Yield Curve Control: What It Is and Implications

Yield curve control has gone from more of an abstraction to a policy that many of the world’s most influential central banks are currently using or considering using.

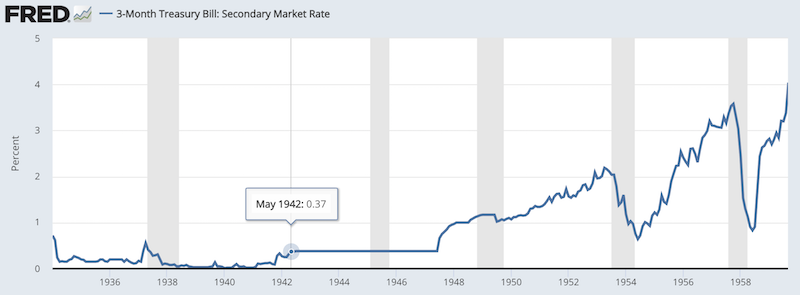

In the US, yield curve control, often known as YCC, hasn’t been employed since World War II.

Back then, the very high economic demands of WWII required capped funding rates to avoid US government debt – and eventual servicing requirements – from getting out of control.

From May 1942 to June 1947, short-term interest rates were held at 0.375 percent.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

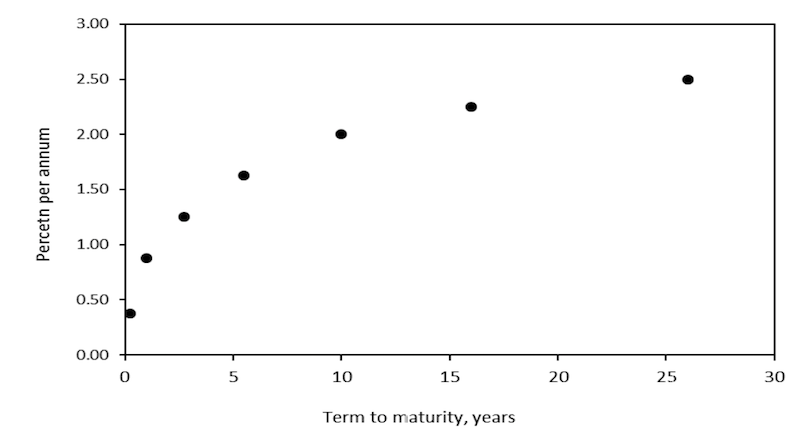

Intermediate yields included a 0.875 percent yield on 1-year bills, a 2 percent yield on 10-year notes, and a 2.25 percent yield on 16-year bonds. Yields of 2.5 percent were assigned to 31-year issues.

(Source: New York Federal Reserve)

The specific pattern of rates chosen was simply a matter of the financing rates that existed at the time they were implemented. As the country was still recovering from the economic malaise of the 1930s and Great Depression period, interest rates were already low.

There is no evidence of any attempt to identify market-clearing rates appropriate to a wartime economy. Nominal rates were kept fixed as a matter of policy irrespective of growth and inflation trends.

Under yield curve control policies, the central bank ensures low interest rates on borrowing many years into the future. The price of credit is set to a level that is close to the short-term interest rate, or cash rate, that the central bank is known for adjusting.

Yield curve control is often targeted at a certain maturity, such as the 10-year borrowing rate. Or it can be issued on a series of borrowing rates, such as debt issuances that span from three years to twenty years, for example.

In contemporary cases (e.g., Japan, Australia, the US), yield curve control has been targeted (or considered) at a single maturity in the three- to ten-year range. In other words, in additional to controlling the short-term interest rate, the central bank will also take over a longer term rate.

YCC vs. QE

Central banks can also influence interest rates through quantitative easing (QE), or the purchase of longer dated government securities (and sometimes non-government bonds, such as corporate debt and ETFs) to lower longer term interest rates.

QE is a secondary form of monetary policy when the adjustment of short-term interest rates is no longer effective.

The different between QE and YCC is that QE has no specific bond yield target in mind.

With QE, the central bank will commit to purchasing a certain amount of bonds or securities to support asset prices and that positive feed-through into the economy.

Yield curve control has a specific bond yield in mind. It will make the purchases it needs in order to effectively guarantee the yield rather than simply being an influence on them.

This ensures that large government deficits can be financed without interest rates going up.

QE will take a policy approach that commonly works by buying a certain amount of securities per month. YCC, on the other hand, will operate by coming into the market automatically as needed to buy or sell a certain amount of securities to maintain a specific yield.

Naturally, as debt issuance increases, investors are less likely to buy it. More debt supply can have an effect on creditworthiness.

Moreover, in terms of basic economics, more supply in relation to demand lowers prices. A lower price raises the yield. Price and yield vary inversely.

That said, the commitment needs to be credible. Buying an “infinite” amount of bonds to guarantee an interest rate isn’t free.

The pressure comes through either the interest rate side or the currency side. Since the interest rate is essentially pegged, that means it’ll have to go through the currency.

If a country has reserve status, it can “print” money to buy the bonds more than a country that lacks it.

Reserve status is largely a function of how much borrowing is done in a currency internationally. If there is widespread use and borrowing of a currency, that helps support demand for it globally.

If there’s global demand for a currency, then issuing more of it isn’t likely to lead to interest rate, currency, or balance of payments problems.

Under yield curve control, the money printing requirements are often significant in order to purchase enough bonds to meet the target as well as ensure enough liquidity to support the private sector and prices of risk assets.

Bonds that are effectively pegged would make the asset class very different from the ones that traders are accustomed to.

Historical vs. contemporary cases

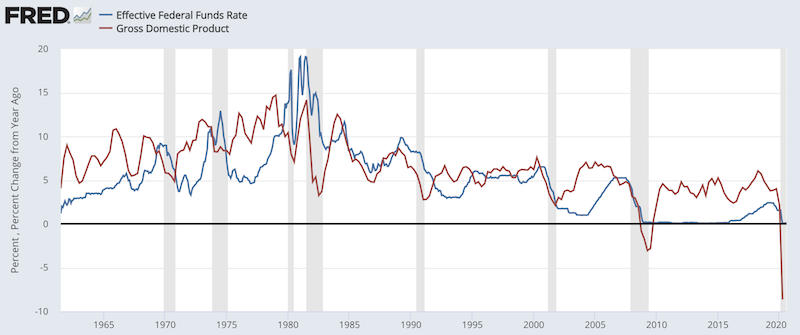

Since the WWII period in the US, markets have grown accustomed to bonds responding to shifts in expected growth and inflation.

Periods of higher nominal growth expectations (nominal growth is the sum of real growth and inflation) have corresponded to higher bond yields and lower nominal growth periods have corresponded to lower bond yields.

Nominal growth needs to be higher than nominal interest rates otherwise debt will compound faster than the economy grows. Accordingly, you can see throughout time that nominal growth has usually exceeded short-term debt yields.

(Sources: BEA, Board of Governors)

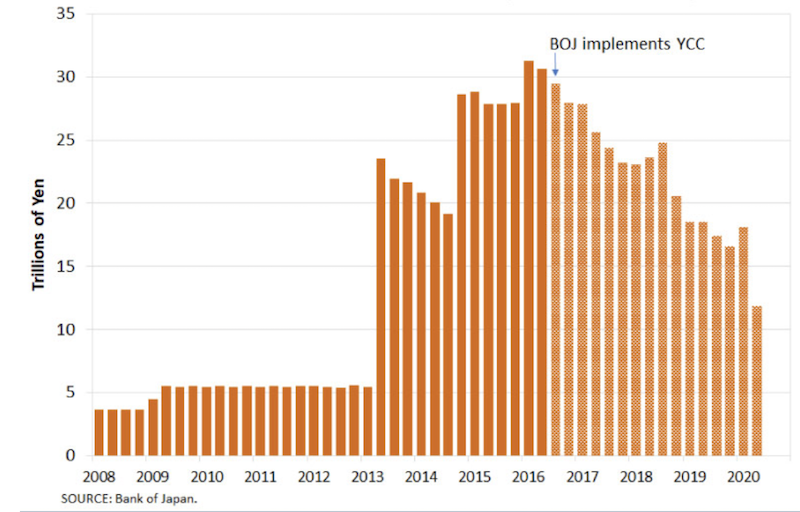

The Bank of Japan has used YCC since 2016. Its cash rate was already at minus-10bps, with the 10-year yield targeted at zero, giving a steepness of just 10bps.

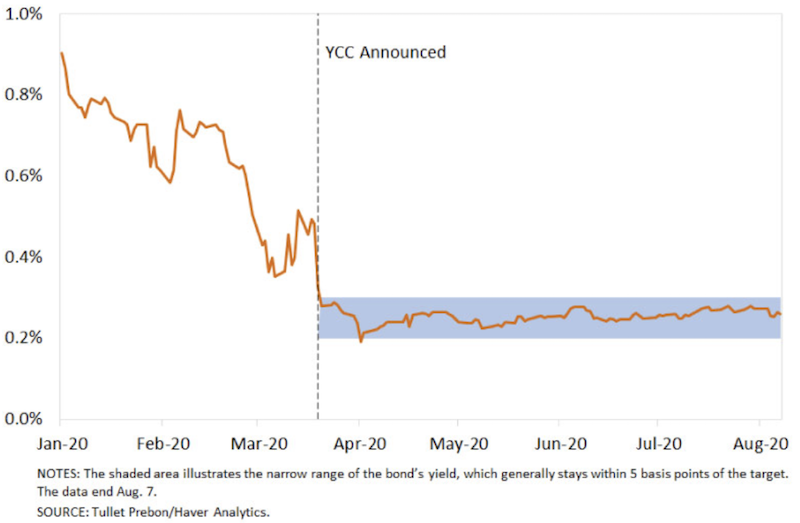

The Reserve Bank of Australia instituted its own form of YCC in March 2020. In its case, it targeted 3-year yields and put them at close to zero.

Yields on 3-year Australian bonds

The Federal Reserve is considering a similar YCC program, which would also tentatively target 3-year yields.

Looking ahead, how long central banks maintain these policies will depend on how successfully their economies return to full employment and inflation targets and how tolerant central banks will be if inflation rises materially above targets.

Inflation may not typically be a problem in economic recoveries in developed markets, but if inflation trends up to 3 percent while employment is not at an adequate level, then it puts central banks in a bind.

Characteristics of yield curve control policies

Targeted yields

The Fed during World War II and BOJ starting in 2016 set interest rates out more than a decade.

The RBA is doing yield curve control on a smaller scale, only targeting 3-year yields. The Fed is considering the same.

Of course, this can always be expanded into longer maturities if necessary.

Yield curve steepness

During World War II, the Fed targeted a relatively steep yield curve, with spreads between short-term and long-term interest rates at about two percent.

This helped bond investors enjoy steady returns and incentivized the private sector to help finance the government deficits.

On the other hand, a flat yield curve has been targeted in modern cases with the BOJ and RBA’s programs (and the Fed’s proposal).

Money printing

During WWII, the Fed expanded its balance sheet, providing liquidity to the private sector, who in turn used some of this to purchase government bonds.

Australia and Japan have not been as aggressive in printing money, though have been willing to in order to meet their goals.

Naturally, the lower the funding rate provided, the more will need to be printed in order to buy enough debt to support these low yields.

Fiscal stimulus

Yield curve control policies are most effective when the fiscal arm of the government takes advantage of these low rates to finance large budget deficits and put the money in the economy directly.

This could be financing tax cuts or instituting something like “helicopter money” where the money is put directly into the hands of households with incentives to spend it.

When adjustments of short-term interest rates and asset purchases cease to work effectively in stimulating an economy it’s inevitable that the monetary and fiscal arms of the government must coordinate. Some call this “MMT“.

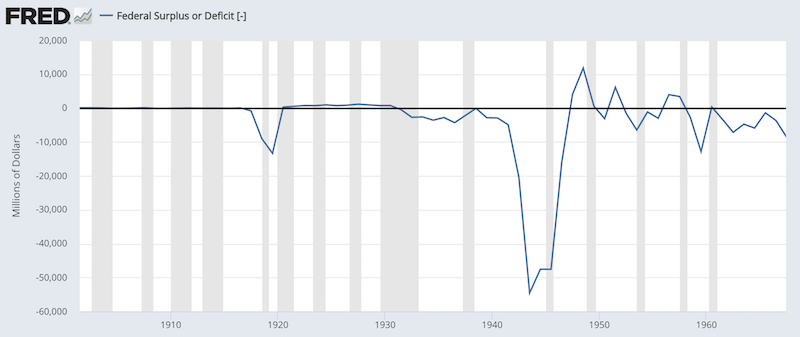

WWII saw huge fiscal deficits at around 25 percent of GDP.

Yield curve control configurations: US WWII vs. contemporary forms

In each case – the US in the 1940s and contemporary cases in Japan, Australia, and potentially the US – interest rates had been pushed down about as far as they can go.

Nominal rates can be pushed down to zero or a little bit below. Once they reach those constraints private sector credit creation is difficult to stimulate much more. Creditors’ lack of returns dis-incentivize further lending.

Short-term interest rates as well as long-term interest rates are lower today than they were in the 1940s war years.

The US policy situation back then featured a fairly steep yield curve (200bps spread between short and long yields) and significant liquidity production at the front end (i.e., the Fed buying short-term bonds) to finance a massive fiscal deficit of some 25 percent of GDP during peak war spending in 1943.

(Source: U.S. Office of Management and Budget)

Japan’s case, up until recently, was different from the Fed’s WWII situation given that money printing and the fiscal deficit was nowhere near as extreme.

Australia needs to finance a very large government deficit (around 15 percent of GDP) with little money printing and only a target on 3-year bond yields.

Yield curve control as a hard rate setting policy on long-term yields

Adopting yield targets specifically asserts that an economy requires accommodative financial conditions.

It is borne out of a combination of limited stimulative capacity with short-term interest rates at zero, asset purchases already flowing, and large fiscal deficits.

In any country – some sooner than others (particularly emerging markets) – this will lead to an undesired rise in interest rates as more debt is supplied to the market.

The Fed has studied other central banks’ uses of yield targets, most notably Japan (as it reached the zero lower bound decades ago). The desirability of the policy is mixed within the Fed, though it’s practically inevitable that they’ll implement the policy.

Like Australia, hard yield caps on shorter duration bonds will likely be done first (e.g., ~3-year issuances). This will provide some steepness to the yield curve. If necessary, they can switch into longer duration securities with time.

Federal Reserve guidance and market pricing already imply an extended period of very low/zero interest rates. With the level of indebtedness relative to income so high, the idea of raising interest rates is far off.

For example, if total debt to income in an economy is 4x across all levels, that means even a one percentage point rise in interest rates would raise debt servicing requirements in the US economy by around $800 billion or about 4 percent of GDP.

If $800 billion goes away from investment and purchases of goods and services and toward debt repayment, that’s a knock on economic activity. Moreover, when interest rates are low, it lengthens the duration of asset prices.

Lower interest rates discount earnings at higher multiples, helping to raise asset prices.

If the risk-free interest rate is zero and the risk premium on equities is three percent, that means earnings multiples are 33x (the inverse of that three percent – i.e., 1 divided by 0.03).

Raising rates by just one percent could knock a significant amount off asset prices. Hypothetically if a stock market index is producing ~100 in earnings, a 33x multiple produces an index value of 3,300.

If rates rise by one percent and the risk premium of three percent holds steady (1 + 3 = 4), then they’re discounted at that four percent, which is now a 25x multiple. At the same earnings, that’s 2,500, or about a 25 percent drop.

The Q4’18 tightening in US monetary policy was one such example where the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by more than was discounted in the curve, producing about a 20 percent drop in asset prices.

Either the central bank will keep interest rates low or they will run into inflation constraints that prevent them from holding yields as low as they effectively need to.

A front-end yield target would formalize the Fed’s commitment to providing easy financial conditions. This would contain any rise in interest rates driven by rising new Treasury issuance.

This would help improve growth conditions (productivity plus growth in the labor force growth) or raise inflation in the real economy (demand for goods in excess of their supply beyond a certain acceptable rate of change).

Given the central banks’ inability to meet their inflation targets in the past years, most will rather err on keeping monetary policy too easy. It’s better than the alternative of tightening prematurely and toppling over economies and financial markets that will tolerate little tightening without a commensurate rebound in activity.

Such a stance means that yields will likely rise much less and considerably slower than would normally be seen amidst a rebounding economy. One way to interpret this is that bond volatility and directional bond trades aren’t likely to produce much.

In the next section, we consider what a yield curve control paradigm can mean for bond traders — especially in relation to what investors have lived through in recent decades where supply and demand have still been the predominant forces in the bond market.

Yield curve control policies can work to anchor interest rates through swings in nominal growth

Traders and investors are not accustomed to the idea of pegged yields outside short-term interest rates, or what they earn on cash.

Pegged interest rates, when and where they occur, make bond trading radically different.

Under such policies, central banks are not as sensitive to moderate swings in the cycle and don’t change policy around movements in growth and inflation. Bond yields stay steady.

For traders and investors who use nominal bonds for diversification this has important implications. This source is basically lost if bonds do not help offset drops in equities, as had been the case for US markets from 1981 through 2020.

Depending on the steepness of the yield curve, nominal bonds could still remain attractive at longer durations, assuming they provide some yield.

Yield caps essentially take away the prospect of drops in their prices. Essentially longer terms bonds can become like a form of cash where a certain yield is received without much, if any, price risk.

This of course assumes that the yield cap commitment is credible and isn’t pulled to allow for higher rates. If and when such policies do end, there should be ample forward guidance from the central bank.

Yield curve control drawbacks

Every policy has drawbacks.

If the Fed is monetizing the government’s deficits directly, then it may cause inflation expectations to rise and undermine the long-run goal of price stability.

This occurred the last time the Fed engaged in YCC in the 1940s and into the 1950s. The US government relented on YCC in June 1947 when inflation was 17 percent.

This eventually led to the 1951 Treasury-Fed accord, which separated government debt management from monetary policy.

YCC could also distort market signals. Government officials receive information from the bond and equity markets regarding economic conditions to help inform their decisions. Controlling a part of the curve would do away with a portion of those signals.

An additional challenge is determining when to exit from such policies. Matters like zero interest rates, QE, YCC, and so on, are supposed to be temporary departures from normal policy frameworks.

When the economy normalizes, it would be important to communicate the exit strategy from a YCC policy in a clear manner to avoid any destabilizing outcomes.

Like any policy, credibility is key.

A steep yield curve can make longer duration bonds attractive

The returns of bonds and the attraction of holding them under a yield curve control framework depends on the details of the policy.

The relative steepness of the yield curve is a big determinant.

In the 1940s example, low bond yields at the front end of the curve and slightly higher bond yields in a standard upward sloping yield curve was a positive for bond investors.

Despite the huge issuance of bonds, the carry associated with borrowing at near-zero cash rates and buying longer term yields one to two percent higher locked in guaranteed returns.

However, returns eventually eroded in real terms. Central bank easing to support the massive fiscal deficits eventually drove up inflation rates both during the war and after.

Longer term bonds were still nonetheless better to hold than cash, as getting that 1-2.5 percent is better than getting close to nothing.

Today, yield curves are much closer to zero throughout the developed world. They are also flatter.

Accordingly, there is less opportunity to lock in carry.

The nature of the inflationary pressures is different as well.

Monetary policy has had no issue inducing inflation in the financial economy (i.e., the supply and demand for money and credit) through low interest rates and buying financial assets directly.

It has not been as successful in getting that financial asset inflation to move into the real economy (i.e., the demand for goods and services).

The measures by central banks to counteract the credit contractions in 2008 and 2020 largely filled the gaps to avoid deflation and were not inflationary in themselves.

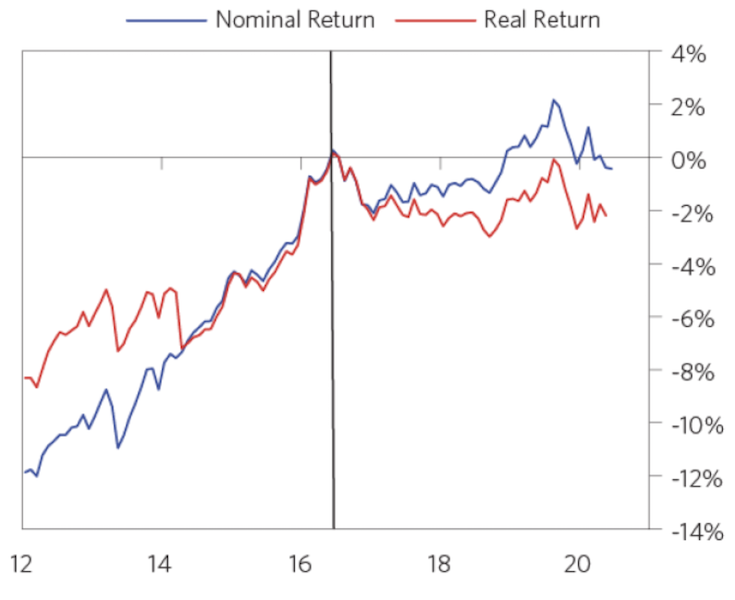

With Japan’s experience with yield curve control since 2016, the yield curve has been much flatter.

Cash rates have been -10bps with 10-year yields held around zero.

There also isn’t much available in the way for price appreciation (because yields are already at zero and can’t be lowered much more) and there is very limited carry opportunity (because short-term rates are about equal to longer-term rates).

As a result, returns for market participants have been week. Since the adoption of YCC in Japan, owning 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) have provided no returns in nominal terms.

At the same time, there has been little issuance from the fiscal side and inflation has been hovering at or a little above zero. As a result, returns in real terms have been only slightly negative.

Japan nominal rate bond returns (indexed to 2016)

Purchases of government bonds by the Bank of Japan

Yield curve control’s implications for non-bond asset classes

Stocks

Lower rates are supportive of stocks, holding all else equal.

A commitment to keeping borrowing costs low helps companies make value-additive investments.

If lower rates also make cash and bonds unattractive, then equities look better in relative terms.

Currency

The commitment to buy bonds whenever they hit a certain yield (or at the high point of a range depending on the details of the policy) is bearish for the currency.

That doesn’t mean it’ll necessarily decline relative to whatever it’s being borrowed against, but yield curve control is a policy that involves creating money to buy bonds.

Reserve currencies will be able to do this without seeing depreciation compared to those without reserve currencies.

The negative potential effects on the currency preclude some countries from easing monetary policy in such an aggressive way. This is especially true for countries that have limited borrowing and use of their currency internationally.

Gold

Gold is priced as a certain amount of currency per ounce. When currency is created in excess of the global gold stock, that tends to be a favorable tailwind for gold over the long term.

The dynamic isn’t that gold is going up (i.e., becoming more useful), it’s that the value of money is going down.

Gold generally benefits from a weaker US dollar. The USD is considered the world’s top reserve currency and gold is most responsive to real USD rates relative to any other currency.

But it broadly applies to all currencies. The greater the depreciatory pressure on a currency, the more gold will rise in relative terms.

In general, gold is an alternative when other currencies don’t work as well.

Holding all else equal, the easing of monetary policy is bullish for gold denominated in that currency. The lowering of real interest rates decreases the return of interest-bearing currency and bonds, leading to the desire to find alternatives.

That can also include commodities beyond gold and other precious metals.

Conclusion

Yield curve control (YCC) operates similarly to a policy rate. It’s a way for the central bank to control interests rates along some portion of the yield curve.

YCC is different from what most market participants are used to.

Instead of a yield curve where the front end is set by the central bank and the remainder by supply and demand from various participants in the bond market, the central bank caps interest rates on one or more maturities further out.

A cap on yields means a floor on prices for targeted maturities.

If bond prices of targeted maturities remain above the floor, the central bank does nothing. The converse is also true. If bond yields are below the floor, the central bank doesn’t intervene.

If yields rise above the yield cap (or range, depending on the exact policy), the central bank will purchase the targeted maturity bonds. This raises their prices and decreases their yields.

The most prominent examples of YCC throughout history include Federal Reserve policy during and after World War II (1942 to 1947), the Bank of Japan’s YCC policy adoption in 2016, and the Reserve Bank of Australia’s policy implemented in March 2020.