Reserve Currency History, Status, and Benefits

In a separate article, we covered the current status of the basic reserves today; namely, the USD, EUR, JPY, GBP, CNY, and gold, as the main few.

In this article, we’ll cover reserve currency history as well as reserve currency status, the benefits it brings, and how it’s lost.

We are currently in a precarious period for the world’s top three reserve currencies (US dollar, euro, and yen), given their very low nominal and real interest rates.

By pushing the boundaries of sound money, the main reserve currency areas are working to extend their money and credit creation cycles while also threatening the special privilege that its status brings.

When reserve currency status is lost, it can have calamitous effects on markets, which we’ll explore later in the article.

What is a reserve currency?

A reserve currency is a currency that’s used and accepted globally for savings and transactions. The US, having the tremendous privilege of being able to create the world’s top reserve currency, is in a very powerful position.

The debt denominated in the world’s reserve currency (US Treasury bonds) is the basic foundation on which the world’s capital markets and economies are built.

The US 10-year is one of the world’s most followed financial benchmarks as a medium-duration interest rate in the world’s reserve currency (a bond is a promise to deliver money over time).

It’s nonetheless true that all reserve currencies stop being reserve currencies at one point or another. Typically, the loss of reserve status comes abruptly and traumatically to countries and empires that enjoyed the privilege.

This topic is especially important now because of where the United States is in its development arc. The US, by most accounts, appears to be in the initial decline phase where its share of global activity is declining and the costs of maintaining the empire exceed the revenue it brings in.

The interest rates provided on US cash and Treasury bonds are lower than inflation rates.

Moreover, the US has to keep creating money to plug its fiscal and current account deficits.

This gives the reduced incentive for both domestic and international entities to hold US dollar debt. This means they’re going to want to look for alternatives to the dollar and dollar-based assets.

This is especially true for dollar debt assets. Even as the US creates more of them because of its deficits, the rest of the world (and domestic US entities) will want less of them because the interest rate compensation is so low. In fact, it’s a penalty to hold many of them in real terms.

It requires a rethink of portfolio strategy given the dollar and dollar assets have been very strong for most everybody’s lives (since the end of World War II).

So, the case of whether the dollar will decline as a reserve currency – and when and why – will become important to consider going forward, with its implications for how it will change the world as we know it.

Reserve currency history

Over the past 300 years, there have been three major empires – the Dutch Empire, British Empire, and American Empire.

Each was characterized by having a reserve currency.

Generally, the empire that becomes the most dominant from having high levels of quality in each of the following seven factors will typically have a reserve currency:

- Education

- Competitiveness

- Technology

- Economic output

- Having a large share of world trade

- Military strength

- Having a strong financial center

Strengths or weaknesses in each of these areas tends to be mutually reinforcing.

For example, if a country doesn’t have strong education then it’s not likely to be globally competitive, produce technological innovations, have a lot of economic output, and so on.

Education has long been a leading indicator of a country’s success, while a reserve currency has long been a lagging indicator. For example, the US dollar is still dominant in the world’s currency system despite the weakening fundamentals of the USD.

The USD is more than 50 percent of global reserves despite the US accounting for only 20 percent of global economic output.

A reserve currency is similar to the ongoing popularity of languages

A common currency is akin to having a common language – it tends to stay around because it’s been habitually used for so long rather than the strengths that had made it so commonly used to begin with.

For example, Spanish is one of the most popular languages in the world because the Spanish empire spread its language to new parts of the world in the late-1400s through the 1600s when it was a dominant power. The language has outlasted Spain’s economic power with a long lag, as languages get passed from generation to generation.

English is very dominant globally – especially as a second language – because of the British empire and its dominance in the 1700s through the early part of the 20th century.

The American empire has continued this pattern. For instance, the US has had a big hand in developing the internet and English content is still a large percentage of the overall internet.

China is now catching up to the US in various respects. Though China had declined in relative power after 1800 (and especially so after 1850) it had been consistently powerful for centuries before then. However, it was never powerful at an international level and never established a global reserve currency.

But it takes a lot to kick into gear a change to the status quo in currency regimes. They become so embedded in the way business and transactions are done globally.

What brings about reserve currency status

The countries dominant in trade and capital flows will have their currency used as a medium of exchange globally. It can be used for invoicing purposes and it can be used as a store of value in the countries it does trade with.

This leads to a currency’s internationalization. The more it’s used for transactions and as a source of savings the more of a reserve currency it’ll become.

This is how the Dutch guilder became the world’s primary reserve currency when the Dutch were dominant in the 1600s to the mid-1700s.

Then the British pound then became dominant from the mid-1700s for the same reasons.

The US dollar became the world’s top reserve currency in 1944 when the US was on its way to winning World War II and was clearly the world’s most dominant power economically, financially, technologically, militarily, and geopolitically.

We discussed this in greater detail in The Past 500 Years of Financial History & The Impact on Today’s Portfolios.

A reserve currency gives greater borrowing and spending power. It also, as mentioned, comes with a significant lag relative to other fundamentals. Even after the initial relative decline of an empire, the power of a reserve currency commonly peaks around 20 to 80 years after.

That tends to give the richest and most powerful countries the ability to borrow more money. This tends to drive them deeper into debt.

It’s not a coincidence that the main three reserve currency parts of the globe – the US, Europe, and Japan – are also the most deeply indebted relative to their incomes and are issuing debt at negative real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. Sometimes the rates offered on the debt are even negative in nominal terms.

The issuance of debt increases these countries’ spending power over the short run but weakens it over the long run.

Just like with a company or an individual, when a government is borrowing and spending a lot, it appears strong when in fact its finances are being weakened as a result of this behavior.

Governments are just a collection of people. They are not rich entities. When governments are issuing debt and “printing” money to finance its spending, most everyone cheers this along and wants the government to do more of it.

After all, if one is the recipient of this money and credit and one’s wealth appears to be increasing as financial and investment asset prices go up as measured in the depreciating currency, then it seems like a good thing and it feels good.

But there’s not any acknowledgment that the government doesn’t have the money and credit it’s giving out. It’s borrowed money. And that eventually has to be paid back.

That borrowing enables a country to sustain its power beyond its fundamentals because it finances domestic consumption (i.e., over-consumption) and the military spending and/or wars required to maintain the empire.

The borrowing can keep going for a while. It can even be self-reinforcing, helping to strengthen the reserve currency and increase the returns of international creditors who are lending in it. But it doesn’t last forever.

Signs of relative wealth shifts

When richer entities start borrowing from poorer entities, it’s an early sign that a relative wealth shift is going on.

For instance, in the 1980s, US per-capita income was around 50x that of China (depending on where exactly in the decade you measured it). It was at this point that the US started borrowing from China.

China wanted to save in US dollars and build up its repository of national savings in USD (and other reserve currencies) because it was the world’s primary reserve currency.

This was an early sign of China’s ascent in the world pecking order.

This has gone on in various other examples throughout history.

During World War II, the British borrowed money from its colonies to help finance its war spending.

The Dutch did the same thing before their relative decline.

In both cases, this led to declines in their currencies, debt markets, and real economies when the willingness to hold their debt declined.

The US has done a lot of borrowing and also monetization of its debt where the central bank buys it (also known as “quantitative easing” or asset buying). This hasn’t yet materially reduced demand for US dollar and US Treasury bonds.

We are now some eight decades past World War II and debt monetization is being used in each of the three main reserve currency areas (it was first used in Japan).

This is because there are large debts relative to output and traditional monetary policy doesn’t work very well in stimulating more money and credit creation as a means to stimulate productivity growth.

At the beginning of the decade, the world dealt with an economic downturn and debt contraction. This produced big drops in income and blew large holes in the balance sheets for individuals, companies, non-profits, and local and central governments.

Governments with the capacity to print money and provide credit had to come in to fill in these holes for these entities by monetizing debt.

At the same time, all of this had to be done at a point where there are large gaps in values and wealth between various elements of society. And there’s the rise of China coming up to challenge the US and its Western allies to become the leading global power in various forms:

- Trade

- Economics and capital markets

- Technology

- Military armament

- Geopolitics

Currently, the US dollar accounts for around 55 percent of all financial transactions and generally 50 to 60 percent share in the main categories (i.e., invoicing, foreign exchange reserves, international debt).

The euro accounts for around 25 percent of all global transactions. While it’s in second behind the dollar, it is considered much less important to the international payments system.

The Japanese yen and British pound account for around five percent each.

The renminbi (aka the yuan) is smaller at around two percent. But it’s growing quickly as China takes an increasing share of global economic activity and is already has the largest share of global trade.

Having a reserve currency is a double-edged sword

While having a reserve currency is great because it gives tremendous borrowing and spending power, it also causes a country or empire to over-borrow and eventually leads to the loss of reserve status and its relative decline.

A reserve currency leads to cheaper borrowing costs, which naturally leads to more borrowing. This leads to having too much debt that can’t be paid back.

The central bank then needs to create a lot of money and new credit to make up the difference, which devalues the currency.

As a currency devalues, fewer people want to hold it as a source of savings and income.

Countries that have reserve currencies have the leeway to create a lot of them when there’s a shortage of them. The 2008 and 2020 scenarios were good examples.

A global downturn created a need for dollars to service debt. In addition, international trade slowed, which is one of the primary ways that dollars circulate globally.

But countries that don’t have reserve currencies find themselves in positions where they can’t create a lot of money and credit because there’s a lack of demand for it.

They find themselves in need of reserve currencies like dollars when:

i) they lack savings in those currencies

ii) they owe money in currencies they don’t have the ability to print

iii) their ability to earn money in those currencies falls

Countries that don’t have them can find themselves in a bind when they need to pay their debts in those currencies or when they need to buy things (e.g., standard imports) from sellers who invoice in reserve currencies.

It can strain their finances to the point of bankruptcy. This was the situation many countries found themselves in in 2008 and 2020 as well.

It is also true for many local governments in the United States.

They have large debts and other cash flow-driven liabilities that are coming due (mostly related to pensions, healthcare, and insurance liabilities) that can’t be funded and will require money or loans from the federal government or through municipal financing.

Every time an economic downturn comes, many entities (local government, companies, nonprofits, households) will find themselves with low savings relative to their losses.

This forces them to either cut expenses down to the revenue they have or they have to get money and/or credit from another source.

Some entities will get money or inexpensive credit that may not have to be repaid. (If a loan has a zero percent interest rate and goes on forever, then it’s essentially like being given money.)

The free market will largely not be the allocator in these situations. It will be the central government that determines who receives the money and credit and who doesn’t.

Taking a reserve currency too far

The excessive creation of fiat currency leads to a selling of debt assets, which can create a self-reinforcing dynamic.

Losses suffered on assets that were believed to be deemed safe may come as a shock to some because they’ve been safe for practically their entire lives or memories.

When they’re less safe than believed, this can exacerbate the selling.

The central bank can’t allow yields to rise above a certain level (which is what occurs when the prices of these debt assets fall). So they naturally want to print money and buy the debt to keep yields under control.

This, in turn, causes the value of money and credit to further diminish, causing people to want to get out of the currency and bonds.

They decide what alternative store of value this might mean.

Classically, it’s something like:

- gold and to a lesser extent silver

- foreign currencies with better fundamentals (or less worse than the currency having problems)

- stocks and businesses that will retain their value in real terms

- collectibles, and

- certain types of commodities

It comes down to what’s believed to be a store of value.

There doesn’t necessarily need to be a different or new alternative reserve currency to move toward.

There have been cases where there was no great alternate currency to go to, such as the fall of the Roman Empire and several cases of the declines of various dynasties in China.

There is a vast trove of assets and things that people will turn to when currency and debt in that currency is devalued.

In Germany’s Weimar Republic in the 1920s – the most famous case of hyperinflation – people even turned to machinery and stones as a store of value as the inflation became incredibly bad.

Social gaps

The loss of a reserve currency also generally comes with domestic social conflict and is commonly associated with very low nominal and real interest rates.

The lowering of interest rates benefits investors and capitalists at the expense of savers and those who don’t own financial assets.

So there are typically large wealth gaps that come about as a result of these policies (even though the good typically outweighs the bad). As a result, more perceive the system to be unfair.

There’s also likely to be values gaps and more fighting politically between the left and the right. Those who have wealth tend to want to move more of their wealth to physical, “hard” assets and other countries and currencies.

Policymakers don’t like this because it makes their policy measures less effective when capital is leaving the country or jurisdiction they have control over.

Banning alternatives

Typically, policymakers want to make it harder to own alternative assets. Gold is the classic alternative. With some exceptions (e.g., jewelry, collectors coins), it was banned in the United States in 1933. This lasted officially until 1975, with some restrictions repealed in 1964.

They generally don’t want foreign currencies to exist and don’t allow transactions in them. Foreign exchange controls (i.e., capital controls) are also common to prevent money from leaving the country.

When there is geopolitical conflict with a country, this also increases the odds of “enemy currencies” being banned. Or there are strict limitations.

Russia doing this with the US dollar in 2022 is an example because of the sanctions the West levied upon Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. (See: Best Assets to Own During a War Economy)

Debt is eventually mostly wiped out by creating a lot of money to make it cheap, which devalues the money and debt.

When this is taken to an extreme, the money and credit system is destabilized and breaks down. Debts have effectively been devalued or defaulted on.

Generally, there’s a need to go back to a currency with a hard backing to it to help restore people’s faith in the value of money. This enables credit growth to resume.

The hard backing is commonly gold or a reserve currency – pegged to it or using it directly (e.g., Ecuador’s dollarization of their economy in 2000). Holders of the money can convert it into a certain amount of gold or the reserve currency.

This link to a hard currency or asset is common, but is not a prerequisite.

In sum, in the early stages of having a reserve currency, holding debt as an asset is generally rewarding. It provides interest and there isn’t a lot of debt outstanding.

But later in the cycle owning debt assets is riskier. There’s more of it, and because there’s a lot, governments have to keep the rates on it lower to accommodate the debt load. It’s at this point that it’s closer to being devalued or defaulted on.

For example, in the US, as the debt load relative to income has increased each cyclical peak and each cyclical trough in the interest rate cycle has been lower than the previous one.

This led to hard landings in 2008 and 2020.

US short-term interest rates

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

And after each hard landing, there isn’t much lift-off because the level of indebtedness prevents it.

In Q4 2018, 10 years after reducing interest rates to zero to help alleviate the debt crunch, it could only hike them to a bit over two percent before a 20 percent drop in markets told them they were starting to break things.

Holding bonds is generally safe for a long period of time. But there come occasions where they become significantly devalued or defaulted on.

These cycles of debt and defaults have existed for millennia. In scripture, there are references to the wiping out of debt every 50 years (the year of Jubilee). Because of this schedule, people could prepare for it. Even in modern economies, devaluing debt or defaulting on it commonly occurs once every 50-100 years.

Being prepared for it rather than surprised is the goal of any trader or investor. When there are:

- very low nominal rates (around zero) on currency and bonds

- negative real rates

- large fiscal and trade deficits, and

- the central bank is monetizing debt (buying its own debt)…

…it’s typically a sign that currency (cash) and bonds are poor assets to hold.

Having enough for safety, liquidity, and some level of diversification is helpful, but they are bad from a return standpoint.

Naturally, because this cycle is so long, what most experience is the main factor that dictates the decisions they make. Those who are closer to the “blow up” tend to feel the safest.

This is due to the fact that they’ve held the debt and enjoyed the benefits of doing so for a long time since the last blow up.

Accordingly, the memories of the last big devaluation or default fade and they become more comfortable even as the risks of holding it increase as debts pile up and the rates paid on holding it fall.

How to determine the risks and rewards of holding money and debt assets

There are three main criteria to determining whether debt is worth holding:

- The amount of debt that has to be paid relative to the cash flow available to service the debt.

- The amount of debt that has to be paid relative to the amount of earned money (different from “printed” money) available to pay it.

- The interest that’s to be paid for lending one’s money. Higher rates are required for riskier borrowers.

Many debt restructurings are generally needed to break the monetary system

Debt crises are rectified in four main ways, through a combination of austerity, wealth transfers, money printing, and debt restructuring and write-downs.

Austerity and wealth transfers are painful and limiting

Austerity and wealth transfers are typically not big contributors.

Austerity is painful. It’s often done in countries that lack reserve currencies.

But it’s not politically acceptable to cut expenses down to revenue and harm incomes and spending in that way. This is especially true if a country has a reserve currency and can print their way out.

Wealth transfers – such as taxing those that have more to give to those who have less – is also hard to do beyond a point.

In many debt crises, the incomes of those at the top are severely dented and capital markets perform poorly, especially when the crisis is most intense. (How fast they recover depends on the speed and level of the policy response.)

This reduces employment in an economy and curtails the amount of taxes that can be collected.

Money printing and debt restructurings are most common

So, a combination of money printing and debt restructuring is the go-to plan in reserve currency debt crises. Money printing is inflationary; debt restructuring is deflationary.

The two can be balanced against each other where the loss of credit can be offset through money printing in the right amounts to reduce the debt burden and avoid deflation.

Restructurings tend to last for short periods of time, generally months to a few years depending on how fast governments act.

Restructurings can be done through a combination of:

- writing down how much needs to be paid (e.g., paying 50-80 percent instead of all of it)

- changing the interest rates on it to make debt servicing easier

- changing the maturities so it can be spread out over time to make payments easier

- changing whose balance sheet it’s on (government printing money and buying debt to save systemically important entities)

But sometimes reserve currencies can stop being reserve currencies if too much money needs to be printed and/or the interest rates offered on the currency and bonds is too low.

It generally takes more than one debt or banking crisis and write-downs or devaluations to break a currency and credit system. Oftentimes, there are multiple currency depreciations and debt write-downs of 30 to 40 percent or more before a system is broken.

The US went through big devaluations in 1933 and 1971 – back when the dollar was on the gold standard – and did not lose its reserve status.

2008 and 2020 were similar crisis circumstances. But they didn’t have the same “big break” characteristics of the 1933 and 1971 events because exchange rates were free-floating rather than linked to gold.

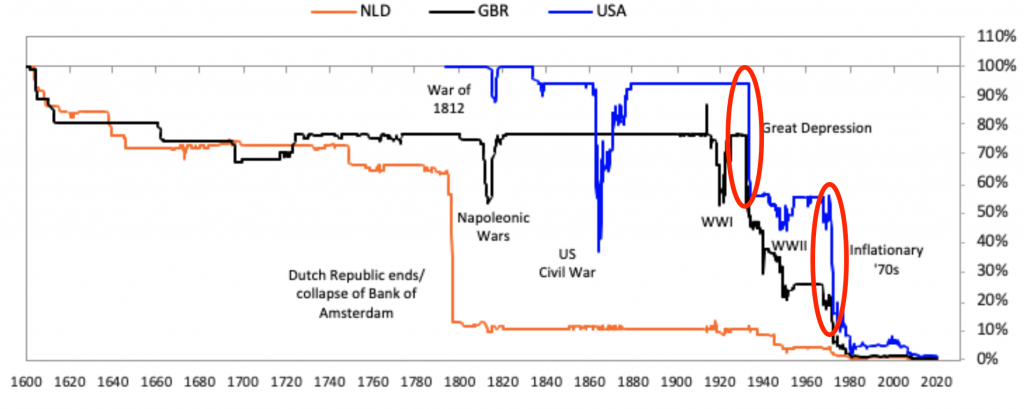

Dutch guilder, British pound, and US dollar devaluations relative to gold (1600-present)

Having the world’s leading reserve currency has been vital to the US sustaining and extending its power.

Being a great power depends heavily on being able to create money and credit in a currency that’s broadly accepted throughout the world as a medium of exchange and store of value.

Having the ability to print the “world’s currency” is instrumental in keeping the US’s relative financial power at multiples of the size of its actual economic power.

It’s an exorbitant privilege that is largely taken for granted and also being abused for reasons that aren’t surprising.

Since 1944

Since the end of World War II in 1945, the US has been the world’s most dominant power. The Bretton Woods agreement put the dollar in the position of being the world’s top reserve currency the year before.

The US and its currency fit naturally into the role. By the end of WWII, the US had around 70 percent of the world’s gold held by governments. Gold was considered money then.

It had around half of the world’s economic production and was the top military power based on conventional forces and had a monopoly on nuclear weapons until the Soviet Union caught up in the 1950s and 60s.

The monetary system was linked to gold. Paper money could be exchanged for the precious yellow metal for $35 per ounce.

Gold was also made illegal to own back in 1933 at the depth of the Great Depression. Policymakers didn’t want gold to compete with US currency and credit as a store of value.

Paper money was considered analogous to a check that could be exchanged for the real money in gold.

But all US dollars were not backed by gold. There was $50 worth of paper money in circulation for each ounce of gold, or a bit over 40 percent more currency relative to what would be required to have full backing.

US allies (the Commonwealth countries, France, and the UK) or countries under US control that had lost WWII (Japan, Germany, Italy) had currencies that were linked to the dollar and effectively controlled by the US.

After WWII, the US government spent more than its revenue to finance its spending. This created more dollar-denominated debt.

Because of this, the Federal Reserve enabled there to be the creation of a lot more claims on gold (money and credit denominated in USD) than could be realistically converted into gold at $35 per ounce.

As paper money was converted into gold, the amount of gold reserves diminished at the same time claims continued to increase.

As is the case with many pegged systems, the “shadow valuation” or black market valuation climbed above the official valuation.

To satisfy all the claims, gold needed to be valued materially higher. And to this day, gold is valued as a type of inverse money, priced in relation to the value of the money used to buy.

Shrewd people at the time (in the years before the link was disbanded) bought gold in the ways they could, recognizing the unsustainability of what was going on.

The Bretton Woods system eventually broke down after just over a quarter-century in use on August 15, 1971.

In a similar announcement on March 5, 1933, the US defaulted on its promise to enable paper money to be converted into gold.

Therefore, the dollar was devalued against gold and against other currencies. It essentially made the dollar a fiat currency system.

This gave the Federal Reserve and other central banks the latitude to create a lot of USD-denominated money and credit. This led to the inflationary 1970s. (In the 1930s breaking the link simply offset deflation associated with the debt crunch in 1929.)

Gold and commodities did well; stocks and bonds poorly

Gold and commodities performed well in this environment. Stocks and bonds did poorly in inflation-adjusted terms.

Money fled from dollar currency and dollar-denominated debt to goods, services, and assets like gold.

The flight out of dollars and dollar debt caused interest rates to rise. Gold went from the $35 price it was pegged at from 1944 to 1971 (in the official market) to $670 by 1980, a rise of nearly 20x in less than a decade.

With the way monetary policy was being managed, it was profitable to borrow USD and convert it into goods and services, leading to inflation in the real economy.

Many countries did this, borrowing money from US banks and dollar debt grew rapidly throughout the world.

Banks made money doing this, but this led to a debt bubble. The flight out of dollars and USD debt assets and into goods, services, and inflation-hedge assets accelerated.

This came to a head in the latter part of the 1970s and early 1980s.

While most citizens didn’t have a good understanding of what was going on in terms of the monetary mechanics, they felt the pinch through high inflation and high nominal interest rates.

So, naturally it became a big political problem. It cost President Carter his second term and gave way to Ronald Reagan.

It characterized a period where the private sector took over a greater role over the management of the economy relative to the government. This largely went on until the crash of 2008.

Before exiting, Carter appointed Paul Volcker to head the Federal Reserve. Volcker was a strong enough personality to do the difficult and unpopular but necessary things to break inflation.

Short-term interest rates sat in the low-4 percent range as late as early-1977, but were eventually hiked to north of 15 percent on three different occasions to get inflation under control.

Short-term interest rates in the US fro 1969 to 1982

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

It caused two recessions in the process but worked.

How to deal with monetary inflation

Raising interest rates works to tighten the money supply and makes borrowing less attractive. Less money and credit gets spent, reducing inflation.

This typically hits financial markets first – especially if they’re not adequately prepared based on what’s discounted in. Then it hits the real economy as those new rates work their way through and alter incentives.

The nominal interest rate that the Fed hiked to in March and December 1980 and May 1981 was well above the inflation rate.

This meant that borrowers had to pay more in debt service at the same time their incomes and the value of their assets fell.

Debtors had to sell assets to meet their payments.

It also meant there was a need for dollars. This caused the dollar to be strong.

A currency can be strong even as an economy is weak for this reason. Each market (money and credit + goods and services) has different supply and demand factors related to them.

Inflation rates fell as rates were hiked. This enabled the Fed to lower interest rates once inflation was no longer a problem. And because of the inflows into the dollar, interest rates could be lowered without triggering inflation.

But naturally many debtors and holders of financial assets disadvantaged by this policy went broke.

Foreign debtors, especially those in emerging countries, were the most hurt of any category. These countries went through a difficult period of debt restructurings and poor growth that took years to recover from.

The Fed extended loans to US banks to make up for the shortfall in income they would be experiencing.

Moreover, accounting standards at the time didn’t require them to mark those bad loans as losses or require them to mark down those debt assets to their true prices.

This enabled them to raise capital at higher prices they would have been able to otherwise.

In combination with the bridge lending they received, this allowed American banks to pretend that everything was otherwise okay. There would be no debt crunch, as getting rid of the bad loans could be spread out over many years if new loans replaced them.

August 1982 was the bottom of the stock market and enjoyed an unprecedented run until the dot-com bubblen burst in 2000.

This process of writing down and restructuring debt went on until 1991. US Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady eventually completed it through what’s known as the Brady Bond agreement, which had maturities of up to 30 years.

The 1971 to 1991 period affected many people around the world, and was a direct result of the US taking its currency off the gold standard.

The initial abandonment of the gold standard led to lots of money and credit creation, high inflation, and outflows into inflation-hedge assets.

It was followed by a consequent tightening in policy and debt restructuring by non-US debtors. Inflation rates fell and led to a strong bull market in bonds, debt assets, and stocks in the 1980s.

The reverberations were a forceful display of the US’s power from having the world’s top reserve currency and the implications for people around the world of how a reserve currency is managed.

2008

2008, like 1929, was another one of those rare periods where a debt crisis caused short-term interest rates to hit zero. And that drop in interest rates wasn’t adequate enough to create the money and credit expansion required.

So central banks needed to create money and buy financial assets.

The primary form of monetary policy is adjustments of short-term interest rates. When interest rates hit around zero or a bit below, that approach is no longer effective.

So they turn to the secondary form of monetary policy, which is money creation and the buying of financial assets.

The buying starts with mostly government bonds and government-backed securities (like mortgages). Then it goes into high-quality corporate debt and down the quality ladder from there. It can also go all the way into riskier assets depending on how far they need to go.

Asset buying occurred in 1933 when interest rates hit zero and continued through World War II to keep short-term and long-term interest rates fixed to finance the large deficits. It was essentially yield curve control.

This is currently called “quantitative easing”. It’s a less unnerving term than “debt monetization”.

All the main reserve currency central banks did this in 2008. It was necessary to keep the money and credit expansion cycle going.

Buying assets increased the price of bonds, bringing their yields lower, and giving the sellers of those bonds cash to go buy other things (mostly other financial assets of slightly riskier characteristics).

This, in turn, pushed up the prices of other assets and increased net worths and creditworthiness.

It also decreased forward expected returns. Bond yields fell to very low levels, as did the future returns of stocks.

Pension funds and many other types of investors would no longer be able to fund their various spending obligations over the long run.

This created incentives to lever up to buy assets that they expected to have higher returns than the rate at which they were borrowing.

As such, you can see that while these policies are a good thing – i.e., using a reserve currency to correct debt and imbalances – it can easily create a different type of issue with asset bubbles.

Asset bubbles are fueled by a new different type of debt bubble.

Bubbles pop when the returns the assets offer are less than their funding costs.

It can facilitate a large boom but also a large bust when they get stretched too far.

The disproportionate effects of a reserve currency globally

Reserve currencies are good for the countries that can create them. But they might often not provide much benefit to those who are not citizens of these countries.

In 2008 and 2020, the Federal Reserve was in the position to run monetary policy that was good for Americans. The US Treasury decided to borrow money and new credit and give it to Americans.

The Fed bought a lot of the debt that came out of that and existing debt to help Americans through the crises. Little of that went to foreign entities.

For many Europeans, the ECB was a major force. The Bank of Japan, an even smaller bank, did the same for the Japanese. The PBOC could help China to the extent it was needed. Other smaller banks (e.g., England, Switzerland, Canada, Australia) could also do something for their own citizens.

But most of the world was shut out from getting money and credit to fill in their income and savings gaps the way Americans could because the US had the power to do so much of it.

This is similar to the aforementioned period of 1981-1991 period for a lot of Latin American countries that borrowed in dollars.

But the major difference is that interest rates could be cut significantly more in 1981-1991 (anywhere from 6 to 20 percentage points worth of room). Now they can be cut negligibly.

The USD as the world’s primary reserve currency, and having the world’s most prominent central bank that can create the currency, can put those dollars in the hands of Americans (and others if it chooses to) more effectively than most other central governments can help their own citizens.

At the same time, doing so risks losing this privilege by creating too much money and debt.

Relative per-capita GDP effects associated with a top reserve currency

Generally, the country with the world’s top reserve currency enjoys a 20-25 percent improvement in per-capita GDP as a result of having this privilege.

This is due to the enormous borrowing and spending power it brings on. That borrowing and spending feed into incomes.

For example, the US has about a 20-25 percent advantage in per-capita incomes relative to most developed European countries, Japan, Canada, and developed Oceania (Australia, New Zealand).

Japan came within about 10 percent of the US during the peak of its asset bubble in the late 1980s as a result of the overspending that occurred during this period.

But this advantage has held true since the US established its own currency as the world’s top reserve currency as part of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1944 when it was looking increasingly clear that it would win World War II.

When a country wins a major war and is clearly the world’s most dominant power, it gets to effectively write the rules.

And to be clear, the US does not have the highest per-capita GDP in the world, and per-capita incomes are influenced by a wider set of factors than reserve currency status.

But the data is skewed by idiosyncratic outliers.

For example:

- oil and gas rich nations (Qatar, Norway, Kuwait, Brunei, UAE)

- tax havens (Ireland, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Macau, Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland), and

- micro-states (Liechtenstein, Monaco, Luxembourg)

These factors are different and aren’t appropriate to use when evaluating the wealth effect of relative reserve currency status.

Losing reserve currency status

The main three reserve currencies globally – the US dollar, euro, and yen – are pressing up against the constraints of how far the money and credit creation process can go on.

We know this based on where their interest rates are on short- and long-term debt (close to zero).

Debts denominated in them are:

- high relative to incomes

- with low incentives to holding this money and credit – i.e., low real interest rates paid on them

- and large amounts of new debt are being created in them and being purchased by central banks because there’s a lack of free-market demand (i.e., monetized)

This is creating a riskier scenario that can set the stage for large devaluations and/or a loss of reserve currency status, which would be one of the more disruptive financial and economic events one could imagine.

We are, however, less likely to see “big breaks” as we’re now in a free-floating monetary system. There have been more continuous and gradual devaluations as opposed to sudden and episodic.

Since 2000, the value of money of most reserve currencies has fallen in relation to gold due to the level of money and credit creation and because interest rates have been low relative to inflation (though even as inflation has been low as well).

Patterns of devaluation and loss of reserve currency status

Large currency devaluations and loss of reserve status are caused by the same things (too much debt) but aren’t always the same thing.

Loss of reserve status comes from large and repeated devaluations. Creating money and credit to offset shortfalls reduces the value of money and credit.

This creates relief to those who need more money to relieve their debt issues. But it’s bad for the holders of the currency and debt assets (mostly bondholders and lenders of fixed-rate debt).

When the creation of money and credit helps facilitate productivity and profits, real equity prices increase. Like any form of credit creation, it’s useful if it pays for itself (revenues exceed costs).

At the same time, if the yields of cash and debt assets are driven low enough, it can drive people out of those assets into other types of non-credit assets and other currencies.

This leaves central banks in a position to either allow real interest rates to rise (which hurts economic output) or prevent rates from increasing by printing money and buying bonds and other assets to keep yields down.

They always prefer to do the latter. Of course, this only causes more of the poor actual and prospective returns of holding cash and debt assets.

When interest rates get pressed down so close to zero (or into negative territory) that it becomes difficult to press them down further, it becomes increasingly likely that there will be a break in the currency and credit system.

But there’s a difference between devaluations that are systemically threatening or destructive and ones that are beneficial and allow for a continuation of the money and credit creation cycle.

When Did All the Major Currencies Come into Existence?

The creation of major currencies has a widely varied timeline, each deeply intertwined with the socioeconomic and political histories of their respective nations.

Below is a brief overview of when some of the major currencies came into existence:

United States Dollar (USD)

- Year: 1792

- Context: Established by the Coinage Act of 1792.

Euro (EUR)

- Year: 1999 (for electronic transactions), 2002 (banknotes and coins)

- Context: Launched by the European Monetary Union.

British Pound Sterling (GBP)

- Year: 775

- Context: Originally introduced as sterling silver penny coins.

Japanese Yen (JPY)

- Year: 1871

- Context: Formally established with the New Currency Act.

Chinese Yuan Renminbi (CNY)

- Year: 1949

- Context: Introduced by the People’s Republic of China after the civil war.

Swiss Franc (CHF)

- Year: 1850

- Context: Introduced by the Swiss Federal Constitution.

Canadian Dollar (CAD)

- Year: 1858

- Context: Adopted to replace the Canadian pound.

Australian Dollar (AUD)

- Year: 1966

- Context: Replaced the Australian pound.

Indian Rupee (INR)

- Year: 1540

- Context: Sher Shah Suri introduced a silver currency called Rupiya.

Brazilian Real (BRL)

- Year: 1994

- Context: Introduced during a period of significant economic stabilization in Brazil.

FAQs – Reserve Currency History, Status, and Benefits

Can other countries’ actions impact another’s reserve currency status?

Yes, other countries’ actions can impact a nation’s reserve currency status. A reserve currency is a foreign currency held in significant quantities by governments and institutions as part of their foreign exchange reserves, so it naturally depends on these holdings.

Several factors can influence a nation’s reserve currency status, including the actions of other countries.

Here are a few ways this can happen:

Economic and political stability

If a country becomes more politically and economically stable, its currency may become more attractive as a reserve currency.

Conversely, if a country becomes less stable, its reserve currency status may be diminished.

Trade relations

Countries that have strong trade relationships with other nations may impact the demand for their currency, and subsequently, their reserve currency status.

For example, if a significant trading partner decides to move away from using a particular currency for international trade, it can lead to a decrease in demand for that currency and affect its reserve currency status.

Currency swaps and agreements

Central banks and governments may enter into currency swap agreements with other countries.

These agreements can impact the demand for a nation’s currency and influence its reserve currency status.

International institutions and agreements

International organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, may impact a nation’s reserve currency status.

For example, if the IMF includes a currency in its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, it may lead to an increase in demand for that currency, strengthening its reserve currency status.

Shifts in global economic power

If a country’s economy grows rapidly and becomes more influential on the global stage, its currency may become more attractive as a reserve currency.

Conversely, a decline in economic influence can reduce a nation’s reserve currency status.

Confidence in the currency

If other countries lose confidence in a nation’s currency due to factors such as high inflation, fiscal mismanagement, or political instability, they may reduce their holdings of that currency, affecting its reserve currency status.

Influence limitations

But exceptions exist in how far a country can bend its will against another.

For example, Russia sold a lot of its USD FX reserves for euros and yen after it annexed Crimea and the US imposed sanctions.

But it then hedged a lot of those euros and yen back into USD in forward markets, since it needs USD for global trade.

But by and large, “reserve status” is most heavily influenced by foreign FX reserve holdings, not balances used for trade invoicing purposes.

How has the dominant reserve currency changed throughout history?

Throughout history, the dominant reserve currency has changed several times, usually reflecting shifts in global economic power and influence.

Here’s a brief overview of the dominant reserve currencies in different periods:

15th to early 18th century

The Portuguese real, Spanish dollar, and Dutch guilder were dominant due to the economic influence of these countries during the Age of Exploration and the rise of European empires.

18th to mid-19th century

The British pound sterling emerged as the dominant reserve currency because of the United Kingdom’s industrial revolution and global influence through trade and its extensive colonial empire.

Mid-19th to early 20th century

The British pound sterling continued to dominate, but other currencies like the French franc and the German mark also gained prominence.

By the late-19th century and early-20th century, the dollar became more dominant due to the rise of the US.

By around 1900, the US empire was roughly on par with the British empire in terms of global influence.

Post-World War II to present

The US dollar has been the dominant reserve currency, supported by the Bretton Woods Agreement, which pegged other currencies to the US dollar (and the dollar to that of gold until 1971 when the link was unilaterally broken), and the strength of the US economy.

What are the benefits for a country of having its currency as a reserve currency?

There are several benefits for a country when its currency is considered a reserve currency:

Lower borrowing costs

Countries with reserve currencies can typically borrow at lower interest rates, as the demand for their currency is higher and investors perceive it as a safe and stable investment.

Greater global influence

Having a reserve currency can provide a nation with increased political and economic influence on the global stage, as other countries often hold and use their currency for international transactions.

Increased trade

A reserve currency can facilitate international trade and investment, as it is more widely accepted and used by other countries, reducing the need for currency conversions and associated costs.

Seigniorage

Seigniorage is the profit gained from the difference between the cost of producing money and its face value.

This can provide a significant source of revenue for the country’s central bank.

Currency stability

A reserve currency is typically more stable in value due to its widespread use and demand.

This stability can benefit the country’s economy by reducing exchange rate risks and promoting investment.

Import advantages

A country with a reserve currency can import goods and services more easily, as other countries are more likely to accept their currency in exchange for their products.

This can help reduce the cost of imports and support economic growth.

What is the oldest existing fiat currency?

The British Pound (GBP) is the oldest existing fiat currency, having been established in 775.

Conclusion

Empires rise and fall along with their currencies. The most successful ones establish reserve currencies.

The establishment of a top reserve currency typically comes after a war. In the post-conflict period there’s a backdrop of prosperity, peace, and productivity.

Credit is allocated well and done sustainably. Most debts are used productively where incomes are greater than the debt servicing payments. So most debts are paid back.

Businesses grow in value and domestic capital markets increase in value. Most individuals benefit from the prosperity.

However, they benefit disproportionately. This leads to excessive debt growth to finance speculative investments and excessive consumption.

The things that the debt goes into doesn’t throw off enough income to service the debt. This leads to the need for central banks to lower interest rates and provide more money and credit into the system.

This exacerbates wealth gaps because of where this money goes (financial assets) and more over-indebtedness.

This goes on until the amount of debt becomes so large that central banks can no longer push this money and credit creation cycle further because it can’t be self-funded.

Cash and bonds typically become bad to own.

This is because they yield less than the rate of inflation for domestic investors and the currency is declining at a rate faster than the interest rate compensation for international investors. Currency and bonds essentially become a source of wealth destruction in this environment.

Consequently, this produces large economic downturns that are made worse by the wealth and values gaps that classically exist. This leads to large social conflicts and, in turn, bleeds into political gaps and more fighting about what to do about the set of circumstances.

As a result, there is lots of money creation, big debt restructurings and painful write-offs (provides relief to one side but wipes out some or all the income for another).

Typically, there are shifts to the left politically. This leads to tax changes that typically try to increase the burdens on those who have high incomes and wealth to redistribute it to those who have less.

This creates vulnerabilities for the country financially, economically, and politically relative to rising powers, which are incentivized to exploit these vulnerabilities.

This commonly leads to wars in various forms (trade, capital, economics, technology, geopolitics, and potentially military confrontations).

Wars in turn help define who becomes dominant and who becomes submissive. It eventually produces a new global order based on these results.

The dominant power gets to set many of the rules and commonly has a reserve currency that will provide it great spending and borrowing advantages as long as it has it. The losing power, if it had a reserve currency, will typically see the traumatic loss of this advantage and its relative decline in the global pecking order.