to take more control and make decisions quicker. Some sectors are socialized and much of the rest is more or less “capitalism with Chinese characteristics”, with an emphasis on social cohesion.

There are pluses and minuses to each system of governing, but generally much of this conflict between China and the US arises from these disparities.

How can China respond?

In an effort to not escalate tensions, Chinese policymakers take a more reactive stance toward US criticisms and demands on trade and other geopolitical issues.

China’s responses are measured based on how US actions directly strike at their strategic long-run interests, and whether retaliatory options are proportional and will help to avoid escalating the situation further.

Generally speaking, in a geopolitical clash of this nature, the incumbent power has interest in fighting first (because it’s more powerful) while the rising power has interest in fighting later (because it’s still weaker in most areas).

During the “trade war” (very much still a long-simmering issue), China has shown that they’ll retaliate to US measures only once the latter had actually enacted policy.

In such cases, the response was proportional or even less. This was done to limit escalation and because of the fact that the US exports less to China than the other way around, so China has more to lose in pure dollar terms. That approach will likely remain in place.

In response to Hong Kong and other areas, China’s options are broadly the following. Four of these are more geopolitical; two are more financial/capital related.

Geopolitical

Reciprocal tariffs or other trade sanctions

From the beginning, it was unlikely that China would be able to fulfill “phase one” of the US-China trade deal signed in November 2019.

A breakdown in the phase one deal – likely, though perhaps excused in some part due to the unexpected economic fallout that would transpire right after – could lead the Trump administration to increase tariffs on China and lead to a proportional or semi-proportional China response.

At the same time, with the stock market still off from its all-time highs, and its rise speculative given the beaten-down nature of earnings, the trade conflict intensity could be more muted.

China could also look to impose some type of formal or informal limits on its own residents’ ability to buy US goods. This could include limiting tourism or the flow of students studying at US colleges and universities.

China is unlikely to implement tariffs or other trade sanctions on non-trade issues, a policy the Trump administration has pursued in non-trade realms to gain leverage.

Export restrictions

With US sanctions on specific Chinese companies and the US limiting supplies to China, China might consider restrictions on its exports to the US.

This could include medical equipment and supplies. The US traditionally imports ample amounts of these supplies from China.

Of particular interest are rare-earth metals with their technological and other strategic importance. China is an important supplier and finding substitute sources is not easy. The threat prompted the US government to develop rare-earth metal production and capacity within the US.

China has already threatened restricting rare-earth metal exports upon the initial round of sanctions on Huawei in 2019.

China could not only restrict exports of certain goods to the US, but globally to ensure third countries aren’t a middleman sending goods back to the US (similar to how tariffs are often skirted internationally by using a third party).

Take fluid geopolitical stances to suit their relationship with the US

President Trump has in the past linked trade policy with other issues.

For example, on the illegal immigration issue from Mexico, Trump took action by threatening trade relations. As mentioned, while tariffs are not an orthodox way of achieving other policy objectives, Trump is willing to use them as a leverage point in other negotiations.

Trump has done the same with China over the North Korea nuclear situation. In December 2018, Trump asserted: “I have been soft on China because the only thing more important to me than trade is war…If they’re helping me with North Korea, I can look at trade a little bit differently, at least for a period of time. And that’s what I’ve been doing.”

Chinese policymakers can take geopolitical stances that are more or less helpful to suit their relationship with the US on a variety of issues. These changes may not necessarily be known to the general public or appreciated in the financial markets.

Penalties against US companies operating in China

The sanctions on Huawei were also extended to include foreign companies selling direct products of US technology.

China could implement reciprocal actions. It’s already difficult for many US businesses to receive access to the Chinese market as China looks to develop its own services and technologies for its own market. For example, it’s widely known that the world’s largest and most popular websites are not available in China. This includes Google, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Wikipedia, Quora, among many others.

China has traditionally allowed in foreign companies in exchange for a joint venture partnership, and often “stole the blueprints” and replicated the business internally.

China could crack down on US firms in China by increasing the red tape around opening a business in China or preventing the operation of one.

Unreliable entity list

China’s Ministry of Commerce developed an “unreliable entity list” on May 31, 2019 to identify foreign entities or individuals that take actions against Chinese companies through foreign export control enforcement. It was presumably established in response to the Huawei sanctions.

An “unreliable entity” is one that:

i) is boycotting, cutting off supplies to Chinese companies, or taking other unfair actions against Chinese companies,

ii) is in violation of market rules or a breach of contractual obligation in cases where these actions are taken for non-commercial reasons,

iii) takes actions to materially damage the interests of Chinese companies or industrial sectors, and

iv) is believed to be taking actions that pose a threat to China’s national security.

What is the punishment for being an “unreliable entity”?

It’s uncertain, but it likely means something that’s not favorable for selling within China.

With that said, such an “unreliable entity” policy has adverse effects for China itself. If the state is highly intertwined in the economy, the regulatory burden is high, and there’s a bias against foreign companies, this undermines China’s goal of presenting the country as an attractive place to invest.

And even with no official international legal body by which these types of disputes can be definitively resolved, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has some influence and could weaken China’s case for relief within that organization.

Financial

Sales of US assets

China can retaliate against the US by choosing to sell its approximate $1.5 trillion in US government securities. This includes Treasuries, agency-backed securities, and additional assets held through custodians in other countries like Belgium.

Moreover, there’s also a risk in China owning all that debt given the conflict with the US. Unilaterally, the US can choose not to make due on what it owes through its Treasury securities.

China can choose to depreciate its currency (covered in the section below) or it could also choose to avoid a depreciation on its currency from its declining balance of payments situation (namely, running a lower current account surplus, or even running a deficit) by selling US Treasuries.

A desire to sell Treasuries could also be fundamentally different from the basic intention to disrupt the US Treasury or dollar market. China could look to reduce their Treasuries duration to reduce price risk (e.g., selling notes/bonds to shorter-duration bills) or by substituting US dollars for euros, yen, pounds, francs, etc., to diversify their holdings.

Treasuries and USD assets are overweighted in China’s FX reserves relative to trade weights. For many years, China’s holdings of Treasuries have remained steady, neither adding nor selling.

If the move is big enough, the Fed could react because China owns close to 10 percent of the overall Treasury market. That’s high, but not substantial.

The Fed could buy that amount to support the market and keep yields in check.

China’s influence on the Treasury market through the PBOC and state banks isn’t as influential as it was in the past. These days, the main buyers of US Treasuries are Europeans and Asian insurers. The private sector is still around 65 percent of the US Treasury market as a whole.

Moreover, big sales of Treasuries could tighten financial conditions beyond the US. Accordingly, it would be unpopular economically and politically.

Washington considered punishing China through their Treasury holdings – i.e., subtracting damages from future payments – though policymakers did not follow through on the idea.

If there is retaliation or any disruptive measures from either side, it isn’t likely to be through the US Treasury market from either side.

Depreciate the yuan

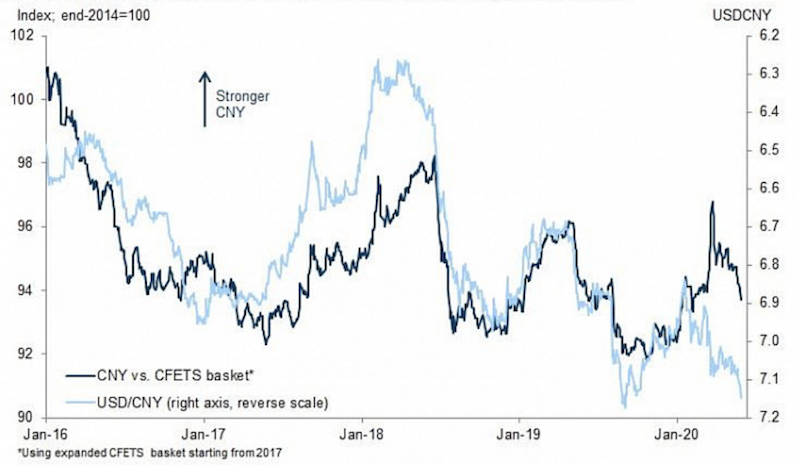

China’s monetary policymakers have been more receptive to depreciating the yuan. They have even taken steps to encourage it, such as weaker daily fixings to the dollar and a basket of other currencies (called the CFETS basket).

At the daily level, the CNY will then trade within a 2 percent band of the midpoint, or a 1 percent allowance above or below the fix. If the CNY gets to the upper or lower bound of the bank, the PBOC and its state banks will be on hand to buy if it gets to the lower edge and sell if it gets to the upper edge as needed.

The CNY is trading against its lowest levels in more than 12 years despite the rapid gains in China’s per-capita incomes relative to the US.

(Source: Trading View)

The CNY has held up better against the CFETS currency basket.

(Source: Wind, CEIC, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research)

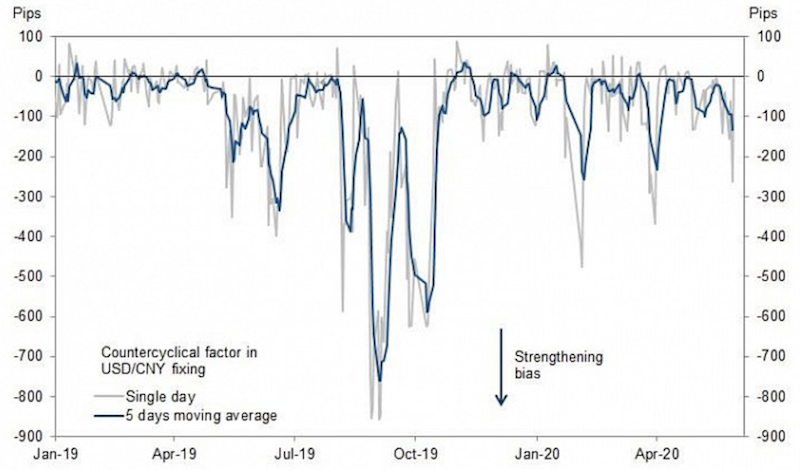

In 2017, the PBOC introduced what’s called the “countercyclical factor”.

This is used to help weigh against strong moves in the currency in either direction and tamp down on its volatility. A more stable currency makes it more attractive as a store of wealth, one of the main two purposes of a currency (the other being a medium of exchange).

Based on the countercyclical factor in the daily USD/CNY fixing, policymakers have been favoring a slightly stronger renminbi.

(Source: Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs Investment Research)

Policymakers generally don’t want to depreciate currencies gradually. If markets pick up on the idea that depreciation is likely, then speculators will short it and makes controlling the descent more difficult.

Instead, when policymakers want to depreciate a currency, they will typically bluff at first and assert publicly they are not interested in a weaker currency before then doing the depreciation all at once.

Doing it all at once helps create a fairly valued market. And a fairly valued market brings with it a two-way market where supply and demand are on par and policymakers don’t have much reason to intervene.

This equilibrium point is where the central bank needs to compensate investors with an interest rate on the currency that offsets the inflation rate and depreciation in the currency based on the underlying capital flow (i.e., the balance of payments surplus/deficit).

Currency weakness can help the export situation. Goods are priced more competitively on the international market. This can, in turn, help their balance of payments. Oil has been low, which is reducing their import costs.

However, currency weakness can also increase pressure on capital flows. Domestic citizens can fear that the currency and assets they hold won’t be worth as much, so want to get it out of the country or into inflation-hedge real assets.

This yuan depreciation in 2015 was handled badly by Chinese policymakers, but they’re less likely to repeat that mistake or be experimental going forward.

If the US imposes higher tariffs on China again, that’s a direct threat to national income and thus weakens the currency.

Some basic math can be used to show what kind of a shock on the currency might ensue. For example:

– 10 percent tariffs on $300 billion worth of goods is $30 billion (multiplying the two together) in terms of the change in national accounting

– The US imports approximately $500 billion from China each year

– Dividing these two quantities, $500 billion by $30 billion, that comes to an estimated currency adjustment of about 6 percent

So, it’s likely that Chinese policymakers would allow for some depreciation if trade tensions are intensified.

Conclusion

Chinese banks do much of their international business, in some form, through Hong Kong. Most of this business is conducted in US dollars.

If the US wants to squeeze Chinese banks and China’s ability to do business internationally more broadly, they will look to put their USD-related activities at risk. It would hit China’s Belt and Road initiative among other international financial operations.

US aggression toward China is likely to pick up both for organic reasons (various geopolitical and cultural divergences) and due to standard election year dynamics.

Markets discount in political campaign promises based on the odds of the politician succeeding in getting elected or re-elected and the subsequent odds of being able to mold policy to those objectives (e.g., based on the credibility of their rhetoric, prospective support from other branches of government).

The market is pricing in increased US-China tensions going forward, such as the recent rise in USD against Asian FX (excluding JPY). This could include tariff threats and/or increases, intensified militarism rhetoric, and/or diminished trade flows as the world shifts away from efficiency to self-sufficiency more broadly.

A hardline stance against China is politically popular in the US (on both sides of the political spectrum) and one that Trump used with effect in his 2016 campaign. Opening up an increasingly tough posture toward China could help his messaging going into the election.

China has some ways it could consider retaliating geopolitically and financially, including:

– Reciprocal tariffs or other trade sanctions

– Export restrictions

– Taking fluid geopolitical stances to suit their relationship with the US in light of their strategic objectives

– Penalties against US companies operating in China

– Sales of US assets (mostly Treasuries and agency-backed securities)

– Depreciating their domestic currency (CNY)

The trade tensions between the US and China will simmer on for a very long time and are endemic of much deeper issues. These include market access, market competition, cyber-espionage, militarism, property rights, IP, among other matters.

The root causes are much more culturally and systemically rooted and go beyond conflicts on trade flows.