Is a Currency War the Next Big Global Macro Event?

It is very likely that currency policy will take on a much bigger role in the next recession. As the ‘trade war‘ associated with the export and import flows between countries plays out, most notably between the US and China, a ‘currency war’ is likely to be one of the next big macro themes as the global economy slows.

All advanced economies are already at, below, or very near the zero interest rate level at the front end of the curve. It seems like that all will be there in the next slowdown. And several more will be at zero in the belly and long-end of their interest rate curves.

Expansionary fiscal policy could help give room. But that’s a political process that requires bipartisanship, which is less likely in an environment where there’s more bi-modal ideological distribution among elected political leaders. So, debt monetizations and the use of currency policy as stimulatory channels will naturally have to take more of a role.

With respect to the ‘trade war’ tie in with currency policy, the more the US pushes against China on trade, the more pressure there is on the yuan (CNY).

If China offsets weaker trade with the US through a lower CNY – which it has to some degree already – that puts more pressure on other countries to push their currencies lower as well. This will help them avoid becoming less competitive on the export/manufacturing front relative to China. That pushes more flows into gold as a hedge against the deprecation of the value of money.

A weaker CNY relative to the USD gives China a trade advantage relative to the US. In a straightforward way, if your currency is cheaper your products and services are more attractive to others. It’s similar to giving a discount.

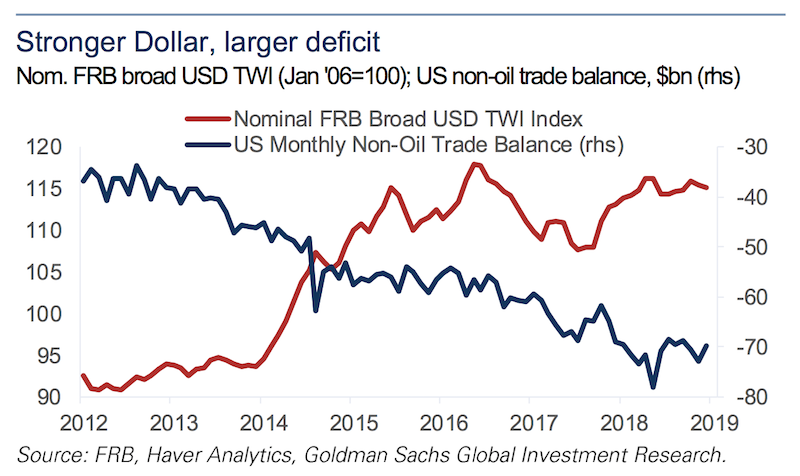

The strength of the US dollar is inversely correlated to the size of the US trade deficit. There is a causative element behind this – if your currency is more expensive, your products and services become less attractive to foreigners.

Even though the Trump administration recently deemed China a currency manipulator, it does not fit the Treasury’s definition of what a currency manipulator is. As a whole, currency manipulation has fallen markedly since the 2003-13 period when several nations bought foreign currency to devalue their own. This helped boost their global competitiveness.

The yuan is, however, a managed currency. It is not freely floated. China has nonetheless not managed it lower over the past decade, but rather to resist depreciation.

It is changing its economy from a manufacturing-based, export-centric model to one that focuses on domestic consumption. All major developed market economies have a very high percentage of their overall output based on consumption (e.g., about 70 percent in the US). After all, the end and objective of all production in the capitalist system is consumption. In light of this, a more stable or even stronger currency can be useful. When your currency appreciates, it can buy more goods and services on the international market. China is also a commodity importer.

So, China is not actively trying to depreciate its currency, though it certainly has in the past. If China did not lean against depreciation, the yuan would likely be weaker than it is currently and the US trade deficit would likely be larger.

One of the largest threats to the macro-economy today is China’s potential to free-float its currency. A China devaluation would depreciate it against the USD and other reserve currencies.

Many other countries, particularly those that are export dependent, would follow suit to avoid their global competitiveness from being throttled, potentially leading to a ‘currency war’. This would cause the dollar to rise in relative terms. The prices of various commodities, typically priced in dollars, would increase. USD denominated debt owned by various countries would rise in value, hurting countries that borrow in dollars (a similar effect to a rise in interest rates). Risk asset would be decline and the price of gold would rise.

While the US and China, as of November 2019, appear to be resolving some of their trade differences, the geopolitical conflict between the US and China will continue on for a long time. There may be some form of détente between the two countries, especially as the Trump administration gears up for its re-election campaign and could use a stronger economy and stock market. But seeing an emerging power butt up against an incumbent power as they compete for economic, military, and technological influence is something that happens over and over again throughout history.

The 2003-13 Period

Over the 2003-13 period, many countries around the world engaged in foreign currency purchases to weaken their exchange rates.

The rate was a material fraction of GDP, running at around $1 trillion in FX purchases per year. (They are now around $100 billion per year.)

This behavior tends to be self-reinforcing. If one country is trying to weaken its currency to gain a price advantage in global trade, this will encourage other countries to follow suit to keep competitiveness level in relative terms.

This led to a stronger US dollar. When the financial crisis came, the strength of the dollar hurt certain sectors of the economy, such as exporters, manufacturers, and many multi-national companies. This resulted in job losses and a slower recovery.

From the US’s point of view, during that period, they needed a devaluation. When you’re in a deflationary environment, devaluing your currency is stimulative. You can export more, corporate earnings get a boost, and non-hedged foreign borrowers can more easily make their debt payments.

In 2014, government purchases of foreign currency declined as the global recovery improved and currency manipulation became less of an issue. Generally, FX manipulation is fundamentally a sign of economic weakness. Arguably, there was also less of an understanding of the drawbacks of currency devaluations at the time and both G-10 and G-20 nations have since agreed not to use depreciations as a viable way to gain a competitive advantage over other countries.

The most common currency manipulators today are not China. The most interesting cases of currency intervention occur in the smaller Asian economies – Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, and Singapore, in particular. They have large surpluses and maintain them by weakening their currency.

The US Treasury uses a criteria to look closely at countries with large bilateral surpluses with the US that also have an external surplus. This puts countries like Germany, Italy, Ireland, and even Japan on the map. But Ireland is a tax story and they compete heavily on that, so that’s not really a foreign exchange matter.

South Korea is under watch with its weak currency, but that’s not a centrally planned intervention thing. South Korea’s financial outflows aren’t hedged and its pension system invests in a lot of foreign assets. That weakens the currency.

The Treasury’s criteria don’t consider any of that. Using only the bilateral goods surplus ($40 billion threshold), goods surplus with the US ($20 billion threshold), current account surplus (2 percent of GDP), and net FX purchases (2 percent of GDP, plus intervening in 8 of past 12 months) is a cookie-cutter and flawed way to get a complete picture of what’s going on with respect to the FX intervention front.

China has not intervened (to depreciate) and its trade surplus is quite small. Even though the US declared China a currency manipulator, the designation has more or less no meaning.

The upcoming period

While currency manipulation has not been an issue over the past 5-6 years, it’s likely to be an issue when the next recession hits or if there’s simply a slump in growth to near-recession levels. When income and wealth levels drop, demand for products, services, and financial assets declines. That puts pressure on countries to stimulate export demand by devaluing their currencies.

Moreover, traditional monetary policy tools will be less effective. Developed Europe and Japan already have negative rates.

The US has only about 150bps to work with at the front end of its curve. Fiscal policy’s capacity to stimulate the economy will face political challenges. Increasingly, debt monetizations – or the process of the central bank buying the debt and effectively retiring it – and FX devaluations will become needed alternative ways to fight a downturn.

Because less economically robust countries in emerging and frontier markets are most likely to engage in this practice, this will cause the US dollar to appreciate in relative terms. This will once again be likely to hinder the US recovery.

The US also runs a current account deficit of around 2 percent of GDP. Its external debt is around 45 percent of GDP, meaning the US has to issue a lot of debt to foreigners to fund its deficits. If the US had balanced trade, this external debt would start to shrink in relation to GDP. In general, the US external debt stock is not sustainable.

Trade surpluses and deficits are a zero-sum game. So, large surpluses are generally frowned upon by macroeconomists because there are corresponding deficits being created somewhere else, which is turn need to be funded and can’t always be adequately done.

Some macroeconomists believe that a +/- 3 percent surplus or deficit situation can be exceeded as long as surplus countries are not increasing their net foreign assets relative to GDP and deficit countries are not decreasing their net foreign assets relative to GDP.

Why 3 percent?

Generally speaking, it is hard for a country to run an external debt to GDP ratio of more than 40 percent for an elongated period. Simply based on the empirical evidence, the 40 percent threshold was the point at which a country’s odds of default increased markedly. The odds increase further as it goes higher.

If we were to assume that global growth rates are about 3 percent in real terms and 6 percent in nominal terms (i.e., 3 percent growth and 3 percent inflation), if we multiply this 40 percent by 6 percent, we get a figure of 2.4 percent as a general sustainable current account deficit. (This assumes that the deficit is financed in domestic currency where the rates and payments can be controlled in all the usual ways, unlike if it’s denominated in a foreign currency that’s under the purview of a different country.)

If we bump this external debt to GDP ratio up to 60 percent – a net debt figure that no country has ever sustainably managed – we have a figure of 3.6 percent.

Averaging the two comes to about 3 percent. If global growth is lower, then this equilibrium estimate naturally needs to come down.

It also depends on the country. What’s their mix of trading partners? Is it a reserve currency where funding deficits is more sustainable? What’s its net foreign asset position? If a country generates more income on foreign assets relative to what it pays out on liabilities – like Japan, for example – this extra income could support a higher current account deficit if necessary.

Countries with reserve currencies enjoy the advantage of being able to sell their debt more easily to the rest of the world in comparison to a non-reserve currency country.

Even though the US has a balance of payments issue with fiscal and current account deficits, the US dollar is the most widely used currency in a variety of ways. So, there is a large amount of foreign demand for it because of the safety and liquidity the dollar provides (generally through US Treasuries).

Therefore, the US can keep its deficits higher relative to a country that has a lack of economic and political stability, less robust institutions (e.g., rule of law), higher levels of corruption, less support for commercialism and innovation, less internal investment, less capital markets development, and so forth.

Will a ‘currency war’ be an extension of the ‘trade war’?

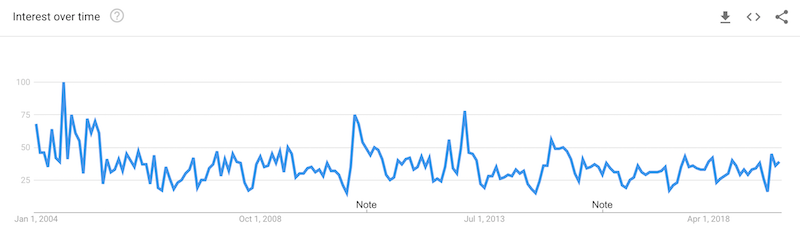

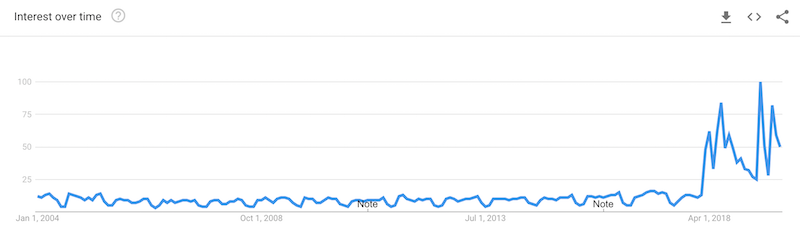

As of the end of 2019, the term ‘currency war’ is not yet very popular.

According to Google Trends, there have been some spikes here and there (e.g., Brazilian finance minister calling QE a ‘currency war’ about ten years ago), but it’s been nothing like the now-popular ‘trade war’.

A genuine currency war would not be like QE. While QE does weaken currencies, it has some beneficial impacts because it eases monetary policy. When the US embarked on QE, it was not only beneficial to the US but to other countries as well. It has the effect of lowering interest rates, making borrowing easier, which in turn helps spending. This helps increase imports because people have more buying power and helps to offset the export effect generated through the currency weakening.

So, QE or lowering interest rates is not exactly a currency war, which has the implications of engaging in a zero-sum game.

On the other hand, borrowing in your own currency to buy foreign currencies to devalue the exchange rate is very zero-sum in nature. One might gain in terms of exports, but the other country will lose without any compensating benefit. If any policy is going to be termed a currency war, that type would be it.

Could the US launch a ‘currency war’ to benefit itself?

The Trump administration doesn’t necessarily have a weak dollar policy, but it has considered intervention measures through the Treasury to counteract what it perceives to be excessively tight monetary policy from the Federal Reserve.

Foreign countries have acted by buying US dollars (borrowing in its own currency) and investing them in US Treasuries.

The US could act by buying a foreign currency – e.g., CNY, EUR, JPY – and investing it in the government bonds of whatever country/ies it selects.

It could also choose to levy taxes on foreign investors if it didn’t want to go the FX route. Lowering taxes on foreign investors helps appreciate a currency because it increases demand for domestic assets. Increasing taxes helps depreciate a currency by the opposite effect.

Will the US intervene in the currency markets?

For now, it’s unlikely.

For one, the optics would be a bit strange. When devaluing your currency, you’re buying the currency of a foreign country, typically through their sovereign debt. If the US did this by buying China’s debt, this would effectively mean that the US is lending to China. This is strange in the context of an ongoing trade conflict of some form. So, the US would likely want to diversify what other foreign currencies it’s buying.

Second, the Treasury has limited resources to effectuate a dollar depreciation plan. Either Congress would need to pass a law that gives the Treasury more borrowing authority. Or else the Federal Reserve would need to get involved. Neither of those are likely.

In terms of the historical record, the Fed has cooperated with the Treasury, even though dollar policy is explicitly within the Treasury’s domain.

Today, the Fed likely has no interest in participating in managing the dollar. The Fed would likely need to lend the Treasury cash, which would likely involve the Treasury making a formal request for purposes of currency intervention. The Fed would be taking no risks on its own books – those would fall directly to the Treasury. Nor would it impact the Fed’s ability to pursue its statutory dual mandate of maximum employment within the context of price stability. The Fed could actually use FX intervention to its advantage to deliver on its mandate, as it can only impact the dollar indirectly, not through direct control over currency policy.

Could a tax on foreign investors work to weaken the USD?

From an optics standpoint, a tax on foreign investors meshes well with the idea of a ‘trade war’. It works better than direct FX intervention that essentially amounts to lending to China (if the Treasury were to work to devalue the USD against the CNY directly). A tax is similar to a tariff.

Moreover, a tax on foreign investors would be more likely to fall where it’s supposed to, rather than flowing, at least partially, into a tax on US companies and consumers. There’s been debate about where the economic effects from US tariffs on China are falling.

Early on the trade conflict, the US appeared to be targeting goods with demand elasticities that would put the brunt of the effects on Chinese producers. As the US dipped further into the export base, this became harder to do. So, the effects are non-linear, with initial tariffs putting more of the burden on China by targeting specific goods that are more easily substitutable elsewhere and possess higher demand elasticities.

If a foreign tax was placed on investors, that would weaken the dollar to some degree and hurt imports relative to exports (in essence, hurt consumers relative to producers). US companies that do business with foreign clients would not want to pay such a tax.

With that said, it’s not certain a tax of that nature could reduce the bilateral trade deficits it has with other countries by that much. The revenue collected from the tax also wouldn’t contribute much to reducing the fiscal deficit.

Nonetheless, a weakening of the dollar is eventually necessary to reduce the US’s external debt as a percentage of GDP. But a foreign investor tax is unlikely to contribute much in getting there.

Should the US intervene in the currency markets?

The US dollar will need to depreciate over time because of its large intractable twin deficits (i.e., fiscal deficit and current account deficit) and its bloated net external debt as a fraction of output.

Over the long-term, this depreciation will occur.

In the short-term, the dollar has been held up through “high” nominal interest rates (relative to other G-7 countries), a relatively rosy US growth outlook compared to the rest of the world, and through the dollar’s status as the world’s top reserve currency wherein investors and reserve managers demand liquidity and safety.

The recent fiscal expansion passed by the TCJA at the end of 2017 also increased demand for foreign products and services, boosted imports, and expanded the trade deficit. It’s a basic macro-accounting reality that the US can’t borrow externally to cover an increasing fiscal deficit while keeping up business investment without running a larger trade deficit.

The fiscal stimulus also caused the Fed to tighten more than it would have otherwise, though it now reversed some of that tightening.

So, from that vantage point, a lot of the dollar’s overvaluation is due to internal policy choices.

Inevitably, I would expect the printing of money and borrowing by the federal government to grow. This is because the size of our total debt obligations and non-debt obligations (e.g., healthcare and pensions most prominently) is large and growing at a rate that is faster than the incomes being produced to meet them. This will weaken the dollar and, over time, reduce its role as a global reserve currency.

Simply put, US finances are weak, so a depreciation of the dollar is inevitable at some point.

Foreign holdings of US dollars (about 62 percent of all FX reserves are held in dollars) are also high relative to what one would want to hold to have balanced reserve portfolios.

What is Trump’s actual position on the dollar?

There’s some perception that Trump wants a weak dollar policy.

A weak dollar policy has the following effects:

- It is good for those who owe money in that currency (dollar borrowers) and bad for those who are owed money in that currency (dollar creditors).

- It effectively reduces the buying power of US dollar holders in comparison to the rest of the world if the exchange rate depreciates in relative terms.

- It is stimulative to risk asset prices and to domestic activity (producers and exporters and those who sell goods and services to the rest of the world benefit).

- Works to increase a country’s inflation rate.

Someone with a fixed-rate mortgage, for example, would benefit from a weak dollar policy, holding all else equal. A resultant higher inflation rate also helps to pay back in cheaper money.

In general, any change in an exchange rate or in an interest rate is good for one party and bad for another. In the markets, it’s important to understand who might benefit and who will be worse off as a result of these changes.

Timeline of Trump and Mnuchin’s comments on the dollar

January 16, 2017

Trump: “Our companies can’t compete with [China] now because our currency is too strong. And it’s killing us.”

April 12, 2017

Trump: “I think our Dollar is getting too strong, and partially that’s my fault because people have confidence in me. But that’s hurting – that will hurt ultimately.”

July 25, 2017

Trump: “I think low interest rates are good. I like a Dollar that’s not too strong. I mean, I’ve seen strong Dollars. And frankly, other than the fact that it sounds good, lots of bad things happen with a strong Dollar.”

January 24, 2018

Mnuchin: “Obviously a weaker Dollar is good for us as it related to trade and opportunities, though the currency’s short term value is not a concern of ours at all… longer term, the strength of the Dollar is a reflection of the strength of the US economy and the fact that it is and will continue to be the primary currency in terms of the reserve currency.”

August 30, 2018

Trump: “As president, there’s something really nice-sounding about the fact that our Dollar is so strong and so powerful. The bad news is that it makes life more difficult when you’re looking to sell product to the rest of the world. And they are cutting their currencies very substantially, far more than they should be allowed to do. And we’re not being accommodated. I don’t like that.”

March 2, 2019

Trump: “I want a strong Dollar, but I want a dollar that’s going to be great for our country, not a Dollar that’s so strong that it is prohibitive for us to be dealing with other nations and taking their business.

July 3, 2019

Trump: “China and Europe playing big currency manipulation game and pumping money into their system in order to compete with USA. We should MATCH…”

July 18, 2019

Mnuchin: “[Changing the US dollar policy] is something we could consider in the future, but as of now there’s no change to the Dollar policy.”

July 26, 2019

Trump: “I didn’t say I’m not going to do something [on the Dollar].”

August 5, 2019

Trump: “China dropped the price of their currency to an almost historic low. It’s called “currency manipulation.” Are you listening Federal Reserve?”

August 8, 2019

Trump: “As your President, one would think that I would be thrilled with our very strong Dollar. I am not! The Fed’s high interest rate level, in comparison to other countries, is keeping the Dollar high, making it more difficult for our great manufacturers.”

August 23, 2019

Trump: “Germany competes with the USA. Our Federal Reserve does not allow us to do what we must do. They put us at a disadvantage against our competition. Strong Dollar, No Inflation! They move like quicksand. Fight or go home!”

August 28, 2019

Mnuchin: “The Treasury Department has no intention of invention at this time. Situations could change in the future but right now we are not contemplating an intervention.”

August 30, 2019

Trump: “The Euro is dropping against the Dollar ‘like crazy,’ giving them a big export and manufacturing advantage… and the Fed does NOTHING! Our Dollar is now the strongest in history. Sounds good, doesn’t it? Except to those (manufacturers) that make product for sale outside the US.”

On the topic of China’s currency policy

China no longer manipulates its currency in the sense of holding it down to keep an artificially large trade surplus.

China does manage it through what’s called the daily “fix” or a median point around which the CNY (also known as the yuan, renminbi, or RMB) is allowed to trade. China’s central bank, the PBOC, calculates this median point – not publicly available – and has some level of latitude to manage around this point.

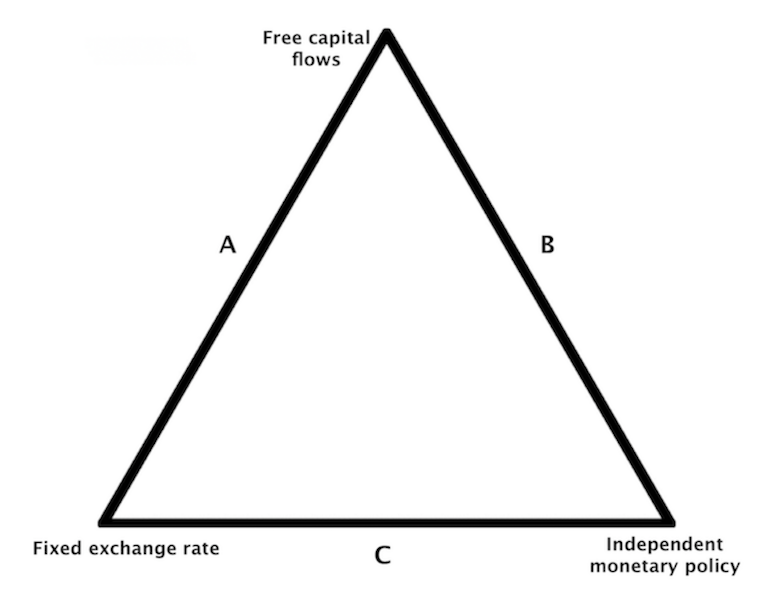

The PBOC will directly intervene in the currency markets, as will the state bank on behalf of the PBOC. Moreover, China also tightly controls its capital flows in and out of the country. Given the need to manage its currency – a quasi-peg – and desire to still maintain an independent monetary policy, China must necessarily control its capital flows. This is part of the “trilemma” that impacts currency policy.

If we think of a triangle between the policy choices of a pegged currency, independent monetary policy, and free flow of capital in and out of a country, a country can typically only choose two of those. An exception would occur when, for example, capital flows are small enough to not interfere with the exchange rate or the ability to run an autonomous monetary policy.

China is currently on side C.

For reference, the US is on side B (free capital flows, independent monetary policy, free-floated exchange rate) and the euro zone is on side A (free capital flows, but the euro pegs many countries to the same currency, which doesn’t allow for an independent monetary policy).

So even though the US, China, and euro zone taken collectively are the first-, second-, and third-largest economies in the world, their monetary and currency policy setups are quite different with respect to their management of their exchange rates and capital flows, and general autonomy in setting monetary policy.

And despite the US recently dedicating China a currency manipulator under the 1988 trade law, it doesn’t mean much, and China doesn’t qualify under the 2015 law.

Does the USD/CNY exchange rate have an impact on the US economy?

The US and China and the two largest economies in the world, so it matters for not just bilateral trade but global trade more broadly.

The dollar-yuan exchange rate recently reached its highest point since the financial crisis, and the USD is also the strongest it’s been against most other currencies for a while now. Below shows the value of the USD on a trade-weighted goods basis against other major currencies:

A dollar that is too strong impacts the health of certain key parts of the economy, like farming and manufacturing. This bleeds over into political movements, particularly in swing states like Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio, where presidential elections are often decided.

But ironically, when the US escalates trade pressure on China, this is a direct attack on China’s national income, decreasing the value of the yuan. To unwind this adverse effect, China will be motivated, holding all else equal, to devalue its currency.

Without China’s current management of its currency, the yuan would actually be weaker than it would be otherwise, as China shifts to a consumption-based economy (where a stronger economy helps in buying more imports) and away from an export-based, manufacturing oriented economy. Accordingly, if China didn’t do this, the bilateral trade deficit with the US would actually be larger.

Is the yuan overvalued?

It’s a complicated question.

For China, the exchange rate peg is not as important anymore because of the restructuring of their domestic economy. It no longer has to make its goods competitive in the world as they go toward a domestic-based economy.

If China wanted to balance its financial account, the CNY would likely go lower. This equilibrium measures the desire of foreign investors to hold Chinese assets relative to the desire of Chinese savers and investors to hold foreign assets. More money would likely flow out of CNY and into foreign assets. But this would require China to give up its capital controls, which is unlikely at the moment.

The CNY currently is valued against the dollar in the same way it was approximately eleven years ago in 2008. But the Chinese economy has gained on the US economy since then, growing at about three times the relative annual rate.

From the US’s vantage point, we want a devaluation. A devaluation helps to get your pricing in line.

The US is in an environment where inflation is hard to come by because there’s a lot of debt. A small uptick in interest rates diverts more money and credit toward servicing the debt, which means less available to invest in goods, services, and financial assets.

The US also has a lot of debt that it sells to foreigners denominated in USD. As mentioned above, this is now around 45 percent of GDP, which is a lot. When you’re in the 40-60 percent range, you’re in a zone that becomes difficult to sustain. Even having the world’s top reserve currency, having to rely on foreigners to buy a lot of your debt can be a dangerous thing to run your country on. The US largely takes it for granted that it’ll be able to sell a lot of debt to the rest of the world given the power of the USD, but this would be a big problem for most other countries.

When you have a lot of foreign debt, you generally want your currency to go down. This helps to create debt relief. A devaluation also helps trigger a rally in the stock market (and other risk assets), and is typically bullish for alternative currencies like gold.

The structural issue between the US and China and that US GDP per capita is very different. US GDP per capita is about 6x that of what it is in China. Eventually our prices will need to get in line and that’s not going to happen by US incomes being cut to the level of China’s incomes.

And it’s not going to happen by China’s per capita incomes coming in line with US per capita incomes. But they will eventually need to converge closer together.

China’s currency and assets are cheap in dollar terms. This makes a devaluation of the USD in relation to CNY likely. This will help to boost the US economy and also makes (yuan-denominated) investments in China attractive for foreigners (at least for those whose currencies are valued too high relative to the CNY).

In the 2003-13 period, the main source of USD strength was a consequence of other countries intervening in their markets to gain a competitive trade advantage. Since 2014, the main source of USD strength has been higher nominal bond yields against other developed economies. The BOJ had been engaged in quantitative easing; the ECB began in 2014, and the Fed began tightening policy in December 2015, raising the dollar in relative terms.

The US intervening directly in the FX markets to bring down its currency would be a big shift relative to what we’ve become accustomed to over the past few decades. Moreover, the US is not set up to intervene in the currency markets directly. The Treasury has FX reserves, but not of a sufficient quantity to materially move the dollar.

The Fed has the power to influence the dollar. But the effect is indirect. It’s focused on employment and price stability, and not the exchange rate.

All other major economies don’t want a stronger exchange rate either (e.g., Europe and Japan are facing their own disinflationary issues).

Could this lead to a ‘currency war’?

A ‘currency war’ could be characterized by countries with relatively high interest rates being economically punished, leading them to ease. Because currency devaluations are a zero-sum game both between countries and between individual market participants (i.e., a borrower benefits, a creditor is worse off), this leads other countries to ease in conjunction creating a tit-for-tat “war”.

Relative exchange rates typically don’t change much in these types of scenarios and alternative store-holds of wealth like gold tend to benefit.

In the current case, we have low interest rates in all developed markets. This is a function of weak growth rates and lots of central bank liquidity finding its way to assets, pushing down their forward yields.

The main risk for a currency war these days is probably in relation to its tie-ins with the US-China trade conflict. When the US escalates, China could simply tote up the amount of goods likely to be subject to tariffs and the rates on them, take that amount and divide by the total export base, and depreciate the yuan against the US by that amount.

This sharp depreciation would hit risk assets. It would incentivize other Asian economies to depreciate to avoid losing their competitiveness on the global export market relative to China. The yen is a “risk off” currency and would see inflows relative to virtually all other currencies (including USD). So, Japanese monetary authorities would be likely to intervene in the FX markets and European officials would be likely to resume bigger easing measures than anticipated. This would also increase pressure on the Federal Reserve to ease.

So, the delicate situation with China is probably the most likely point where an FX devaluation spiral would emanate from. China is aware of this, and the devaluations they have done against the USD so far in the trade war have been small and stealth. And the US should be aware of this risk as well given trade war escalation is the impetus that could set off a chain of events. It’s not very likely that we could have this type of spiral based on trade conflicts, but it’s still nonetheless a risk.

China would likely only go this route if the drop in its export performance required this type of move. China’s exports may be down compared to the US, but is still growing relative to non-US markets. Its trade surplus is increasing, so for now it’s not an issue.

Another issue would be if China had trouble controlling its capital account. Though the Chinese government has largely done a good job tying up its financial account, if the leaks were ever strong enough that fighting these outflows were no longer feasible or worth it, then the yuan could see a depreciation that way.

More likely, we’ll see this type of currency devaluation as a consequence of inadequate policy room from central banks, leading to secondary and tertiary easing measures, like FX depreciations and debt monetizations.

Could China engage in a ‘capital war’ with the US as retribution for the ‘trade war’?

Many countries, including China and Russia and others (allies and non-allies of the US), want to reduce the world’s dependence on the US dollar in global transactions.

So, the question is, could a trade war or currency war stimulate a capital war as well? In other words, would China want to sell US Treasuries (the way it predominantly stores USD reserves)?

If China were to sell Treasuries, it would have to shift its reserves to something else. The issue with other countries, like the other two top reserve currencies – i.e., EUR, JPY – is that these debt markets are not particularly deep. The ECB and BOJ control a very large proportion of their own sovereign bond markets for domestic policy purposes (i.e., quantitative easing to lower rates further out on the curve).

With China’s reserve portfolio, if it wanted to offload the $1.1-$1.2 trillion in Treasuries it owned (more than one-quarter of the $4.1 trillion in Treasuries owned on foreign balance sheets), it would need to find that amount elsewhere.

The Treasuries market is deep, liquid, and also provides a positive yield. So, the allure of Treasuries isn’t just the liquidity or the status of the dollar as the world’s top reserve currency, but forgoing that 1.5 to 2.4 percent yield would come at a material financial cost. $1.2 trillion earning 2 percent per year is $24 billion in interest income. That’s 0.2 percent of China annual GDP.

Russia has taken steps to diversify out of the USD, moving more of its reserves into EUR, CNY, and gold. Because of how prevalent negative yielding debt has become throughout the world, more and more reserve managers will look toward the CNY and its positive yields (2.5 to 4 percent as of the latter part of 2019) as an alternative to Treasuries.

The USD is still over 60 percent of all global reserves, which is very high relative to the figure countries want to stay diversified, so, to go along with China’s rising per capita incomes and rise as a global power, it looks likely that the CNY will play more of a role in global reserve portfolios. For now, the CNY is a relatively small portion at only a few percent.

At the same time, US policymakers shouldn’t fret about this change of reserves flowing into the CNY and other currencies.

For one, all currencies have a very long way to challenge the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Globally, we know that US dollars are 62 percent of FX reserves, 62 percent of international debt, 57 percent of global import invoicing, 43 percent of FX turnover, and 39 percent of global payments (the only category the euro is close in).

Second, the dollar is already strong and foreign inflows into USD exacerbates this issue. The process of reserve managers putting more into focus into the yuan will move slowly. Despite China’s status as the second largest economy in the world, it is still an emerging market in most respects – particularly as it pertains to the rule of law, style of government (i.e., where it is on the democratic / authoritarian spectrum), private property protection, and development of its capital markets.

China’s currency is still managed as covered earlier and is not used heavily in international transactions. So, it still has a long way to go, but from the US’s point of view, the globalization of the yuan should be welcomed.

What about global fiscal policy in reducing the dollar’s strength?

Fiscal policy in the US is relatively loose in comparison to its main trading partners.

This includes Germany, Switzerland, Norway, the Netherlands, and South Korea. Because the fiscal policies of these countries are relatively tight, this leaves a lower sovereign debt supply. Some of the money that could be going into these sovereign debt markets ends up going into Treasuries (i.e., the USD), adding to USD strength. And because of this lower spending by these governments, this holds down growth and nominal interest rates.

So, more fiscal expansion by fiscal surplus countries would help boost global growth to some extent and help slightly lower the value of the dollar. The issue is that deciding what to do with the fiscal budget is a political process, which means a lot of the onus to stimulate economies will continue to fall on central banks.

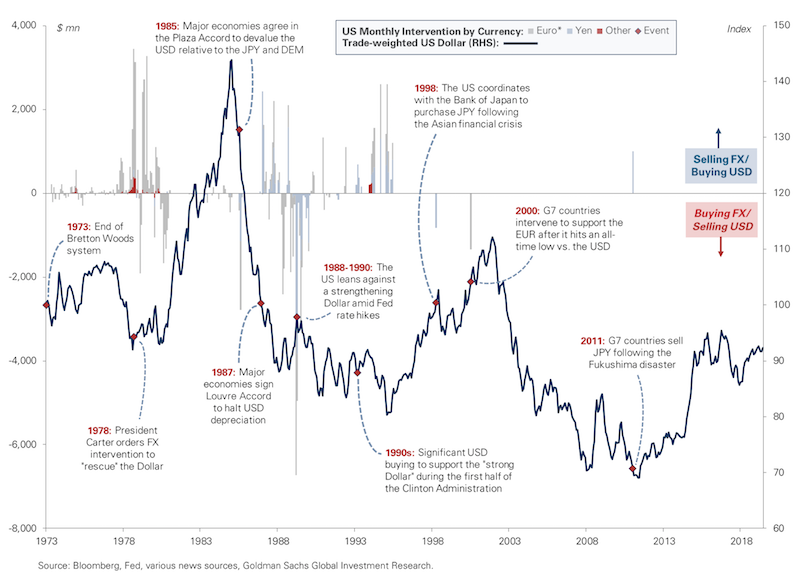

The Long History of FX Intervention in the US

Below is an annotated graph of all US invention efforts since the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971.

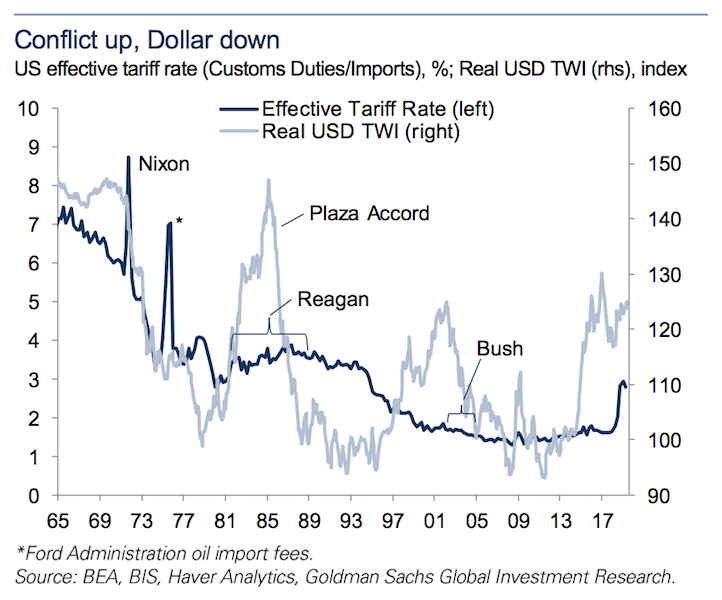

Can the current trade conflict help to weaken the dollar?

Today, trade conflicts are uncommon. Nonetheless, trade disputes have not been uncommon historically even in modern times. Prior US administrations have resorted to protectionist measures, or threatened using them, to achieve trade-related policy goals. This has also come with consequences for foreign exchange markets.

Can the US-China trade conflict influence a weaker dollar, as it’s done in prior US trade disputes?

In total, there have been three periods of trade conflict in the US over the past half-century.

When the US went off the gold standard in August 1971 – which sent the USD down by itself – the Nixon administration levied a 10 percent surcharge on all US imports. At the time, the Japanese yen and many European currencies were weak relative to the USD.

In the 1980s, the Reagan administration used tariffs and other trade measures directed at Japan to help reduce the bilateral deficit between the two countries.

In the mid-00s, the Bush administration, as well as members from both parties of Congress, were concerned about China’s tactical devaluation of the yuan and threatened tariffs on China.

Over time, the US tariff rate has gone down, until Trump came in office and used tariffs as a way to draw concessions out of China with respect to trade balances, IP theft, market access for US companies, coerced tech transfer, government subsidies, and related issues.

While many perceive the current trade conflict as merely a Trump-driven phenomenon, all these previous situations had the same basic circumstances in place. There were underlying macroeconomic motivations related to balance of payments deficits aggravated by an overvalued USD and its consequent influence in the loss of global trade competitiveness. This came with both aggregate and distributional implications for the US economy.

So, the trade conflicts would have likely happened anyway irrespective of whoever the president or other political personnel happen to be.

Eventually, dollar weakness helped to assuage these previous episodes of conflict and help stabilize the US trade account.

Moreover, the dollar did not weaken in these cases purely due to free market forces. Largely, this came due to settlements negotiated directly with US trade partners. In 1971, there was the Smithsonian Agreement; in 1985 came the Plaza Accord; and in 2005-06, there was a period of diplomacy with China.

Namely, all three periods saw the US lob protectionist measures (or threats thereof) on its trade partners before eventual resolution through their willingness to revalue the exchange rate to “fairer” levels. When the trade balance began to improve (i.e., deficits became less negative), these tariffs (or threatened tariffs) were typically removed.

The Trump administration’s take on US trade policy

While it is true that Trump is more willing to take on trade issues directly than other politicians, there are still macroeconomic realities underlying these measures.

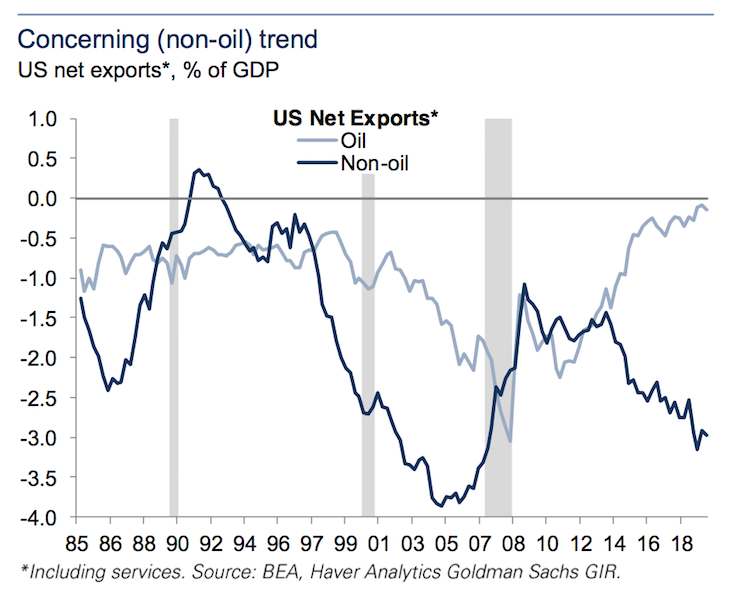

For one, a strong USD is hurting manufacturers and farmers’ competitiveness globally.

The non-oil trade balance is now minus-3.0 percent of GDP, which is high and unsustainable.

This has distributional impacts in the US, such as the upper Midwest, where the local economies depend more on farming and/or manufacturing. The political strategy and goals surrounding US trade policy may depend on who’s in the White House, but the underlying macroeconomic influences driving the current conflict are the same irrespective of the administration.

Conclusion

A ‘currency war’ is a potential tail risk. Having it set off through an escalation in the US-China trade conflict is one way it could come about, but that is unlikely.

Instead, tit-for-tat currency devaluations are most likely to become a theme in the next global recession. Throughout the developed world, interest rates are at zero or just above zero from the front-end of the yield curve to many years out. That means the primary form of monetary policy (adjusting front-end interest rates) won’t be available and secondary monetary policy (quantitative easing, or adjusting rates on the longer end) won’t be there either if those spreads are already down at zero or negative. In the US they are still positive, but they are no longer at 5 percent or higher as they were before the last recession, so there’s only so much further QE can go.

When rates policy is out of room, economic moves get transmitted through the currency. This makes currency devaluations one of the next possible policy choices for policymakers.