The Capital War’s Impact on Markets & Role in US-China Relations

US-China relations, and the capital war conflict within it, is and will be a big driver of markets going forward and is important to understand even for those with shorter-term trading orientations.

The same things tend to happen over and over again for the same reasons historically. By studying what happened in other societies and other empires in other lifetimes we can better understand what drives outcomes and the markers of where we are relative to what’s likely to transpire.

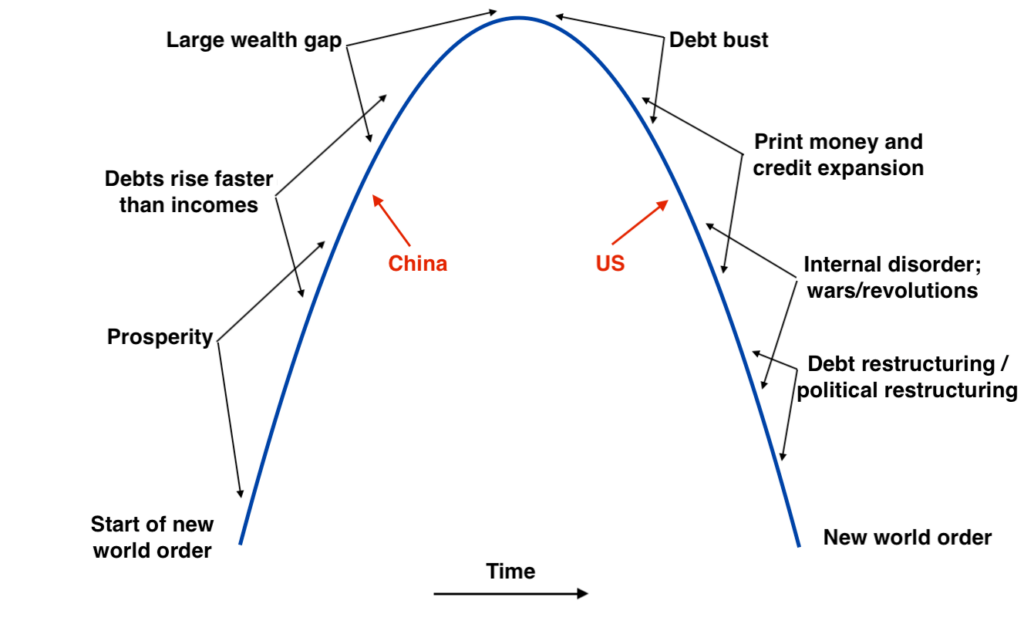

In terms of a generalized framework, we believe the development arcs of empires roughly follow this template and believe the China and US are where they are as pointed out on the following graph.

As traders and investors, we have to anticipate what’s likely to happen and place money on these bets. In turn, we get rewarded or penalized on these trades in real-time.

The capital war is among the five categorical types of conflicts that countries go through, including:

i) trade and economic

ii) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military

The main risks

China and the US both have risks associated with the capital war, but they’re unique from each other.

China’s main risk is being cut off from capital by developed market economies, especially from dollar funding by the US government. The US can also unilaterally choose to cut off its debt payments to China if relations were to deteriorate enough.

The main risk for the United States is the loss of its reserve currency status. The US is more than 50 percent of all global reserves (including gold in the tally) despite being only about 20 percent of all global activity.

The renminbi is only a minor player internationally so far. But it’s expected to increase over time given it’s the second-largest economy, and has the second-largest stock and bond markets globally.

Capital war tactics commonly follow three main themes:

i) Financial asset freezing or seizure

ii) Blocking financial access

iii) Embargoes of key trade items

Today’s term is “sanctions”; all of these three are possible.

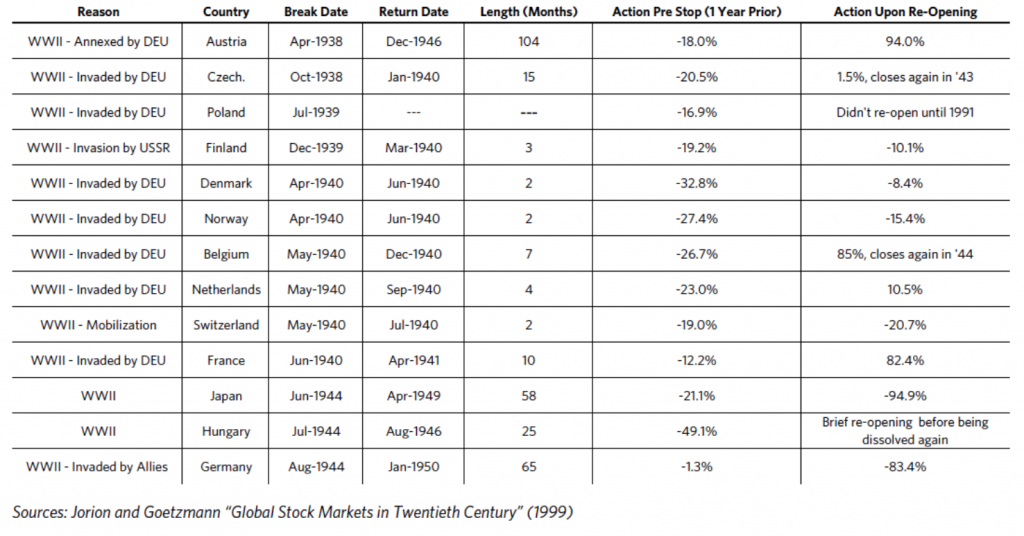

Multiple countries closed their capital markets during World War II.

The goal of a capital war is to restrict what the opposition can do. No money means no power.

Sanctions can take many different forms. There are economic, financial, diplomatic, and military sanctions.

There are also many sub-categories within them and ways to apply them.

At the start of 2020, there were nearly 10,000 US sanctions in place that were targeted at governments, companies, and individuals.

The US has the biggest lever over international sanctions because it has the world’s top reserve currency (people all over the world want to transact in it and use it as a store of value) and the largest influence over the global financial system.

That enables the US to prevent most entities from receiving capital by preventing financial institutions from doing business with them. Still, many sanctioned entities are highly creditworthy and banks would want to traditionally do business with them.

For the government to enforce sanctions, they can threaten these financial institutions from being cut off from the global financial markets if they choose to do so.

For the US, sanctions generally work pretty well, which is why they are so pervasive.

And because they are generally so effective countries naturally want to develop ways to get around them if they are harmed by them.

So, they have two main options:

a) develop an alternative payments system

b) weaken the US’s power to apply them

China and Russia, as examples, are both encountering these sanctions and are also at risk of confronting more of them. As a result, they are motivated to develop an alternative payment system.

Central banks will want to have a digital currency. This will make it easier to use and is similar to the concept of a cryptocurrency, but of course centralized under the purview of a government.

China will want to bring along its currency as more of a broadly accepted reserve asset globally. Naturally, that will come at the expense of the dollar and is a big part of the capital war that will go on. It will be part of the decoupling phase that both countries will go through.

The US dollar’s role

A big portion of the US’s power comes from its ability to print the world’s money from having the world’s top reserve currency and the operational powers that come with that, such as control over the clearing system.

US finances are well past the point where all the money due will be paid with productivity gains or spending cuts, so the US is at risk of losing some of this power. The Chinese are positioning themselves to gain power over time.

US dollar holdings in foreigners’ portfolios (e.g., most importantly within portfolios controlled by governments, including the reserves of central banks and sovereign wealth funds) are too high in relation to what they ideally should be.

These include various long-run measures:

i) The size of the US economy relative to the world economy

ii) The size of the US debt markets’ capitalization relative to the capitalization of other markets

iii) The asset allocation that foreign investors would hold in other to balance their portfolios in a prudent way

iv) The reserve currency holdings that would be suitable to meet the needs of trade and capital flow funding

USD-denominated debt is large in relation to all these measures as reserve currency status falls with a lag relative to the overall empire’s decline (typically, but not always, a better system is devised first).

The dollar is perceived as a safer asset than is justified and USD borrowings are disproportionately large.

Currently, reserve managers, central banks, and others who are responsible for determining what share of their holdings should be in what markets and what currencies are not going to be inclined to increase their share of USD reserves in line with the larger amounts of US bonds that need to be sold.

In fact, many are considering reducing their exposure to US debt outright. If this happens, it will require more purchases of this debt by the US central bank, the Federal Reserve.

The US government is increasing USD-denominated debt at an extremely fast rate. The amounts that need to be produced are not likely to see adequate demand. The Fed will have to buy it as part of its monetary policy obligations and effectively “monetize” it.

Moreover, the financial incentives to hold this debt are low because the nominal yield on it is zero or negligible and there’s a negative real yield.

On top of that, holding debt as a store of value or means of exchange when you have conflict with the creditor is not as desirable as it is when relations are better.

China holds less than five percent of all US Treasury debt, but is certainly a risk.

Other countries know that the same actions taken toward China and their holdings of dollar assets could also be taken toward them. So, the perceived risks of holding dollar assets are higher, which can reduce the demand for them.

It’s also important to note that the USD’s role as the world’s leading reserve currency relies on its ability to be exchanged freely between countries and also work well for most countries as a means of exchange and store of value.

Therefore, the extent to which the US subjects the dollar to controls on the way it can flow, or runs monetary policy in ways that are in conflict with the world’s interests relative to its own interests, the less desirable the dollar will be.

The general idea is that a lot of elements are stacking up that are against the long-term value of the dollar.

But at the same time, the dollar is so widely used that it’s more valuable and difficult to replace.

Dollar weakness is likely to transpire over a longer period of time.

Testing the limits

The US is testing the limits of far they can push the dollar with the following ongoing mix:

i) the dollar being weaponized to help the US get what it wants

ii) producing an enormous amount of dollar-denominated money and debt

iii) fueling its debt binge through negative (and falling) real returns on the debt, and

iv) having a fiat-based monetary system where the value of the money is based on government authority alone

We don’t what the limit to this is and we won’t know until it can’t go on further. By the time we know, we’re already past the point of no return.

The supply of new debt being pushed out by the US is too high relative to its demand. That means the Fed has to buy it and effectively monetize it. That devalues the currency.

The pressure will either come on the interest rate side (i.e., higher interest rates) or through the currency (down). The Fed won’t want interest rates to climb because keeping nominal interest rates below nominal growth rates keeps the spread necessary to keep the economy going.

So, in a “free market” all the debt creation might signal a bad environment for bonds. But if the central bank wants or needs to buy it all, they’ll prefer to devalue the currency instead. It’s more discreet and more politically palatable.

The US government, through its deficits, and the Federal Reserve are basically running a big experiment to see how much money and credit can be produced through the dollar’s reserve status without fracturing it.

Though the US has the clear edge in the capital war currently as it pertains to its multi-conflict front with China, it’s clearly in very risky territory given the supplies of dollar-denominated money and debt currently being supplied and the limited relative demand for it.

However, this doesn’t mean that anyone can be confident of the near- and medium-term trajectory of the dollar (i.e., as in losing value) or its value as a reserve currency.

Negative nominal and real interest rates

Negative nominal and real interest rates in very large debt markets were previously seen as very unlikely – that is, assuming governments aren’t forcing controls on these markets to get those conditions.

Usually these circumstances might only occur in one of two scenarios:

i) Capital control situations where there are large budget deficits and monetizations of debts to accommodate massive spending. These are generally war years when government capital controls are required and interest rates are directly targeted to control interest-related costs. This is commonly known today as yield curve targeting (YCC).

ii) Under the most depressive and deflationary economic conditions when there was a flight to safety to be defensive.

Looking through history you would have seen that these things have never happened before.

This generally doesn’t occur because it’s difficult to understand why the holders and buyers of said debt would want to keep holding it rather than move their wealth into other assets.

It gets down to who bought the debt and for what reasons.

In this case, it is not private sector or foreign demand but rather their own central bank. This is true throughout the US, developed Europe, and Japan, essentially all the main reserve currencies.

So, essentially policymakers have a trade-off between higher interest rates or devaluing the currency. They will choose a lower currency to keep the economy and financial system going. But it’s still a trade-off, not a free lunch.

As a trader or investor, you will have to think about that trade-off and what it might mean for portfolio construction.

- For example, how much of your portfolio do you want in dollars versus other currencies?

- How much do you want in dollar-denominated bonds?

- How do you effectively diversify your currency exposure? (For example, having perhaps ten percent of a portfolio in gold can be a good starting point.)

While the US is testing the limits of how much it can get out of the dollar, no one can be confident that the dollar will severely devalue or lose its reserve status in the near-term.

What loss of USD reserve status might look like

While we don’t know when the dollar will diminish significantly as a reserve asset, we can recognize what it will look like and there won’t be much policymakers can do to stop it.

It will involve the following:

i) People wanting to sell USD-denominated debt and move their wealth elsewhere.

ii) People wanting to borrow in dollars to take advantage of the cheap funding to make higher returns with it.

This will put the Fed in a bad position. It will either need to:

a) allow interest rates to rise to unacceptably high levels to defend the currency (i.e., compensate investors enough for holding it), or

b) print money to buy Treasury debt, which further reduces the value of money (the dollar) and debt denominated in the currency

When faced with this choice, central banks almost always choose choice B in printing money, buying the debt, and devaluing the currency.

This process typically continues in a self-reinforcing way because the interest rates being received on the money and debt are not sufficient to incentivize investors to compensate them for the depreciating value of the currency.

This process will go on to a point where the currency and real interest rates establish a new equilibrium balance of payments.

In plain terms, this means there will be enough forced selling of financial assets, goods, and services and enough reduced buying of them by US entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

How can the US lose its reserve status without good alternatives?

Are there no good alternatives to challenge US reserve status?

Right now, global reserves – i.e., share of central bank reserves by currency – look like this:

– USD: 53%

– EUR: 20%

– Gold: 14%

– JPY: 6%

– GBP: 5%

– CNY: 2%

Their relative weightings are due to a combination of a) the fundamentals that influence their relative appeals and b) the historical reasons.

The USD, for example, is as high as it is because of the US’s reputation and less so its fundamentals.

Reserve status lags fundamental reasons by a long time because it’s not easy to change the system. This is similar to languages. They last because people a lot of people are accustomed to using them.

The current four top reserve currencies – USD, EUR, JPY, and GBP – are in place because they represented the leading empires following the post-World War II period even though on a fundamental level they are not that attractive.

The levels of each currency are out of whack relative to what proportions you’d want to have to be balanced (in the various ways discussed above) and where the world is going.

The dollar, European currency, yen, and pound are in wide use because they came from the old Group of Five (G5) to represent the top five countries by per capita GDP in the 1970s (US, West Germany, France, Japan, UK), but that is now outdated.

Fundamentals of each of the main reserve currencies

We’ll briefly discuss the fundamentals of each of these main reserve currencies, including gold, which is a reserve asset that acts more like a currency than a commodity.

US dollar

The US dollar has already been covered, but suffice to say its relative proportion of global reserves will need to come down over time.

Euro

The euro is essentially a pegged currency union that’s weakly structured by unifying many different countries’ monetary policies that have quite different economic conditions. European countries are highly fragmented on a number of different issues and the region is weak both economically and militarily.

Gold

Gold is a popular reserve asset because of its track record going back thousands of years. Because it has worked for such a long time it is valued accordingly.

Prior to 1971, during the Bretton-Woods monetary system (and in many other societies and empires before then), gold was the foundation on which money was based on.

It is a non-credit dependent asset so it bears no risk from being excessively “printed” unlike fiat currencies.

The gold market is limited in size and relatively illiquid, so its use as a reserve asset is limited in accordance with that.

Yen

The yen suffers from many of the same financial issues that are plaguing the US dollar, including a lot of debt that is growing quickly and being purchased by its domestic central bank such that it’s paying very low nominal and real interest rates.

But Japan is not a leading economic and military power, currently standing at around five percent of global GDP, and losing share as time goes on. The yen is not widely used or valued outside Japan.

British pound

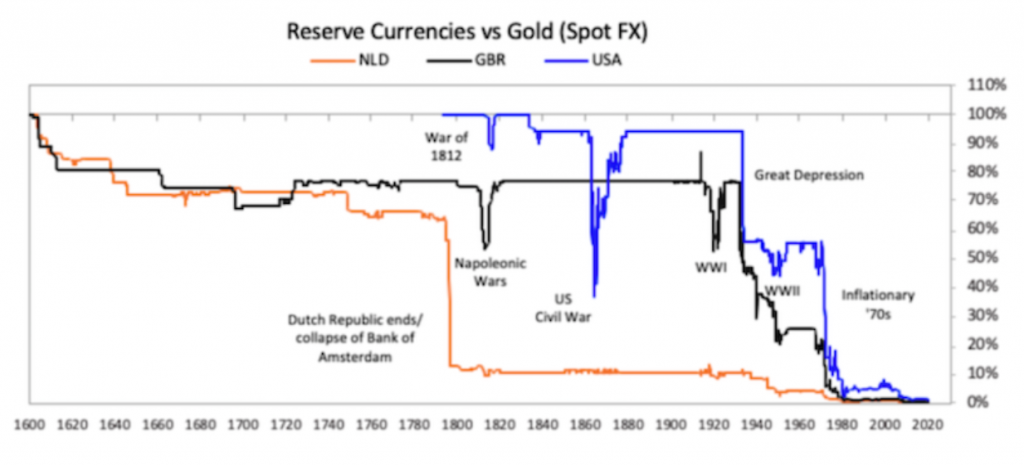

Before the US dollar became the world’s reserve currency, there was the British empire, which overtook the Dutch empire’s relative power somewhere around the mid-18th century.

The UK is about only three percent of global GDP and has twin deficits (fiscal and current account) and has relatively weak overall geopolitical power.

Its proportion of global reserves is another anachronism of the way reserve status works long after the decline of an empire’s influence.

Chinese renminbi/yuan (RMB or CNY)

The Chinese renminbi/yuan is the only main reserve currency that makes sense on the basis of its fundamentals.

China has the largest share of global trade of any economy.

Its economy is the second-largest and is projected to be the largest within the first half of the 21st century. It is already richer than the United States on an asset and liability basis.

The RMB has been managed to be approximately stable versus other currencies and on a purchase price parity (PPP) basis. Its foreign reserves are also large.

On top of that, unlike the other reserves, it doesn’t have a zero percent interest rate or negative real interest rate.

China does have a debt problem, but it’s denominated in local currency where that can be controlled. They will need to restructure it over time.

China also doesn’t have the problems associated with the monetization of debt that the other countries do.

The main drawbacks to the RMB are the following:

– it’s not pervasively used globally

– China doesn’t have widespread trust of global investors, especially with its unique form of governance (“state capitalism”) relative to the West

– its capital markets are not yet as well developed and Shanghai and Shenzhen are not considered global financial centers

– its payments clearing system is not developed

What happens when currencies are devalued

When currencies lose their relative to appeal, the currency sells off and is devalued, with the capital finding new homes.

Capital finds its way into other investments, such as precious metals, commodities, various types of real estate, stocks, and so on.

It’s also very important to note that the US could lose its reserve status even in the absence of “something better”. That is, there is no strict need to have an attractive alternative foreign currency for this devaluation to occur.

Gold, silver, and other commodities are non-fiat stores of value. They are priced as a certain amount of money (in whatever currency) for a given commodity.

If the value of money goes down, gold (for example) goes up in money terms to reflect the devaluation. It’s not that gold’s utility is going higher, it’s just the value of money is going down in gold terms.

The same is true with stocks. Currency devaluations are a good way to stimulate the stock market. Money’s value goes down in stock terms and stocks go up in money terms.

This, however, breaks down in circumstances of hyperinflation.

In times of runaway inflation, there’s a growing divergence between share prices and the exchange rate.

Even though shares will continue to rise in local currency terms, they begin to lag and lose money in real terms in an increasing way.

Gold becomes a popular asset to own, bonds are rendered valueless, and stocks become a terrible investment.

In such hyperinflationary environments, you want to get your money out of the country any way possible. If that fails, people want to buy any asset that’s of a non-financial or “real” character.

The importance of currency diversification

All of the factors discussed in this article is why portfolio diversification is critical, among not just different asset classes but also different geographies and currencies. Capital isn’t so much destroyed as it just moves around.

People in the US, for example, put a lot of trust in their currency because currency problems haven’t been experienced in their own lifetimes.

Most US-based investors do not diversify much by currency. They tend to own a lot of stocks and bonds denominated in their own currency; even most emerging market investments are put back into USD.

This is the natural bias. And it’s easy to understand why the general inclination is to just buy stocks in local currency and have that be the general portfolio.

Those in emerging markets – and particularly those in countries where there’s been a history of debt and currency problems (e.g., Argentina, Turkey, Russia) – tend to place less faith in their currencies and many choose to diversify by owning a larger proportion of foreign assets and/or alternative stores of value like gold.

China’s capital market development

China’s currency and capital markets are likely to develop quickly and increasingly compete with the US’s markets for capital, assuming the US doesn’t interfere with their progress as part of the capital war between the two.

In the years ahead, China’s markets are likely to be much bigger, more developed, and essentially come to rival the US markets in various ways.

This development of capital markets was true for the Dutch Empire in the 1600s, the British Empire in the 1700s and 1800s, and the US empire in the 1900s.

China, of course, must run effective policies that help generate broad-based productivity gains to increasingly make this happen. The Soviet Union, for example, never became a great power during the 20th century (despite its nuclear strength) because resources were not efficiently allocated.

Overall, there is plenty of potential for China to develop its currency, equity, and debt markets given its underinvestment globally in relation to its fundamentals in various ways (e.g., its percentage of global trade, contribution to global growth, size of its economy relative to the rest of the world).

China’s current state of underinvestment

China is close to 20 percent of global GDP and growing faster than the US.

Its global equity market capitalization is around 15 percent, but with about only a five percent weight in MSCI equity indexes.

It’s also heavily underweighted by foreign investors, at just 2-3 percent of assets currently in portfolios.

The US accounts for around 20 percent of global GDP, but accounts for half of all the weight in MSCI equity indexes and almost half of that money in non-US entities.

The general idea is that investment is lagging behind the development, especially for offshore investors.

Building a financial center

The development of the Dutch, British, and US empire coincided with the development of the world’s top capital markets. Each had a leading financial center.

The development of Amsterdam, London, and New York as capital market centers was key to each empire’s development to become the world’s dominant power.

The development of a financial center also typically lags a country’s overall fundamentals. This was true for Amsterdam, London, and New York in the same way the development of Shanghai (and secondarily Hong Kong and Shenzhen) has lagged in its development.

The threat of the development of China’s capital markets to the US

China’s development of its currency and debt and equity markets would be harmful for the United States and its relative power and a big positive for China.

US actions against China in the capital war

US policymakers have a choice to face in terms of whether:

a) they want to disrupt China’s path to developing more robust capital markets through a more aggressive capital war, or

b) accepting that China’s capital market development will eventually enable China to become more self-reliant and less susceptible to being squeezed by US sanctions and other actions against China in this realm.

China’s capital market development will essentially come at the expense of US leadership in this domain.

The US will try to prevent Americans from investing in China’s markets and will move to delist many Chinese stocks (ADRs) from US exchanges.

There are trade-offs associated with doing this.

While it would be somewhat harmful to China’s markets and the companies listed on US exchanges, it will also hurt the competitiveness of US investors and US stock exchanges.

Many US investors won’t have access to China’s market and will aid in the development of exchanges elsewhere.

For example, many Chinese companies are listing on the Shanghai and Hong Kong exchanges and skipping a New York listing.

For traders and investors, that means either buying them on those Chinese exchanges or missing out on them, given they’re listed there and not on ones that most have access to.

Final Thoughts

Generally speaking, there are three things China fears:

1) US military power

2) the US dollar

3) US semiconductors

In this article, we covered the second point, covering the dollar, the rise of the renminbi and its capital markets, and the overall capital war.

China is attempting to bring along its currency to reduce the strength over the US dollar over time.

This will come over the next 5-10 years as it develops its debt and equity markets and brings along its financial center. In terms of more pinpointed actions, China carries out RMB currency swaps with 20-30 countries around the world where its currency is the primary medium of trade with those countries.

Its restraints include, for example, its reluctance to liberalize its capital account and to liberalize its exchange rate with other countries.

This will come along over time, as free-floating its currency too soon essentially places its politics in the hands of global financial markets.

China has to think about how it wants to reduce its vulnerability to USD-related financial sanctions at the same time it’s inevitably producing more geopolitical strife around the world as its economic mass and military capabilities increase.

To bypass that, they will think about free floating the RMB at the same time it’s in a position to dominate capital markets – i.e., rival the US’s position or exceed it.

China may be playing a strategy where it’s looking to free float the RMB at a time when its capital markets reach a critical mass relative to the size of global capital markets. Namely, the size of its capital markets in relation to the size of its economy on a global level.

Then it may look to liberalize its capital account and exchange rate.

That will be the point at which China may believe it’s immune from any currency market or capital market manipulation. The timeline for this is probably in the latter part of the 2020s.

What the loss of USD reserve status would look like and its impact

In terms of magnitudes of a loss in USD reserve status, you can look at the March 1933 and August 1971 USD devaluations and other cases.

The USD devalued a lot relative to gold but did not cause the US to lose its reserve status outright.

The situations behind devaluations are very different. Sometimes devaluations occur in terms of war outcomes or financial penalties that couldn’t be repaid and creditors wouldn’t materially relieve them.

Germany in the 1920s was one such case, where the war reparations payments from World War I were enormous and wouldn’t be relieved, as countries feared a rebirth of German militarism. They ended up with one of the most famous cases of hyperinflation in history.

Germany and Japan suffered wipeouts or near-wipeouts of their currencies after World War II.

And currency devaluations are always relative to something else.

Though the US has a financial situation where it’s overextended itself and turned it into a long-run game of money “printing” and currency devaluation to deal with all these IOUs, other developed market economies have the same financial pressures.

You can see this in their yield curves. When short-term interest rates and long-term interest rates are both around zero, then you can’t squeeze additional debt and money creation out of traditional monetary policies.

The US is there, as is the euro zone and Japan.

Devaluations throughout time are often looked at against something like gold, a type of hard currency-like asset with a track record as a store of wealth and transactional use going back thousands of years.

A depreciation of the US dollar against gold and other reserve currencies of 30 percent, for example, would be a big deal.

The US spends more than it earns and borrows from the rest of the world, and the US has built up a lot of IOUs and bonds that it sells to international investors.

If the US dollar has enough of an exchange rate depreciation to bring the balance of payments into equilibrium and foreigners lose confidence in the bonds they hold savings in (because they’re being paid back in depreciated money), that’s a problem for the US.

Then it’s a matter of what extra output is the US going to give to the world, or how much expense cutting can you do? You can’t raise productivity much.

It’s bad politically because at a basic level it means Americans will get to spend less. It’s essentially budget controls.

The US’s financial situation is a material risk to its currency over time and a devaluation is of significant possibility.

So those in the market who think long-term should want to insure themselves against this possibility in some capacity. Currency diversification is important. Putting ten percent of a portfolio in gold or thereabouts can be useful and a good start.