Price vs. Value: Understanding the Difference

What is the difference between price and value?

The price of anything is the money and credit spent on it divided by the quantity. While the value of something is often taken to just be the price as represented by a certain unit of accounting (dollars, euros, yen, pounds, etc.), they are different.

Fundamentals of price and value

When we think of “wealth” or “net worth” we often think of it in monetary terms. Namely, there’s a notional amount of assets denominated in money terms less liabilities (debt or credit instruments).

Money is something that’s liquid and can be easily exchanged to buy stuff. Credit is any type of claim on income that’s considered an asset. Even a stock can be considered a form of credit, as it’s a claim on goods and services at the most fundamental level, represented by the earnings derived from them.

Money (what payments are settled with) and credit (an IOU) can buy wealth (goods and services). So the amount of money and credit one has is a good barometer for wealth.

But wealth is not created by simply creating more money and credit. Wealth comes from productivity.

So it’s important to know that:

a) Most forms of money and credit don’t have any intrinsic value. It is simply created out of thin air as part of the system we’re in. Sometimes money is backed by a commodity – usually gold, and less commonly silver and other “hard” commodities – known as the “gold standard” to ensure that money has intrinsic value and there’s credibility behind it.

b) But in a fiat world – which is always ultimately desired by governments because it offers the liberty of money and credit creation as needed – money and credit simply serve as the basis for journal entries in an accounting system. The amounts can be changed easily.

c) The existence of money and credit is designed so we don’t have to physically barter goods and services for other goods and services. It’s impractical to do so; accordingly, we just agree on something portable that has value to exchange as part of a transaction. The basic purpose of using money and credit is to allocate resources as efficiently as possible to help productivity grow. When this occurs, both lenders and borrowers in that system are rewarded.

The relationship between money and credit and wealth creation (the production of “stuff”) is confused but is the largest driver of the economic cycles we face.

The cycle

Typically there’s a self-reinforcing relationship between:

i) The creation of money and credit, and

ii) the amount of goods, services, and investment assets that are created.

This makes them seem like they’re one and the same. But they’re different because money and credit aren’t goods and services.

There are two different economies:

i) A real economy

ii) A financial economy

Both the economy for “stuff” and the economy for money and credit are controlled by their own set of supply and demand factors.

The financial economy leads the real economy.

To illustrate this, take the example of the real economy when the demand for goods and services is rising and starts pressing up against supply.

When there’s a lot of demand for this stuff but only so much productive capacity – i.e., labor, technology, and capital to produce said things – the economy’s capacity to grow is limited.

If demand keeps rising faster than supply, it’ll push up the prices of goods and services – i.e., inflation will rise.

We have experience with this in terms of everyday goods and services we buy. We know that when we buy an airline ticket close to the day we need to fly, it’s likely to be higher because there will be fewer seats available. As the final wave of demand starts pressing up against the limited supply of seats, prices rise.

When inflation rises, central banks will typically want to tighten monetary policy. That means taking measures to rein in the supply of money and credit. That helps slow down demand in the real economy.

If the tightening of policy by central banks is happening faster than what’s discounted into markets, typically you will see the price of risk assets fall.

Therefore, you’ll see the impact in the financial economy before you’ll see the impact in the real economy.

Central banks operate this way, lowering and raising the demand for credit, with this eventually passing through into the real economy by lowering and raising demand for production.

Balancing the supply and demand of money and credit is hard to get perfectly right

This tightening and easing of monetary policy is done imperfectly, which is why we have business cycles that typically last somewhere around eight years, give or take a few.

As time goes by, it becomes more difficult to get the balance between output and price stability right as excesses build up and trade-offs become more acute.

Economies sometimes “overheat” – inflation becomes too high with respect to goods and services and/or financial assets – and the central bank tightens policy, which eventually leads to a fall in credit creation to produce a recession.

It then gets out of these, in normal times (when there’s sufficient easing capacity with room to cut interest rates), by lowering rates and pushing more money and credit into the system to get a rebound in demand.

Typically, the average recessions requires about 500bps of easing (5 percent lowering of the overnight rate).

The financial economy and the money and credit that makes it up is generated by central banks, which flows into financial assets. This produces lending that works to finance borrowing and spending.

The private credit system typically allocates this, with central bank interest rates working their way through the system to determine the rates on various types of lending that go on (e.g., mortgages, personal loans, business loans, etc.).

Monetary policy is broadest, fiscal policy can be more targeted

Monetary policy (controlled by central bankers) typically has the biggest lever on the system at the broadest level, but fiscal policy (controlled by politicians) is important too.

Fiscal policy can be more targeted, picking winners and losers in a more granular way. Monetary policy largely benefits debtors at the expense of creditors(and vice versa) and can benefit certain types of asset holders versus others.

Monetary and fiscal policy has a big impact on who gets the money and credit and the associated buying power that capital has. That, in turn, impacts what it’s spent on.

When interest rates are at about zero in both the short-term and long-term ends of the sovereign yield curve, that means traditional monetary policy doesn’t work as well.

The private sector also becomes less effective at helping stimulate credit creation because it lacks the incentives when nominal interest rates can’t be pressed down much more.

So governments take over more of the role in allocating money and credit. So capitalism as it’s typically known morphs into a type of “state capitalism”.

The value of money and credit

Creating money and credit without an offsetting commensurate amount of production devalues it.

The financial economy has its own supply associated with it. When a lot is created relative to the demand for it, its value will decrease.

Where it flows to will be important in determining what will happen:

- Does the money and credit being created go into creating economic demand?

- Or does it flow into other types of currencies and assets that are alternative stores of value?

If it goes into non-credit investments, then it fails to stimulate economic activity and causes the value of the currency to go down and the value of those alternative currencies and assets to go up.

These alternatives are typically things like other national currencies, gold and precious metals, commodities, collectibles, and now things like cryptocurrencies and other decentralized finance (DeFi) entities.

When these occur, you can get a type of phenomenon known as monetary inflation. This is when high inflation occurs because the supply of money and credit is high relative to its demand.

Most commonly, inflation occurs when there is high demand for goods and services relative to supply.

However, monetary inflation can occur even during times when there is weak demand for goods and services and the demand for assets is low such that the real economy is experiencing deflation.

This is how an economy can be in a depression yet experience high inflation at the same time. They are more common in emerging markets where debt is commonly denominated in a foreign currency.

But they can also occur in situations where debt is denominated in domestic currency, but typically when policymakers have already provided a lot of stimulation after a contraction and are starting to provide too much but to no avail.

Accordingly, it’s important to look at the movements in the supplies and demands of both what’s happening in the real economy and the financial economy.

The basic idea is that if you provide money and credit (demand) and there’s not enough offsetting production (supply), you get inflation. Money itself is not wealth.

Back to the price vs. value question

With the basic fundamentals considered, let’s get back to the relationship between prices and values.

They tend to go roughly hand in hand, similar to the real and financial economy, so they’re often confused as the same.

When people have more money and credit available to them, they typically spend more and more as a result. Put another way, if you give people more money and credit they will feel richer and spend more on goods and services.

When spending works to increase economic production and raise the prices of goods, services, and financial and investment assets, it appears that wealth is increasing. Those who own those things become better off in the way that wealth is nominally calculated or accounted for.

However, that increase in wealth is more illusory than reality because:

i) To the extent that the money and credit used to buy those things and push up their prices was funded by the creation of debt, it has to be paid back. When it has to be paid back, holding all else equal, that has the opposite effect.

ii) Because the price of something went up doesn’t mean the value of it went up.

For example, let’s say you own a house.

If the government produces a lot of money and credit and pushes it into the economy (directly or through financial markets via changes in interest rates or asset buying), that might cause the price of the house to go up.

But the house you own is still the same house. Your actual wealth didn’t increase. Only the way that wealth is accounted for has increased.

Likewise, if the government creates money and credit and all that goes into the purchase of goods, services, and financial and investment assets, that is likely to cause them to go up in price.

The amount of wealth as calculated in nominal terms increases but the amount of real wealth hasn’t gone up because you own the same thing you did before it was considered to be worth more.

Put another way, using the market values of what one owns to measure wealth gives the illusion of having more wealth, but that extra wealth doesn’t exist if you simply own the same stuff.

Big picture forces

In terms of the big picture economic forces, it’s the growth in productivity that makes the biggest changes over the long-run in terms of improving living standards. It’s essentially what an economy boils down to at the most fundamental level.

But over the short-run, the cycles matter the most. Money and credit is stimulative when it’s given out and depressing when it has to be paid back. Taking out debt is not only borrowing from a lender, you’re borrowing from your future self.

Once this process gets set in motion, you get the stimulative upswing, then eventually a painful downswing associated with too much debt and not enough income available to service it. And over the long-run, income must also be in line with productivity growth.

Accordingly, once borrowing starts happening where one can spend more than one earns only to have to pay it back in a future, that process quickly begins to resemble a cycle. So money, credit, and economic growth is cyclical.

If debt never exceeded income and income never exceeded productivity, our most fundamental big-picture economic problems wouldn’t exist.

Central banks have the biggest levers on prices (but not necessarily values)

Central banks control money and credit and vary the prices and availability of money and credit to control markets and that feed-through into the real economy.

When the economy is growing at a rate that will eventually cause it to run into capacity constraints and produce inflation, the central bank will want to tap the brakes.

It’ll make less money and credit (i.e., sources of demand) available, which cause both money and credit to become more expensive (i.e., higher interest rates).

When it becomes more expensive, less people want to borrow and spend and more want to lend.

When growth is too low – either a recession or growth is below economic capacity – they’ll want to make money and credit cheaper and more available. This incentivizes more people to borrow, spend, and invest.

The changes in the prices and availability of money and credit also cause the prices and quantities of goods, services, and financial and investment assets to change.

At the same time, central banks can only control the economy within their capacities to produce growth in money and credit. When interest rates are at or around zero for money and credit, they’ve reached the constraints of their ability.

They can literally give money away, but money and credit without positive real interest rates enters into a territory where money is no longer sound. That is, if no interest is paid on it, the incentives to hold it aren’t there.

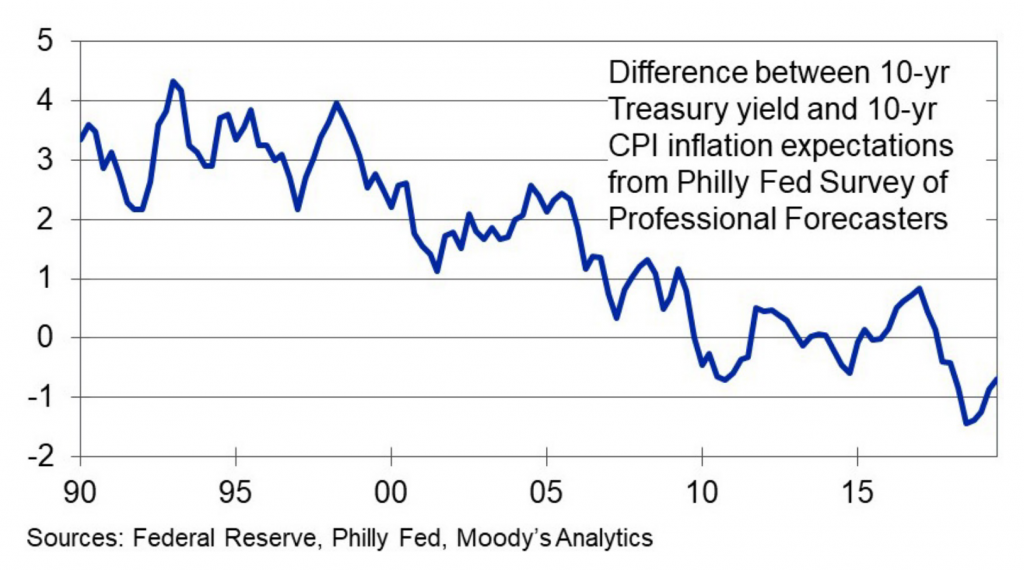

This is what’s going on in the US, most of developed Europe, and Japan – real interest rates are negative.

That can lead to currency devaluations and the movement of money and credit into other currencies and inflation-hedge assets. When this occurs the capacity for money and credit to aid in the ability to facilitate production declines.

This can lead to a dangerous self-reinforcing cycle of capital outflows, higher inflation, and currency devaluation. In the worst cases, there’s hyperinflation and the currency eventually needs to be phased out and replaced.

All currencies have devalued or died out over time. If you look at history every 300 to 500 years, you see that only around 20 percent of the currencies survive over that timeframe.

Gold is a rare exception that has been valued by societies for thousands of years. It is still used as a reserve (its current popularity only behind dollars and euros) and still has some use in international transactions.

It’s especially valued during war years when trust among countries is low. Countries with war reparations debts are commonly asked to pay in gold terms (or something that’s well-regarded as a reserve currency) to ensure they don’t simply devalue. Germany after World War I is a common example.

Some money and credit creation is good, but too much can be fatal

Money and credit creation seem good to most people because it relieves any debt and income squeezes that are going on.

It’s the most discrete and politically palatable of the main four ways of getting out of debt crises (austerity, debt write-downs and restructurings, wealth transfers, and money printing).

Moreover, it’s not obvious who is getting hurt by simply creating money and credit out of thin air and giving it away.

(The entities that are harmed are the holders of the debt and money. So those holding bonds and cash need to think carefully about what they’re holding and whether it will hold its value.)

On top of that, when a lot of it is being created that flows into various other types of financial assets – e.g., stocks, real estate, commodities – which makes their prices go up, at least in nominal terms.

People measure their wealth in the depreciating currency, so it appears they’re getting richer and they like that.

Few complain about all the money and credit being created. If anything, they want more of it and assert that the government would be stingy and inhumane if it didn’t do more of it.

There’s no acknowledgment that the government doesn’t have the money it’s giving out. The government is not some rich entity with bottomless pockets. It’s just a collection of people. It only seems rich because it can technically spend a lot.

But it’s borrowed money. The spending comes from debt. Debt eventually has to be paid back.

On the other hand, imagine if instead of printing money the government cut expenses to the level of revenue it took in to balance its budget and asked people to do the same.

Defaults and debt restructurings would stack up. Less spending would occur, which would result in lower incomes.

Or consider if they tried to tax people more, which is very hard to do past a point. Tax policy impacts capital flows and incentives.

People move themselves and/or their assets to other places to avoid them. If the tax impacts enough people, then people will only tolerate so much and throw out those governments imposing taxes that they don’t like and aren’t willing to pay.

If the new taxes impact only a sliver of the population (i.e., the rich), those big taxpayers will leave and policymakers will try to find creative ways to try to trap them (generally not very successfully).

So the path of least resistance is to simply provide a lot of money and credit and quietly ignore the matter of how it all gets paid.

And the policymakers in charge of these policies are typically only there for a very small snapshot of the country or empire’s history.

As a result, politicians don’t like to face limitations and trade-offs because it’s not politically popular to do so. There’s lots of talk nowadays about how you can print money and create debt with no consequences, but it’s not true. No entity can spend beyond its means forever.

So they usually don’t have the face the ultimate consequences of progressively indebted circumstances. The situation simply gets kicked down the road to new people.

Eventually spending has to get in line with income, which is a function of productivity.

The government plays a rule akin to the banker in Monopoly if it was possible to simply create more money and hand it out to everyone when too many of the players are about to go bankrupt and distributing the money helps to keep everyone going and pacified.

But it’s analogous to a Ponzi scheme because they’re just exchanging one liability for another.

How does it all get resolved?

The problem will be resolved through a weakening of the currency. It won’t come from more revenue and less spending to close the gap.

The loss of reserve status from irresponsible spending happens over and over again throughout history.

You eventually get forced budget controls one way or another. It’s the currency that’ll be the mechanism that’ll get things back in line.

Just like a person can appear rich by using a lot of debt to buy stuff, governments can be the same way.

The US, for example, has a negative net worth if you take into account not just the debt (household, corporate, government) but also all the unfunded liabilities. It only appears rich because of its current level of spending with money it doesn’t have.

The central bank’s role

As explained earlier, when central banks are faced with the situation of needing to fill in a gap due to a debt and income imbalance, it almost always prints money, buys the debt, and devalues the currency.

This becomes self-reinforcing because the interest rates received to hold the currency are not high enough to compensate for the rate at which the currency is depreciating.

The process of:

a) the central bank printing money, buying debt, devaluing the currency, and

b) the selling of dollar-denominated debt by holders of that debt as they put their assets in other things and the borrowing in the currency by debtors who take advantage of cheap inflation-adjusted funding rates to make high returns elsewhere…

…will continue on until there’s a new, appropriate balance of payments level.

This is another way of saying that there will be enough forced selling of goods, services, and investment and financial assets and enough curtailed buying of them by domestic entities to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

Cleansing the system of excesses to get back into equilibrium will be painful. One can expect lots of social and political conflict. Historically it commonly spills over into revolutions or civil wars.

There will be lots of blame going around over whose fault it is and lots of conflict between groups of people based on however each can be classed (left, right, rich, poor, and so on).

Basic portfolio strategy

This is why currency diversification is important and portfolio strategy should not be overly concentrated in any given asset, asset class, location or geography, or currency.

Betting too much on anything is risky and diversification and balance is going to improve a trader or investor’s risk/reward better than anything he or she can practically do.