The Future of Trading & Investing: A ‘Store of Wealth’ Perspective

In trading and investing, you’re putting up a lump sum in the expectation that it will produce a stream of income in the future whether through the price movement (especially from a “trading” perspective) or through the cash that it throws off (particularly with respect to “investing”). For it to be enduring over the long-run, it must be a quality store of wealth. Money has two main purposes:

i) a means of exchange, and

ii) a store of wealth

A store of wealth is therefore a subcomponent of what money and currency is. Everything can be considered a type of currency in some form. Some assets are better than others. Fundamentally, it is something that holds its value well over time.

Going forward, it is especially important to consider, as some will be much better from a store of wealth perspective than others.

While the 2010s were a great decade for most assets – cash, bonds, stocks, some metals and commodities, real estate, and a new digital currency asset class – the 2020s and beyond are likely to see a big divergence both among and within asset classes.

There are different ways of thinking what a store of wealth is and what type of assets best characterize it.

For example:

i) Cash or short-term bills

ii) Bonds

iii) Stocks

iv) Gold, other precious metals, or commodities

v) Real estate, land, art, or other physical objects

vi) Digital currencies

We’ll go through each individually.

Cash or short-term bills

The most common base asset in a portfolio is cash or short-term bills (i.e., a type of fixed income investment with a duration of less than one year).

Its value doesn’t move around much over time, so it holds its value well purely from the perspective that it lacks volatility.

However, from a growth perspective, it is generally the worst investment you can have over time.

The way the capitalist system works is when people who have good uses for cash take it and produce a return on it. For that reason, you can be pretty sure that financial assets will outperform cash over time. When this isn’t true, you have depression-like conditions.

Even though the volatility of cash is low, it has a negative return in a few ways:

i) It has a negative real (i.e., after inflation) return. It also has zero nominal return throughout the developed world due to central bank policies that pin cash rates down to zero, or even a negative nominal return in some cases, like in Japan, most of developed Europe, and Switzerland.

ii) It has a negative return relative to the return of other financial assets. The risk premium associated with other financial assets is higher. This means you expect cash to lose value relative to those assets over time.

iii) Cash has a negative return relative to goods and services. It is eaten away by inflation over time.

While losing 2-3 percent per year compared to your typical return on bonds or 3-6 percent per year compared to stocks doesn’t seem like much, it does add up to a lot over time.

Losing 2.5 percent per year over 30 years is to lose out on a 2.1x return. Losing out on a 4.5 percent return per year over 30 years is to lose out on a 3.7x return.

Cash is important to have in some quantity to provide liquidity and optionality in a portfolio. But too much and you’ll underperform.

Traditionally how much to cash to hold beyond the basic purposes came down to how much it yielded. It also depended on whether this is domestic currency or foreign currency.

Cash throughout the developed world is no longer interest-bearing currency.

If it’s your own domestic currency, you care about the inflation rate because you want to know what your returns are in real terms.

If it’s in a different currency to what you earn your income in and pay your liabilities with, then you care about currency movements (unless you hedge the currency).

If you’re interested in a foreign currency, you will care about if the interest you receive is more than the inflation rate plus offset any depreciation due to its underlying capital flow (i.e., the balance of payments). This is a common consideration in emerging markets where they commonly earn their incomes in domestic currency, yet often borrow in different national currencies that have higher demand globally and lower interest rates.

When the real rates of return on cash and cash-like assets become unacceptably low, that increases the demand for other types of currency hedges that we’ll get into later down the list.

Bonds

Bonds are simply fiat monetary flows issued over time. A bond is basically a promise to deliver currency over time.

They are like cash but more volatile, depending on their durations.

Foreign reserve managers usually store their country’s savings in the currency of other countries through their sovereign bonds.

Bonds face the same issue as cash.

If the bonds are denominated in your own currency, you care about your return after inflation. If you take a 10-year US Treasury as the common global benchmark, that only yields 50-100bps. If inflation is about two percent, that’s a negative real return of some minus-100 to minus-150bps.

And because of less effective monetary policy going forward, greater political polarity, the rise of China and heightened geopolitical effects, there’s going to be a wider than normal expectation in the outcome of inflation going forward. That layers on another risk.

So, bonds are no longer that attractive throughout the developed world. If you want to go into emerging market bonds or assets, then you need to contend with the currency mismatch. If you own foreign-currency denominated assets, in general, you own a pile of that currency and are also fundamentally making an FX trade.

Namely, if you’re long assets of another country in their currency, you’re effectively long the currency. Owning some foreign currency for diversification purposes can be desirable, but not to too large of an extent.

If the yield of bonds becomes low, like it is now, then like cash, it becomes closer to a funding vehicle than an investment vehicle that marks this new paradigm of trading the markets going forward.

This, too, drives the desire to look for alternative stores of wealth.

Stocks

Some companies can be stores of wealth due to the nature of their cash flows.

You have things like consumer staples and basic healthcare that will do well and gradually expand their earnings over time. We know those products always get bought no matter what.

People need to buy food and basic medicine to physically live. That means the stability in their earnings is higher and their stocks are likely to increase over time.

Economically sensitive companies are less effective as stores of wealth.

You could also include utilities in there as a type of stable cash flow sector, to an extent, as people always need to pay their bills with respect to water, electricity, gas, and so on.

Because of the longer duration of equities (their cash flows are theoretically perpetual), you’ll get structurally higher volatility.

But this is also true of other types of assets that serve as stores of wealth like gold (about 20 percent annualized volatility relative to about 15 percent for US stocks) and longer-duration bonds.

On the other hand, you have the companies in sectors like airlines, auto parts, movie theaters, restaurants, malls, and so on, that gets killed by a huge drop in income and especially with people staying in during 2020.

So, there are certain types of companies that are better stores of wealth than others. You can be assured that over your investing horizon – 10 years, 20 years, 50 years – that these stable, always-in-demand products and services are going to produce income for these general types of companies.

Other examples of companies that are basically the source or foundation of productivity – i.e., certain fintech and technology companies – have a much longer duration in their cash flows. Some don’t make much money now relative to what they’re priced to make going forward.

These types of companies have benefited a lot from the reflationary dynamics as central banks added a lot of liquidity to the system.

We covered in a separate article about how you can invest in a basket of stocks that’s likely to act as a store of wealth.

Stocks can also protect you to a certain extent during a period in the economy when inflation runs higher relative to expectations. We’re also in a period where we have large deflationary forces in the real economy accompanied by large inflationary forces in the financial economy where central banks are buying assets to inflate financial wealth so that it helps get into spending and income.

Financial assets can’t out-earn the earnings of the broader economy over time. With the gap in financial assets versus the economy, policymakers will prefer to inflate their way out of it and produce poor real returns rather than letting prices collapse and produce poor nominal returns.

Inflation stats will be hard to interpret and will be choppier. The deflationary forces are large and could overwhelm the money creation. The less elastic goods and services like food and healthcare are already seeing some inflation.

Gold, other precious metals, or commodities

We have covered the point of gold in a portfolio and investing in the precious metal in prior articles, so we won’t go too in-depth here.

However, we can summarize that gold has been a store of wealth for thousands of years and has outlasted the currencies of various empires and nation-state that have come and gone.

It is often the currency that these empires, nations, and people fall back on when fiat currencies cease to work well. It holds its value and is tried and true.

That still holds today, with central banks and the big institutional investors looking toward it as a currency hedge when real interest rates run below a level that makes their returns intolerably low.

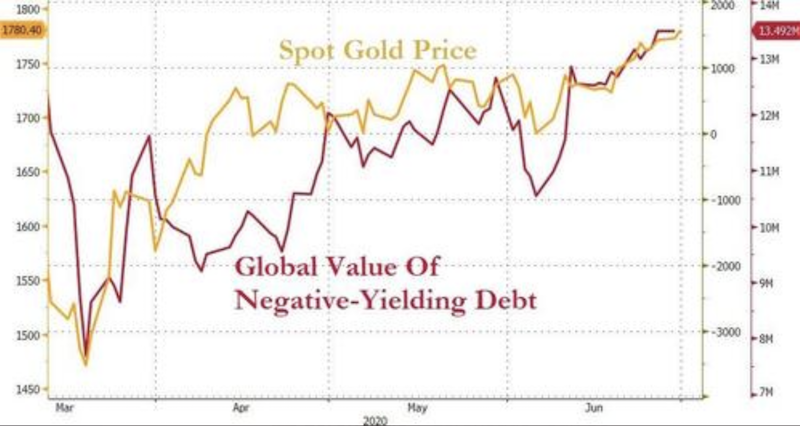

This is why there’s a correlation between the price of gold and the amount of negative-yielding debt globally.

Gold is the inverse of money over the long-term. In other words, gold is a contra-currency. It’s priced in whatever currency it’s being compared to – gold per dollar, gold per euro, gold per pound, or whatever it may be.

With all the obligations that need to be monetized (hundreds of trillions), you can see that gold is likely to be priced reasonably higher over the next 10, 20+ years, though their is plenty of volatility in its price.

In the US alone, there’s about $300 trillion in the present value of liabilities. That’s 15x GDP. You won’t get the productivity to produce the income, so all of those obligations will have to be monetized. There will be a ton of printing that needs to be done.

Gold is not reliable for short-term price forecasts, as it’s not the most liquid market and it competes for capital like every other asset class and that induces the volatility. But over the long-term, having a piece of your portfolio in gold and diversification to other currencies and monetary systems can be both return-enhancing and risk-reducing.

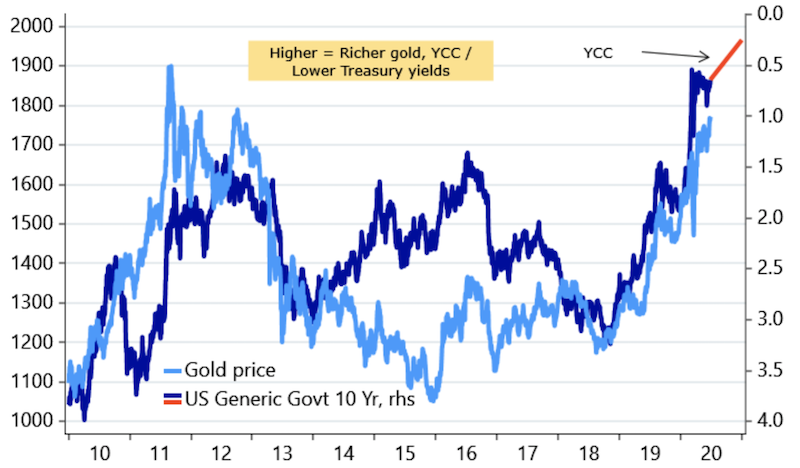

Precious metals would likely continue to perform into a light-YCC implementation

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Real estate, land, art, or other physical objects

Some might also cite real estate because the amount of land is fixed and whatnot.

But real estate is about context.

For example, simulating out the sales mix of how B2C companies transact business, 90 percent or more of all sales are likely to be e-commerce by 2040. Some things are more amenable to being sold online than others.

Malls will always have a place, but less of one. More of the space will need to be repurposed as its value declines for the traditional uses.

So, you can’t be too sure how exciting mall stocks are in terms of how they’re going to hold their wealth over the next 5+ years. (Of course, what’s collectively known on a dollar-weighted basis is already reflected in the price.) If managed well, they could be fine.

But with the consumer staples, you know that demand is stable and execution risk is minimal. People are always going to buy food, soap, basic medicine, and so forth. You can’t say that about purchasing goods through malls.

Some argue real estate and land stocks are almost like staples because of the perpetual demand. But it’s probably not the best argument because the use of the land and what it’s good for changes over time. Real estate is also a highly leveraged sector, so accordingly it’s highly interest rate-sensitive.

On the other hand, if you’re buying a warehouse that’s near a big population center, that could make sense as a real estate bet because of its value for e-commerce. It is complementary to the secular trend.

Real estate and land can be inflation hedges. They’ve been used that way historically. Many hard objects have been. (In Weimar Germany, the inflation and eventual hyperinflation became so bad tools and machinery (not to use) and even rocks became desired assets to hold.)

But context is important.

Digital currencies and cryptocurrencies

The vast majority of digital currencies and cryptocurrencies are not the best stores of wealth because they’re too volatile. The buyers and sellers in these markets are predominantly smaller speculators looking to make a profit off the movement rather than see it as something that holds its value over time.

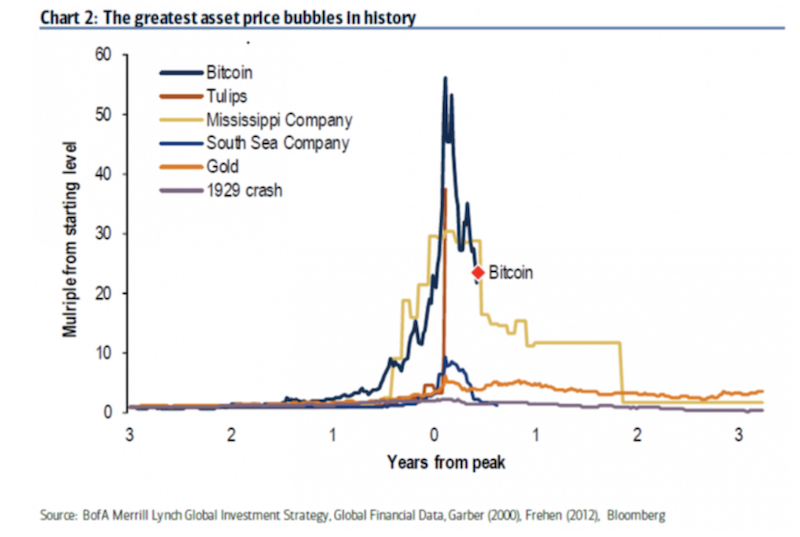

Bitcoin, in particular, became one of the more popular asset bubbles in recent memory after its public attention in 2017 fueled widespread speculation.

Each individual cryptocurrency has the following matters to contend with:

– The ease with which each the technology can be copied. The popularity has led to thousands of competing cryptocurrencies.

– As a market primarily of speculation, most of these cryptocurrencies are involved in a big “greater fool” game

– It doesn’t fit the traditional markers of a currency: a means of exchange (limited transactional use) and a store of wealth (due to the high volatility)

– Uncertain value as an investment

– Uncertain value as a currency hedge

As an investment, it can’t reliable defer investment into the future.

As a currency hedge – when monetizations make real rates unacceptably low – it doesn’t have the track record of alternatives to lend confidence to central banks and the big institutional investors that it’s viable in that respect. They’re going to go to other alternatives. Cryptocurrencies have a very long way to go as a source of reserves for the big buyers in the markets.

In the financial world, such as fintech firms and technology companies, some are launching digital currencies or are in the early stages.

The primary aim is to extract efficiency improvements in some form, such as a) technological implementations to improve existing payment infrastructures or, b) as transactional mediums to allow consumers, businesses, and other customers to purchase goods, services, and/or financial assets within a proprietary platform.

The in which cryptocurrencies can create value will be dependent on their ability to streamline operational processes, create value for customers and business partners, reduce costs, and do in a way better than alternatives (i.e., incumbents and new entrants).

Any digital currency system needs sound governance so that it’s fair and dependable to all parties involved. It needs a robust legal framework, and appropriate regulation to develop a system that’s sound and can scale up to broader adoption in both financial and non-financial contexts.

Governments will naturally have concerns about such systems, as they represent off-the-grid payments systems that aren’t under their purview and can lead to legal gray areas or as a conduit for illegal activity. This process will go on over time.

Stores of Wealth: The Broader Picture

There is no crystal ball in trading or investing. It’s a matter of probabilities, distributions, and expected values.

Betting too much on any given thing has been shown to be dangerously historically.

All of the above are options to consider, but putting too much of your money in cash, bonds, stocks, gold, commodities, real estate, forms of digital wealth, or anything can entail high risk as a store of wealth or as growth assets in their own way.

We’re at a point where:

i) Central banks (in the developed world) are out of stimulant in the normal ways it can boost financial markets and the economy when they are weak.

ii) There is an enormous amount of debt and debt-like liabilities (e.g., pensions, healthcare, insurance, and other unfunded liabilities) that will increasingly be coming due and won’t be able to be funded with assets and the income they produce.

In other words, we’re now in a world where:

a) Real interest rates are so low that investors holding this debt will not want to hold it and will look for other stores of wealth they think are better.

b) The need for money to fund debt and other liabilities will create a squeeze. Because the incomes that these assets generate won’t be nearly enough to service them, there will be an increasing amount of monetization. It’s not politically acceptable to not make due on retirement or healthcare obligations.

There will have to be some combination of large deficits that will be monetized, currency depreciations (the main channel), and tax increases (to a lesser extent, because there’s a limitation to how much taxes can be increased before losing revenue).

This set of acute trade-offs is likely to cause increased conflicts between the “capitalists” and the “socialists” or those on competing ends of the political and ideological spectrum.

Over this time, those who hold debt are very likely to receive very low to negative nominal returns and also negative real returns.

Moreover, the currency that these debts are held in are likely to weaken because of the increasing monetizations and lesser overall desire to hold it when the yields on the cash and debt are low.

Essentially, cash and debt will almost be like a wealth tax. Some of that debt will still have some level of credit risk and volatility to it based on its duration, which will be further downsides of holding it.

As of the end of June 2020, there are about $13.5 trillion worth of sovereign debt with negative interest rates attached to. When there is negative nominal return, and likely even more negative real return, investors start searching for alternatives. This is why the amount of negative yielding debt tends to positively correlate with the price of gold. It’s an alternative safe haven.

Negative interest debt is worthless for producing income. The exception is when they are funded by liabilities that have even more negative interest rates.

At best, these investments are passable stores of wealth to hold principal. But they are not likely to be safe because they offer poor real returns and it’s also possible that rates rise and their prices go down. However, on the latter point, central bankers are not likely to allow that because lower asset prices would harm the economy.

Price gains are not signs of better investments

Generally, investors like it when interest rates decline across the curve because it boosts the present values of discounted cash flows, leading to higher prices for the investors.

But they tend to pay more attention to the price gains from the declining interest rates and less about what the implications of those falling interest rates mean for future returns.

In other words, holding all else equal, when interest rates fall, they create higher prices. This creates the illusion that the investments are good. In reality, the returns are simply future returns being pulled forward due to the present value effect. Consequently, future returns will be lower.

This process can only go so far.

When interest rates reach their lower limit, that stimulation capacity is gone. The effective lower limit is around zero or slightly less than zero.

At a point, creditors are not going to lend if they’re receiving less than a zero percent return on their money.

For savers, at a point they’re not going to put much of their money with someone else when the principal loses value over time.

When interest rates reach these barebones levels, the prospective returns for risk assets are increasingly pushed down to the expected return on cash. On top of that, the demand for money to pay down debt and various debt-like liabilities is increasing.

When there is little to no room left for stimulation to produce more of this present value effect and risk premiums shrink between asset classes, there’s not much left. This is true practically all across the developed world.

As this is going on, more liabilities will be coming due and in higher amounts. As more is squeezed out of assets, it will become increasingly hard to create enough money to meet those obligations.

At time goes on, there will be more conflict due a bunch of unappetizing trade-offs associated with the reality that not everybody can be satisfied:

i) How much of all these IOUs will be kept and how many will be defaulted on.

ii) How much will need to be met through higher taxes on high income earners (which will cause a level of tax migration and can, if pushed too far, harm productivity and overall tax-take).

iii) How much will be satisfied through higher budget deficits that will need to be monetized – i.e., “printing” more of it, which will depreciate the value of money and the real returns of the investments, particularly those holding debt/credit assets.

We know from history that central banks will do whatever it takes to keep economic activity high by holding down both nominal and real interest rates through asset purchases.

They control how much money is created and can flood the financial system with liquidity. (Whoever the central bank buys from gets the cash, to then use on other things.) It is the creditor who will suffer from the low return.

The implications of a low-return world

When cash and bond investment yield very little, nothing, or a negative amount, there won’t be enough income to fund the liabilities. They might be okay for storing wealth, but have limited use beyond that.

To finance expenditures, holders of these assets will need to sell off principal. This diminishes the value of their remaining asset pool.

This means they will need either:

i) higher returns on the smaller base of principal (which is not realistic to get), or

ii) the principal will eventually run out, especially with a lower asset base progressively producing less income.

This will also occur at a time there will be greater internal and external conflicts.

Internally, the left and the right of societies facing these problems will fight over how to divide the wealth and what policies to pursue.

At the same time, there will be greater external conflicts as between countries related to trade, capital, and global influence.

In this type of world cash and bonds become less safe as a store of wealth.

Cash doesn’t yield much and will lose its value over time.

Bonds are a claim on the future promise to deliver money, which will be devalued, as it’s the most discreet and least controversial way of relieve debt burdens without cutting spending or raising taxes.

While cash and bonds are likely to provide poor real and nominal returns, it’s not likely to lead to a price reversal in the bond market from their very high prices (and lead to higher interest rates). Interest rates need to remain low to keep the debt servicing burdens in check. So, central banks will buy them when necessary to keep interest rates down and prop up their prices.

This is similar to the “yield cap” or “yield curve control” monetary policy framework from 1942 to 1947 that was characterized by large debt monetizations.

What assets perform well in a reflationary environment?

While central banks have a limit to how low they can reduce interest rates across the curve, the can provide as much liquidity as they want through various channels to accomplish their objectives.

Although returns are likely to be very low in real terms it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll be bad in nominal terms.

The big question is which investments perform best in a reflationary environment when large numbers of financial obligations are coming due while there is more internal and external conflict to deal with.

We noted above that some types of stocks can perform this function, such as those on the leading edge of developing the latest technologies. Some of these stocks might be wildly overvalued and crash and burn, while some will continue to innovate.

It will also mean what currency or currencies are the best to hold as a store of wealth when the reserve currencies are all undergoing devaluations as their central banks look to reduce debt burdens. They have unconstrained power to do so under fiat monetary systems.

Because most people extrapolate what they’ve gotten used to, they perceive that the best investments will continue to be stocks and equity-like investments, such as real estate (typically bought on a lot of leverage, exacerbating its risk), private equity (ditto on the leverage component), and venture capital.

This may also seem true when central banks are doing whatever they can to reflate.

As a consequence, the world becomes leveraged to be long risky investments. But because of the enormous amount of money that’s been printed, the returns of those assets are also being pushed lower to the returns of cash and bonds, already yielding nothing in a large fraction of the world.

Not only are the real returns much lower compared to what we’ve seen historically, but the risks are also higher than normal.

The investments that are likely to do best are those that do best when the value of money is being deprecated and internal and external conflicts are high, like some forms of precious metals.

Moreover, traders and investors, being used to liking assets that have done well in the recent past, will be inclined to believe those returns will continue to be good even as the conditions shift to make that unlikely.

As a result, they become underweight the assets that are better positioned to do well (i.e., gold).

If they had a better balanced portfolio to reduce risk, they would own more of this type of asset, which can both enhance returns and lower risks.

Final Thoughts

Cash, which is now money that doesn’t bear interest throughout the developed world, is important to have in some quantity.

But it’s a long-term underperformer relative to other asset types – especially assets that retain their value or increase their value during periods of reflation.

– Cash yields nothing.

– The 10-yr US Treasury gives 50-100bps. Traditionally the 10-year gives you 2 to 3 percent over cash. Now the bond yields are down to keep all rates low.

– Stocks usually give about 3 percent annually over the 10-year.

So just following those risk premiums, stocks over the next decade are likely to give 3-4 percent in nominal terms, not much in real terms. This mirrors in economic terms. Productivity is 1.5-2 percent, inflation might be 1-2 percent, labor force growth is not much at 0-1 percent. Add all that together, and that range gives you 2.5-5 percent nominal.

Certain companies are inherently better stores of wealth as they participate in the distribution of resources. Some companies qualify a lot more in this respect than others.

For example, airlines, auto parts, and restaurants are not perfect stores of wealth because most people don’t technically need those things. Goods like cars and houses are economically sensitive because they’re typically purchased with a lot of credit.

On the other hand, utilities, consumer staples (food, personal care, basic medicine), and certain types of healthcare are practically always going to get bought. They’re physically necessary to live everywhere in the world.

Any financial asset, whatever its character, cannot over the long-run exceed the growth in the value of the goods and services on which it’s a claim. When US nominal GDP growth is going to average about 4 percent or a bit less over a long time horizon, those extrapolating the returns of the market over the recent past, expecting those to continue, will be sorely disappointed.