Military War: Role in US-China Relations & Impact on Markets

Envisioning the next major military war and its impact on financial markets (and, of course, the world) is difficult, as the range of unknowns is so high. But one thing we should acknowledge is that it’s likely to be much more brutal than most would imagine.

World War II was much more deadly than World War I, as the ~25 years that elapsed between the two enabled weaponry and military technology to grow enormously.

We are now decades and decades past World War II, and a lot of weaponry has been developed confidentially. The capabilities and overall new creative ways to cause harm have grown extensively since the last time the most sophisticated weapons were used in an all-out military engagement.

The types of different warfare, and the different types of weapons systems within each, have also multiplied. While obviously nuclear warfare is scary, there are now many more forms of warfare than those known from previous global conflicts.

There’s potential warfare along various dimensions, including chemical, cyber, space, biological, among other types.

We haven’t seen these types of conflicts, so there is a big unknown as to how they could work.

What we know right now

We are in the midst of the United States and China being engaged in different types of “wars” or conflicts.

Categorically, there are five main types of wars you can have between countries, many of which we’ve done separate articles on:

i) trade and economic

ii) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military

We believe this is important as the two largest overall economies, and the two largest debt and equity markets, are increasingly butting up against each other in a quest for power.

How this progresses will have big implications for capital flows and markets. There is a wide outcome of possibilities.

Right now, it generally seems true that China will continue to grow its economy, currency, markets, technology, and military power at a faster rate than the US (and the Western, developed economies in general).

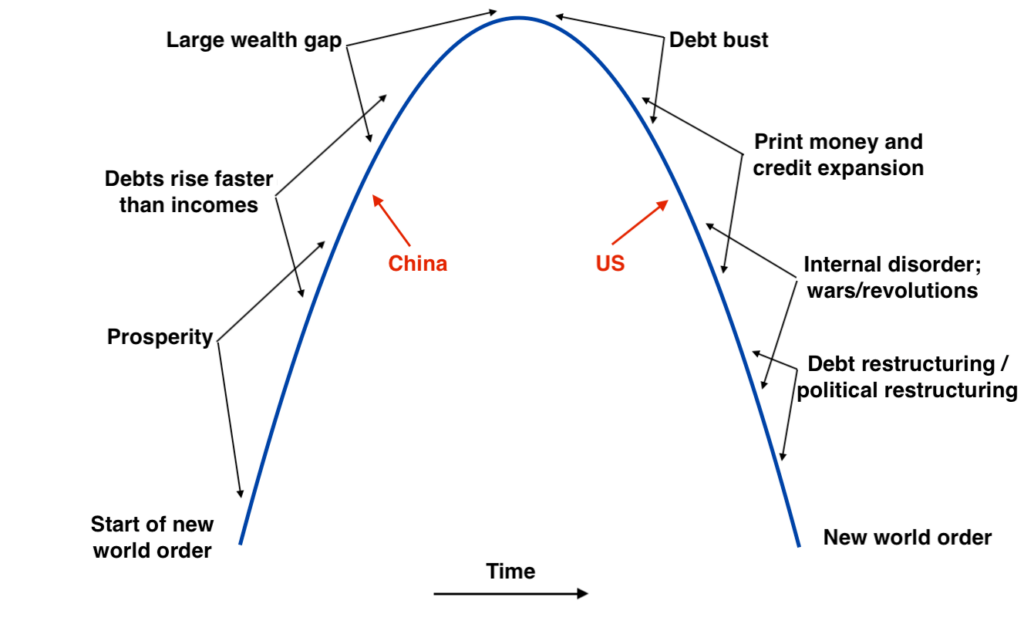

In terms of the conceptual arc of empire development, we believe China and the US are in their respective stages as displayed below.

Does that lead to a more bipolar but peaceful world or does it lead to fighting and an eventual hot war to decide what the next world order will look like?

Current hot spots

The US and China have a geopolitical conflict in the East and South China Seas. This is increasing the odds of a military conflict as each is testing the boundaries of the other.

China is militarily stronger than the US’s in these regions. The US is stronger overall, and would expect to win a broader war.

But the US would face an uphill battle in defending both of these regions that the Chinese prize having sovereignty over.

Other potential “hot spots” include Taiwan, North Korea (a wedge/buffer region between China and a US ally), and potentially India and Vietnam.

Overall, a broad-scale conflict would be tough to imagine because of the large number of unknowns.

This also includes how other countries fit into the picture and how alliances would form.

What technologies exist and what forms of warfare will be used and in what ways?

If it were to get to that point, it would be a horrible conflict that will come as a big surprise relative to the state of the world that we’re in currently. When the world is largely at peace (in contrast to, e.g., the 1939-1945 period), it’s easy to extrapolate peace going forward.

China’s improvements

China’s military capabilities are expanding rapidly. This is expected to progress even more quickly as China’s economic and technology improvements give it more capabilities in other ways. This includes progressing faster than those of the US.

It’s not out of the question that China becomes militarily superior to the US by around 2030, and even earlier in some ways.

A military war between the US and China would also include all the other various types of “wars” or conflicts – i.e., economics and trade, capital, technology, geopolitical.

All of these would also be pursued to their very maximums to inflict the greatest amount of pain. Naturally, this is done to ensure survival in the ways that countries always do.

Effectively it would be World War III.

And because of various technological advances in the ways harm can be imposed, World War III would be likely to many magnitudes more destructive than World War II, which in turn was many times more deadly than World War I.

The component of internal conflict and its influence on external conflict

Countries that suffer from internal social disorder are more vulnerable to conflict externally.

For example, in the 1930s, European countries were suffering from economic depressions and internal conflicts. This led Japan to opportunistically try to exploit the vulnerabilities of European colonies in the 1930s.

If financial resources are spread thin by domestic conflicts, that makes countries more prone to offensive moves by competitors.

If there is weak leadership in a country and/or if leadership is in a period of transition at the same time there is large internal disorder the potential for these exploits should be considered higher than normal.

Within the context of US-China relations, time is on the side of China and less so on the side of the US due to the former’s increasing improvements and the latter’s slower pace.

If there were to be a war, it would be in the interests of China to wait when it will be strong and more self-reliant. It’s in the interests of the US to have it sooner.

The internal war

How people are with each other is the biggest driver of changes in domestic conditions. It determines how they will handle the circumstances that they mutually face, and is the primary determinant of the outcomes they get.

The US, for example, has had only one civil war in its history, many severe conflicts, and several peaceful revolutions. It has great capacity to bend without breaking.

But, in general, systems and orders are at risk when the individuals within them don’t respect it more than what they want individually.

The conflicts within countries are a big driver in US-China relations.

This boils down to culture, in terms of how each side and the different factions will approach these circumstances, including what’s uncompromisable and what people are literally willing to die for than give up.

The cultures that countries have will be the biggest drivers of how people are with each other. What do Americans and the Chinese value most? How do they believe people should be with each other? This will determine how they are with each other domestically.

Both the US and China have different values, norms, and cultures that they are willing to defend.

Both sides need to understand what these values are in order to get through these differences in a peaceful way.

US culture

The US was founded on principles that value the role of the individual. This encourages its leaders to run the country with that in mind.

That means personal liberty, respect for individual creativity, grit and determination, and favoring individualism over collectivism.

These cultural values produced a more democratic decision-making process and the type of economic system the US has.

Chinese culture

By contrast, Chinese culture favors the collective interest before individual interests. Each person largely needs to know their responsibility and play that role well.

There is also more emphasis placed on respect for those senior in established hierarchies.

It’s analogous to how one might think of a sports team in terms of the basic idea. Everybody has a particular role on the team, and when run well, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There’s also a high level of respect paid to coaches and management who help to guide the players in this process.

The Chinese also broadly seek that more of the opportunities and productivity is distributed widely, out of fairness and to avoid the various “gaps” (wealth, income, values, opportunity) that often plague more economically liberalized countries.

Yet both share a lot in common

While these differences between cultures exist overall and at a general level, both Americans and the Chinese share a lot of beliefs in common.

And, of course, at the individual level, these beliefs vary widely. Many Chinese are comfortable (or prefer) living in the US, and many Americans prefer to live in China.

Moreover, if you go to other places that are ethnically Chinese, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, their ways of governance are closer to those found in Western countries than those found in mainland China.

Cultural difference in times of conflict

Even despite similarities and the wide variance at the individual level, cultural differences affect a lot.

They are especially important during times of conflict when they determine whether the sides and factions involved will choose to fight or peacefully resolve their differences.

Both the US and China need to understand each other’s values and ways of operating and realize that certain ways of doing things are culturally rooted and won’t change.

Each country will want to do what they think is best for their own country and won’t want the other side to infringe on that.

Since China began opening up the country to foreign commerce and communications in the 1980s and into the 1990s, both the US and China have worked together to make similar types of products and outcomes.

The two countries are as similar as they ever have been.

Even so, the differences in approaches between the two countries are conspicuous. This is regularly displayed at the government level and especially how the Americans and Chinese comport themselves within leadership and policymaking positions.

In the US, there are lots of conflicts within government that are brought out publicly, even to extreme levels. This includes personal animosity between public officials that go beyond policy disagreements.

Within China, disagreements are handled in private.

Some cultural differences are minor. Some are major to the point where some people are willing to die rather than give them up.

For example, most Americans value individual liberty. However, to the Chinese this isn’t as important as collective solidarity.

The Chinese government will take this to a point where they will regulate what types of media its population will consume.

This includes what types of apps and parts of the internet its population can use, literature, film and theater, instant messaging, television, radio, music, video games, and print media.

“The Great Firewall of China” blocks tens of thousands of websites. Some musicians and bands are censored as well

In the United States, most would find this to be an infringement on civil liberties and it would be up to the individual to self-regulate themselves and/or what their children consume in terms of media or entertainment.

In China, the culture makes it easier for them to accept the government’s mandates and paternalism. However, in the US, the culture would make it more likely for Americans to fight with their government over whether it’s appropriate to do what they do.

Bottom-up versus top-down

There are pros and cons to the “bottom-up” American way of operating and the “top-down” Chinese way of operating, which we won’t digress into.

But these cultural differences are deeply rooted, so one can’t expect the Americans and Chinese to act differently than they want to act.

The US can’t expect China to forfeit what it believes are the best ways of operating for its people.

And given China’s ability to grow their economy since beginning to open up in the 1980s and the culture behind making that happen, there is no chance of the Chinese giving up their values and system any more than the US will forfeit theirs.

The US shouldn’t expect to be able to make China more democratic, as it would represent a subversion of their most fundamental values and approaches toward living them out, which they will fight to protect.

This is no different than Americans and their values and their ways of living them out in the way they believe is best.

In the US, it is widely believed that democratic institutions and giving everyone an equal voice in the voting process is the most equitable way to do things.

In China, it is believed that having insightful, capable leaders making the choices is better than a system that assumes everybody has equal ability to make these decisions.

In the US the “each person has an equal voice” approach at the voting booth is considered the fairest thing to do.

However, in China a greater proportion believes that the general voting population will largely choose leaders based on entrenched support for a particular party, emotions, impulse, who they like (e.g., who’s personality they prefer, who is most like them), and what the candidates promise to give them as a way to buy their support.

A big reason why the US is on the decline in relative terms is because of its financial situation. There is not only national debt, but non-debt obligations related to pensions, healthcare, and other unfunded obligations that are many multiples of that nominal figure.

The general population is likely to choose those who will give them more money in the ways possible (e.g., direct transfers, tax cuts) without concern for where that money will come from (or how the extra debt will be financed or eventually paid).

Democracy versus autocracy

The Chinese also largely believe that democracies are vulnerable to high levels of dysfunction and anarchy when people are at each other’s throats over how to do what’s best.

These are periods where democracy is at risk of falling into autocracy to have a strong leader gain control of the situation. This was the case with Germany, Spain, Italy, and Japan (four major democracies) in the 1930s.

China also believes that its selection of leaders is more suitable to the development arc (conceptually shown earlier in this article) that takes its course over many decades or centuries.

Namely, having less turnover tends to lend itself to better strategic decision-making than having leadership turnover at a more frequent pace, which creates more tactical decision-making.

It is actually challenging for China to deal with the frequent turnover in US leadership and policies from ever-fluctuating shifts in what matters to the US voting public as shown in whom they choose to represent them.

The US population would take great offense to the idea of a president serving with no term limits, similar to what Chairman Xi Jinping may choose to do in China. However, in China, the continuity for the sake of long-term decision-making is more accepted (even though, of course, many will object to it).

With China’s emphasis on the collective, they believe that is most appropriately determined by wise leaders.

It is analogous to the type of decision-making and governance system that’s common in large companies, where top management largely guides the most important decisions being made. Sometimes top management is also in place for potentially decades.

That hierarchy is important and largely respected.

As you might imagine, it is confusing to China why its governance system is so controversial to Americans and most of the Western world when this approach is common in the private sector and many of their everyday lives.

Many Americans, business-minded or not, may look at Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett (who took control way back in 1965) as a great success story and an example of an outstanding track record of top-down leadership.

Yet almost all Americans would find it unthinkable to have the federal government run in this way, of a single strong leader installing himself to lead in a more autocratic way.

Americans and Westerners cherish the idea of elections giving them the opportunity for civic participation.

Of course, some Western companies may also be more democratic with “one person, one vote” type systems, but they are not common. And many would agree that giving everybody effectively equal power is probably not the most effective approach as it assumes everybody can make equally good decisions.

But the general idea is that there are pros and cons to each approach and that it’s imperative for both the US and China to see things through each other’s eyes as a whole. Conflicting interests and conflicting beliefs typically make it difficult to see different perspectives.

This means essentially respecting each other’s choices to do what’s right for their country or getting into a bigger, destructive engagement by fighting over what each is not willing to compromise.

US-China Economic and Political Systems

The US has a much shorter history than China, and their respective histories have shaped their cultures as well as their economic and political systems.

Some perceive that the US is more culturally right (i.e., favoring private ownerships, allowing individuals to flourish in the system, and more limited wealth redistributions) and that China is more culturally left (i.e., favoring government ownership of the means of production and more wealth redistribution to the poor).

However, these swings from one end of the spectrum to another have existed in all empires, including China. So, it’s not entirely the case that China is culturally left (or right).

The US has had swings each way, but over a history of only about four centuries (with a part of that history originally as British colonies).

Europe has a much longer history. And naturally with a longer history, there have been wider shifts to each side, and we should also expect to see this as the US’s history goes on.

Moves between “left” and “right” probably have more to do with swings around shorter-term trends than actual shifts in core values.

These shifts seem more prominent in the US because of open indications of them like protests and shifts in presidential and congressional leadership (and because the mainstream media is partisan and accentuates political topics).

But they occur in China as well, though it’s more moderated. The Chinese government restricts various types of media content and cracks down on individual dissenting behavior that it believes is disruptive to the internal social order.

Despite the Chinese government calling itself the Communist Party, capitalism inherently underlies the Chinese economy. This has helped to tie incentives with productivity, even though it’s driven in a very much top-down manner.

Instead, the cultural differences tend to manifest not in “left” or “right” or in “socialism” or “capitalism” but in the top-down and more hierarchical governance of China against the bottom-up and more non-hierarchical governance system of the US.

Neither is always good or bad. There are times when one can work well and times when the other can.

It depends on the circumstances and how people interact with each other within the system.

Both democratic and autocratic systems eventually wobble and experience failure when:

i) the system lacks the flexibility to enable these conflicts to come through without breaking the system (i.e., strong institutions, strong rule of law), and

ii) the individuals within the system value what they want ahead of the system and are accordingly willing to break laws or fight to the death to try to achieve this.

Accordingly, one of the big challenges of the 21st century will be for the US and China to share power and peacefully evolve together.

What is each country not willing to give up and where will that take them?

When we talk about military engagements, because they are potentially so dangerous and costly, they are usually provoked when a “red line” is crossed on something that can’t be compromised.

This is why a mutual understanding of the culture of each is critical for each side.

The Chinese have more respect for authority and value the role of the individual in holding up the collective.

For example, if somebody is in a superior position in the hierarchy, those in a subordinate role are expected to realize they’re in a subordinate position and respect that, and be punished if they don’t.

That is essentially the cultural predisposition and governance style of Chinese leadership.

Americans and most in Western countries place very high value on the ability to express themselves (including critical thoughts about government and political leaders) and wouldn’t want their government to stand in the way of that right.

When Daryl Morey, the general manager of the Houston Rockets of the National Basketball Association (NBA) tweeted to express support for the pro-democracy protests going on in Hong Kong, and nearly immediately pulled the tweet down, it was met with criticism from Americans of all stripes.

The US media, private citizens, and politicians criticized him for not abiding by his right to express himself. The Chinese responded by dropping NBA games from China’s state television, pulled NBA merchandise from China (including from online channels), and demanded that the NBA/Rockets organization fire Morey for his views (they didn’t).

Some Americans (e.g., LeBron James) criticized Morey, given the NBA’s interests in China could be compromised from expressing his beliefs. But most Americans sided with Morey given their support for Hong Kong and other issues going on within China.

The clash came about given the importance of free speech and expression to Americans. And also because most Americans believe that an organization than an individual is a part should not be punished for the actions of the individual.

The Chinese, however, believe that the organization should be held accountable for the actions of the individuals within it and punished accordingly. Hence the Chinese government’s response.

While this had to do with a sports league, one could imagine much larger conflicts that could potentially come out of these cultural differences.

Depending on the circumstances, China can be great friends to countries throughout the world but also countries can be turned off by their style of governance and the punishments they’re inclined to give or request for violating these norms.

Some things with China can be negotiated while others can’t be.

Different cultures and different values mean different choices

Because the US and China have different cultures and different values it means they will make different choices. That means plenty of choices that the other side probably won’t like.

For instance, on the topic of human rights, the US doesn’t like China’s treatment of Uighurs and Tibetans and China doesn’t like how the US handles some of its own human rights issues and how it carries itself in some ways in foreign affairs.

Does that mean the US should fight China on this issue, and vice versa? Or does it mean the best path is to agree not to intervene to try and impose what the other should do?

In recognition of sovereignty issues, as we explored more when covering the geopolitical conflict between the two sides, it is probably not only hard for either side to make inroads on changing the other in this matter but also likely impossible.

The testing of relative powers

In the end, forcing other countries to do things that are outside of their interests is a function of relative powers.

If one’s relative powers are uncertain, then conflict is practically inevitable in order to determine how to resolve that. Ideally this occurs without a military war or any type of war that costs lives.

However, being practical, when it isn’t clear who has power and it involves things that can’t be compromised, it typically won’t be resolved in a peaceful way.

Over time, it will be clear who holds what power in terms of economics, trade, capital, technology, geopolitical, and military.

The two powers can peacefully evolve if it’s understood who has what relative powers. The weaker power can move into the subordinate position so this position change can occur without a military engagement.

If they refuse to do so, there will be fighting and the weaker power will end up being defeated painfully.

Transitions of power at the global level can occur peacefully, but it’s rare.

In the past 500 years, there have been 16 such occasions where one power came up to challenge a bigger ruling power. In 12 of those times, there was a military engagement. In the other four, great pains were taken to avoid them.

(Source: Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs)

Dealing with conflicts in the international arena

In international relations, there are none of the traditional constraints that come up in domestic conflicts. There are no relevant national laws, no courts or judges, or other formalities that have to be followed in determinations of what’s fair or not.

To an extent, there are these organizations – e.g., the UN, WTO – but in a global conflict between two great powers, they are not more powerful than the individual powers involved.

Each side only cares about whether it wins or loses, not whether it’s playing fairly or unfairly. They need to play the game how it is.

Only the most powerful may impose rules on themselves in terms of how far they’re willing to go.

Winning involves getting what’s most important without losing what’s most important. Wars that cost more in lives and money than the benefits they provide are not smart to engage in.

There are also win-win approaches that can be pursued to produce positive outcomes for each side. Negotiating with consideration to what the other side wants in order to get what you want.

Within the context of the US-China dispute, China places a reunification with Taiwan high up on its list to the point where it’s willing to fight for it militarily. The US would likely value not having a military escalation. Accordingly, one would think the US would be willing to “trade Taiwan” for something else that’s high up on its list.

Peaceful resolutions of disputes are more likely to happen if both sides figure out what they want most through prioritization and relative weightings of those priorities, and negotiate well in order to trade these effectively.

It is easy to go from minor conflicts into major conflicts that are not worth it – namely, they cost more in lives and money than the value gained.

This is because of:

i) the threat of being killed has to be avoided at all costs, so the desire to act first is high

ii) the tit-for-tat escalation process

iii) misunderstandings and miscalculations combined with the need to make decisions quickly

iv) the power that’s declining tends to not want to back down or may bear costs of doing so quietly

The first influence is the classic prisoner’s dilemma. The best option is to cooperate in the ways possible. However, if you’re also dealing with someone who can wipe you out and you’re not certain what they will do, the equilibrium of the game (i.e., the logical thing to do) is to squash the other before they can squash you.

Like in trading, self-preservation is the number one consideration. You don’t know if they’ll wipe you out, but you do know it’s in their interests to do so before you wipe them out.

That’s the basic situation that powers find themselves in. They need to have assurances that they won’t be wiped out to avoid having to go the route of having to kill the other side first.

Wars also commonly occur because of the process of tit-for-tat escalation. This is common in trade conflicts and also in currency devaluation moves.

One side doesn’t want to lose out on what the other side captured in the previous move. So, they respond in-kind to not only avoid losing out but also to avoid being perceived as weak.

These types of escalations must be avoided for peace to ultimately win out.

Misunderstandings and misjudging a situation when things are changing quickly is also a big risk.

Moreover, declining powers tend to want to fight rising powers more than would be logical. Fighting is a natural thing to do when standing down is essentially regarded as a defeat.

Even though the US fighting to defend Taiwan would probably be a bad idea in terms of the lives it would cost and the overall costs relative to the merits – i.e., the US stands a high chance of losing a battle over Taiwan – if the US doesn’t stand to fight, it could lose trust among its allies.

Moreover, leaders often depend on standing strong internationally to help prop up their domestic political support to remain in power.

All of these taken together usually mean that wars often accelerate even though cooperating and competing in peaceful ways are generally the logical thing to do.

Opinions of the population and how leaders lead

Leaders often rile up their populations with emotional appeals and statements that are misleading or outright false. This may help with their support, but it can also increase the odds of wars that are not good choices.

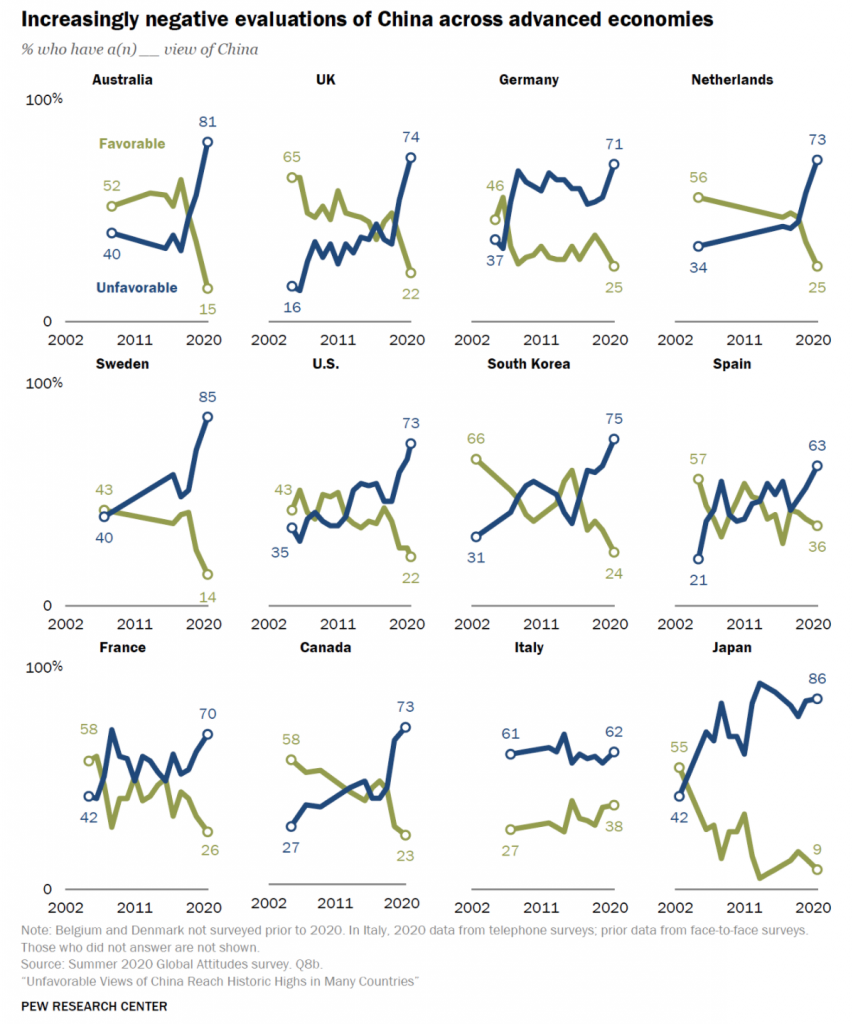

Views toward China are increasingly negative in the Western world.

(Source: Pew Research)

Some of this has to do with China’s increasing aggression in the world and its human rights stances that are controversial internationally.

Surveys of the Chinese public’s opinion of the United States is not widely published; however, some have asserted that it’s likewise worsened.

So, increasingly, there is the sentiment on both sides to accelerate conflicts. In the US, a negative attitude toward China is one of the few things that both the left and right agree on given the wide polarity.

Winning and fighting a military war

Both sides want power and the ability to negotiate from a position of strength.

To do so, the best way is to outcompete the other side in the various ways possible – economics, capital, and technology being the big ones.

Overall, we can acknowledge that the US and China are:

i) In competition on various fronts – e.g., trade, economics, capital, technology, geopolitical, and military superiority.

ii) Each will follow a system and way of operating that they believe works best for what they’re trying to achieve.

iii) The US currently has an advantage on most of these fronts overall and within many sub-categories. But time is not on their side and China is advancing rapidly in a number of them.

Moreover, China has about 4x the population. That also underestimates the Chinese population’s strengths in other ways.

For example, 8x as many Chinese students are going into math, engineering, and other science disciplines as US students.

iv) Even though population matters, it’s not everything. And even smaller countries can become leading global empires if they do certain things well and act well with each other internally.

It’s not so much about sheer numbers as having the right mix of factors.

These includes:

1) Having strong and capable leadership.

2) Strong education, which also teaches values.

3) Strong civility, work ethic, and character (a combination of family and school).

4) Strong rule of law – i.e., respect for rules, low levels of corruption.

5) Having a common purpose – e.g., the “American Dream”.

6) A quality system for allocating resources.

7) Being open to the best thinking possible.

8) Competitiveness in the global markets such that its revenues exceed its expenses.

9) Strong income growth leads to investments to improve infrastructure, education, and R&D.

10) New technologies for commerce and the military.

11) High productivity (output per unit of time worked) to increase overall wealth.

12) High shares of global trade.

13) Strong military.

14) Robust financial center (e.g., Amsterdam in the Netherlands in the 1600s, London in the United Kingdom in the 1700s and 1800s, New York in the 1900s and 2000s, and perhaps Shanghai in China as it develops as the century wears on).

15) Strong currency and strong debt and equity markets

Even though the Dutch and British empires never had large populations, per se, they did score well in virtually all of these markers.

Impact on Markets

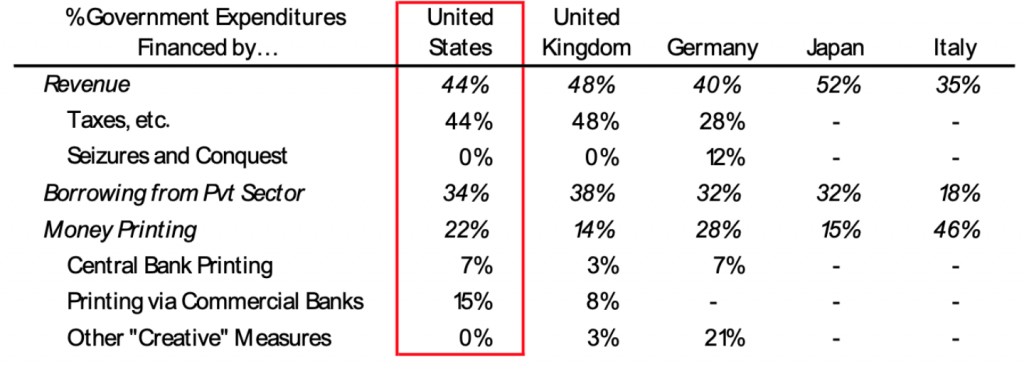

In all major war situations, policymakers react by raising taxes, borrowing, and “printing” money.

For example, below is the breakdown of borrowing during World War II among the US, UK, Germany, Japan, and Italy.

Traditionally, because governments have to:

a) print a lot of money and create debt, and

b) control the interest rate on it to avoiding crushing interest costs…

…this is bad for cash and bad for bonds.

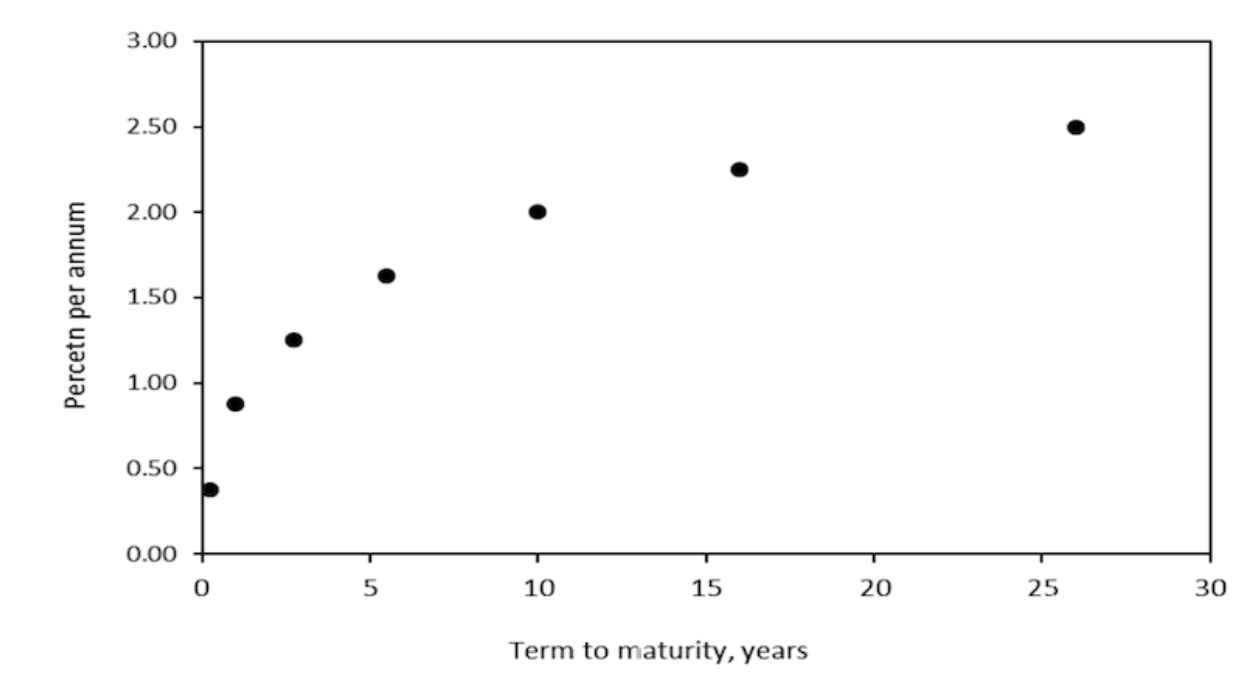

At the same time, the steepness of the yield curve matters.

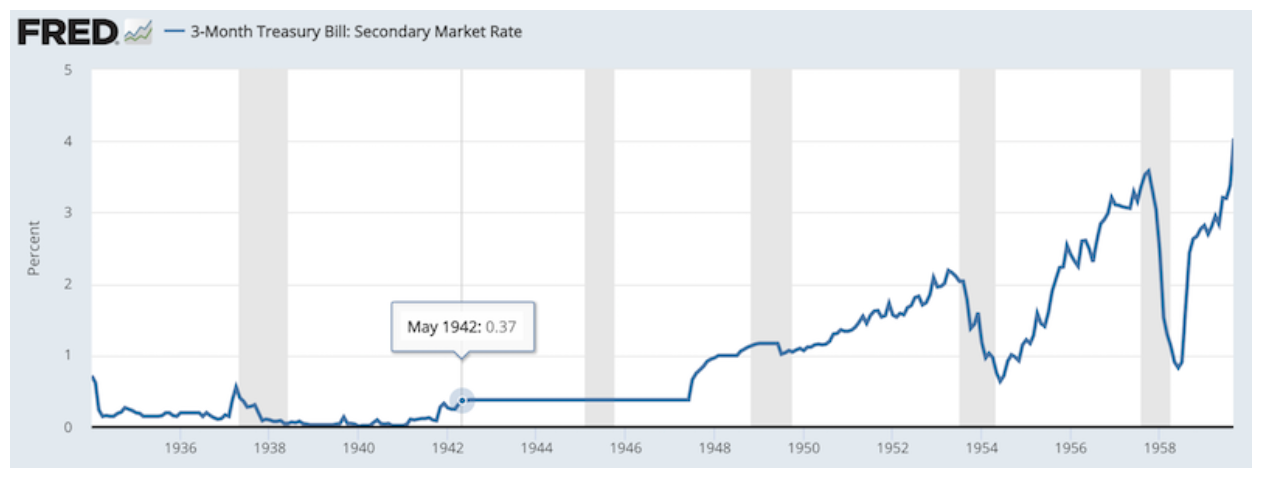

For example, in the United States during the 1942 to 1947 period, interest rates were largely fixed along various parts of the curve as part of its yield curve control program.

(Source: New York Federal Reserve)

From May 1942 to June 1947, short-term interest rates were held at 0.375 percent.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

With the steepness of the yield curve, one could still borrow cash and invest at longer term rates and capture a spread of about two percent.

Given rates were fixed to stay low, there was virtually no downside so long as the government kept its promise to borrow at that rate. Given this incentive, the private sector could fund a portion of the war. In the case of the US, about one-third of the overall spending, with the other two a mix of taxes and money printing.