The Covered Call: How to Trade It

The covered call – sometimes called a “buy-write” – is a common trading strategy used among all types of market participants, from day traders to institutions that often hold securities for years.

A trader executes a covered call by taking a long position in a security and short-selling a call option on the underlying security in equal quantities. (Each options contract contains 100 shares of a given stock, for example.) This is most commonly done with equities, but can be used for all securities and instruments that have options markets associated with them.

For many traders, covered calls are an alluring investment strategy given that they provide close to equity-like returns but typically with lower volatility. This is because even if the price of the underlying goes against you, the call option will provide a return stream to offset some of the loss (sometimes all of the loss, depending on how deep). Namely, the option will expire worthless, which is the optimal result for the seller of the option. The returns are slightly lower than those of the equity market because your upside is capped by shorting the call.

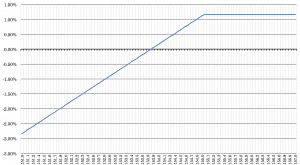

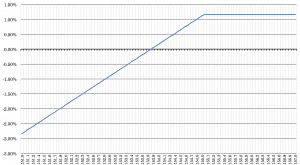

In terms of an options profit/loss diagram, the call option strategy appears as follows:

Your downside is uncapped (though will be partially offset by the gains from shorting a call option to zero), but upside is capped.

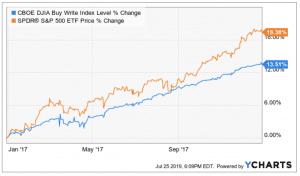

We can see that in times of stress or downside volatility, the buy-write index (CBOE’s BXD; blue line) performs better than the S&P 500 (orange line).

In years like 2017 when volatility is low but returns are above average, the buy-write index will perform worse than the S&P. Options premiums are low and the capped upside reduces returns.

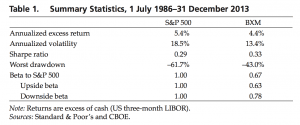

Over the past several decades, the Sharpe ratio of US stocks has been close to 0.30 while the Sharpe ratio of various covered call indices has been slightly higher at around 0.33, with lower drawdowns and a lower beta to the stock market.

The covered call strategy is popular and quite simple, yet there are many common misconceptions that float around.

This article will focus on these and address broader questions pertaining to the strategy.

For example, when is it an effective strategy? When should it, or should it not, be employed? What are the root sources of return from covered calls?

Covered Call: The Basics

To get at the nuts and bolts of the strategy, the returns streams come from two sources:

(1) equity risk premium, and

(2) volatility risk premium

You are exposed to the equity risk premium when going long stocks. Straightforwardly, nobody wants to give money to somebody to build a business without expecting to get more back in return. Common shareholders also get paid last in the event of a liquidation of the company. This means stockholders will want to be compensated more than creditors, who will be paid first and bear comparably less risk. Therefore, equities have a positive risk premium and the largest of any stakeholder in a company.

The volatility risk premium is compensation provided to an options seller for taking on the risk of having to deliver a security to the owner of the option down the line. Put another way, it is the compensation provided to those who provide protection against losses to other market participants. It is very similar to insurance, or the notion of getting paid to manage somebody else’s risk.

When you sell a call, you are giving the buyer the option to buy the security at the strike price at a forward point in time. The call option buyer’s upside is unlimited but his downside risk is capped, and that trader pays you a premium for absorbing that risk for them. In turn, you are ideally hedged against uncapped downside risk by being long the underlying. (If not, that is an uncovered or “naked” exposure.)

What you are doing when entering into a covered call is “covering” the potential that the shares will need to be delivered in the future. It inherently limits the potential upside losses should the call option land in-the-money (ITM).

When you execute a covered call position, you have two basic exposures:

(1) You are long equity risk premium, and

(2) Short volatility risk premium

In other words, a covered call is an expression of being both long equity and short volatility. It effectively reduces a portfolio’s exposure to the underlying security while also adding a negative volatility exposure on top of that.

Options have a risk premium associated with them (i.e., they are priced more than they should be) because the implied volatility backed out from the options pricing is more than the ex ante expected volatility of the underlying security.

This has to be true in order to make a market – that is, to incentivize the seller of the option to be willing to take on the risk. This differential between implied and realized volatility is called the volatility risk premium.

Modeling covered call returns using a payoff diagram

Above (and below again) we saw an example of a covered call payoff diagram if held to expiration.

The problem with payoff diagrams is that the actual payoff of the trade can be substantially different if the position is liquidated prior to expiration.

This is similar to the concept of the payoff of a bond. Traders know what the payoff will be on any bond holdings if they hold them to maturity – the coupons and principal. Given they also want to know what their payoff will look like if they sell the bond before maturity, they will calculate its duration and convexity.

Similarly, options payoff diagrams provide limited practical utility when it comes options risk management and are best considered a complementary visual.

Moreover, when calculating a trade’s profit/loss expectations, it should always be done in terms of the expected value calculations. An options payoff diagram is of no use in that respect.

Likewise, you will often see traders think they have a high risk/reward trade just because of where they locate their stop-loss and take-profit levels. For example, if someone goes long a stock at $100, puts their stop-loss at $90 and take-profit at $130, they might think that they’re entering into a 3x reward/risk trade because their potential profit is $30 per share but their loss is limited to $10.

The basic reality, however, is that a stock trading at $100 is much more likely to hit $90 before it reaches $130. Thus it’s not actually a “3x reward/risk” trade at all and it would be erroneous to think of it that way.

Does a covered call provide downside protection to the market?

An investment in a stock can lose its entire value. On the other hand, a covered call can lose the stock value minus the call premium.

Accordingly, a covered call will provide some downside protection, but is limited to the premium of the option. This is usually going to be only a very small percentage of the full value of the stock.

For example, if you were to take an at-the-money (ATM) covered call on the S&P 500 for maturity in one week, the call premium as a percentage of the value of the underlying would be 0.60 percent. Given the S&P 500 is a very broad index with no “idiosyncratic risk” (because it’s considered the market itself) and the maturity is very short, the premium is low.

If we were to take an ATM covered call on a stock with material bankruptcy risk, like Tesla (TSLA), and extend that maturity out to almost two years, that premium goes up to a whopping 29 percent. Therefore, if the company went bankrupt and you were long the stock, your downside would go from 100 percent down to just 71 percent. The downside, of course, is that an ATM option doesn’t allow you to participate in any prospective upside. Whether it’s worth cutting your downside by 29 percentage points to forgo any upside would depend on your perceptions of the implied volatility of the option relative to its likely realized volatility, the expected value of the trade, its expected value relative to other trade ideas, and its influence on the broader portfolio.

Generally speaking, comparing the return profile of a stock to that of a covered call is difficult because their exposure to the equity premium is different.

An in-the-money (ITM) call option will act similarly to owning the stock outright depending on how far ITM it is. An ATM call option will have about 50 percent exposure to the stock. An OTM call will have less than 50 percent exposure to the stock depending on how far OTM is.

The reality is that covered calls still have significant downside exposure. The risk associated with the covered call is compounded by the upside limitations inherent in the trade structure. Therefore, from an expected value and risk-adjusted return perspective, the covered call is not inherently superior to being long the underlying security. It’s entirely dependent on one’s objectives and shouldn’t be pursued naively.

According to a study completed by Standard and Poor’s and the CBOE on the covered call strategy versus standard equity exposure done over a 27.5-year period (July 1986 to December 2013), the upside beta of the covered call strategy is 0.63 against a downside beta of 0.78. (The upside and downside betas of standard equity exposure is 1.)

Therefore, while your downside beta is limited from the premium associated with the call, the upside beta is limited by even more.

To sum up the idea of whether covered calls give downside protection, they do but only to a limited extent. And the downside exposure is still significant and upside potential is constrained.

Do covered calls generate income?

Does selling options generate a positive revenue stream? Yes. But that does not mean that they will generate income. Income is revenue minus cost. The premium from the option(s) being sold is revenue. The cost is associated with the option’s future realized volatility relative to its implied volatility (i.e., if realized volatility comes out high than implied volatility and to what extent) and other fees (commissions).

When you sell an option you effectively own a liability. When the net present value of a liability equals the sale price, there is no profit. In other words, the revenue and costs offset each other.

Commonly it is assumed that covered calls generate income. But there is no income generated from a covered call unless the option’s implied volatility is sold at a level above the stock’s expected volatility.

Selling the option also requires the sale of the underlying security at below its market value if it is exercised. This risk creates the possibility of incurred costs that could be higher than the revenue generated from selling the call.

For example, let’s say you own a stock trading at $100 and sell a call with a $120 strike price for a $5 per share premium.

If the stock trades for $120 or less by expiration, the sold call option incurs no costs beyond the commission required to complete the transaction. Therefore, in such a case, revenue is equal to profit.

However, if the stock were to sell at $140 by expiration, the costs would be $20 per share. The revenue is the $5 per share (the premium), leading to a net income of minus-$15 ($5 per share minus $20 per share). The cost of the liability exceeded its revenue.

As part of the covered call, you were also long the underlying security. This means, in effect, the cost of the liability might be viewed as being “cancelled out”. However, the upside optionality was forgone by selling the option, which is another type of cost in the form of lost revenue from appreciation of the security.

Does a covered call allow you to effectively buy a stock at a discount?

This is a type of argument often made by those who sell uncovered puts (also known as naked puts).

Namely, if you want to buy a stock but want it at a cheaper price, then the idea is to sell a put at the price you’d be willing to purchase it. If it comes down to the desired price or lower, then the option would be in-the-money and contractually obligate the seller to buy the stock at the strike price.

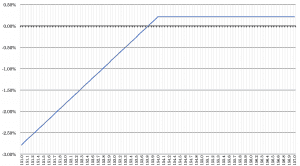

However, it’s commonly used by covered call proponents as well. A covered call is essentially the same type of trade as a naked put in terms of the risk and return structure. Their payoff diagrams have the same shape:

Covered call

Naked put

The logic follows along the lines of, if a stock you want to own is currently $100 per share but you would want to own it if it fell to $90, you would sell a put at a $90 strike and collect a premium of, for example, $2 per share.

If the stock falls below the $90 strike price by expiry, then the seller (the naked put writer) would be obligated to buy the stock at that price. Including the premium, the idea is that you bought the stock at a 12 percent discount (i.e., $100 minus $90 minus $2). On the other hand, if the option expires worthless, then you collect the $2 premium and this is pure income.

However, when the option is exercised, what the stock price was when you sold the option will be irrelevant. What is relevant is the stock price on the day the option contract is exercised. If the strike price is $90, but the option is exercised on a day when the price of the underlying is $70, then $90 no longer seems like a very good deal.

The loss is now $18 per share ($70 minus $90 plus the $2 premium). The $2 premium is little in the context of that loss. Buying at $70 is unfavorable to you because you’re now losing $20 per share and only gaining $2 in premium from the option buyer.

Moreover, and in particular, your opinion of the stock may have changed since you initially wrote the option. If the stock was trading at $100 when you sold the put but it is now at $70 (30 percent lower), you might feel that the fundamental value of the stock is different now compared to when you entered into the contract.

Namely, stipulating a security’s future fundamental value today is not always a good idea. As time goes on, more information becomes known that changes the dollar-weighted average opinion over what something is worth. The option seller, however, has locked himself into transacting at a certain price in the future irrespective of changes in the fundamental value of the security.

Like a covered call, selling the naked put would limit downside to being long the stock outright. If a $100 stock with a naked put at a strike of $90 is set with a premium of $2, if the stock falls 30 percent, the loss is 18 percent. If the stock settled at any price above $90 by expiry, the gain is $2.

This would be no different than owning the underlying stock while having sold a $90 strike call with a premium of $2. If the stock falls from $100 to $70, the loss would be 18% and any price movement at $90 or above would provide a return of 2 percent.

Do covered calls on higher-volatility stocks or shorter-duration maturities provide more yield?

This is another widely held belief. Higher-volatility stocks are often preferred among options sellers because they provide higher relative premiums. Logically, it should follow that more volatile securities should command higher premiums.

Selling options is similar to being in the insurance business. If you are selling car insurance to a 20-year driver with an extensive accident and infraction history driving a $50,000 car you are going to charge a higher premium relative to a 45-year-old driver with a clean history and $10,000 car. Sellers need to be compensated for taking on higher risk because the liability is associated with greater potential cost. The cost of two liabilities are often (very) different.

Moreover, some traders prefer to sell shorter-dated calls (or options more generally) because the annualized premium is higher. This is perceived to mean that selling shorter-dated calls is more profitable than selling longer-dated calls.

On the S&P 500, selling 52 ATM one-week calls would net about 5x more revenue than selling one ATM one-year call. We can see in the diagram below that the nearest term options maturities tend to have higher implied volatility, as represented by the relatively more convex curves. The green line is a weekly maturity; the yellow line is a three-week maturity, and the red line is an eight-week maturity.

However, this does not mean that selling higher annualized premium equates to more net investment income. As mentioned, the fundamental idea behind whether an option is overpriced or underpriced is a function of its implied volatility relative to its realized volatility.

Similarly, if you were looking to short-sell a stock, you would not go by a stock’s price and whether it “seemed high” but rather whether the stock was expensive relative to its fundamental value. Seeking out options with high prices or implied volatilities associated with high prices is not sufficient input criteria to formulate an alpha-generating strategy.

Is theta (time) decay a reliable source of premium?

It is common knowledge that an option’s value declines as time passes. This is known as theta decay. (Theta is the “Greek” associated with assessing the time impact on an option’s value. Namely, it represents the amount by which the option’s value will decrease each day, usually expressed as a negative number.)

Options do lose value over time, which is positive for the option’s seller. However, things happen as time passes. Specifically, price and volatility of the underlying also change.

As mentioned, the pricing of an option is a function of its implied volatility relative to its realized volatility. If implied volatility is higher relative to realized volatility, the option’s seller makes a profit (on the option itself). If implied volatility is less than its realized volatility, the option’s buyer makes a profit.

Disregarding the effect of realized volatility on an option’s price often leads to the erroneous conclusion that theta decay will be a strong source of investment income. Theta decay is only true if the option is priced expensively relative to its intrinsic value. If the option is priced inexpensively (i.e., implied volatility lower than realized volatility), then theta decay works against the seller.

Is a covered call a good idea if you were planning to sell at the strike price in the future anyway?

For example, let’s say you own a stock trading at $100 per share. If you would sell the stock at $120, does it make sense to sell a call option at a 120 strike to get paid for what you plan on doing in the future anyway?

In theory, this sounds like decent logic. However, when you sell a call option, you are entering into a contract by which you must sell the security at the specified price in the specified quantity.

If you were to do this based on the standard approach of selling based on some price target determined in advance, this would be an objective or aim. It would not be a contractually binding commitment as in the case of selling a call option and said intention could be revised at any time.

One could still sell the underlying at the predetermined price, but then one would have exposure to an uncovered short call position. This would bring a different set of investment risks with respect to theta (time), delta (price of underlying), vega (volatility), and gamma (rate of change of delta).

Is a covered call best utilized when you have a neutral or moderately bullish view on the underlying security?

It is commonly believed that a covered call is most appropriate to put on when one has a neutral or only mildly bullish perspective on a market.

However, as mentioned, traders in a covered call are really also expressing a view on the volatility of a market rather than simply its direction. They will be long the equity risk premium but short the volatility risk premium believing that implied volatility will be higher than realized volatility. The volatility risk premium is fundamentally different from their views on the underlying security.

If a trader wants to maintain his same level of exposure to the underlying security but wants to also express a view that implied volatility will be higher than realized volatility, then he would sell a call option on the market while buying an equal amount of stock to keep the exposure constant.

For example, if one is long 100 shares of Apple (AAPL) and thought implied volatility was too high relative to future realized volatility, but still wanted the same net amount of exposure to AAPL, he could sell a call option (there are 100 shares embedded in each options contract) while buying an additional 100 shares of AAPL. Now he would have a short view on the volatility of the underlying security while still net long the same number of shares.

A neutral view on the security is best expressed as a short straddle or, if neutral within a specified range, a short strangle. Moreover, no position should be taken in the underlying security. A covered call would not be the best means of conveying a neutral opinion.

The only way a covered call may be the most rational way to express neutrality on the underlying is if there was some constraining force behind why you couldn’t liquidate a position in the security. In this particular case, a covered call would be an improvement on being long the underlying only, but this also now provides risk exposure to the security’s volatility and would therefore be an imperfect method of expressing such an opinion.

Conclusion

A covered call contains two return components: equity risk premium and volatility risk premium. Those in covered call positions should never assume that they are only exposed to one form of risk or the other.

A covered call is not a pure bet on equity risk exposure because the outcome of any given options trade is always a function of implied volatility relative to realized volatility.

Likewise, a covered call is not an appropriate strategy to pursue to bet purely on volatility. Adjusting one’s volatility exposure would best be pursued by buying or selling straddles (buying to go long volatility and selling to go short volatility).

The common perceptions that a covered call is a good way to generate investment income and/or limit one’s downside exposure are frequently perpetuated, but are more fallacy than descriptive of reality.

A covered call strategy can provide income, but it does to the same extent of any other trading strategy – by extracting risk premium from the market or by making directionally accurate predictions about the future price of any given security/asset or set of securities/assets.

Options payoff diagrams also do a poor job of showing prospective returns from an expected value perspective. This goes for not only a covered call strategy, but for all other forms.

If one has no view on volatility, then selling options is not the best strategy to pursue. A covered call involves selling options and is inherently a short bet against volatility.

Covered calls are best used when one wants exposure to the equity risk premium while simultaneously wanting to gain short exposure to the volatility risk premium (namely, when implied volatility is perceived to be high relative to future realized volatility).