Venture Capital: Valuations, Portfolio Construction & Risk Management

Venture capital and angel investing largely involves investing in startups. While venture capital is a specific type of investing, it’s not exclusive to anyone.

Investing in early-stage projects can offer alluring yields and can be part of anyone’s asset mix, even day traders. In the end, it’s a just-make-money game.

While some people prefer stocks and some prefer real estate or other types of investment assets, early-stage investing may be the preference – or a bigger part of the mix – for others.

Venture capital typically involves technology investing or funding newer types of business “disruptive” models (e.g., fintech). But it can practically mean investing in any business no matter what vertical.

Startup valuations

One of the most common and expected questions in the venture capital space relates to how startups are valued. In the end you have to know what you’re paying for.

While you can invest in a stock or liquid instrument for reasons that have little to nothing to do with value, it’s often a different story for startups.

Early-stage companies are the riskiest. They don’t have the track records of older firms.

With a company like McDonald’s (MCD), it’s fairly straightforward knowing roughly how much in earnings it’ll produce on an annual basis. Then you can calculate your yield from the investment.

But with a limited operating and financial history for a startup, there are many unknowns.

Some venture capitalists (VCs) will bet on the founder or team. It’s one of the data points that can be pretty reliably known.

Do they have a track record of success in whatever they’re trying to do? Have they built and scaled something before?

If not, do they have other things in their favor, such as a deep understanding of the market and what steps they need to take to get the business off the ground and viable?

As a VC, can you create synergies in your portfolio with what you might be investing in? Can one project help the other in one or more ways?

Do you have the expertise to add value to the business? Many VCs are former entrepreneurs and have run businesses themselves.

But any early-stage company will deal with various uncertainties and many things that could undermine it.

And anything with a lot of uncertainty will have lots of disagreement about its valuation. This goes for volatile public companies and also goes for technologies and inventions that are not widely accepted, such as bitcoin and cryptocurrencies.

This is especially true for businesses with very difficult unit economics that have yet to show sustainable business models, unlike companies that are effectively consumer staples.

Tesla (TSLA) is more volatile than McDonald’s or Apple (AAPL).

The main forces that determine how VCs think about startups are the following:

i) Sector, vertical, or industry

ii) What’s the market size, how fast is it growing, and what’s its potential?

iii) Does the project have a realistic path to getting its products and services to market?

iv) How are comparable firms trading (e.g., sales multiples, by number of users)?

v) What kind of competition is there among investors?

vi) Does the entrepreneur/company have a more pressing need for funding that could help the investor get a better deal?

Types of valuation models

These valuation models can go for not only startups, but for later-stage companies as well.

Comparable Company Valuation (“Comps”)

Comparable company valuation – often simply called “comps” – is a method where analysts and investors will look at companies with similar business models to determine a valuation.

They will use various appropriate financial ratios to find lower, middle, and upper ranges for the valuation of the targeted company.

Many early-stage companies want to grow a lot and aren’t focused on what kind of income (dividends, distributions) they can give back to their owners. Instead, they want to invest as much as appropriate to grow the business and reap the rewards later.

So, they will often go with something like a forward revenue multiple.

For this, to come up with an estimated enterprise value (the sum of any equity and debt financing) you take a revenue figure and apply the appropriate multiple.

For example, if a company is expected to take in $1 million in revenue and comparable companies are looking at private or public valuations of about 10x their revenue figure, then the total value of that company might be considered to be about $10 million.

Other companies might use more specialized multiples.

Many internet startups will look at daily or monthly active users, such as EV/DAU or EV/MAU.

These are often used for sites or apps that have been sparsely monetized. So in this case a revenue or any type of operating profit figure wouldn’t be very useful.

A VC might look at an internet startup’s monthly active users, look at the median multiple of comparable companies and use that to obtain an approximate valuation.

If a company learns how to monetize its user base better over time, the value per MAU might increase.

For example, way back in 2014, WhatsApp was valued at around $40 per MAU. That’s quite a bit considering the company didn’t monetize its user base back then.

Is it possible to get $40 of value from each monthly active user over its lifetime?

It’s a possibility if there are synergies with other parts of the portfolio. WhatsApp is owned by Facebook, so there is a lot of value in the data and how that can go to help advertisers get more bang for their buck relative to traditional channels.

But using monthly active users is also very crude valuation-wise. Many users are worth nothing.

There’s a wide range of outcomes. Ultimately whether the business model is workable comes down to the lifetime value of each customer (LTV) minus the customer acquisition cost (CAC).

That number must ultimately be positive. Having a high number of users helps, but they must be efficiently monetized in order for the business to work.

Discounted cash flow (DCF)

Discounted cash flow (DCF) gets at the heart of what makes a business what it’s worth.

A business’s value is the discounted present value of future cash flows.

In other words, a business that ultimately has value makes a certain amount of profit each year. All of those cash flows – the amount of cash generated by a business in a specific period (quarter, year, etc.) – are then discounted back to the present through a discount rate that represents a desired rate of return.

A dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future, so all those future cash flows come with a discount rate to account for that.

You add all those up and that’s your valuation.

In the numerator, you have a cash flow. In the denominator, you have the discount rate.

The discount rate doesn’t have to be from the academic constructions, such as the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) or multi-factor models (e.g., Fama-French). In business, those are virtually never used.

It’s up to each person to determine how much return they need from a particular investment. So the discount rate is idiosyncratic. In any market, different people have different motivations, goals, and time horizons.

Like all traders and investors, returns will need to be proportional to the risk taken on.

Cash and bonds are considered the least risky from a volatility standpoint (though they have dangers of their own, especially if their yield is low and the currency is being devalued).

Stocks have more risk than cash and bonds. And leveraged and riskier equity forms – e.g., private equity, venture capital – are riskier than those.

An early-stage pharmaceutical company whose revenue is planned on just one product is going to be very risky and has a high chance of failure. So, a VC is going to effectively assign that a very high discount rate, in effect.

They want to keep their downside appropriate while keeping the high upside, since the company itself is an option bet on the future.

Discounted cash flow is not always particularly relevant for startup firms because they may not be generating cash for many years in the future.

Moreover, early-stage companies often don’t have stable operating performances when they’re growing a lot even if they’re navigating them successfully.

With the inherent wide range in future financial performance, using the DCF valuation technique is somewhat rare for early-stage firms. This is especially true when it’s expected that the cash-generating phase of the business is more than five years out.

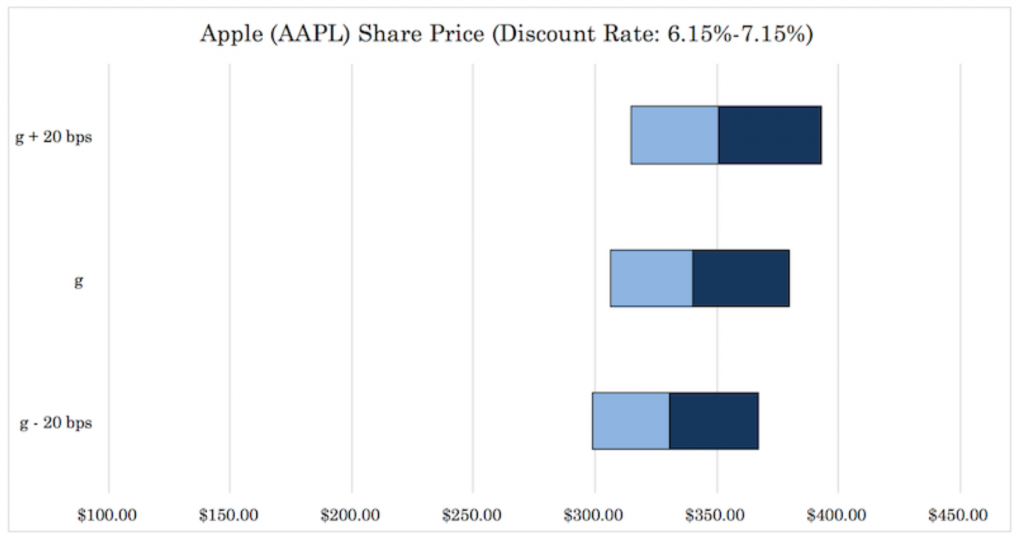

It’s also important to note that when analysts do DCF, they will practically always state their valuation as a range, not a precise figure, sensitized to different performance or discount rate factors.

This is often shown as a “football field” graph to show low, middle/median, and high estimates for the valuation.

We showed one such example in our article on Apple (AAPL).

First Chicago Valuation Method

The First Chicago Method combines different approaches and comes up with a valuation based probabilities of various scenarios working out.

It expresses valuation as a range, generally with three different scenarios:

- base case

- bull case

- bear case

Valuation might be through discounted cash flow or a comps/multiples-based approach.

It is common to allocate a probability to each valuation scenario under consideration.

For example, an analyst might see a 40 percent chance of the base case occurring, assign a 10 percent chance to the bull case and 50 percent chance to the bear case to express that the downside risks for the business are quite high and asymmetrically skewed, especially for an early-stage company.

Those probability-weighted averages form a range and then can be used to derive a median estimate.

For instance, let’s say the base case scenario is that the company grows into a $50 million valuation.

The bull case is a $250 million valuation.

The bear case is failure ($0) since the reality is that many businesses don’t work out long-term and have ultimate valuations of zero.

The probability-weighted valuation would come to:

Valuation = $50mm * 0.40 + $250mm * 0.10 + $0 * 0.50 = $45 million

As a result of that $45 million figure, an investor might want to offer $4.5 million or less for 10 percent equity as an example deal.

Venture Capital Valuation Method

The venture capital method works by imagining the end result and then working back to a present valuation.

For example, let’s say you wanted to estimate what a company could be earning 20 years in the future.

That would be enough time for it to seize a realistic share of its market and start earning profits if it were to succeed.

For public equities, the long-term average multiple is generally around 17x over time. Or one could simply take the current earnings multiple of the market.

Using an earnings multiple that’s specific to a certain industry is also perfectly normal, as auto companies trade at very different multiples than tech companies, for example.

You would then discount all this future value back to the present using the kind of return you’d like. This could be expressed as an internal rate of return (IRR) or ROI.

If you believed that a company could be worth $1 billion in 20 years time if it reaches its realistic potential and want a return of 15 percent annualized over that time, you would determine its present value as:

Valuation = $1 billion / (1+0.15)^20 = $61 million

If you wanted a 10 percent equity stake, you could then offer about $6 million or less.

If the company wanted to raise more capital and you wanted to be more prudent about not getting overly concentrated in one investment, you could ask to pay a lower amount for each additional unit of equity you take on in the company.

If the company wanted to raise $10 million instead of just $6 million, that would come to around 16 percent of your expected potential value of the company.

Supposing you were willing to pay $6 million for 10 percent of the company (which comes to $600k per one percent of the company’s equity), you might be willing to go up to $10 million if you wanted 20 percent ($500k per one percent).

That would give you higher upside but also limit your concentration risk as well as your overall downside risk per unit of upside.

Another possibility is to add conditions into the agreement to protect against downside, such as a liquidation preference provision. This would help get you your initial investment back should the company later be sold at a lower valuation.

Understand what the company is doing and how it will/could make a profit

Venture capital has a lot to do with ideas (some unproven) and dealing with many variables that aren’t known. It’s less mathematical than other forms of trading and investing (e.g., bonds).

More important than valuation models themselves is understanding what the business is doing and how it could make money.

Extensive financial modeling can be used to help understand possibilities and map out a distribution of potential outcomes.

But some are better at imagining possibilities than they are with details of trying to get more precise with things that are not imminently important.

In fact, much of the early-stage realm is about the narrative and getting investors behind the vision or possibility that there’s something big that could develop.

For example, Nikola (NKLA) and many green energy transportation companies were able to raise lots of money and even go public before they even made revenue, let alone begin talking about the notions of having respectable margins and a viable business model.

At the basic level, how will a business create value for its customers?

How will it save them time, money, or give them something that society values more broadly?

So it’s important to understand how the company generates revenues or intends to generate revenues in the future.

Many startups are able to successfully create a product(s) and/or service(s) that provide something that customers need. But they have trouble with monetizing the idea.

Some services know they have a service that they can’t directly monetize but don’t have sufficient scale to make it work with ads – i.e., the traditional business model of “free” platforms (such as Facebook or Snapchat).

Snapchat, Twitter, Whatsapp, Pinterest, Facebook/Instagram and other communication and sharing platforms are able to provide value in excess of inbuilt messaging apps on mobile phones.

But monetizing these platforms can be difficult.

Users generally won’t pay to use them, either as a one-time fee or a recurring subscription fee.

If they try, most of their user base would dry up and there are always competing projects that will provide the service for free.

There are apps like (e.g., games, dating apps) that offer freemium models, where a limited version of the app is free with ads while they provide value-additive services for a fee that helps with overall functionality.

Advertising is easiest because:

- You don’t have to charge your user. They can choose to ignore or skip the ad (or possibly block it).

- You don’t have to come up with your own products or services.

- It’s relatively passive.

Social media platforms can also generate revenue streams from enhanced listings, connecting them with their target audience, sponsored promotions, and other methods.

Whatever the revenue stream, valuations can be built out given estimations of revenues and costs using a combination of drawing on information from other companies, market size, growth in the market, and all other evidence that may be helpful.

Venture Capital Portfolios

Angel investing and venture capital is one of the riskiest forms of investing. The failure rate of startups is very high.

It’s not uncommon for early-stage investors to write off 50 to 80 percent of their investments, either recouping nothing or very little.

Another 20-40 percent of those investments may do well but not great.

And realistically less than 5 percent will provide the type of big returns (10x, 100x, or more) to give the type of returns necessary to excel.

Calculating performance relative to traditional trading and investing

If your general breakdown over 10 years is the following:

- 65 percent are failures (zero return)

- 30 percent are breakeven-ish (1x returns)

- 5 percent are 100x returns

Doing the math:

Money-on-money (M/M) multiple = 0.65 * 0 + 0.30 * 1 + 0.05 * 100.00 = 5.3x

That 5.3x multiple over 10 years is equal to:

Annualized return = 5.3^(1/10) – 1 = 18.1 percent

That’s respectable and those are good returns. But it also shows how reliant these kind of portfolios are on the home runs and grand slams.

What if you don’t hit as well on the big winners?

If the 100x return list dropped to just 3 percent from 5 percent and your representative breakdown looked like this, how would that impact your total returns?

- 65 percent are failures (zero return)

- 32 percent are breakeven-ish (1x returns)

- 3 percent are 100x returns

Money-on-money (M/M) multiple = 0.65 * 0 + 0.32 * 1 + 0.03 * 100.00 = 3.3x

That 3.3x multiple over 10 years is equal to:

Annualized return = 3.3^(1/10) – 1 = 12.7 percent

If it fell to just 1 percent from 5 percent:

- 65 percent are failures (zero return)

- 34 percent are breakeven-ish (1x returns)

- 1 percent are 100x returns

Money-on-money (M/M) multiple = 0.65 * 0 + 0.34 * 1 + 0.01 * 100.00 = 3.3x

That 1.3x multiple over 10 years is equal to:

Annualized return = 1.3^(1/10) – 1 = 3.0 percent

Then your returns look a lot more bond-like despite all the overall risk you’re taking on.

Venture capital investing is a lot like buying OTM options.

Most won’t work out, so your failure rate will be high. Some will provide wins but not of much scale. Then there are the rare ones that make you back many multiples of your original investment (i.e., premium paid in the case of options).

Diversifying is important. That can mean investing in different types of businesses with different environmental sensitivities.

It might mean investing in companies that can provide synergies with existing portfolio companies. How can they help each other generate higher returns?

It might also mean having venture capital/angel investing being only a part of a portfolio.

You can still invest in stocks, fixed income, real estate, and other real assets, alternative currencies and stores of value, and/or a core business or skillset that you’re really good at.

Having things that are stores of value – i.e., they reliably increase your purchasing power over time – and less correlated to equity-related investments will help improve a portfolio reward/risk profile and help smooth out the fluctuations in a portfolio’s value.

Additional considerations

Venture capitalists and angel investors also have to deal with their capital being locked up for longer periods of time.

Many venture capital funds have lock-up periods of 5-10 years. This is also true for hedge fund and private equity investments.

This helps investors avoid having to worry about redemptions and volatility in their assets under management (AUM).

That way their overall strategy isn’t disrupted by the whims of so-called “hot money” – entities that pull their investment during any inevitable imperfect stretch of performance.

Having a large part of your net worth is one startup or just a few can provide more right-tail risk (positive upside), but it generally isn’t worth the left-tail risk.

This is especially true as your time horizons shrink or you have certain life circumstances that encourage a more conservative approach, related to age, dependents, fixed spending requirements, and so on.

Anyone with a large fraction of their net worth in one particular asset should ideally hedge that in case things sour in the future. That can mean diversification or it can even mean an outright hedge.

For private companies, an investment bank or insurance firm can design a type of product to help accomplish this depending on the size and nature of the business.

In some cases it’s hard to design a pure hedge.

If you’re a private packaging business, it’s feasible that you could buy put options on public packaging companies to help offset your risk.

An oil exploration company might buy put options on the price of crude oil and other products they’re involved in to help protect their business against unexpected falls in their prices.

Buying stocks might not be the best way to hedge. It can diversify to an extent, but the correlation between public equities and private businesses is quite high or at least not particularly reliable.

Moreover, some who are active in startup investing don’t have sufficient cash because so much is tied to illiquid investments. This can be true for venture and private equity investors. It can also be true for real estate investors who own illiquid investments, typically on leverage.

If something happens where cash flow is hit (e.g., a bad recession) or the value of their collateral goes down a lot, it can be very dangerous.

So even though valuations can be quite high, so much of this “wealth” is actually illiquid.

It can be a large paper amount, but the amount is cash can be very small and result in a squeeze if expenses or payments are too high relative to income, cash, and sales of available liquid investments.

This can be offset to some degree by:

- Reducing one’s concentration (diversifying)

- Hedging in reliable ways (something with inverse exposure – e.g., put options, shorting something)

- Having ample liquidity (cash/liquid reserves) to prepare for any downturn

Like with anything, don’t invest anything you can’t afford to lose. With stocks, your downside is high, but it’s rarely zero, especially if you’re using index funds.

But with venture capital and angel investing, your downside is quite often and realistically zero.

This is also true for anything that employs lots of leverage. If you’re leveraged 4x, it only takes a simple correction (10 percent drop) for 40 percent of your wealth to be wiped out. A bear market (20 percent) means you’re at risk of getting wiped out altogether.

And this generally happens at the worst time – when assets get cheap and it’s a buying opportunity.

Also recognize that illiquid investments can be hard to sell.

A stock you can liquidate during various hours of the day/week. A piece of a private business, real estate, physical asset, etc., is a different story.