The Geopolitical War: Impact on Markets & US-China Relations

The geopolitical war occurring between the US and China is one of the many conflicts occurring between the two countries, including:

i) trade and economic

ii) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military

As we’ve mentioned in other articles, understanding these various conflicts are important for traders and investors to understand. They involve the two largest economies and the countries with the two largest stock and bond markets.

How they will play out will influence capital flows and how the overall world order is set.

Typical cycles of empires

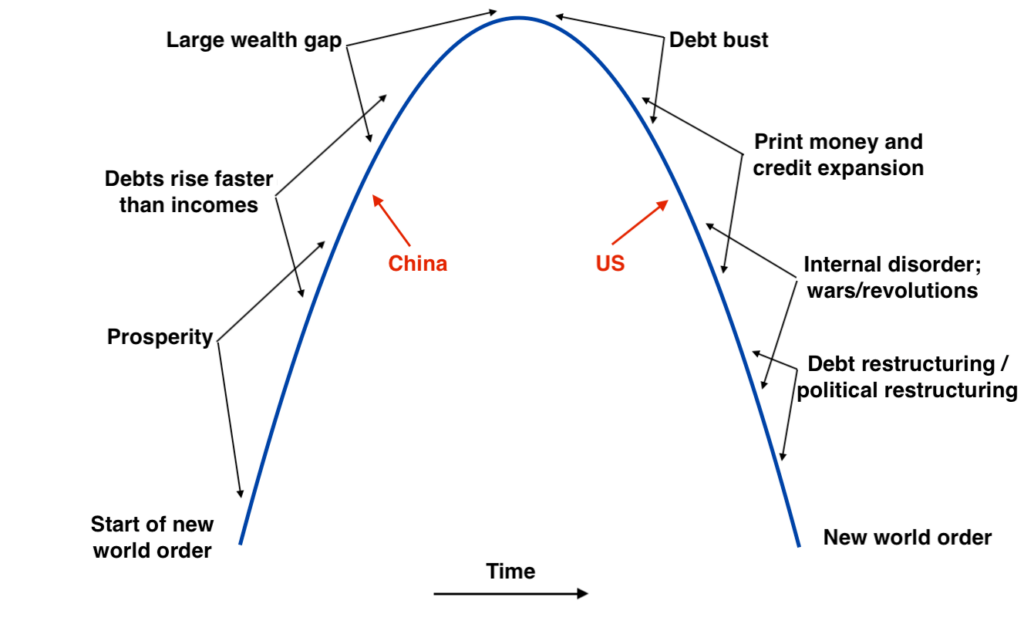

Knowing the typical cycles of empires and knowing the cause-effect linkages that drive them can help anticipate a range of future possibilities. By studying what happened in other empires and in other lifetimes we can better understand what drives outcomes and the markers of where we are relative to what’s likely to take place going forward.

The development arcs of empires roughly follows the template at the bottom of this section. It starts when a new order or system is established after a debt and political restructuring. This often occurs after wars or revolutions take place.

There’s generally a period of prosperity or rebuilding that follows and living standards rise. Eventually, as people spend more than they produce and the debt-financed purchases don’t pay for themselves and debts climb relative to incomes.

As the cycle goes on, there’s a larger wealth gap and eventually a debt bust when there’s not enough income, new borrowing, and sales of liquid assets to service the debt. To fill in the gap, there’s money creation and a new expansion of credit by the central bank.

“Printing” money is necessary to get out of a crisis. But it causes a lot of that money to go into financial assets. Those who are well-off own assets, those who aren’t largely don’t own them. This larger wealth gap increases class resentment and social frictions.

Often there are other problems producing economic, social, and political division as well. For example, in the United State, offshoring jobs to China (where it’s more cost-effective to produce) has hollowed out a lot of local rural economies and left people behind. That’s caused problems like higher opioid and drug use and lower lifespans in the bottom economic quintiles.

You see this friction in the rural/urban split politically in the US. This causes you to get more populism of the left (e.g., Sanders) and populism of the right (e.g., Trump), larger overall political gaps, and more dysfunction.

This is also self-reinforcing. When the “extremists” outnumber the moderates in both parties there’s a self-perpetuating pull toward greater conflict and polarity.

The parties tend to be pulled to greater extremes because if individual politicians don’t move in that direction they could be defeated in primary elections by greater extremists. An example of this dynamic is New York Senator Chuck Schumer where there’s the possibility that he could be unseated by a Democrat who is more left-leaning than he is.

We believe the China and US are approximately where they are in their arcs as pointed out on the following graph.

China is ascending in global power while the US is going into the classic period where there is more internal disorder and conflict as people fight over wealth, political power, and ideology.

Revolutions can be peaceful or they can be violent. Internal fighting sometimes goes hand in hand with external fighting due to conflict with foreign powers. After the fighting is over and winners are determined, there’s a debt and political restructuring and the establishment of a new world order.

Sovereignty and governance

Sovereignty and maintaining the integrity of its top-down governance structure is a particularly important issue to China and is a big part of the geopolitical war impacting US-China relations.

The matters of sovereignty and governance are two things that China will not compromise. The US must be careful in dealing with these issues because they are matters that China will quite likely be willing to “fight to the death” over.

Matters related to economics, trade, capital, and technology are things that China is likely work to influence in a non-violent way.

As a result, the geopolitical war and the dual elements of national sovereignty and its government (i.e., the Chinese Communist Party) are two things that the US must be careful in contesting to avoid having the conflict boil over into something violent.

China considers what it does on the mainland, and with respect to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the South and East China Seas to be a matter of its own sovereignty.

China has a much longer history than the US and Chinese policymakers study it more and have longer time horizons than US policymakers. So they tend to draw on past experiences to inform current ones in determining where they’re going and what they need.

During parts of China’s history, it was subject to foreign invasions.

So, as you might imagine, during China’s internal conflict in the mid-1940s that led way to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao Zedong and his successors place great emphasis on sovereignty.

The place critical importance on not only complete sovereignty within their own borders, but to get back parts of China that were previously taken from them, notably Hong Kong and Taiwan. Moreover, that also means not being so weak that they can be intimidated and pushed around by foreign powers.

China’s importance placed on sovereignty and its own top-down culture that drives the way it operates means the Chinese will not accept US demands to change how China runs things internally.

For example, the US wants China to be more democratic in its political institutions, change their policies toward Hong Kong and Taiwan, treat Uighurs and Tibetans differently, among other things.

Even though the US is “stronger” overall at this point in time, China won’t accede to US demands on matters of internal policy any more than the US would acquiesce to China’s demands on what the US should do within its own borders.

Moreover, China largely believes the Western world is too prone to proselytizing its beliefs about how the rest of the world should operate by imposing their values, ethics, morals, and beliefs on others.

The Chinese believe this has been going on for roughly a thousand years, essentially ever since the Crusades. They believe that the inclination to proselytize and undermine China’s sovereignty prevents it from being all China can be based on the approaches that they feel are best for their culture and the way they want what’s best for the country.

Some within Chinese leadership believe that the US would willingly topple the Chinese government if they could, which they find intolerable.

Many recognize that the US often proposes regime change as part of its way of managing the global order.

The issue of Taiwan

Taiwan and issues concerning its sovereignty is a dangerous potential point of conflict between the US and China. It’s a thorny matter that the two sides will have great difficulty resolving in a peaceful way.

The Chinese generally assign low odds to the US working to unify China and Taiwan unless coerced to do so or assent when China is stronger.

The US sells defense systems and military equipment to Taiwan, so it’s difficult to imagine a peaceful unification process.

Therefore, to get Taiwan back, China will need to build power, militarily and elsewhere. And they are likely to build their military capabilities at a faster clip.

It’s not certain how a sovereignty issue over Taiwan would play out. It’s not known if the US would use its military to defend Taiwan. Not doing so would be a big geopolitical win for China and could set a bad precedent for the US.

If the US doesn’t fight over Taiwan to avoid escalating the conflict, where would the US draw the line when it might come to other territories and other matters related to the Pacific?

Since World War II, the US has had large control over the Pacific. Failure to do anything with respect to a Taiwan conflict would effectively mean the decline of the US empire in the Pacific.

The British loss of the Suez Canal in 1956-57 was symbolic of its decline as an empire given the Canal’s importance in helping them transport goods to India and expand its interests in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The implications went well beyond only that. It also meant the end of the British pound as a top reserve currency. While the British pound is still around five percent of global reserves today, that’s a sharp drop from when it was the world’s most used currency.

The US retreating from Taiwan or losing a battle over the territory would be humiliating for the US considering its declaration to defend it. The stronger China gets the more it’ll want to uphold its “One China” policy.

If the US were to fight, any battle that costs US lives would be likely to be unpopular in the US, and it would also be a struggle for the US. The main question is whether a prospective conflict over Taiwan would lead to a broader war.

That should give pause for everyone, as any broader military engagement that comes out of it would be highly destructive for both sides. The fear of it alone should make everyone want to do everything in their power to avoid that outcome.

China’s influence globally

Unlike imperial expansion, where countries try to maximize their reach globally through land and control of foreign countries, China is unlikely to try to forcibly influence other countries.

As mentioned earlier, Chinese leadership tends to have great historical perspectives and will draw on past history to inform the present. Military wars are terribly costly. Starting them and losing them is practically the worst decision a leader can make.

Sometimes great global conflicts start as small skirmishes and erupt into larger ones. World War I was a prominent example.

If a cooperative relationship was possible where the world can be divided into spheres of influence, this is better than a war where mutual destruction is possible.

At the same time, each country has limits on what they’re willing to compromise and what they’ll fight for militarily if they have to.

For that reason, from a practical perspective, there will be more challenging times going forward and China will place great emphasis on the defense of national sovereignty and security, and some matters represent so-called red lines (like Taiwan).

Countries generally emphasize lands, countries, and areas of influence that are closest to them and the parts of the world necessary for getting them what they most need (i.e., not being cut off from essential technologies or essential commodities).

They also care about the markets they export to, just to a lesser extent.

Both China and the US have areas they view as the most important to them.

China puts the most priority on areas that they consider to be a part of China.

Secondary importance is placed on structures they border, like the East and South China Seas, and the lands they’ve invested in (e.g., countries involved in the Belt and Road initiative). This also includes parts of the world they rely on for critical imports.

Tertiary importance is placed on countries they are allied with or have an economic or strategic interest in.

In the latter half of the 2010s China materially expanded its activities in these areas.

The Belt Road initiative, since being adopted in 2013 as part of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, is a part of around 70 countries and focuses on infrastructure development and forging relationships in mostly resource-rich developing countries. It can be thought of as a type of 21st century “Silk Road”.

It includes various types of economic and investment activities – for example, loans, building of roads, military support, and financial asset purchases.

At the same time, the US is withdrawing from these areas.

Some countries will even have to think about whether they’ll allow China to buy assets within their borders if there are strategic reasons to limit a foreign power’s ownership of them.

These initiatives are having more influence on geopolitical relations. For example, more countries are having to think about whether they’re more aligned with China or the US economically and more aligned with China or the US militarily.

Those in closest proximity to each country will need to think most closely about these questions.

Most countries globally would probably assert that they’re more aligned with China economically because of trade and capital flow considerations.

On the military front, most would argue they’re still aligned with the US. However, when it comes to Asian-Pacific affairs, is the US still more powerful? Would the US fight to protect an ally and would it win?

China’s strategic investments through the Belt and Road initiative, and the financial and economic help that provides, is similar to the support the US provides to its allies. (Many of these relationships started after World War II.) It helps to secure better relations.

The US’s influence relative to China’s is declining. Not that long ago, the United States had no major rivals, so the US had a lot of power to influence other countries in a more unipolar world.

From the 1945-1990 period, the US’s biggest rival was the Soviet Union and its allies, along with some other developing countries that weren’t threats economically. However, outside of nuclear power, the Soviet Union wasn’t a big threat because of its economic inefficiency.

China’s influence over and within other countries is growing while the US’s is diminishing.

We can also see this within the various international organizations, such as the IMF, World Bank, WTO, WHO, ICJ, and the UN.

Most of these were set up after World War II by the United States given the new global order that was established. For example, IMF and World Bank headquarters are in Washington DC and the UN’s headquarters are in New York because of this.

The US has lessened its ties with these organizations in recent years and China has taken a bigger role in them as its power expands.

Decoupling and alignment

Going forward, both countries will decouple from one another in various ways – e.g., trade, economics, technology, spheres of influence.

This will be essential given the circumstances, but will result in reduced efficiency in various ways. It will impact certain things differently than others.

Countries will increasingly feel inclined to align with one or the other and alliances will develop. Economics and military will be important, but how China and US handle their power will also be influential as well.

Different countries, as a result of their cultures, have different values. For example, we might expect to see most of democratic Europe more closely aligned with the US while the more autocratically-run Russia is likely to side with China.

Xi Jinping is largely viewed as a heavily autocratic figure, given his consolidation of power within the Chinese Communist Party and his ability to potentially rule without being impacted by term limits.

The US’s executive leadership is also in flux and turns over every 4-8 years, usually between opposing parties. (The last time a party won three consecutive presidential terms in the US was in 1988.)

Because of the US’s wealth, values, and ideological gaps, that flows into political outcomes. There’s more populism of the left (e.g., the popularity of Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) and populism of the right (e.g., Donald Trump).

The US elected Joe Biden to begin serving in January 2021. That may potentially represent a shift where there’s a desire to go from an anti-establishment, populist candidate to a more establishment, moderate candidate.

But it’s too soon to tell if Biden’s election is demonstrative of anything, as the presidency is simply a single data point taken once every four years.

Populists are still popular based on polling and voting results, which reflects a country that’s heavily divided economically, socially, and politically.

So while the world pretty much knows what it’s getting with China’s leadership, little is really known how US leadership will evolve over the next 10+ years and how skillful and/or fragmented it will be.

Some will argue that China is more predictable. Leadership changes infrequently and the one-party rule means most everyone is rowing in the same direction. They have their disagreements, but privately.

US leadership has the turnover and the composition of Congress changes to varying extents every two years. There is a lot of division between the two main parties and also within them.

Even thin margins make a lot of difference due to the polarity. Many votes are along party lines.

The alliances that form will be important. Historically, stronger countries are eventually disrupted by an alliance of countries who may be weaker individually but stronger collectively.

China and Russia is an important relationship for traders and investors to watch. Two out of three can work to overpower or at least neutralize the third.

China and Russia is a natural alliance, with similar styles of governance, they share a border, and each has plenty of what the other needs.

Russia has natural resources and military defense systems to give to China, while China has monetary resources to help Russia develop. They are natural military allies.

How different countries align on the issues will be important to watch.

For example, if a country is welcoming of Huawei, that may hint it probably sides more with China than the United States.

Domestic conflicts within the geopolitical war

The geopolitical war brings many types of different political risks at the international level.

But in both countries, there are different factions and ideological groups wanting to fight for control of governments.

Any changes in leadership, in the various ways possible, may cause policies to change in ways that are difficult or even impossible to predict.

However, the forces governing the cycle are still the forces, and those are things that leaders in both countries will have to face.

For example, China’s leadership will have various challenges to consider economically in terms of:

i) Continuing to restructure their economy (from the old industrial sectors to services and digital technologies).

ii) Restructuring their capital markets. Ensuring they have ample liquidity will give foreign investors confidence that that main risk is under control.

iii) Restructuring their debt, which is growing too high relative to incomes. This means refinancing existing debt and gradually ease fiscal and monetary policy to avoid the debt-related contractions that often put economies back a decade or more.

iv) Manage their capital account. Give stability to the renminbi to bring along its status as a global reserve currency and help push capital toward productive domestic consumption and investment outlets

All leaders and all individuals within the cycles (including us) will experience a certain set of situations as part of our lives based on where we come in and where we leave off.

Many people throughout history have experienced these cycles in many of the same ways. So we can study what they were faced and how they handled them to better understand where we are in the analogous stages. Accordingly, we can roughly try to envision the span and assortment of possibilities and the potential outcomes.

Market impacts of the US-China geopolitical war

Typically, in the part of the cycle where the US is now, it is not good for cash and bonds. This is because they’re printing money and creating a lot of debt, and it doesn’t yield anything. People want alternatives.

It’s a better environment for certain types of stocks that are better stores of wealth. It also tends to be good for gold (a type of alternative currency) and good for commodities.

And because the relative economic weights of different countries are changing (notably, the US weight is going down while China’s is going up), it makes more sense to diversify between countries and currencies.

On the FX front, the main reserve currencies are too strong relative to their fundamentals (e.g., USD, EUR, JPY, GBP). CNY looks attractive relative to its fundamentals, given China’s share of global trade and its growing economic weight.

More investors, sovereign wealth funds, and central banks are likely to diversify into the renminbi over time and decrease their allocations toward the others. Gold is also likely to go up.

This also puts Japan and the western world in a difficult spot when they are expanding their deficits at a time when its debt is becoming increasingly unattractive. This puts more of the burden on their central banks to buy it, devaluing their currencies in the process.