Volatility Risk Premium (VRP): Portfolio Strategies

The volatility risk premium (VRP) pertains to the compensation traders earn from insuring against market losses.

This typically involves selling options and/or other derivatives to other traders and investors to protect against the downside exposure they have in their portfolios.

To incentivize traders to underwrite these products, options tend to trade at a premium over the long-run. Namely, implied volatility is greater than realized volatility.

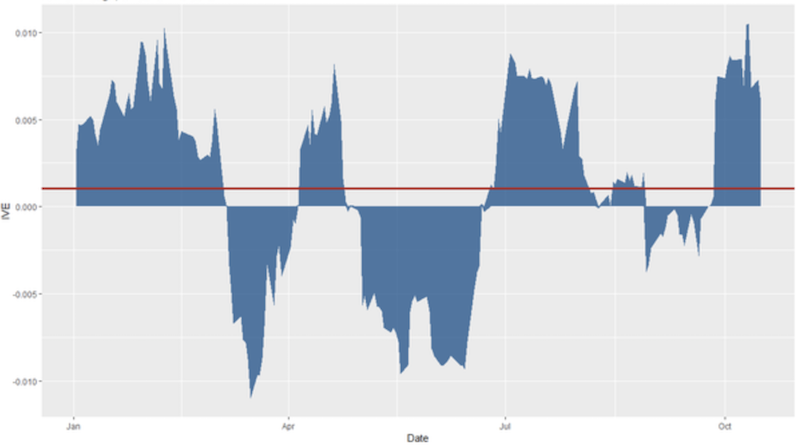

We can see this, for example, in how Apple’s options traded over most of 2018.

While there is certainly risk involved, as realized volatility often exceeds implied volatility (the blue patches below zero on the graph), there is a slight premium for options sellers to compensate them for the large potential downside they bear.

The volatility risk premium (also known as the insurance risk premium) reflects market participants’ risk aversion and propensity to overestimate the probability of significant losses.

This means a trader may be able to exploit these behavioral biases and risk averse preferences by underwriting financial insurance (via selling options) for profit.

Of course, this should be done in a prudent manner through proper risk management controls (e.g., delta and/or gamma hedging, or covering the position completely by owning or short selling the underlying security depending on the nature of the option).

In this article, we will look at the nature of the volatility risk premium through a basic strategy involving selling options on the S&P 500. It will show how an option selling strategy may generate positive returns over the long-run with medium risk.

And importantly, we will show how the volatility risk premium has a relatively low correlation to other traditional forms of investment returns. This can bring an additional diversification benefit.

The Basics of the Volatility Risk Premium (VRP)

The volatility risk premium (VRP) is a form of compensation for taking on an asset’s downside risk.

It exists in all asset classes and across different countries for the same basic reality that market participants want protection against risk-off events.

The value placed on such financial insurance, and why there exists a volatility risk premium, is likely because investors overestimate the likelihood that extreme market events will happen.

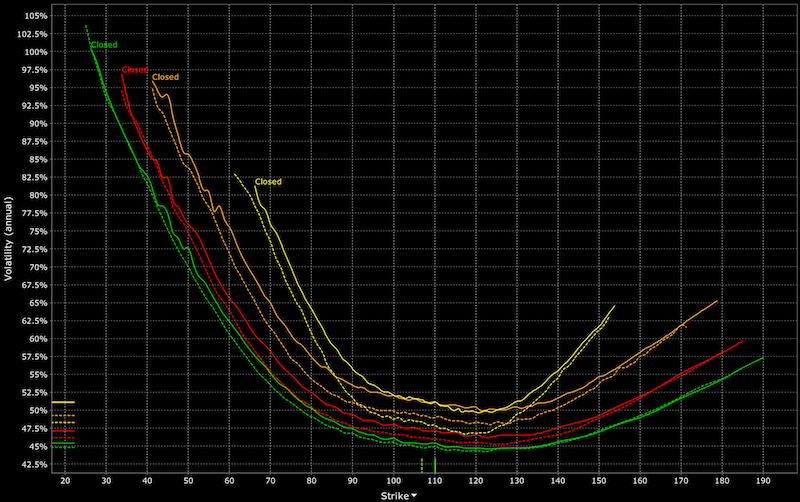

Risk aversion is a real thing. For example, in equities we can see it through the “volatility smirk”, which is a form of volatility skew.

Namely, the value placed on put options (i.e., to protect against downside) is higher than that placed on call options that are equidistant from the current price. Investors are biased long the equity market, and therefore have more demand for put options than call options.

This is a chart of Apple (AAPL) stock and we can see the bias toward put options (through higher implied volatility) across a wide variety of maturities.

(Source: Interactive Brokers internal interface (Implied Volatility Viewer))

Does risk aversion systematically boost the cost of financial market insurance?

This risk aversion may enable traders to collect the volatility risk premium from the markets over time in a systematic way.

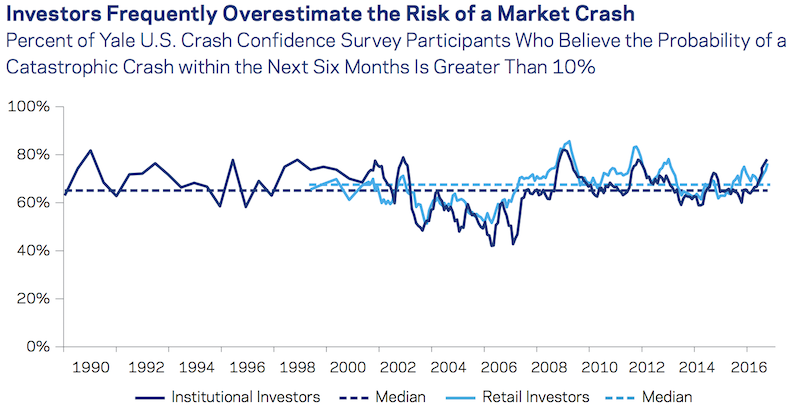

This type of behavioral bias to overestimate downside risk was found in a Yale University survey conducted by Goetzmann et al (2016).

Both retail and institutional investors were asked to estimate the likelihood of a “catastrophic stock market crash” within the next six months.

Since wording matters, here is the exact question:

“What do you think is the probability of a catastrophic stock market crash in the U.S., like that of October 28, 1929 or October 19, 1987 in the next six months, including the case that a crash occurs in the other countries and spreads to the U.S.?”

The number of those who believed the odds were greater than 10 percent consistently ran above 60 percent over nearly three decades.

(Data from April 1989 to December 2016)

In reality, the odds of a catastrophic crash over the next six months have historically been only around one percent, far lower than the ten percent a majority estimate.

The result of this overestimation may lead investors/traders to pay more – and insurers to demand more – in order to protect a portfolio.

Many market participants want to protect their portfolios by buying options to hedge their risk exposures. Such demand for this hedging leads to financial insurance being systematically overpriced over long periods.

This, in turn, is likely responsible for the existence of the volatility risk premium.

How to obtain the volatility risk premium (VRP)

Options are the standard way that financial market participants can sell financial insurance from one party to another. Therefore, it’s the standard way that traders can gain access to the volatility risk premium.

The buyer of the option typically wants to hedge against losses. The seller of the option, on the other hand, wants to profit from the selling or underwriting of the option.

This is very similar to the insurance business model. A company has a source of funds, which they use to underwrite insurance of various sorts. They must price risk correctly and spread their bets widely in order to have relatively stable profit.

The option buyer pays a premium, an upfront cost, that is collected by the option seller.

The option seller must hold collateral against the option in accordance to the estimated potential liability, both for the safety of the option seller and the broker facilitating the transaction.

Example

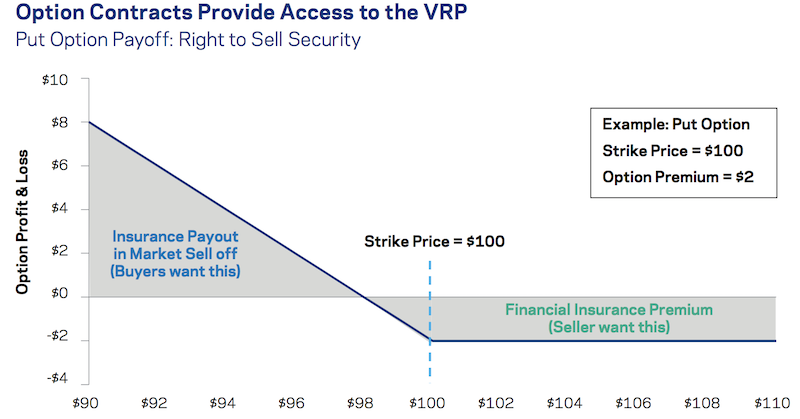

The graph in this section of the article shows an example of a trader who wants to hedge against a decline in a certain stock trading at $100.

The investor buys a put option with a strike price of $100 and a premium of $2 per share. When the option expires, it’ll be worthless if the stock is above $100. In such a case, the seller will have earned the full $2 per share premium and the buyer will have lost that $2 per share.

If the stock drops below $100, the buyer would exercise the option and the seller would have to fill the payment equal to the difference between the strike price and current stock price.

For example, if the stock falls to $99.50, the seller would have to fund $0.50 per share. Their profit on the trade would be their $2 premium minus the $0.50 payment requirement.

(Source: AQR. For illustrative purposes only.)

Options are accordingly like most insurance contracts where the buyer pays the seller a premium for bearing the downside risk.

And the insurance risk premium may be persistent over time for a couple main reasons:

i) The option seller needs to be incentivized to enter into the agreement, given the seller is most exposed to the risk of sharp price movements.

ii) As the Goetzmann et al study showed above, financial market participants tend to overestimate the likelihood that the market will “crash” or have some extreme downside event. This means portfolio protection might tend to be systematically overpriced, if only slightly.

If this was structurally true in a big way, the supply of options sellers would increase and bid down premiums, eroding their so-called advantage.

Anything that’s highly profitable attracts competition and reduces margins. In the insurance industry, a 2-10 percent net profit margin is typical.

The difference between an option’s price at the time it was purchased and its fair value is commonly known as the volatility risk premium. Though more technically, the volatility risk premium is the difference between the implied volatility of an option relative to the underlying security’s realized volatility.

This is the seller’s expected profit over time.

Evidence of the volatility risk premium

We can look toward history for evidence of the volatility risk premium over time. We can look from both the perspectives of the buyers and the sellers of options.

In just this case, we’ll use equity put options.

A buyer of equity put options is concerned about drawdowns from holding risk assets. Thus, this trader wants to protect against these losses.

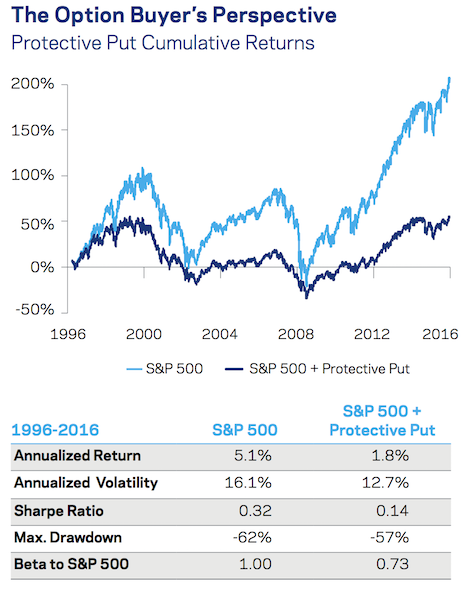

To test how well being long the volatility risk premium would have been, we can construct a portfolio that is long the S&P 500 while rolling one-month, 5 percent out-of-the-money (OTM) put options to hedge against these losses.

The graph below in this section shows the results of the “S&P 500 plus 5 pct OTM puts” strategy from the perspective of the option buyer relative to just holding the S&P 500 index on its own.

The hedged strategy does a better job of reducing the volatility of the portfolio, seeing a 12.7 percent annualized reading versus 16.1 percent.

The maximum drawdown, going from peak to trough, goes from 62 percent to 57 percent.

While the risk metrics improved, the average portfolio returns got worse, going from 5.1 percent to 1.8 percent.

The diminished returns were not worth the cost of lowering the volatility and overall risk. The Sharpe ratio of the portfolio declined to 0.14 from 0.32.

The general finding is that buying put options to hedge against risk-off events can be expensive whose benefits may not be worth their reward over the longer term.

(Sources: AQR, Bloomberg, OptionMetrics. Data run from January 4, 1996, through December 31, 2016. For the backtest of the protective put, the options used were front month S&P 500 put options, selected to be five percent out of the money, sized to unit leverage, and held until expiry. Returns are taken as net of estimated transaction costs and excess of cash (US 3-month LIBOR rates). No representation is being made that any type of trading or investment activity emulated under these conditions will achieve performance similar to those shown.)

Israelov (2017) takes a more in-depth analysis of the protective put option strategy (five percent OTM on the S&P 500) and finds that the risk protection benefits provided are not compelling due to “path dependency”.

This means that options have a strong element of timing behind them. Over longer term time horizons the theta decay erodes their benefits. We also discussed this as one of the drawbacks of buying options to protect a portfolio in this article.

From the put seller’s perspective

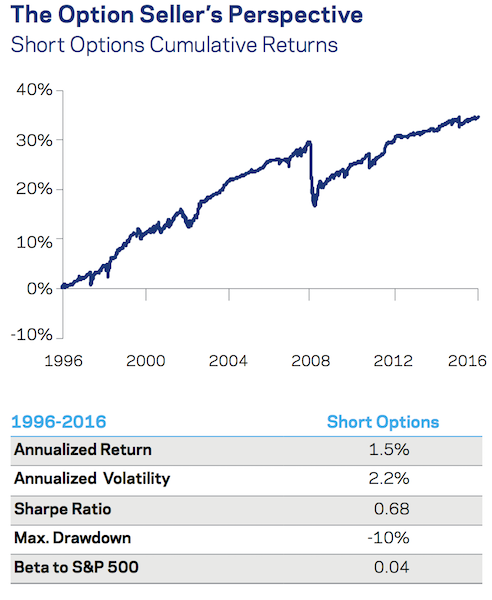

The put seller is selling five percent OTM options on the S&P 500 each month.

This illustrative example sells a five percent OTM monthly put options. This effectively matches the other side of the option buyer’s position.

(A portfolio looking to obtain the volatility risk premium would generally be constructed differently across a number of different dimensions in order to build a more optimal portfolio that improves return and lowers its overall risk.)

A trader who is doing this without covering the option (a bad idea) should expect to collect the premium most months (holding the option to expiration) punctuated by losses on particularly bad months for stocks.

However, in this example, the put seller hedges the equity exposure embedded in the options by shorting an equivalent amount of stock. This is known as delta hedging and is a common practice among options market makers, in particular.

This strategy going from the 1996 to 2016 period, as seen by the graph, has been profitable, producing annualized returns of 1.5 percent with a volatility of 2.2 percent.

The Sharpe ratio comes to 0.68, which is higher than the 0.32 Sharpe ratio produced from a passive S&P 500 strategy.

Drawdowns of the options selling strategy should also coincide with crashes in the stock market (e.g., 2008). Like with most forms of insurance, options pay out when adverse events occur, which is bad for the underwriter.

Overall, the strategy has generated positive returns and a quality Sharpe ratio over the long-term, with a low beta to equities (0.04).

Considering returns and risks associated with harvesting the volatility risk premium

Using a volatility risk premium strategy is helpful for a potential source of profitable returns over the long run.

It can also be useful given its ability to diversify to other sources of return given its generally low correlation to traditional asset classes.

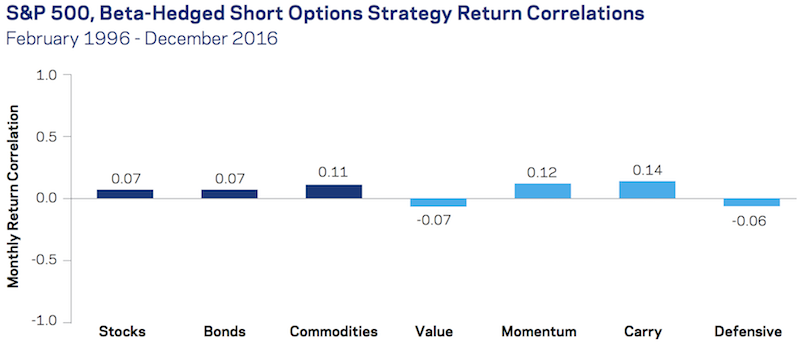

The image below shows the correlation of a beta-hedged equity option selling strategy relative to traditional return sources. It also includes selling options across multiple strikes.

There is relatively low correlations to standard asset classes (i.e., stocks, bonds, commodities, as well as the popular factor premia (i.e., value, momentum, carry, and defensive).

This low correlation may indicate that volatility risk premium may be a quality diversifying source of return for many traders.

Risks

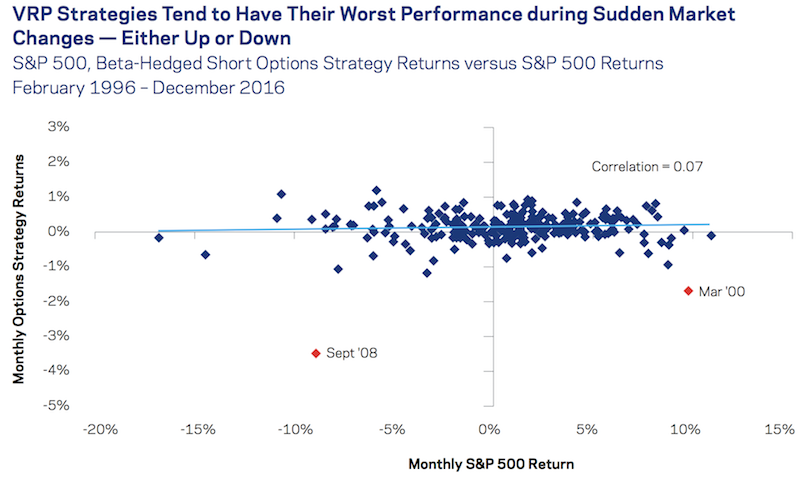

Average correlations to other asset classes can nonetheless be misleading.

This is because the predominant risk associated with a beta-hedged, option selling strategy is the exposure to sudden, large movements in the underlying securities.

The options premium can effectively absorb a certain amount of movement. Anything beyond that results in losses when these trades go against you.

A beta-hedged options selling strategy normally has little exposure to small moves in the underlying instruments. Options are, however, nonlinear instruments.

They have convexity embedded in them, given a premium is paid for control of a certain amount of the underlying, which can produce outsized profit/loss outcomes if a “cheap” OTM option leads to an eventual ITM outcome.

These sudden, sharp movements are, of course, the events that options buyers want immunity from and the option seller has underwritten insurance against.

The exposure is also why options sellers expect to be compensated for taking on this risk over the long run.

It’s also important to know not just average correlations but how it performs in particular market environments.

Certain strategies and/or assets that normally remain relatively uncorrelated can become very correlated in tail risk events.

While the full-period correlation might be low, the volatility risk premium strategy is susceptible to losing more during extreme market moves, both positive and negative.

(Source: AQR, Bloomberg, OptionMetrics. Beta-hedged short options strategy works by selling an equal amount of the following front-month S&P 500 options: 25-delta put, 25-delta call, and 50-delta straddle. These options are held to expiration and beta-hedged on a daily basis. Results are gross of transaction costs and fees.)

A general and key point is that the magnitude of returns matters, in either direction. Sharp movements with high daily realized volatility can lead to losses for a short options strategy.

Orderly drops or gains in markets, with low realized volatility, may still see positive returns or only smaller losses. So, a decline in the stock market does not necessarily mean losses for an option selling strategy.

Does selling options make sense when volatility is low and option prices are relatively cheap?

In a market like 2017, where volatility is abnormally low, options cheapen as these lower levels of volatility become extrapolated.

Israelov and Nielsen (2015) found, however, that the volatility risk premium still persists across all volatility regimes.

In a revised version of their 2015 paper, from January 2017, they wrote:

“Recent equity volatility is near all-time lows. Option prices are also low. Many analysts suggest this represents a good opportunity to purchase put options for portfolio insurance.

It is well-known that portfolio insurance is expensive on average, but what about in calm markets? History suggests it still is. We investigate the relationship between option richness and volatility across ten global equity indices. Option prices may be low, but their expected values tend to be even lower.”

In a low volatility environment, implied volatility has still tended to remain higher than realized volatility. In other words, selling options has still been profitable over this time, on average.

Overall, the reason why the volatility risk premium exists in the first place – i.e., to provide insurance against large moves that could create losses – should be true irrespective of the current volatility regime.

Integrating the volatility risk premium strategy into a portfolio

Traders looking to add the volatility risk premium into their portfolios have several options. It can be used as a:

i) Portfolio by itself

ii) Covered call strategy (i.e., buy-write, put-write, covered put)

iii) Volatility enhanced

iv) Part of a multi-strategy approach (e.g., 10 percent of one’s allocation)

Standalone volatility risk premium strategy

The standalone volatility risk premium strategy has a desired beta of zero to equities and other asset classes. The standalone has been the primary focus of this article.

As shown in preceding sections, the standalone VRP strategy can be a quality diversifier to equities, fixed income, commodities, and any alternative income streams. It generally produces relatively steady, positive returns in most market environments.

It generally has a strong Sharpe ratio over time. However, it can and will experience tangible drawdowns during sharp market swings. Allocations to it should be made with this type of tail risk in mind.

The options selling aspect will cover losses up to a point. But beyond that, the losses could stack up during those rare times when losses (or gains in a market that go against the position) are sharp and sudden.

VRP as part of a covered call strategy

The covered call strategy goes by different names, such as buy-write, put-write, or covered put (the opposite of the covered call).

The basic idea behind a covered call strategy is to get equity-like returns but with lower risk and beta to the markets.

Generally, the thinking behind a covered call strategy is that if equities decline, the options premium for the calls will help offset some of the losses.

Moreover, if stocks rise, you might lose some money on the options. But you’re still making a profit on net from the stocks going up and your short call option position is covered.

Accordingly, covered calls are used as a way to improve risk-adjusted returns. And they do on net over the long term.

Traders who don’t feel comfortable allocating a lot to the equity risk premium might allocate more to the volatility risk premium through a covered call strategy. (Israelov, Klein, and Tummala (2017) have a quality paper on covered call strategies.)

Given a covered call strategy generally has a lower beta to equities (sometimes as low as 0.5), the strategy generally has lower volatility than pure equity investments and a higher Sharpe ratio.

Volatility Enhanced

The volatility enhanced strategy typically has a beta approximately equal to the stock market.

Essentially, a beta-neutral volatility risk premium strategy is overlaid on top of a beta-1 stock portfolio.

This can be a long-only equity strategy or a long/short equity approach, such as 130/30 or some allocation that nets out to being long equities with a standard market beta.

The premiums earned from the volatility risk premium strategy are used to help enhance the return on the standard equity portfolio.

The general idea is to outperform an equity benchmark over the long run at comparable risk.

It is not a common strategy, though some versions of a VRP strategy might be used by managers whose value-add performance is pegged to a standard benchmark, such as the S&P 500.

Part of a multi-strategy approach

Many investors will not feel comfortable allocating to only a volatility risk premium strategy.

Instead, they might allocate to other strategies, including those that may do a better job of eliminating left-tail risk and drawdowns.

VRP may be just one of several strategies they might allocate to. It could be just 5 to 10 percent of a portfolio as the preferred way to access the diversification potential without going overboard.

Those who are new to a strategy should start very small, or even in demo settings, to get a feel for managing and trading it.

Variations on each of the above

The covered call and volatility enhanced strategies can be applied toward broad indexes to adopt a market following type of strategy with a twist (i.e., the volatility risk premium overlay).

They can also involve individual security selection to add alpha instead of the weighting by market cap approach, as is standard with indexes like the S&P 500. Certain approaches can help build a better stock portfolio by adding balance.

Managers seeking to add VRP strategies should consider their preferences with respect to overall objectives, risk tolerances, and asset allocation.

Final Thoughts

The volatility risk premium is a form of compensation that traders receive when they insure other entities against market losses.

The volatility risk premium can be thought of as a type of insurance. With options, like all insurance, the underwriter is looking for a premium in order to provide the service in the first place.

Existence of the volatility risk premium is largely a function of traders’ risk aversion and their tendency to overestimate the odds of downturns and extreme tail events.

A volatility risk premium strategy will work by trying to systematically exploit these behavioral biases and risk preferences by selling options (i.e., effectively underwriting market insurance) for a profit.

These strategies often take the form of covered call and/or covered put strategies.

Within the context of portfolio allocation, they are often overlaid on standard long/short equity approaches.

It can be used as a standalone strategy – i.e., an entire portfolio itself – or as a percentage allocation. Traders can use it as part of a long-only equities approach or alongside other return sources.

For example, an institutional fund might dedicate a certain percentage of its investment resources to different strategies:

- volatility risk premium

- risk parity

- managed futures and trend following

- venture and early-stage private investments

- emerging market funds

- high and low volatility variations of its strategies, and so on

Options contracts are the financial market’s way to provide insurance. Options are a liquid instrument and therefore provide the most straightforward way of providing the volatility risk premium, and can work as a type of liquid alternative.

Backtesting a basic delta hedged option selling strategy on the S&P 500 shows quality positive returns at reasonable risk.

It displays a high Sharpe ratio (approximately 0.7) with low correlations to traditional assets classes and returns sources, such as stocks, bonds, and commodities and standard well-known factor premiums.

Evidence suggests that the strategy can be a quality source of diversification when added to a portfolio in some allocation, making its case for inclusion in an investor’s portfolio.

But like any strategy, it has execution risk. It needs to be managed well to see proper results and it is not (and never) a sure thing.

Different investment managers will have different implementations and their own unique spin on it.

For example, we’ve covered the idea of building a VRP portfolio within the framework of a balanced portfolio approach.

Higher volatility is generally the enemy of volatility selling strategies.

Markets move and they don’t always move in an orderly way. Volatility will often run higher than expectations. This is the main risk associated with VRP strategies.

Like with any strategy, it takes time to be able to assess it. Because a few trades went sour or it produces losses after a few days is not sufficient time to accurately assess any particular implementation of it.

As shown in the Apple (AAPL) chart toward the beginning of this article, realized volatility can trend above implied volatility (i.e., losses for options sellers) for extended periods of time.

Like with all strategies, there will come periods where you might lose money or not make money even if your judgment is fine. As in any business, it’s a long-term game. It’s important not to be flighty and not to discontinue something at the first sign that things aren’t going exactly as planned.

Done well, allocating to the VRP may help improve trading and investment outcomes.

When assessing the merits of adding VRP or VRP overlay to their portfolios – however it may be implemented – traders will need to consider their strategy within the context of their overall objectives, risk tolerance, and general allocation preferences.