What Is the Difference Between Money and Credit?

The price of a financial asset is money and credit divided by the quantity. So, understanding the two and the difference between money and credit is important to get at why financial assets are doing what they’re doing and help anticipate risk/reward in a market.

What is money? What is credit?

Money is what you settle your payments with. Credit is an IOU – a promise to pay.

Most of the standard money metrics – e.g., M1, M2 – are actually mostly credit. And most of the “money” in financial markets is actually credit, or an obligation that eventually has to be paid back.

An asset class where you see high valuations and lots of purchases on credit is especially risky.

Most financial assets are credit or equity obligations, not money equivalents

At any given time, the amount of financial assets relative to cash is large.

That means there’s a potential convertibility issue if everyone were to “run to the exits” at the same time (e.g., March 2020). When there’s a huge wave of assets for sale and not enough buyers, asset prices will fall.

They will fall until they reach a new equilibrium point on their own or the public sector (monetary and/or fiscal policymakers) will come up with new easing and liquidity programs to arrest the decline.

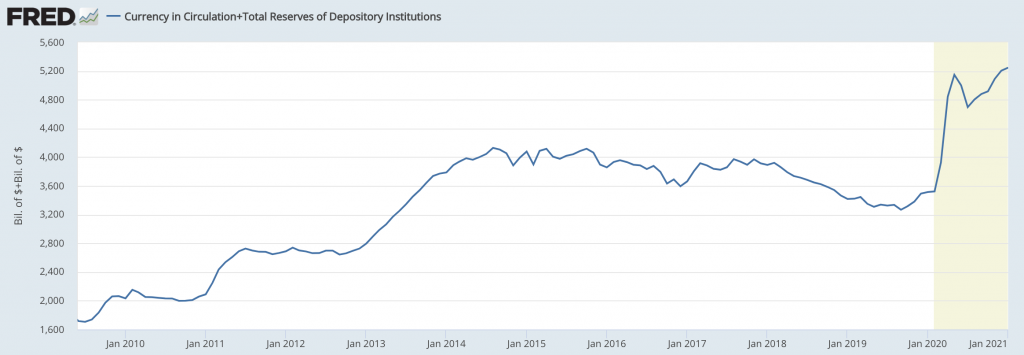

The total amount of money – i.e., currency and reserves (sometimes called M0) – in circulation was only a little more than $5.2 trillion at the beginning of 2021.

Currency and reserves in circulation

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

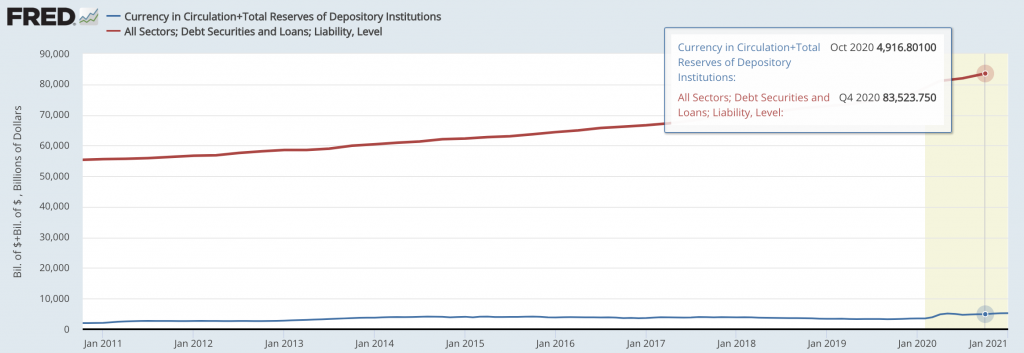

However, the total amount of debt in circulation was close to $85 trillion.

If you compare money (blue line) with debt (red line) side by side:

Total debt, all sectors (red) vs. Total money and reserves in circulation (blue)

If using these numbers for general illustration purposes, there are many more promises to deliver money (debt) than the actual amount of money available to deliver by a factor of about 17x.

On top of that, there is a lot of dollar-denominated debt that exists outside the borders of the United States. Accordingly, this 17x figure – claims on dollars in relation to dollars in existence – is small relative to the actual figure.

Foreign entities can decide to denominate their debt in dollars, but only the US central bank (the Fed) can create dollars. If their exchange rate falls relative to the dollar, that’s like an increase in interest rates.

The general idea is that there are a lot of goods, services, and financial assets being bought with credit and not enough attention to what they are promising to deliver and where they are going to get it from.

That’s why some traders will look at metrics like the total amount of margin debt being used. It’s a proxy for risk when more assets are being bought on credit rather than money.

The US stock market in the 1920s was fueled by lots of purchases of financial assets on credit. Margin requirements were lax, often as low as 10 percent. This means for every $100 of stocks that were purchased just $10 in collateral had to be put down.

Put another way, just a 10 percent drawdown could put you underwater entirely.

Bubbles commonly form in pockets of the economy when assets are purchased via easy credit and the cash flows are insufficient to meet debt servicing obligations.

There is much less money than there are claims/obligations to deliver it and many people begin going broke.

A lot of people think they are holding assets that they can easily convert into money, but this is only true on a limited scale. If a lot of people wanted to get out at once, this essentially results in a “run” dynamic where there’s no stopping it.

Any dynamic like this has to be rectified by getting more money into the system through central bank printing to buy the bonds. This keeps yields in check and devalues the currency.

This will also include restructuring debt and government finances. It often involves increases in taxes on individuals and/or corporations.

Credit helps explain why markets tend to trend over time

If you’ve looked at a chart of any financial asset, it may seem relatively random. But you’ll also notice that markets tend to move in trends over time.

Much of this has to do with the self-propagating process that comes with the creditworthiness of buyers in the market. It works on the way up and on the way down.

For example, early on after a bubble bursts, stock prices drop but earnings have not yet dropped materially. They usually fall later.

So, people tend to mistake the drop as assets being on sale.

Stocks may seem cheap relative to past earnings and expected earnings. This is because their prices have become cheaper, compressing their P/E multiples.

But the “buy at a discount argument” doesn’t take into account that prices fell because they’re discounting why they fell – earnings are likely to drop.

If the fall in earnings is under-discounted, then stocks will be more expensive relative to where they were when their prices were higher. After all, the fundamental purpose of buying a stock is to buy earnings.

This fall in prices becomes self-perpetuating because it sets off a spiral.

Wealth falls first, then incomes fall later.

As this occurs, creditworthiness – the ability to get credit – gets worse. This constricts lending activity. As lending falls, spending and economic activity drop.

As spending drops, corporate earnings fall and are likely to chronically disappoint.

This hits stock prices and causes more market volatility. More market volatility causes risk premiums to increase, which drives down their prices further.

Capital investment rates also decline. This, in turn, makes it less attractive to buy financial assets on leverage.

Some individuals and companies run into cash flow problems. Accordingly, they need to sell assets at cheap prices just to raise cash to pay their bills. This causes people to sell assets and prices drop further.

Traders and investors who are tasked with the buying and selling of financial assets also face the same problems.

Collateral requirements often increase and they need to dynamically hedge bets they assumed couldn’t happen (e.g., selling put options), which requires market makers to sell shares to hedge their liability.

Some will try to borrow the asset to short sell to cover their derivatives-related liabilities, which is the same effect. This compounds the sell-off.

All of these influences have an accelerating impact on asset prices, wealth, and incomes.

Money’s role in a transaction

Money helps facilitate payments, but it’s not needed to consummate a transaction. An economy really boils down to a series of transactions that take place.

For example, let’s say I paint houses for a living and you build furniture.

If I need furniture and you need your house painted, we can agree to exchange a certain amount of each service/goods and call it even. No money needs to be exchanged and we both benefit.

Whatever the commensurate value of that activity is will be booked into GDP, expressed in terms of the prevailing unit of account (dollars, euros, pounds, etc.).

Alternatively, if I need furniture but you don’t need your house painted – or if I’m not the service you want – I can agree to pay for the goods with money or credit.

If I pay with money, the transaction is settled on the spot.

If I pay with credit, is the transaction settled? No; I’m basically saying I’ll pay you later.

This opens up a credit liability for me and you have a credit asset.

At a later date, I pay the bill with money. Debt is a “short money” position. It eventually has to be covered.

You can think of various instances where there are reciprocal exchanges of value that don’t involve money. This can be a neighbor doing something for you and you returning the favor. Or exchanging goods that each wants. Both got value even though no money was involved.

Though in most cases it’s better if money is involved in a transaction to more easily facilitate and simplify the exchange.

Money is just a construct so we don’t have to physically barter, and it also has use as a store of value.

On its own, money is inherently worthless. If the supply of money rises faster than productivity outcomes, it becomes devalued. An inflation rate that is low and steady is healthy for an economy. But it’s unhealthy if it becomes too high.

It’s underlying productivity that gives money its value. The reason why living standards tend to improve over time is because we learn more, invent more, and are able to do more over time. More knowledge is gained than lost.

This is why for policymakers it’s not simply about creating and giving away money, but about finding ways to better foster productivity. Money and credit growth in excess of productivity growth simply devalues it.

It is essential that the debt and money created is used to produce productivity gains and a favorable return on investment. If the cost-benefit analysis is ignored or deemed unimportant and money and credit is given away that doesn’t yield productivity gains, the devaluation of this money and credit will reduce the buying power of the government and everyone else.

It is perfectly appropriate for the central bank to create money and be the lender of last resort so long as the capital is invested to have an ROI that is large enough to adequately service the debt.

If incomes never exceeded productivity, and debt growth never exceeded incomes, virtually all of our big cyclical economic problems would never occur.

Conclusion

Money and credit both convey buying power but they’re both very different.

Money settles a transaction while credit provides a promise to settle the transaction at a later date and/or over time.

When a lot of financial assets are bought on leverage it creates a double-edged sword of higher overall prices, but more overall risk.

For example, most holders of debt assets – bonds are the deepest asset class globally – believe they can sell them to get cash and to buy goods and services with it. That’s the basic purpose of holding financial assets – to convert them into buying power in the future.

However, especially with bond valuations where they are currently, it’s not realistic for a lot of these bonds to be converted into cash to be used to buy goods and services.

This goes for any asset of a financial character, including equities, housing, private businesses, and so on.