Building a Balanced Portfolio with VRP Overlay

In previous articles, we’ve covered the concepts of balanced beta and how to build a balanced portfolio in more depth. We’ve also covered the concept of the volatility risk premium, commonly abbreviated VRP. In this article, we’re going to combine the two concepts, building a balanced portfolio with what we call VRP overlay.

A balanced portfolio with VRP overlay is essentially where you build a balanced portfolio using balanced beta approaches but by capturing the volatility risk premium instead.

Namely, rather than capturing the normal risk premium from each asset class – i.e., the returns of stocks, bonds, commodities, and so on – you write options on the portfolio to capture the volatility risk premium instead.

Example

For instance, say you have a simple three-asset portfolio (that’s reasonably balanced) in the following allocations:

– 30 percent stocks

– 60 percent bonds

– 10 percent gold

To use specific instruments, let’s say it’s built by buying the following ETFs that would roughly provide the type of percentage allocation specified:

– 100 shares of SPY

– 500 shares of TLT

– 100 shares of GLD

A normal balanced beta approach would let the allocation run on its own. No derivatives are typically used and with only occasional balancing to keep the percentages in line.

A pure VRP strategy would write at-the-money (ATM) call options on each at a certain maturity, covering the entire position.

A covered call option caps the upside on the instrument in exchange for the option’s premium.

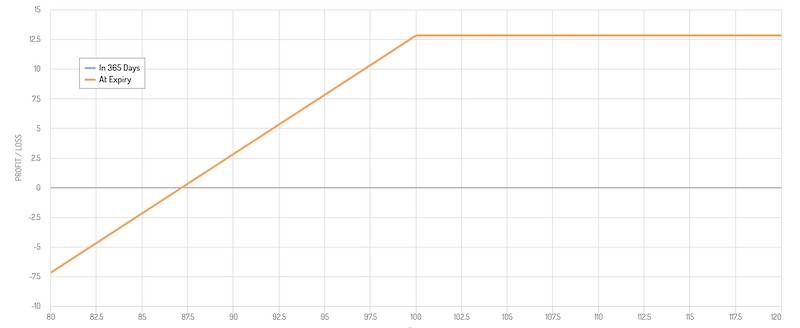

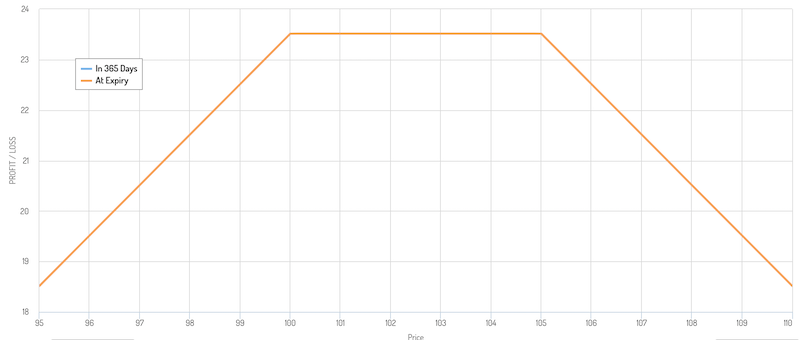

That gives an options payoff diagram similar to what you see below:

Since there are 100 shares for each equity options contract, 100 shares of a long SPY position would be covered with one call option contract. Five hundred shares of TLT would be covered through five call option contracts. One hundred shares of GLD would be covered with one call option contract.

Writing ATM calls would perfectly capture the volatility risk premium.

Writing OTM calls would capture a blend of the standard asset risk premium (i.e., from the appreciation in their prices) in addition to the volatility risk premium.

Writing ITM calls would essentially overweight the volatility risk premium.

The idea behind a balanced portfolio with VRP overlay

The existence of the volatility risk premium lies in the fact the option seller must be compensated for underwriting options (financial insurance).

Similar to most insurance contracts, the buyer is expected to pay the seller a premium as compensation for bearing the downside risk.

To incentivize traders to underwrite options, they tend to trade at a premium over the long term. In other words, implied volatility is greater than realized volatility over a long enough timeframe.

This needs to be true because the seller is exposed to the risk of sharp price movements.

The volatility risk premium – sometimes referred to as the insurance risk premium – reflects market participants’ risk aversion. They are willing to pay to avoid large losses and tend to overpay for the right to protect against significant losses (similar to other forms of private insurance).

Namely, market participants tend to consistently overestimate the likelihood of market crashes in the equities market in particular (hence the volatility skew when mapping the implied volatility across strike prices). This likely increases the value of downside protection.

Hence the volatility risk premium reflects the difference between an option’s purchase price and its fair value. This represents the seller’s expected profit over time.

Such overestimation of left-tail (or right-tail) risk may lead to market participants paying too high a price for portfolio protection over the long-term.

Some traders seek to protect their portfolios by buying options. Such persistent demand for hedging leads to financial insurance being systematically profitable, giving rise to the existence of the volatility risk premium.

Those on the sell-side of the trade are short a convex instrument. They receive a premium in exchange for what’s, in many cases, an uncapped risk instrument.

This is why those who sell volatility will typically delta and/or gamma hedge the short option exposure or cover the position completely by either buying or short selling the underlying security, depending on the nature of it.

Balanced beta lowers risk

The balanced beta aspect is used to lower the risk in a portfolio.

All assets have an environmental bias to higher or lower growth or higher or lower inflation.

When assets in a portfolio can be blended well, these biases can be reliably neutralized, leaving just the risk premium as the driver of the portfolio’s return.

The implication of this approach is that you obtain more return per each unit of risk.

One knows that for each individual option, the option seller has a slight premium to extract on an expected value basis.

If you’re lowering the downside volatility of the entire portfolio, then you should enhance the margin to be had by capturing the volatility risk premium.

We’ve mentioned in other articles on the balanced beta approach that if you balance exposures to broad asset classes well, you should improve the return to risk ratio by a factor of 2x to 3x.

Now let’s assume that the volatility risk premium balances out to about a 10 percent margin in isolation.

Namely, if you sell a covered call option for $100 in premium, your expected value on the option is $10 with a 10 percent margin.

However, if mixing assets well increases your return to risk by 2x-3x, your margin on the volatility risk premium goes up proportionally to the percentage your downside volatility was reduced by.

Another way to put it:

Selling volatility is profitable when implied volatility is higher than realized volatility.

When you’re diversified well, you’re still receiving “implied volatility” options pricing, but you’re reducing the realized volatility of overall your portfolio. That results in direct margin expansion of the strategy.

Doing this well can yield a big improvement and can substantially improve your results from a VRP strategy.

It can also act as its own unique stream of return, as a type of liquid alternative.

Balanced beta and balanced beta with VRP overlay can act as two separate portfolio constructions. Generally when you’re doing two different things, you should probably separate them if you can.

If you’re running a beta portfolio where you’re balanced and running an alpha portfolio where you’re betting on what’s going to be good and/or bad, it’s not effective trying to combine the two. It’s better to do them separately.

With a standard balanced portfolio, it’s focused on the standard asset risk premium. The other, the balanced portfolio with VRP overlay, is focused on the volatility risk premium.

Of course, there are many ways to construct a portfolio. One could also have a purposeful blend of each by writing OTM call options.

Such an approach would provide some upside from asset appreciation while still capturing the volatility risk premium.

Basic economics of the balanced beta with VRP overlay strategy

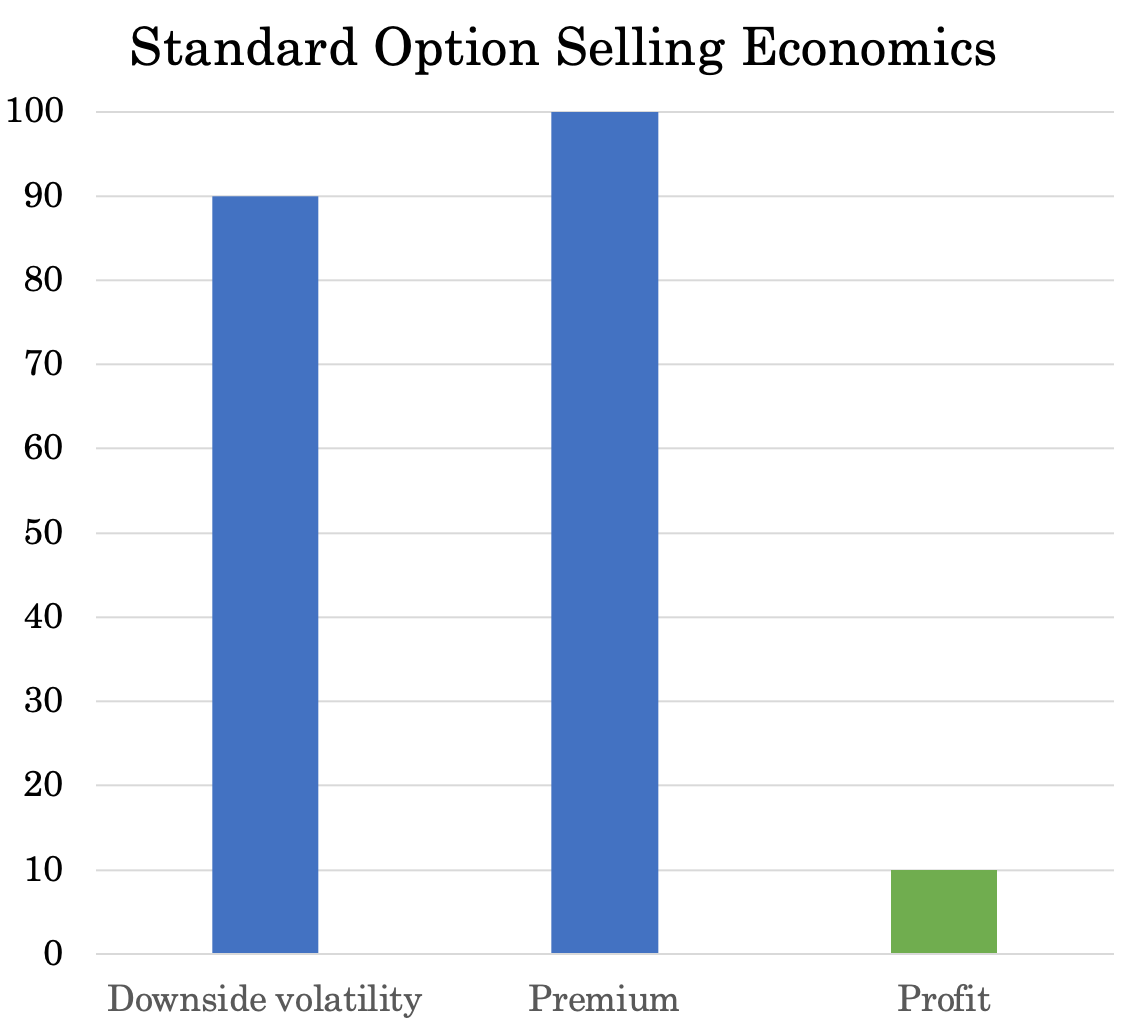

When you normally sell a covered call, you have a small margin from the volatility risk premium.

We called this 10 percent above. (Most private insurance businesses have margins of around 10 percent or a bit below.)

In other words, when selling financial insurance over the long-run, you have a certain amount of revenue – i.e., the options premium – and a certain amount of “expenses” that cut into that – i.e., we’ll call it “downside volatility”.

So, for every $100 in options premium you sell as part of a covered call, you have (say) $90 in downside volatility, leaving you with $10 in profit.

Under this stylized example you have something like this:

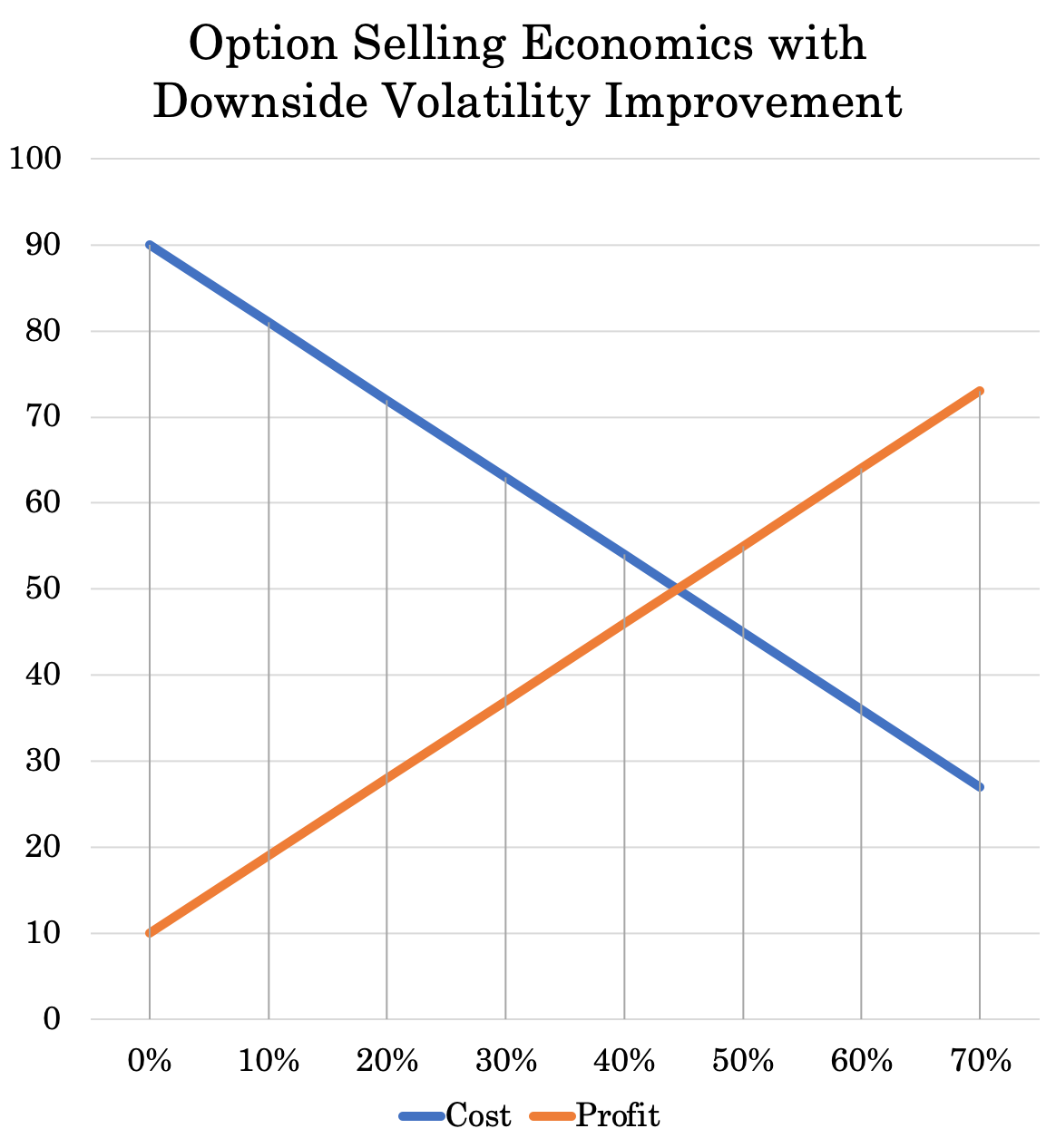

As mentioned earlier, when you diversify the portfolio well, you’re improving your return to risk by about 2x to 3x.

That means your options premium stays the same, but on average you will bear less downside volatility due to the effective diversification.

Instead of your downside volatility being 90, if it can be half (45), you’ll have increased your margins from 10 percent to 55 percent.

The graph below shows your baseline on the very left – i.e., downside volatility of 90 off a risk premium of 100, giving a profit of 10. Going rightward on the graph, it proceeds to show downside volatility and profit based on the percentage that the volatility downside was cut.

For example, if you reduce your downside volatility by 10 percent – from 90 to 81 – that increases your profit from 10 to 19.

If you decrease it by 60 percent – from 90 to 36 – then your profit goes from 10 to 64.

Additional asset inclusions

Adding VRP overlay to a balanced portfolio approach can also provide unique opportunities.

For example, natural gas is not normally included in most investment portfolios. It’s not a claim on cash flow like a stock or bond, or much of a type of wealth storage asset like gold.

It’s one of those assets that’s highly dependent on its own unique supply and demand characteristics.

So, it’s not something you would normally hold in any material quantity trying to seek out a risk premium. It’s typically traded by specialists. Oil and gas companies commonly use the natural gas futures market to hedge their exposures.

The benefit to all this is that it really doesn’t correlate much with other traditional assets. It’s also volatile, which means it’s a viable candidate for a VRP portfolio when not seeking traditional asset risk premium.

Example

The following is an example of a balanced portfolio with VRP overlay that’s more of a “set and forget” version given it uses year-long options maturities.

It’s a combination of ETFs, one futures contract for longer duration US Treasuries (ZB futures), and cash Treasury inflation protected securities (TIPS), though both could also be in the form of an ETF, such as TLT and TIP, respectively.

We have the following allocation:

21% Stocks (SPY)

35% Bonds (ZB Futures)

24% Inflation-linked bonds (TIPS)

13% Gold

3% Oil

4% Natural Gas

It’s done at a leverage ratio of about 3.4-to-1.

Options are written ATM for each asset twelve months out.

The total premium collected on the options is 25 percent of the total equity value of the portfolio.

Stocks currently pay around 7-8 percent annual premium. For long-duration Treasury bonds, it’s 5-7 percent. For gold, it’s 7-8 percent. For oil, it’s about 15 percent. For natural gas, it’s around 27 percent. (These vary over time.)

Leveraged at 3.4x, this comes to around 25 percent.

That means if all pieces of the portfolio finished ATM or ITM at expiration – and the portfolio was held constant – you’d earn about 25 percent.

If one or more the investments declined, that would eat into that return. If one or more of the assets declined by enough, then you could lose money for the year.

But since we have balance in the portfolio, taking the individual returns year by year and multiplying the exposure in this portfolio, the unleveraged balanced portfolio by itself had three mild down years throughout the sample period, highlighted in red font. (Our first full year of data for the ETFs used for each goes back to the beginning of 2008. IR is the US inflation rate.)

| Year | IR | Return | Bal | Stocks | Bonds | TIPS | Gold | Oil | NG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 0.09% | 1.46% | $10,146 | -36.81% | 33.93% | 0.04% | 4.92% | -56.31% | -36.08% |

| 2009 | 2.72% | 2.23% | $10,372 | 26.36% | -21.80% | 8.94% | 24.03% | 18.67% | -56.50% |

| 2010 | 1.50% | 10.36% | $11,447 | 15.06% | 9.05% | 6.14% | 29.27% | -0.71% | -40.58% |

| 2011 | 2.96% | 15.24% | $13,191 | 1.89% | 33.96% | 13.28% | 9.57% | -2.28% | -46.08% |

| 2012 | 1.74% | 5.37% | $13,899 | 15.99% | 2.63% | 6.39% | 6.60% | -12.44% | -26.86% |

| 2013 | 1.50% | -3.10% | $13,468 | 32.31% | -13.37% | -8.49% | -28.33% | 5.84% | 9.47% |

| 2014 | 0.76% | 10.41% | $14,870 | 13.46% | 27.30% | 3.59% | -2.19% | -42.36% | -28.61% |

| 2015 | 0.73% | -5.25% | $14,090 | 1.25% | -1.79% | -1.75% | -10.67% | -45.97% | -41.30% |

| 2016 | 2.07% | 5.59% | $14,878 | 12.00% | 1.18% | 4.68% | 8.03% | 6.55% | 7.73% |

| 2017 | 2.11% | 9.11% | $16,233 | 21.70% | 9.18% | 2.92% | 12.81% | 2.47% | -37.58% |

| 2018 | 1.91% | -2.72% | $15,792 | -4.56% | -1.61% | -1.42% | -1.94% | -19.57% | 5.96% |

| 2019 | 2.29% | 16.18% | $18,346 | 31.22% | 14.12% | 8.35% | 17.86% | 32.61% | -31.77% |

| 2020 | 1.29% | 8.08% | $19,829 | 2.94% | 17.66% | 8.33% | 23.30% | -75.36% | -24.44% |

You can see some deeply negative numbers in many years for oil and natural gas. Their volatilities are higher; accordingly, they are weighted lower and they provide a larger volatility risk premium.

The unleveraged balanced portfolio (blue) has less than half the volatility of a pure stocks portfolio (red). With its balance, it performs steadier over time, key to getting the most benefit out of the VRP overlay.

Other VRP overlay tactics

We asserted in a separate article that volatility risk premium strategies may yield a higher Sharpe ratio than traditional strategies that seek traditional risk premium.

As a result, some traders may actually choose to overweight the volatility risk premium overlay aspect of a balanced beta approach.

How might you accomplish this?

i) Sell ITM options

If you sell ITM options you limit the odds that you’ll lose the trade.

The downside is obviously no traditional risk premium to capture (it’s negative since you’re short ITM). In addition, the more ITM you go the more the option mimics the underlying instrument.

So you also reduce the volatility risk premium in conjunction.

But sometimes selling ITM options for purposes of most efficiently harvesting the volatility risk premium can make sense.

When to (possibly) sell ITM options

Such scenarios include markets with a certain level of volatility to them. In these cases, you might want to be ITM to give yourself leeway and neutralize your delta (your price sensitivity) to the security.

You may also want to sell ITM options when you have a certain correlation elsewhere in the portfolio where the underlying going ITM further continues to produce gains in your portfolio (and where going less ITM to OTM produces losses).

For example, many traders will notice that their portfolio does better in an environment where interest rates decline, which is traditionally favorable to financial assets.

Therefore, if they hold government bonds (which are essentially pure interest rate instruments), their portfolio might continue to make money even as the prices of these bonds go up and beyond the strike price of any call options they write against them.

In turn, they might choose to neutralize some of this correlation by selling ITM call options. That way, if interest rates rise (bond prices fall) they’ll absorb more of the loss by having more short exposure to the options premium.

With that said, if there’s a certain exposure in a portfolio that a trader doesn’t want, then there are multiple different ways of dealing with that.

It could be with options. It could also involve buying or shorting something to be better neutralized to it.

ii) Overweight the short options exposure

If you’re selling options as part of what’s effectively a covered call strategy, it doesn’t have to be a perfect covered call.

If you have 400 shares of a security, traditionally you’d sell four call options contracts to form a covered call.

To capture more of the volatility risk premium, you could, for example, sell five call options contracts.

This enables you to capture more of the insurance premium. But it comes with the downside of effectively making you short the security if you’re ITM at an effective rate of one-quarter of your former long exposure (or what your long exposure would be).

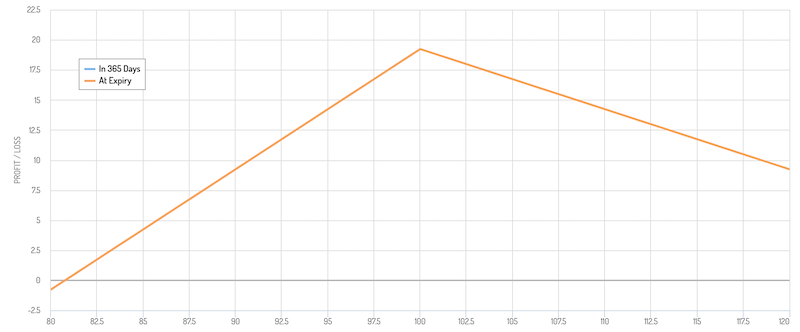

You would effectively have something between a covered call and short straddle trade structure.

The payoff diagram might look similar to this, looking more like a traditional straddle that’s overweight on one side:

If you don’t want to be short the security, at least right away, but still want to overweight one side of the trade, you can choose a call option further out-of-the-money (OTM).

For example, let’s say the security is trading at $100, so you short 100 calls as part of your normal covered call.

To get more of the volatility risk premium, you could also short the 105 strike calls.

The downside to this, of course, is that if price goes past $105, you’re now effectively short the security.

This would give more of a strangle looking payoff diagram.

This type of overweight strategy should be used carefully, particularly for stocks that are prone to large swings.

If the stock goes up enough, your new short exposure can more than wipe out the gains you received from the premium on your covered call, as the above diagram displays. Recognize that you are making trade-offs and should select carefully.

VRP Overlay Categories

Investors interested in adding a VRP component to their portfolios have several options.

The strategy can serve as:

i) a standalone portfolio

ii) part of an alternative portfolio (e.g., liquid alternative)

iii) part of a traditional buy-write strategy

iv) part of an equity strategy that uses volatility-enhanced components

We’ll briefly go through each of these approaches.

Standalone VRP Strategy – Beta: Approximately 0.0

A standalone VRP strategy will generally serve as a liquid alternative.

A true liquid alternative is beta-neutral. This means it acts largely independently from the stock market, the traditional benchmark.

Portfolios that are short options (the primary focus of this article) may be an attractive standalone strategy within an overall portfolio.

As shown, the VRP strategy typically has steady, positive returns in most market environments.

For many market participants, it may be a good diversifier to traditional allocations toward stocks, bonds, and alternatives, such as other equity and equity-like investment (e.g., real estate, private equity, and private business holdings).

Even though the VRP strategy demonstrates a strong Sharpe ratio over the long term, it can experience meaningful drawdowns during turbulent market conditions.

Running a VRP portfolio can often feel like it’s being carefully held together by glue. The calmer it is in the markets, the higher your margins on the strategy (i.e., the premium received relative to adverse market movement).

Therefore, any allocations to a VRP strategy should be sized accordingly to reflect this tail risk.

Part of an Alternative Portfolio – Beta: Approximately 0.0

For some traders, a standalone portfolio dedicated to a VRP strategy may not desirable, even if prudently sized.

In cases where an investment manager isn’t comfortable with VRP on its own, a diversified multi-alternative portfolio that includes VRP as one of several investment strategies may be the preferred way to get access to it.

Buy-Write Strategy – Beta: Approximately 0.5

This type of strategy involving buying a stock and writing a call against it goes by various types of names:

– buy-write

– covered call

– put-write (in the case of the opposite of short-selling a stock and writing a put against the position)

Like any strategy, how it’s implemented varies in terms of writing options that are ATM, OTM, or even ITM and the maturity of the option.

But they all have similar economic exposures.

The idea is to lower the beta to a traditional equities portfolio while generating equity-like returns at lower risk.

The beta is generally a more moderate 0.5 since it replaces some or all of the equity risk premium by allocating to the volatility risk premium.

A VRP allocation has a low correlation to equities. Accordingly, the strategy normally has a lower volatility than a pure stocks portfolio.

The general return to risk improvement typically generates a higher Sharpe ratio over the long-run for implementations that are managed well.

Volatility-Enhanced Equity – Beta: Approximately 1.0

Volatility-enhanced equity is the least common of these four main VRP strategy categories

This approach takes a standard beta-1 equity portfolio and overlays a beta-neutral VRP strategy over it. This is done to help outperform an equity benchmark by having active risk through the VRP component.

A volatility-enhanced equity approach stays invested in equities and aims to have comparable risk to a standard equities allocation but higher return over the long term.

The latter two strategies – buy-write and volatility-enhanced return – may also involve individual security selection as a way to add alpha.

Instead of a market cap-based portfolio, some investors will feel that they can add more value to a traditional equities allocation by tilting the portfolio toward, for example, defensive equities and stocks that traditionally provide better return relative to their risk (e.g., utilities, consumer staples, those with more stable earnings).

Whatever the case, VRP strategies that are engineered well exhibit low correlation to traditional stock, bond, and alternative investments, making a case for its inclusion in investment portfolios.

When assessing the merits of adding VRP to their portfolios – whichever general category or categories fit best – traders will need to consider their allocations in light of their overall objectives, risk tolerance, and general preferences.

Downsides of the Balanced Portfolio with VRP Overlay

All types of portfolios come with pros and cons.

Among the risks with a balanced portfolio with VRP overlay:

Balance will be disrupted by the presence of options

When you have a covered call structure, you sacrifice upside beyond a point in exchange for the option premium.

A balanced portfolio approach improves return relative to risk by offsetting various assets’ environmental sensitivities.

That means when one asset goes up, another is often going down.

If one asset goes up, the covered call structure will mean that at a certain price level you no longer have further upside. If the other asset goes down, the extent of the move may be larger than the option premium received on the calls paired with each asset.

A fundamentally balanced portfolio can become fundamentally unbalanced fairly quickly.

With a normal balanced portfolio, this would be offset a lot of the time since assets act differently. A drop in one is often due to an environmental driver that causes another asset to do well.

In a balanced portfolio with VRP overlay, the extent of your losses might be in excess of the options premium.

This also leads us to our next risk.

Volatility is bad for a portfolio that’s short options

A covered call will help offset a drop in the underlying. However, it will not do so enough if there’s a big enough drop.

Say you have a portfolio where you’re long stocks and long bonds.

If stocks go up, you’re covered by the call. If bonds go down, you can sustain a drop or slide of so much before you have a net overall loss.

A balanced portfolio with VRP overlay is fundamentally a sound idea when the portfolio is engineered well. You’re improving return to risk.

With that said, it’s still heavily a function of how realized volatility comes out in relation to implied volatility.

It’s important to highlight that there’s always going to be a certain amount of movement that eats into the margins of your VRP strategy.

This is particularly true when you have “pure” VRP strategy in place. Namely, when writing ATM calls, you have no upside from the price movement because you’re trying to capture as much of the volatility risk premium as possible.

Sometimes the movement in the portfolio will eat into all of it and more. Markets will inevitably move adversely to some of your positions.

Dynamic position adjustment in a VRP strategy

Some adverse moves against you can be dynamically managed if you’re a more active trader.

For example, let’s say you execute a buy-write strategy on a certain asset (i.e., buying something and simultaneously selling a call option). If the asset falls in price, the delta of the position (sensitivity to movements in the underlying) increases.

In other words, as the asset falls further from the strike price, the gains provided from shorting the premium become less, resulting in more mark-to-market loss for each additional drop in price.

To counter this, you could adjust the position by covering the short call and shorting another call at a lower strike price with a higher premium.

This can help attenuate the losses that occur from a slide in an asset.

You can make value-added improvements to how effectively you can extract the volatility risk premium through a strategic asset allocation mix, but there will be down periods, like with all strategies.

Capped Upside

When you ask some traders why they like buying options for outright bets, they will probably mention the very high or unlimited upside and the low relative downside.

When you’re on the other side of that and selling financial insurance, you have the opposite to contend with. You have a limited amount of upside and uncapped downside (when not managed appropriately).

VRP strategies have the general character of being “slow and steady” while getting knocked around when volatility surges due to this capped nature of the strategy.

Conclusion

A balanced portfolio with VRP overlay aims to combine the two concepts of balanced beta and capturing the volatility risk premium.

Balanced beta creates a fundamentally balanced portfolio that looks to eliminate environmental bias.

The VRP component aims to harvest the volatility risk premium among the various asset classes.

The VRP overlay usually involves selling call options against long positions in broad asset exposures from futures, ETFs, or individual instruments that are mixed together well.

The volatility risk premium is apparent on its own through the structural overvaluation of options to compensate those who provide insurance against market losses. Nonetheless, balancing assets well can help enhance the margins associated with the strategy.

But it also comes with downsides, including that the capped nature of the strategy given the covered call trade structures.

In light of that, when a position or set of positions is capped in its price upside, a balanced portfolio can quickly become unbalanced. Volatility is also naturally the enemy of volatility selling strategies in general.

But running a balanced portfolio with VRP overlay is a type of strategic alternative in a low-return world, where all the traditional asset classes going from cash to bonds to stocks no longer yield what they once did.

This reality is increasingly changing how investors approach their portfolios.

Investment managers will continually need to think about how they can innovate to come up with new approaches to keep returns flowing in a consistent way.