Negative Bond Yields – Who Buys Them?

Negative bond yields don’t make sense at first glance. Why would anyone pay somebody to hold their money for them? Normally when you put up a lump sum of cash to invest, you expect a return stream out of that in the future. It doesn’t seem prudent to see that pile of money decrease in value over time.

There are a few reasons:

1) Traders expect that the return, in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms, will be higher than it is in nominal terms.

In Japan, Switzerland, and some other parts of Europe, their economies have gone through spells of deflation. In other words, the value of simply stowing money under your mattress has gone up in value. If a bond yields minus-50 basis points and the inflation rate is negative-100 bps, then the real yield is effectively +0.50%.

If we look at the value of bonds in the US, which are currently about 2%, and take the inflation rate that is also approximately 2%, that means there is no real yield to these bonds. All of the effective return is eaten up by inflation (though still superior to having that cash receive no yield at all, as it might in a checking account). If we take into account the taxes on the coupon distribution or capital gains, then the return is even less and perhaps negative.

2) Traders use bonds as a means to speculate on the direction of interest rates.

If you expect interest rates to decline, then buying the longest-duration form of bonds would be one way to place a wager on that. The higher the duration of an asset – i.e., the amount of time it would theoretically take to get your initial investment back – the more sensitivity it will have to interest rates.

In other words, much of low-yielding debt is used for speculative purposes. They don’t provide much or anything as an investment, little as a diversifier, so they become used as a way to ideally sell to somebody else down the line if their thesis on interest rates – or belief of broader “risk off” sentiment – proves correct.

3) A hedge against equities

Stocks and bonds have had a negative correlation for most of the past three decades. This is not always true, but traders tend to extrapolate the past and believe that relationships that have held up recently will continue to hold true in the future. Even if bonds yield negatively, then can remain a cheaper hedge than buying puts on equities, bear spreads, or other hedging trade structures.

4) Demand from foreign investors.

It’s unfair to compare the yields of bonds denominated in different currencies. This is because their actual yield when they are hedged into the foreign trader’s currency can be quite a bit different than the nominal yield it returns to domestic traders.

The rest of this article will focus on the fourth reason.

If you are a trader based in the US, you will be most interested in the yield you can obtain on a foreign bond in US dollar terms. If you do not hedge a foreign currency denominated bond back into USD, you will have explicit currency risk. If a bond yields 2 percent but the currency moves against you 10 percent, your yield is now negative-8 percent. If you are leveraged 5x, then you’re down 40 percent.

Instead, you need look at the forward exchange rate priced into the curve and figure out the hedge adjusted yield of the trade.

We can look at the forward curve of future exchange rates as they are currently priced into the market. Some brokers have this inbuilt into their set of features, such as Interactive Brokers.

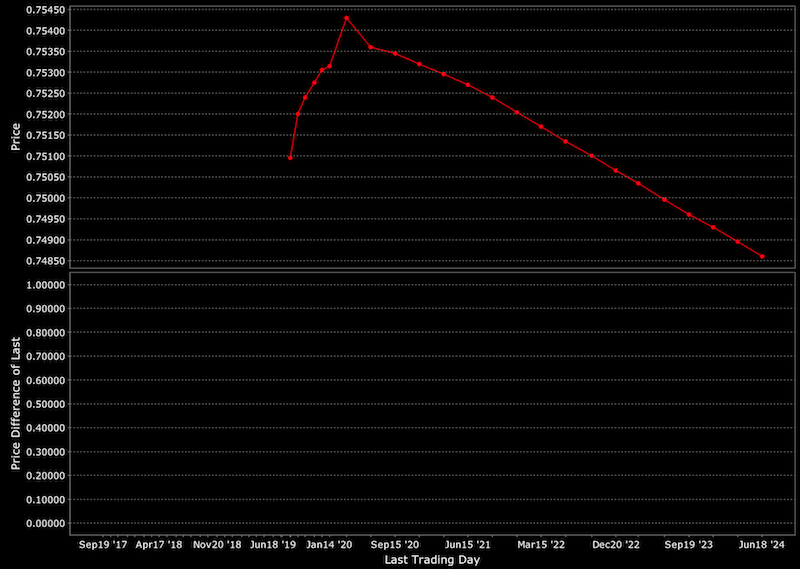

CAD/USD

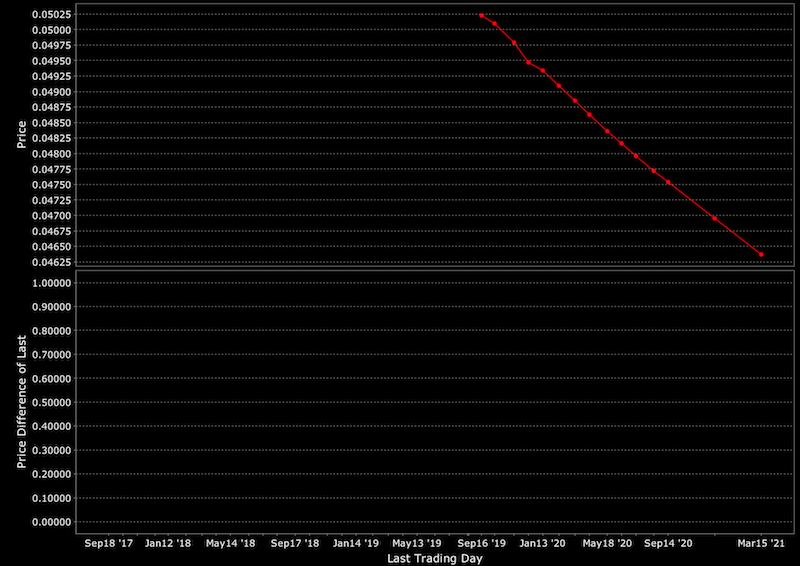

For example, here is the CAD relative to the USD:

For reasons related to interest rate parity, currencies with lower interest rates are expected to trade at a higher exchange rate in the future. The market may anticipate inflection points in this relationship in the future, such as when one central bank eases relative to another, causing the slope of the curve to change.

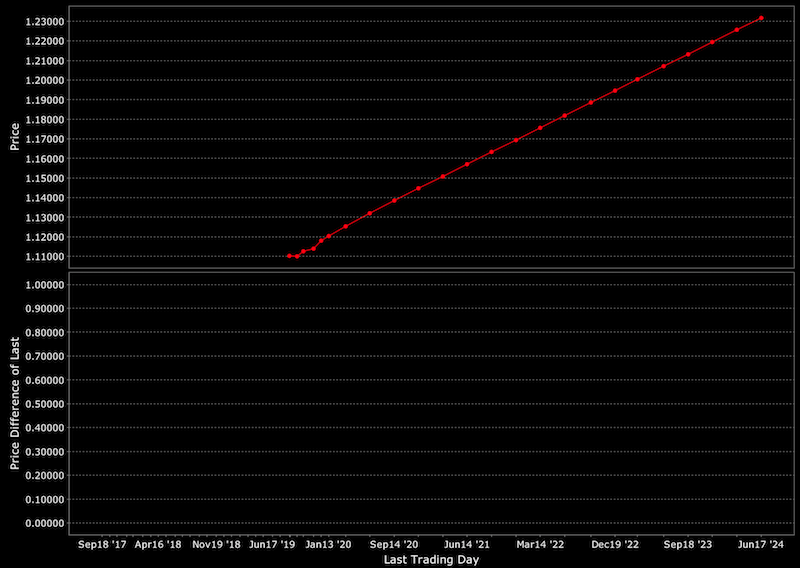

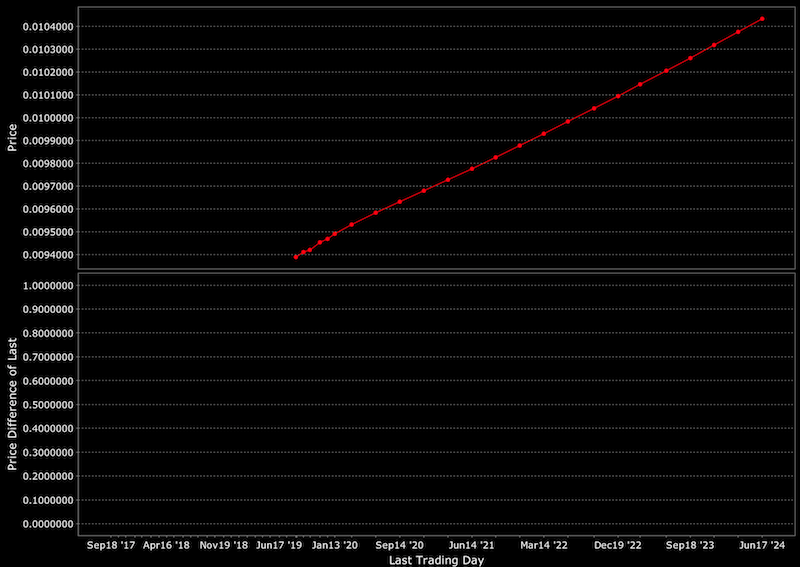

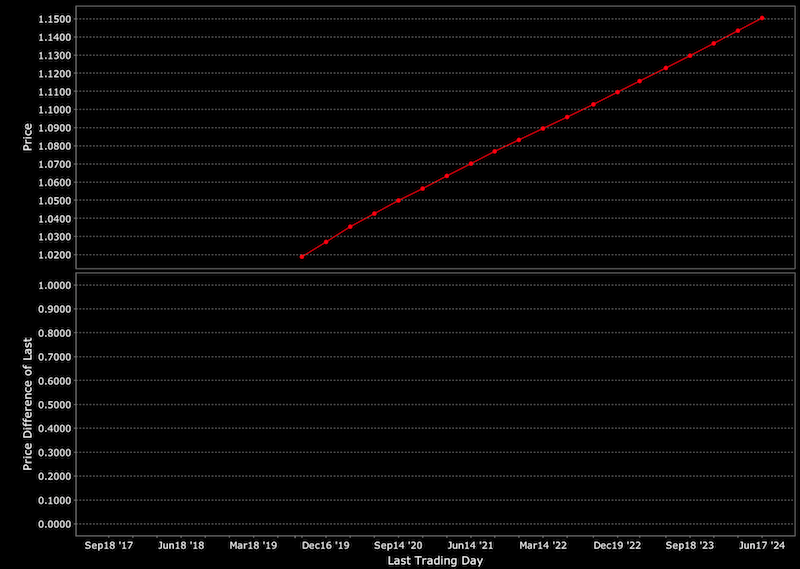

You’ll see that the EUR, JPY, and CHF are all in contango (upward-sloping futures curve) against the USD given they have lower interest rates than the US.

The interest rate parity formula is as follows:

F = S * (1 + domestic interest rate) / (1 + foreign interest rate)

F = forward exchange rate

S = spot exchange rate

Example

If we compare the US and Germany, where the forward 1-year interest rates are 1.79 percent and minus-0.82 percent, respectively, and plug this into the formula:

F = 1.108 (1 + 0.0179) / (1 + -0.0082) = 1.137

EUR/USD

(Euro expected to appreciate relative to USD)

JPY/USD

(Japanese yen expected to appreciate relative to USD)

CHF/USD

(Swiss franc expected to appreciate relative to USD)

Given the Mexican peso cash rate yields 7.75% against just over 2% for the USD, the peso is expected to depreciate against the dollar.

MXP/USD

(USD expected to appreciate relative to Mexican peso)

Using forward curves to determine currency hedged yields

The 1-year implied forward exchange rate on the EUR/USD is 1.138 at the time of writing, which we also approximately derived above. (It’s not precisely accurate as other yields outside Germany’s factor into the forward EUR exchange rate. Certain other assumptions also need to be true, such as the frictionless flow of capital.)

The forward exchange rate is tradable as either a forward or swap. The spot rate is 1.108.

The implication is that, that in one year’s time, selling a EUR/USD 1-year forward would net you about 2.75 percent in yield dividing those two figures. This is because you are effectively selling the EUR/USD exchange rate in one year’s time for a higher price than the prevailing spot price. That generates a yield.

If a US trader is buying a German bund at minus-75bps, the currency risk is hedged out by selling the EUR 1-yr forward (or swap). This converts the bund proceeds into dollars. Then we take the “yield” from the forward or swap, subtract the nominal yield of the bond (minus-0.75 percent) and come up with a dollar-hedge yield of 2 percent.

In reality, it is no different than investing in a US Treasury bond yielding 2 percent outside of the extra step of needing to hedge the currency.

This process also works in reverse. From the European or euro-based trader’s perspective, this currency hedge works in reverse. Unlike the US trader, who generates a positive yield on the hedge, the European trader pays it.

Accordingly, for the European trader, if he wants to buy a US Treasury bond at 2 percent and the cost of the hedge – to convert the proceeds of the Treasury bond back into euros, his domestic currency – he has to pay 2.75 percent. The effective Treasury yield for the European trader is thus minus-0.75 percent.

In other words, despite the US being the only major advanced economy that has rates a decent bit above zero, it also sports negative bond yields to many foreign investors because of the cost of the FX hedge.

That’s no different than what the German bund costs despite the fact that the nominal yield differential ostensibly tells you that US Treasury bonds are the better investment.

Moreover, for the US investor, having a currency that yields higher than other developed market currencies provides the ability to diversify among various different markets while receiving a yield comparable to US Treasuries.

In Switzerland, the 1-year forward rate on the USD/CHF is right around 1.05 against roughly 1.02 for the spot rate. Swiss cash yields about minus-1 percent in CHF terms. Converting back to dollars, gives a FX-hedged yield of about 2 percent. For those who want more duration, they can earn up to 2.5 to 2.6 percent on the long end of the curve.

For Italian sovereign debt, some of the only EUR-denominated debt that still largely has a positive nominal yield due to its greater economic and political risks (which creates credit risk), the dollar-hedge equivalent yield on cash is about 2.5 percent, with the longest duration bonds giving north of 5 percent.

Negative bond yields validated through the carry trade

This is another form of the carry trade. The foreign interest in these assets through this process – taking negative bond yields and converting them to positive yields via the exchange rate – helps explain why negative yields happen.

The relative lack of FX volatility also has helped, in turn, keep sovereign bond markets stable. When currency volatility picks up – which is what can and will happen when monetary policy reaches its constraints in terms of inability to lower rates further anywhere along the curve – unwinds in carry strategies can be quick and violent (e.g., 2008).

Currency volatility can also rise if there’s a flight out of risk assets – e.g., the Federal Reserve doesn’t ease interest rates fast enough relative to what’s discounted into the forward curve.

A move into US Treasuries and even more pronounced inversion of the yield curve would result in a narrowing of the rate differentials between the US dollar and other reserve currencies – e.g., EUR, JPY, CHF, GBP.

Given that the US has much more room above the zero lower-bound, it’s assumed that the Fed can reduce interest rates faster than these countries and close the rate differential. This would close the forward exchange rate. Accordingly, the currency hedges would no longer yield as much and US (and other foreign) demand for these negative-yielding bonds would no longer be as strong.

In turn, this could cause European yields to rise if there isn’t sufficient support from the central banks (as the primary source of alternative demand). This has knock-on effects in other asset classes, such as decreasing the prices of equities through the present value effect and increasing the value of the euro (or whatever currency the bonds are denominated in).

This also puts pressure on the most challenged economies in the euro area (e.g., Italy) who are locked into a quasi-pegged currency system and would be hit hardest by a stronger euro because of their liabilities. In effect, it would be an undesirable form of monetary tightening.

Conclusion

To fairly compare the yields of different bonds around the world, we need to calculate the currency conversion to put everything is constant terms. The yield of German bunds to US Treasuries is apples to oranges. Only when we compare the two in uniform dollar or uniform euro terms can we understand what the actual yields are. They are actually quite similar depending on which parts of the curve we are comparing. Likewise, traders who use other base currencies will need to do their own calculations.

The exposure of the carry strategy to volatility shocks and reliance on steady central bank policy and rolled derivative contract structures creates risk. All forms of carry trades are essentially synthetic short gamma trades. This means their success heavily relies on dampened volatility and overall “smooth sailing”. When forward interest rate differentials change or exogenous factors cause upward spikes to volatility, the benefits to carry trades can erode quickly.