Inflation Targeting: Why Do Central Banks Do It?

Inflation is one of the main overarching fundamental drivers of asset prices (the other being economic growth). Both central bankers and macro-oriented traders tend to have an obsession with inflation and its forecasting. Inflation and inflation expectations feed into interest rates, which are the bedrock of finance and how financial asset prices are valued through the present value effect.

Inflation targeting is the most foundational central banking practice. It is always set to a low, positive targeted figure or range. It is never set to a negative value as this means prices, production, income, wages, and spending will typically contract. This is because deflation is typically indicative of a credit contraction and debt service payments exceeding incomes on a pervasive level in the economy.

Even when deflation is benign in nature – namely, aggregate supply exceeds aggregate demand – this signals that output, wages, and spending largely aren’t being maximized.

Higher inflation also makes fixed-rate debt easier to service. In other words, it is easier to “burn off” debt when the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) rate on it is lower.

A zero percent inflation rate can’t be viably targeted because there are inexorable, structural deficiencies preventing a perpetually stable price level. Competition in the economy isn’t perfect enough. Namely, there exist monopolistic, monopsonistic, and oligopolistic elements that prevent a long-term flat-lining in the price level.

Unless money and credit are expanded at least as fast as the rate prices are increasing in an economy, incomes and spending will fall, output will be reduced, and unemployment will rise.

A 1% target isn’t commonly viewed as effective because the volatility in inflation is such that deflation is likely to manifest at various points under this policy aim. And, in general, it isn’t viewed as optimal relative to a slightly higher level.

Therefore, in most developed countries, a target or target range in the 1.5%-3% range is most common and appropriate. Going above this point for elongated periods is not recommended, as at some point price stability will need to take precedence over output. Keeping inflation within this approximate range will provide a monetary environment to help maximize employment, wages, spending, production, and output and lead to longer-lasting growth.

Inflation targeting is viewed as a no-brainer in central bank circles

Virtually all central banks have some version of inflation targeting.

– The US Federal Reserve targets price stability within the context of maximum employment.

– The European Central Bank targets inflation of just under 2%.

– The Swiss National Bank targets price stability.

– The Bank of Japan and Bank of England both target stability in prices and the financial system.

– Some central banks also include a mandate to keep the currency stable. The Bank of Canada, Reserve Bank of Australia, and Reserve Bank of New Zealand all follow stable currency mandates in part.

The currency directly impacts inflation through the influence on the relative affordability of goods and services in the international market. Currencies also price in movements in interest rates, which are under the purview of central banks. A big part of what influences the price or relative level of a currency is what it pays relative to another currency.

Many traders are currently attracted to the US dollar (as of July 2019), because its cash rate (currently over 2%) is high relative to currencies like the Japanese yen or Swiss franc, which carry negative cash rates.

Many economists will argue that targeting inflation will take care of the employment situation on its own.

In other words, stable low positive inflation is a common hallmark of a healthy or improving labor market. A focus on employment only, on the other hand, could lead to a lack of price stability in either consumer or producer inflation or financial instability (i.e., excess purchases of assets on leverage).

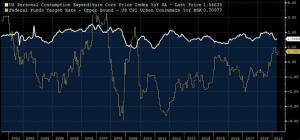

Low rates and asset buying have been shown to have a minimal effect on product and service inflation in highly indebted developed economies. Below is the US federal funds rate (overnight interest rate set by the Federal Reserve) versus the Fed’s preferred inflation measure.

Each of the past three economic downturns in the US were due to financial stability concerns. In 1990-91, the problem was a bubble in commercial real estate and high-yield bonds. In 2000-2002, there was a bubble in tech stocks. In 2007-2009, it was a bubble in residential real estate.

This is why we see many central banks adding a financial stability – “asset price inflation” – mandate, even if it’s simply in a de facto sense, like in the case with the Fed.