Trader Psychology: Why Some Strategies are Hard to Deal With

In a previous article, we covered liquid alternative trading/investing, a type of long/short, typically market neutral(-ish) strategy that provides liquid, uncorrelated returns to traditional asset classes. These types of strategies, because of the market neutral character of them, are a good stepping stone into covering a bit on trader psychology.

Even despite how much evidence and intuition can go into building a robust strategy, everything has downturns. This makes trader psychology particularly important. Being able to handle everything that can and will go wrong is essential to the effective execution of anything you do.

Trader psychology can make or break your trading

We know, for example, that betting on companies with high margins, strong cash flows, quality value metrics (e.g., low price to book and low price-earnings) will tend to beat companies that are the opposite (e.g., unprofitable and expensive).

There’s a lot of long-term evidence and economic intuition behind this.

But -2 standard deviation events will happen. Because of loss aversion, which has been well-studied in psychology and applied toward finance, losses are more painful than gains.

Everyone who has traded and invested knows this experience where gains “feel” otherwise normal (or good), while losses of the same magnitude feel worse or even terrible.

The obvious thing to do is to examine the process or strategy you’re undertaking during drawdowns, though that can be hard to do. Trading and investing is not an easy thing to do for those who are flighty or more emotional than logical, getting in when times are tough and moving in when things are good.

Assets tend to look like better investments when they go up and worse investments when they go down. Though the perception, clearly, should actually be the opposite.

Rising assets are generally more expensive assets and falling assets are generally less expensive assets, though not always.

Investor psychology and the most popular mutual fund of all time

There’s the popular example of this with the Peter Lynch Fidelity Magellan Fund. It was the most successful mutual fund of all time, earning 29.2 percent annualized returns from 1977 to 1990.

Yet the average person who invested miraculously managed to lose money.

How could this happen when it earned almost 30 percent annually?

When the environment was favorable toward good investment returns and the fund’s results were great, people got excited about buying in and inflows went up.

Nonetheless, when it had spells where it did poorly people got scared and sold out of it.

This behavior naturally led to buying toward the relative tops and selling at the relative bottoms. Even the very high annual returns couldn’t compensate for the poor timing of inflows and outflows that are naturally a function of human bias and emotion.

Nonetheless, there is still some rational basis behind this. When people need to liquidate assets to meet their payments it’s usually when things are bad. This exacerbates the issue as they tap into investments to meet their obligations, selling at the worst times possible.

When things do well, people look at the past and extrapolate that it’ll continue to be that way going forward. When things go poorly, people assume that it’s a bad investment or bad fund.

Generally, when markets go down it shouldn’t be thought of in terms of “this is a bad market to be in” but rather “this is a cheaper market”, and vice versa.

Even if you feel losses, it should ideally not affect how you run your portfolio or trading book. If strategies were easy to live with, they’d likely be arbitraged away nearly completely.

Confirmation bias

Investors are always against the issue of confirmation bias.

People prefer to see evidence that supports their current beliefs versus those that question it. Among many applications, this is why political news programming that tilts toward a certain partisanship is so popular. It’s emotionally comforting to hear things that support one’s own deep-seated beliefs.

Almost everyone is susceptible to confirmation bias to an extent. In fact, if there’s one thing most traders will admit to, it’s that they search for things that support the positions they’re already in.

There are other matters like blind spot bias (i.e., not knowing what you don’t know) and sunk cost issues (i.e., a cost that has already been paid and can’t be recovered).

One can get better at catching themselves doing this over time.

Being naturally curious helps. And always remembering that you’re looking for the best answer possible, not just something you can come up with in your own head. Even if you do have the best answer (though the odds are against you) you can’t be sure until you’ve conferred with those who are informed and credible about whatever you’re trying to understand.

And while being open-minded helps, you also have to be discerning about who’s believable and worth asking. (And of course hopefully not overweighting those who already share your opinions).

Backtesting versus Real-time

If you look at how a strategy performed over time, it’s easy to look at all the twists and turns dispassionately to help you see how you might have performed had you done it in real-time.

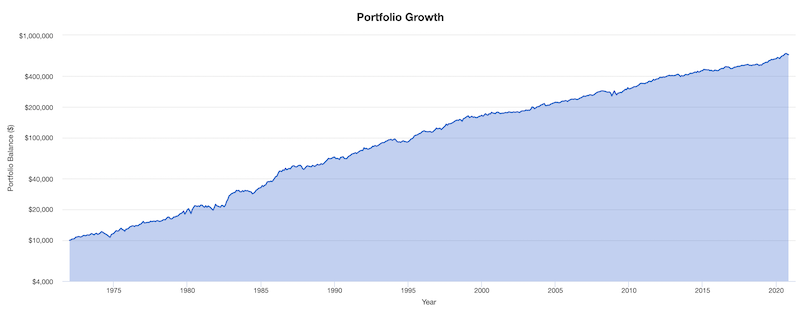

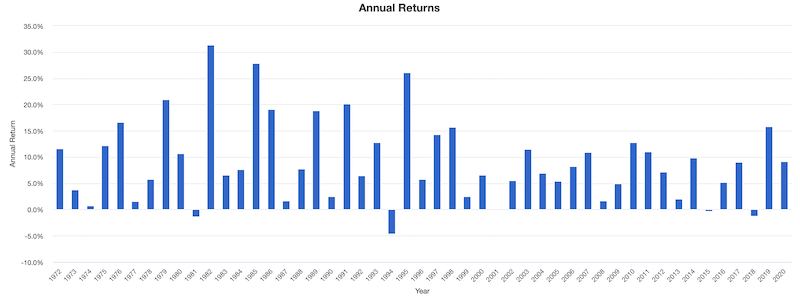

For example, the graph below shows the progress of a basic balanced portfolio strategy containing a 30/60/10 mix of stocks/bonds/gold since 1972.

(Source: portfoliovisualizer.com)

You see a nice fairly steady trend going from the bottom left to the upper right just like any investment strategy. From 30,000 feet, looking at 50-ish years of history plotted on one graph, it doesn’t look too shabby.

Moreover, it rarely had a down year compared to a lot of up years. And the down years were not very deep.

But all those bumps and squiggles can represent painful periods along the way depending on how that strategy was pursued. (Note that the returns of such a strategy are not likely to be what they were due to all asset returns being lower.)

There are plenty of “-2 standard deviation events” over weeks and months against a long-term positive observed mean.

Looking at the performance, it’s easy to view all the moderate bumps as simply inevitable statistical fluctuations of the strategy and be rational about it.

It’s an entirely different thing to actually put it on and live through a strategy in real time, even something with the general quality of a 0.60 Sharpe ratio.

In real life, we experience the months, weeks, and days, and sometimes hours or minutes that add up to a period that we feel could have been better.

A bad day during a drawdown can make something feel like it’s fundamentally off with a portfolio’s construction. This is against the backdrop that you know a positive expected value strategy has only a little bit better than a 50 percent chance of going in your favor on any given day.

During drawdown periods, it might seem like time slows and you’re losing money on a majority of the days (even when you likely aren’t).

You will lose in both up and down markets in a variety of ways. That’s of course part of the point of building a balanced and well-diversified portfolio.

Drawdowns are inevitable, but it always will make you look at the process or strategy you believe in and the parts that it makes up and wonder if something is broken. Even if the long-term evidence and intuition is still intact.

The realistic goal isn’t to completely turn into a robot, but adverse psychological swings can be ameliorated by taking actions like reducing your position sizes (limiting concentration) and limiting your use of leverage.

Setting yourself up to recognize your own biases, minimizing them, and profiting from those of others (e.g., having to sell when times are bad) is the general idea.

This is accomplished by measuring how much risk you take (most underestimate how much risk they’re taking), really understanding what you hold in your portfolio, understanding the evidence behind doing what you’re doing, and understanding how it may behave in the short term.

Successful strategies over the long-term

Strategies that are successful over the long-term tend to have one or both things going for them:

i) They compensate market participants for taking risk

ii) They take advantage of a behavioral bias or others’ error(s) in some way

There’s always somebody else on the other side of the trade. They may be doing it out of tastes, constraints, biases, prudent risk management (or to take more risk), and so on.

It’s also possible that everybody involved can win in the sense of getting what they want – after all, that’s why they enter into the trade in the first place.

For example, if somebody wants to buy an option to hedge risk, then a market maker might sell it to them. If it’s a put option, the market maker might want to hedge the risk of the uncovered put option by selling shares of the underlying to be delta hedged.

To sell shares short, the market maker has to borrow them from somewhere (i.e., someone who owns them).

The party who owns them will receive some compensation for lending them out. Shares can be lent out multiple times, a process by which helps increase liquidity in the market, tightening spreads, and doing the small part in helping lower transactions costs for all participants in that particular market.

In other words, everybody can win in some part.

Even if there are persistent behavioral biases in that market, that doesn’t mean prices get out of whack enough to the point where you can profit off them.

Too many casually say or show that “investors are irrational” and automatically think it could provide arbitrage opportunities to exploit.

It’s of course possible that we have many different systematic behavioral biases. But, alas, prices still don’t reflect them on net.

There is of course the academic literature that says such biases do get embedded in prices.

But why don’t they get arbed away?

Much of the answer is probably inherent in the psychology we’re talking about. And if you want to be technical, even with the existence of rational arbitrageurs, this isn’t going to take these strategies all the way to zero.

Risk is still involved. So, if you’re long a “low P/E stocks” portfolio against a short “high P/E stocks” portfolio to capture the value factor along that dimension, this isn’t likely to get arbed away completely.

Strategies that genuinely provide strong or at least reasonable risk-adjusted returns can be very hard to stick to long term.

In a way, it’s a paradox. They exist because they are hard to stick with.

No risk premium (i.e., returns) means no pain. You can’t just hang out in cash, so you have to take on risk, which means dealing with pain from time to time.

Drawdowns in trading are unpleasant but unavoidable. It’s simply necessary to help achieve your goals.

Wading through drawdowns is simply a necessary part of adding value (assuming your strategy or strategies are effective). Many things work or exist because others aren’t willing to tolerate the pain.

Losing unconventionally

For those who have equity-dominated portfolios, most everybody wins or loses together. Both institutional and retail investors have high betas/correlations to the stock market.

It doesn’t make losing money any worse per se, but it can help in some form if everybody else is in the same boat.

On the other hand, if you’re investing in liquid alternatives strategies or risk parity or anything that we might have covered here (tail risk hedging) or here (ways to reduce risk) that is a bit more off the beaten path, you’re basically on your own.

When tough times hit to a strategy that is uncorrelated to traditional asset classes and doesn’t necessarily depend on economic performance, then tough times can often appear to come out of nowhere.

All you can do is root for the process or strategy to go back to what it has delivered historically.

Having no explanations beyond some basic “strategy X is down Y standard deviations” is much like how it goes when pursuing independent strategies.

And the more independent the sources of returns, the better it generally is, even though it can make explaining and living through the difficult times much more difficult.

Sometimes, of course, you do have easy explanations, such as the 1999-00 tech bubble, and so on that explains a big dislocation and big movements in the prices of virtually everything.

Even if you have a strategy that works 60 percent of the time (very good), then 40 percent of the time you’ll still be asking yourself why the strategy or process isn’t doing as well.

But the least you know is that when you create something that wins 60 percent of the time at reasonable risk – and the extent of the wins exceed the extent of the losses when it does lose (i.e., the distribution of outcomes is favorable) – then you want to own it.

Those who don’t short and pursue long-only strategies will inevitably have the same issues of lagging a benchmark when they tilt the portfolio toward securities they like and away from those they don’t.

In a bull market like 1998-2000 version where speculative securities did great and “value” securities less so, it may lag behind a benchmark but still be up overall.

In a type of market neutral portfolio like liquid alternatives, you might actually be losing money because your beta to the market is probably zero, or effectively zero over the long term. In such a case, a bull market in stocks doesn’t help you.

And when you do win with market neutral strategies, it is generally independent of what the market is doing. This, of course, is naturally the point of pursuing these strategies in the first place.

Some long-only strategies can suffer from the issue of not being differentiated enough and are too close to the index to really matter.

But many traders and investors would prefer to lag in relative terms (underperforming an equity benchmark) rather than absolute terms (being market neutral), and therefore naturally gravitate toward high correlations to equities.

Moreover, some investors – e.g., mutual funds, pension funds – can only take traditional long positions and have limited use of leverage.

There is value in both “long/short market neutral” and “long-only tilting” approaches.

However, being able to go long and short results in a more efficient use of capital because it can exploit the short side of various factors and help diversify better across many different strategies.

Doing something that works long-term, but uncorrelated and different that you can stick with at a size that matters is the idea. The different part may not be easy to handle, but that’s part of the bargain.

Stories or ‘easy explanations’ about a strategy’s lack of efficacy

Nobody should feel compelled to get out of a strategy just because a -2 standard deviation event occurred.

Still, in rough patches, people will tend to come up with stories or explanations for why something that has worked for 50+ years that has strong economic logic and robust backtesting may no longer work.

And we hear about this all the time, such as the average hedge fund underperforming a representative benchmark for various reasons – e.g., mistimed flows or people piling in when things are good and getting out when things are bad.

The general idea is that sticking with a process or strategy for the long term is harder than one might otherwise think. This is a good thing, as there’s a significant long-term payoff if you can, even if it’s not easy to do.

Trader psychology at higher levels of risk

The psychology of sticking with a process is harder at higher levels of risk.

At higher risk, both the good times and bad times will be bigger, which makes it more difficult to deal with.

If a trader or hedge fund (or whatever the vehicle) is running a strategy at 20 percent targeted annualized volatility – more than the US stock market – that is relatively aggressive.

Being down two standard deviations at 20 percent is a lot different from being down two standard deviations at 5 to 10 percent, though on a percentage basis it’s the same.

If for some reason the strategy needs to be run at higher volatility, but the “psychology issues” are too much, you could simply keep more of the allocation in cash.

You could run the same strategy at half the volatility. Mathematically this cuts the dollar risk in half.

But despite all that, the real world experience of being down at a higher volatility is harder than being down at lower volatility because of the absolute losses involved.

Targeting higher risk strategies is accordingly not for everyone.

Knowing when to adjust and when not to adjust

For any drawdown, there’s always the pressure to change or do something. But a lot of investing and trading is simply waiting around in the sense of not touching a portfolio when you don’t need to. What you don’t do is just as important as what you do.

Even with the rise of cheaper or free commissions, trading costs are still a real thing with the price spread and limited size and liquidity in many types of markets.

During the 1999-00 tech bubble, a common critique of those sitting around watching the “new economy” stocks fly up while sticking with their “old economy” “value” stocks is that the old ways of measuring value no longer applied. Or even worse, that price wasn’t that important.

Instead of the traditional metrics like price-to-earnings (P/E) and price-to-book (P/B), more important were things like website clicks. But those clicks need to translate into revenue and do so in excess of the costs to have a sustainable business.

Assets are fundamentally worth how much cash they earn over their lifetime discounted back to the present (see Apple as an example). That fundamental reality hasn’t changed.

Moreover, some metrics don’t have much data behind them on which you can derive evidence over decades or centuries.

When traders and investors test out strategies they typically backtest them to see what kind of empirical support their ideas have.

Nonetheless, if you ran a price-to-website clicks type of backtest back in 1999, the data over the past five years would have shown the returns to be phenomenally good.

But that’s not a good way to apply quantitative finance.

In general, any time you are trying to use the past to inform the future and the past is not a good representation of what the future will be like you are bound to have a problem.

Other matters or factors to consider

There can be other aspects outside strategy itself that lead to mediocre performance, which in turn lead to the “psychology stuff”.

Being too big

This isn’t an issue for individual investors, but it can become an issue for institutional investors and occurs at various points depending on the strategy, market, and so on.

You never want to become too big of a part of your markets. And past a point, transactions costs increase in a non-linear way.

But being too large doesn’t imply higher odds of large drawdowns.

It just means they won’t be able to generate the type of returns as expected over the long term. The larger you become, the more of the market you are. That sets up the potential to be squeezed.

This is why a large conglomerate like Berkshire Hathaway is heavily limited to only the largest and most liquid stocks and other assets.

Diversification

The basic act of diversifying your portfolio can help alleviate drawdowns and ease the worry over your portfolio.

This can mean moving out of only stocks and into quality fixed income, liquid alternative strategies, and other ways of reducing risk.

We’re also in a low interest rate world, which carries through into all asset classes. This can behaviorally force more investors into equities despite their lower than normal returns.

The goal, generally speaking, is to find sources of return that aren’t correlated with traditional markets, asset classes, or each other. For institutional investors, this comes with the additional caveat of being able to deploy these strategies at scale.

Window dressing

While this is not that relevant to individual investors or even a big part of trader psychology itself, it is relevant toward perception, or influencing others.

For example, many investment funds that have to market to outside clients will get rid of some investments after period of poor performance and add investments after good performance.

Accordingly, when the quarterly filing is released (e.g., 13-F and the like) – for those subject to them – a quick glance at it seems to show a group of holdings that seem to be doing well.

This is known as window dressing.

The same goes for fund of funds investors. The name is as it sounds – they’re investment funds that invest in other investment funds. These institutions invest in various investment managers and market a diversified product to other investors.

The goal of fund of funds is to market the track record of their current managers. In other words, what would your portfolio look like if you invested in the set of managers you have today?

Clearly, this shows survivorship bias. Managers, even if they are otherwise great but going through a dry or rough patch, might be dumped in order to show a better set of performance. This is silly, but it does happen.

The basic idea is that if one is showing prospective clients the track record of their current managers (naturally a backward-looking metric), then there will be a bias to get rid of any through difficult times and chase after winners ex-post.

Drawdowns without catalysts

Sometimes bad events in a portfolio have a major obvious reason, like the tech bubble, 2008 financial crisis, and so on.

And sometimes they don’t.

By being market neutral with some strategies – i.e., with liquid alternatives – and targeting a relatively consistent level of volatility, you should be able to create a return stream that is less dependent on macro events, volatility in other asset classes, and more consistent in its own level of volatility.

These types of portfolios also generally don’t have large, concentrated positions. So whatever happens with one position shouldn’t have much of an effect on the entire portfolio.

As a simplified example, if you own something and it’s one percent of the portfolio and it goes to zero overnight, then that’s still just a one percent drag on your portfolio.

You don’t get the same terrible lows or quite the big highs as a traditional concentrated portfolio.

Done well, the upside capture relative to the downside is also superior as well, with a host of other benefits, including lower left-tail risk, lower drawdowns, shorter underwater periods, and a host of other benefits.

Knowing what you actually own

When a market, asset class, or individual stock or security has a bad run, you at least know exactly what you’re betting on.

It may or may not be a good bet, but it’s straightforward to understand what exactly you’re doing.

In a more market neutral strategy, like a liquid alternative, it can be hard to wrap your head around what exactly you own.

That’s also part of the point of owning something that has a positive expected return but is largely uncorrelated to other mainstream assets and asset classes.

To pick as an example, if you have an equity market neutral allocation, your general goal is to get a diversified set of stocks to own that include the ones that are:

– cheaper

– have improving fundamentals

– lower risk

– own higher quality assets

– have high margins

– strong cash flow…

…and shorting their opposites.

The portfolio will change over time, but the idea remains the same. How it performs is harder to visualize than the turnaround of something like an individual stock or market.

But that’s the general idea of how to produce positive expected returns over the long term that doesn’t look like other processes, strategies, or assets you already have in your portfolio.

A trader with a more conventional discretionary stock picking strategy gets to say something like – “We own these 27 stocks. Five of them did poorly over the past few months for reasons X, Y, and Z, but we still like them because of A, B, and C.”

Maybe it’s a good story or it’s not a good story, but it’s simple and easy to understand.

Not overreacting

As mentioned earlier, trading is not an easy pursuit for those who are impulsive and whimsical, as they will tend to do the opposite of what they should do – i.e., they get out or rip things up when obstacles are encountered and going too far in the other way (e.g., buying expensive securities) when things are good.

If you have a strategy that generates profit 60 percent of the time on a monthly timeframe, it’s probably a pretty good strategy assuming relatively normal distributions.

Don’t inappropriately extrapolate the past

If something is losing it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a bad strategy.

Let’s say you have the above-mentioned “60 percent success rate [monthly]” strategy above. It’s no different from flipping a 60-40 biased coin to come up heads.

But imagine the first flip came up tails (the 40 percent probability outcome).

You might think that having that losing period means that one could be less likely going forward (because one already happened). Or it could make you doubt your odds are as high as they are in the first place.

But naturally, what’s the expected outcome going forward?

It’s, of course, 60-40 and nothing else, and that’s what you should be betting on going forward until the evidence or logic changes.

A matter of value

Value investing has been a painful experience for many, betting on cheaper companies to outperform more expensive ones.

Value is fundamentally a bet that prices of securities inappropriately extrapolate current prospects.

Better companies should be priced higher versus their fundamentals and worse companies should be priced lower.

Sometimes prices correctly reflect this information. And sometimes it’s hard to know given the range of unknowns are always high relative to the range of knowns.

It’s also why it’s difficult to have strong conviction in trading. Almost nothing is a no-brainer.

Unlike a high-quality government bond, where you know how much you’re going to get and when, you don’t know how much you’ll get from a stock precisely. As a shareholder, you get whatever the company produces after everyone else has been paid relative to your share of the company.

Stocks are also a reflection of discounted present values. For many companies, the perception of reality is more important than what reality actually is because of this discounting process that goes out decades.

Moreover, even if something looks expensive, sometimes stocks underreact to all the information that is known. In other words, what looks expensive can actually be a good deal.

Value wins more than it loses. But there are times when cheap companies aren’t actually cheap enough versus the expensive ones and prices don’t cooperate. Naturally it’s at these times that value can fail.

Over the long-term, value works well. But the price of anything is just the amount of money and credit spent on something divided by its quantity.

That can be a function of a variety of different things outside of value considerations.

Amazon stock fell 94 percent during the 1999-00 tech bubble crash despite customers, revenues, and other important internal metrics increasing.

Part of these big drawdowns (that don’t have much to do with the fundamentals) are that a lot of people have to sell assets to meet their obligations. This causes many stocks to fall a lot in relation to their fundamentals.

Even if value stocks fall in relation to more expensive stocks, it doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s an issue with value itself. It could mean value investors are rebalancing their portfolios into even cheaper stocks.

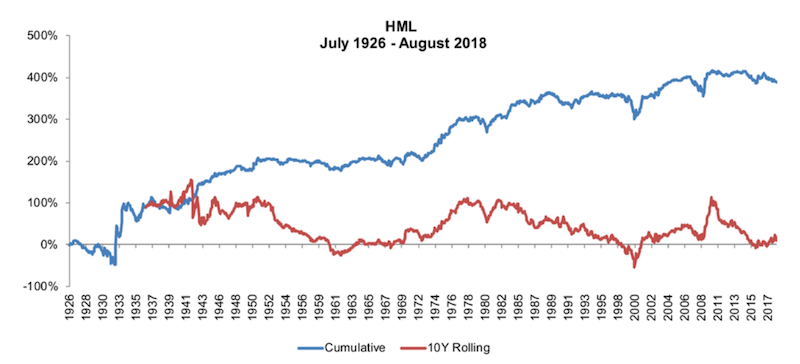

A long-term drawdown in value can occur. There have been 10-year underwater periods in value before (see below; red line), taking a standard “long low P/B” versus “short high P/B” portfolio since 1926.

Such longer drawdowns are still consistent with their Sharpe ratios. But during this drawdown, it still doesn’t mean you now own very cheap longs and very expensive shorts.

If that type of strategy is down over the course of several years, you will naturally own a very different portfolio relative to how it was in the past. Your portfolio wouldn’t necessarily be better – i.e., a higher “value spread” – but it would be different.

Trusting the process

If you have a belief in a certain process, you should examine why you have it on in the first place – what is the long-term evidence and economic intuition as to why it should make sense?

Not every strategy or market will go up in a straight line.

To highlight a process most are familiar with if they’ve been trading or investing for some time, when equities go down, it’s not that equities are “broken”.

They are probably cheaper. Though that has nothing to do with how they’ll continue to perform in the short- or medium-term.

It’s also a reminder of why we get paid to own equities – they have plenty of price risk associated with them being long duration assets.

Navigating through drawdowns is a major way that you add value to yourself, family, clients, or whoever you manage your portfolio for.

If you’re pursuing relative value strategies that are in a downturn, you shouldn’t be nervous that the future is bad for cheap, high quality (e.g., high margins, high cash yields), high momentum, lower risk assets and bright for expensive, low quality, low momentum, higher risk assets. Nor can you be sanguine that adverse trends will reverse quickly.

Trading, like all jobs, involves some level of stress. And everybody is wired differently to handle certain amounts of it up to a point.

With respect to trading itself, it can be your process or strategy, and/or it can be the tactics you use to get there.

If small changes in a portfolio cause stress, then you might be overleveraged, too concentrated, or have other issues impacting your portfolio if the drawdowns are too painful to endure.