The Coming Squeeze in Financial Asset Returns

As a day trader, you probably don’t pay a ton of attention to the longer-term picture. Or else you do but it takes a backseat to what’s going on in the present with respect to your trading. Day trading is inherently a form of trading where positions are open for short durations (a day or less), either long or short, usually with little attention placed on long-term trends.

Nonetheless there are still things to be gleaned from studying what’s going on in a macroeconomic sense.

As of the end of 2018, the global economy is fine. Debt is high and growing in both developed and emerging markets, but serviceable with low interest rates, and incomes and assets more than high enough to service these liabilities.

However, the longer term, when the economy does turn down, looks scarier. The next downturn is not only likely to be about debt that can’t be paid (as is the case normally), but rather pension and healthcare obligations as well. As the population ages, there are increasingly too many of these promises that can’t be kept. Unfunded obligations related to healthcare, pensions, and private and public debt are more than $220 trillion, or about 11x-12x GDP. There’s no way they’re ever going to get enough tax revenue to cover that.

The issue with pension funds specifically is two-fold:

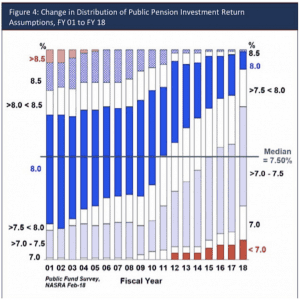

(1) They extrapolate their past and current performance into the future even though future returns won’t be like past returns. The average pension fund assumes a future annualized return of 7.5% (see image below) off a portfolio that’s roughly 70% stocks, 20% bonds, and 10% alternatives like real estate, private equity, and hedge funds. That’s not happening.

Asset prices have been pushed up since early 2009 from interest rates being compressed down to zero and $15 trillion worth of central banks buying assets.

Now they are in the process of trying to reverse that (at least the US Federal Reserve so far) but they can’t do it too much without inducing volatility and compression of asset prices. There’s a lot of debt globally, and making all that debt more difficult to service will slow down growth, which will hurt the future expected returns of asset prices. And asset prices are more sensitive to this process when rates are low because of the way it extends the duration of assets.

When public and private pensions have their discount rates reconfigured to model what they’re actually likely to achieve in long-term returns (about 5.5% for private pensions), trillions of dollars’ worth of additional liabilities will come to the surface.

A portfolio of 70% US stocks, 20% intermediate bonds, and 10% alternatives has achieved 7.7% annualized returns over the past 20 years. Back then, people were getting 6 percent on a short-duration US Treasury bonds and sustainable economic growth was around 3 percent. Now you get 2.5-3.0 percent on short-term US Treasuries and long-run growth is somewhere around 1.5-2.0 percent.

And (2) they aren’t taking in enough funds to cover for future liabilities as the demographic situation gets worse.

It’s essentially the same problem with Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid liabilities at the federal level. The liabilities associated with those programs are going up as the population ages and more people become eligible while they aren’t able to take in enough tax revenue to fund those. The US federal government is in a quagmire where it can’t ever collect enough revenue to pay off its debt and adequately fund its obligations.

Private sector pensions are facing the same problem. With the squeeze in returns and current pace of liabilities exceeding incomes, they either need to take more from each person’s check or they need to find new ways to boost returns. Neither of them are eminently feasible.

Retirees expect a large amount of spending power (to cover retirement and healthcare) while no longer producing while workers expect spending power on par with what they’re giving, and all of this can’t be satisfied.

They’re getting squeezed on both fronts and mathematically it doesn’t work. This is also something one has to account for when valuing certain companies. Many of the older companies like General Electric, AT&T, Ford, General Motors, and so forth, have burgeoning unfunded pension liabilities.

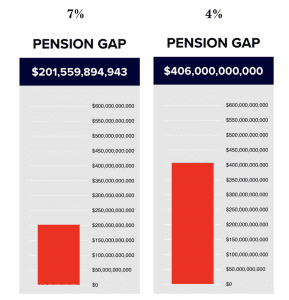

In California, if expected returns were to fall from 7% to 4%, the pension gap would rise from $200 billion to $400 billion:

(Source: http://ipfiusa.org/).

Takeaway

For those who hold long-term portfolios, these issues can have material implications. We know that financial asset returns of the past aren’t going to be like the returns of the future.

US stocks have given 7.2% annualized since January 1998 and 10.3% since January 1972. Intermediate-duration US Treasuries have returned 4.6% annualized with cash giving 1.9%. Interest rates are still near an all-time low, which means little ability to further stimulate financial asset markets. People expecting 10% annual returns on their stocks over the next 10+ years are going to be disappointed.

In terms of what comprises the returns of financial assets, you’ve got a little bit less than 2% growth, 2% inflation, with some contribution from dividends, maybe up to 2%. For stocks, that means somewhere up to around 6% long-run returns.

As mentioned, there isn’t a ton of room left in the yield curve. You can’t lower short-term rates much. There isn’t as much room in the back-end of the yield curve like there was, meaning asset purchases (“quantitative easing”) will have a more limited effect. Asset-buying might incentivize financial investment but it doesn’t do a lot in term of making its way into the real economy to improve productivity outcomes.

In terms of policymaking, eventually monetary policy is going to have to go outside the conduit of the banking system and financial markets. This will probably take the form by either breaking the barrier between fiscal and monetary policy by monetizing the debt – the central bank buying it from the government and effectively retiring it – or else by putting money directly in the hands of consumers and tying it to spending incentives.