How to Determine The Direction Of Financial Markets

How to determine the direction of financial markets? Focus on who’s buying and who’s selling. Too many who invest in stocks (and other financial assets) focus on relative valuation metrics and whether something is cheap or not. What a company is earning right now or has recently earned doesn’t matter. That’s already baked into the price.

The key is to focus on the movement of liquidity, which is controlled by central banks. As they pursue a tighter monetary policy, central banks will either increase interest rates or they will sell assets, usually government securities. This creates more risk in more volatile, riskier asset classes, such as equities and high yield, as liquidity is taken out of the financial system. Likewise, when central banks pursue a looser monetary policy, often known as “easing”, central banks will either lower interest rates or buy assets to push liquidity into the financial system, which will go into financial asset and boost their prices.

It is this process that has the biggest lever on moving global financial markets. This will shed more light into the direction of markets rather than focusing on backward looking chart patterns or traditional measures like earnings and financial ratios.

US stock valuations look reasonable at about 16 times forward-twelve-months earnings. Paying 16x for earnings is traditionally what you might call “fair value”. But value is a measure of risk, not where a market might go.

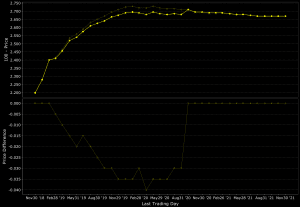

The earnings of the S&P 500 are likely to increase by roughly 10 percent in 2019 to around 177 (of the index’s current 2,790 value as a I write this) for a forward-twelve-months earnings yield of 6.34 percent.

A fall in back-end rates would be required to push the US’s most common stock index up toward 3,000. Hitting that mark is unlikely in the short-term. However, another expected 9 percent to 10 percent earnings growth in 2020, with rates remaining approximately steady, would put 3,000 in view toward the end of 2019.

The fundamental question on stocks is whether the rise in earnings will be sufficient to offset the rise in rates. This is fundamentally how stocks are valued. Namely, they are a series of future cash flows discounted back to the present by an expected return.

How can we predict the future of the rates, bond, and stock market?

In the case of the bond market, to use an example, you can track the following:

1) What are central banks likely to do with their own interest rate policies, and

2) To track rates further out on the yield curve, look at how much debt is coming on the market (i.e., how much supply), who are the potential buyers of that debt (i.e., sources of demand), and what is their ability to buy it (i.e., how much can they spend).

In 2018, a big story in the bond market pertained to the shortfall in bond demand relative to new supply. Naturally, this led to higher rates in 2018, as bond issuance without enough demand to soak it up pushes yields higher and prices down. (Price shares an inverse relationship to yield.) This story will continue into 2019.

What the rates market does is important even for those who focus exclusively on stocks because it influences the rate at which future cash flows are discounted (which make up stock valuations).

Focusing only in terms of US bond issuance, there is at least $80 billion per month coming on the market from the Treasury from higher US fiscal deficits and $50 billion from the Federal Reserve for $130 billion total. The Fed is a seller and the European Central Bank is winding down its asset buying program where it purchased euro zone sovereign and corporate bonds.

Who is buying and who is selling?

In terms of buyers and sellers, you have five main sources:

1) G-4 central banks and governments

2) Emerging market central banks

3) Commercial banking institutions

4) Retail buyers and institutional bond funds

5) Insurance companies and pension funds

Let’s go through them each individually:

G-4 central banks and governments

G-4 central banks and governments are net sellers of bonds, as abovementioned. G-4 central bank balance sheets peaked in Q1 2018 and have been running off since due to more expedient selling by the Fed each quarter. (The Fed is now selling the most they plan to – $30 billion in US Treasuries and $20 billion in agency bonds.)

G-4 central bank flows will decline by an addition $550 billion in 2019. The Fed is selling, the ECB is flat, the Bank of Japan is a buyer, and the Bank of England is flat. The Fed is more of a seller than the BOJ is a buyer. BOJ asset buying is set to continue through the long-term future with its intractable growth problems.

Emerging market central banks

Foreign central bank demand for bonds is constrained due to limited FX reserve growth.

To track global financial flows, it is imperative to track the change in FX reserves. When reserves don’t grow, the foreign demand for US Treasuries and other safe assets isn’t likely to grow either. The shortfall in bond demand among “foreign official” will be exacerbated when the US is increasing its fiscal deficits and pushing more bond supply on the market. Moreover, while US borrowing costs tend to drop when oil prices fall, holding all else equal, emerging market FX reserve growth also tends to fall with the drop in crude.

Currently, an outsized part of the foreign demand channel stems from China. Pressure on the renminbi due to US tariffs and a slowing in its economy has muted demand for dollars (and hence US Treasury bonds) from the world’s second-largest economy. When there is pressure on a currency, policymakers will face the motivation to use FX reserves to buy more of their own currency to help support it.

China can manage this process without tapping into FX reserves by going through the swaps and repos market, but this is only a temporary fix. If China were to freely float its currency, the renminbi would run above 7.00 against the US dollar. The level on its own is meaningless, but psychologically important. Chinese policymakers can’t allow that to happen if they wish to resolve their ongoing trade disputes with the US.

In terms of China alone, the PBOC’s assets peaked in early 2018 at $5.7 trillion. They have declined by $500 billion since, now at $5.2 trillion.

Emerging market reserve growth excluding China should come in around $15 billion to $20 billion per month in 2019. Based on the typical proportions that go into bonds, this should place foreign official bond demand at around $100 billion to $150 billion in 2019.

Commercial banking institutions

Bond demand from commercial bank is motivated by the need to comply with regulatory measures, restrictions, and procedures. Commercial bank demand can also be influenced based on which regulatory instruments are available to banks. For example, when overnight index swaps become cheaper relative to Treasury bonds, banks will be incentivized to buy the former, also muting demand for bonds.

In Q1 2018, a decrease in excess deposits, for regulatory reasons, has limited commercial bank demand for liquid assets.

As a whole, commercial banks’ reserve growth is moving at the slowest pace since 2010. Even if banks were to incur a manageable drop in reserve holdings, they would have a sufficient level of liquid assets to fulfill regulatory requirements before needing to buy more.

In 2019, commercial banking institutions are likely to offset roughly $300 billion in new bond supply.

Retail buyers and institutional bond funds

Retail flows (through institutional bond funds) are volatile year to year and mostly coincide with the direction of the financial markets. Retail investor biases are such that they get more optimistic about investing in the market as it goes up and get more pessimistic when it goes down. This is mostly backwards as it goes contrary to the “buy low and sell high” wisdom, but this is the type of behavior that’s broadly common among this part of the market.

Retail buyers are expected to accumulate about $500 billion in bonds in 2019.

Insurance companies and pension funds

For insurance companies and pension funds, their behavior is mostly the opposite of retail. They are incentivized to keep their allocations of certain assets constant or within a certain range. Accordingly, this causes them to add when prices fall or sell when prices increase. This is more toward the common market theme of “buy low and sell high”.

Consequently, these institutions mostly provide an offset from retail. Also, they tend to always buy – rather than have negative flows in some years, like retail – because they are mandated to invest the contributions they collect from workers.

Due to a rise in interest rates in 2018, insurance companies and pension funds were net buyers. With rates likely to rise in 2019, this is set to continue in 2019. The demand from this source will likely be around $550 billion to $700 billion.

Total Amount of Net Buying/Selling

If we tabulate the values in terms of total debt issuance, total demand, and the ability for our sources to buy them, we are likely to see a withering of bond demand in 2019 of approximately $300 billion to $400 billion. Net bond supply is likely to increase to around $120 billion to $150 billion.

Bond demand in particular is expected to be the weakest since 2008. Adding those two totals together – the combined demand shortfall plus additional supply, this means the 2019 supply/demand deterioration will be expected to come in around $420 billion to $550 billion.

What Does All This Mean For Various Asset Classes?

Bonds

Credit yields should be expected to move higher, both in terms of corporate yields and Treasury yields.

The lowest grade forms of credit should be expected to perform worse, especially as the economy slows and the most at-risk companies face a funding shortfall to service their debt.

Yield spreads should expect to widen (i.e., the difference between the highest grade and lowest grade forms of credit.)

Longer duration bonds, or bonds that expire further in the future, should be expected to perform worse due to their higher interest rate risk.

The only long trade in bonds you might feel comfortable with is the front portion of the US Treasury curve where yields are 2.9% and a bit lower with no material price risk. However, this likely only makes sense for domestic US buyers, as currency hedging costs can wipe out the yield entirely or even make it negative.

Stocks

The earnings picture on stocks is bullish while the rates and liquidity picture is bearish. This means likely more volatile and flatter equity markets moving ahead. If the rise in earnings can’t offset the rise in rates, this will be a problem for equity markets. It has been for a large part of 2018.

The Federal Reserve’s rate hiking plans in 2019 will have a substantive effect. Right now, the market is pricing in just one Fed rate hike in 2019 after the move forthcoming in December 2018.

If they go based on what’s discounted in the curve, this will limit the Fed’s influence for its rate hike policy to bleed into markets in the form of volatility and a re-rating of asset prices downward. Overall, this would be beneficial for financial stability reasons.

The math is such that each 25-basis point parallel shift in the yield curve impacts equity prices by 5 percent. The rise in yields in October was influential in causing the approximate 10 percent price fall in the S&P 500.

Moreover, there is little need for the Fed to hike further given inflation risks are slanted toward the downside. Within the equity markets, higher rates are less impactful on growth as they are for more rate-sensitive sectors like value and defensive areas of the market like utilities.

Rates

Rates are a modest short; or in other words, one should expect them to go up but not in a big way.

Commodities

Commodities are a very volatile asset class – generally about 40%-100% the volatility of stocks depending on which ones or how they’re weighted as a basket. And commodities are too broad overall to discuss collectively given each one’s unique supply and demand profile.

However, lower liquidity and higher inflation-adjusted interest rates are less supportive of commodity prices.

Dollar

The dollar has increased since April 2018 given it’s been the only developed market that’s been semi-aggressively raising rates. (Canada and the UK have as well but not to the same extent.

Given the rate hiking cycle is likely – or should be – in its final stages, longer-term structural problems with the US dollar will begin to take form and shape its valuation. Notably, these include the fiscal and current account deficits of the US. When there are deficits in these accounts, that means funding is necessary to plug them and usually entails a weakening of the currency.

Owning gold is another way to gain access to this theme, as the dollar largely trades opposite of gold for historical reasons (going back to the Bretton Woods monetary system in place from 1944-1971).

Euro

The euro is probably not as undervalued as the average market participant believes given inaccuracies in perceptions regarding its current account surplus.

Final Thoughts

To understand where financial markets will go, one has to consider the buyers and sellers, look at how big they are and what are their motivations. From looking at the bond market, we can see that neither equities nor bonds are especially attractive at this juncture in the market cycle.

Going ahead, because of the expected increase in volatility and up and down movements in asset prices, this market will favor the trading crowd more than it will the “buy and hold” crowd. The easy money that came with the 2009-2018 bull market is now over and achieving consistent gains will increasingly rely on the skill of the trader navigating his or her markets of interest.