Wealth Tax and the Stock Market

Taxes are an important part of the conversation for risk asset markets, as they impact their valuations. They influence capital flows between countries, as lower forward returns in one country via tax changes impacts investment decisions.

It’s an important consideration today, as countries and local governments face large revenue shortfalls.

Policymakers will be forced to think about how to raise more taxes and how to do it in an efficient way.

They will also have to think of matters regarding:

– who they raise taxes on (typically those with high incomes as they have the most to “contribute”)

– through what channels – e.g., income, capital gains, real estate, inheritance, sin taxes (e.g., gambling, pollution or activities with negative environmental outcomes), and

– how to do it without undermining productivity

Wealth tax vs. income and consumption taxes

Taxation typically targets income and consumption, as these are the most liquid sources.

Sometimes they target wealth, or a percentage of the notional value of various assets. However, wealth taxes rarely work well because much of what we know as wealth is illiquid.

In the United States, wealth taxes have been deemed unconstitutional and such a ruling would be required to be overturned by a court for them to be implemented. But they have been applied to varying extents in other countries and throughout time.

In the 2020 US election, wealth taxes became a subject of focus on the Democratic side. Two candidates, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, used the idea of wealth taxes as part of their campaign. Not unsurprisingly, they were considered the two candidates least friendly to asset markets.

Wealth tax: historical precedents

After World War I, Germany was faced with a large war reparations debt that effectively couldn’t be defaulted on. It was to be paid back in gold to prevent the country from essentially printing their way out of it by servicing it in depreciated currency.

Facing the government’s huge need to collect a lot of revenue, in 1919 and 1920 various new laws were put into place to create a variety of new and complex taxes.

Germany’s finance minister at the time, Matthias Erzberger, wanted to effectively abolish the concept of a rich individual. (Due to modern-day wealth gaps in many developed countries, this is a similar theme held by some individuals today, resulting in some level of re-emergence in the wealth tax concept.)

In December 1919, the government passed the “Extraordinary War Levy for the Fiscal Year 1919” following the “War Levy on Capital Gains” in 1917 to create wealth taxes.

These scaled progressively. At five thousand marks, wealth taxes were levied at 10 percent, going up to 65 percent above seven million marks.

Based on estimates done by the Reich government and its economists at that time, the tax was expected to transfer nearly one third of all German wealth from the private sector to the government. This would then be used to service the state’s war reparations debts.

However, because most wealth is not in the form of cash, many of those subject to the tax had trouble converting their wealth into money. This was true both in terms how fast assets could be turned into cash and the act of selling off assets to raise the cash in the first place.

When assessing a wealth tax on a tangible asset or private business, that valuation is typically subjective and not known with a high level of accuracy. Determining the true valuation of an asset means it may have to physically be sold. It many cases, this is not practical or desirable.

Moreover, keeping track of asset inventory and valuing the broad range of assets that could be considered a source of wealth means a large bureaucracy is needed to administer the program and ensure compliance. That can wildly bloat its cost and undermine its effectiveness.

Because of the illiquid nature of most wealth, the Reich had to permit payment by installment. In some cases, payments were to be spread out over 28-1/2 years. Many land and real estate-related property tax payments could be spread out over 47 years.

The government effectively treated these debts as “mortgages”.

Additionally, out of sheer need, the government proposed that more of the equity in public and private companies should be provided to the state. (Because the government was hamstrung by impossibly large debt servicing, they could not “print” their way out of their debt, making their proposals increasingly aggressive.)

By the summer of 1921, the country’s lawmakers could see that generating adequate income from wealth taxes on the rich and businesses was difficult and not going according to plan.

Because of the destruction brought on by the war that had ended 2-3 years earlier, incomes were still depressed relative to previous levels. Taxing wealth, again given its nature of being heavily illiquid, didn’t do a good job of collecting the income needed in the present. Many attempts at expanding the wealth tax were blocked by those with influence.

The government decided to undo many of their laws and ideas regarding wealth taxation due to its inefficacy and moved more in favor of taxes on consumption goods.

As a source of liquidity, collecting taxes on consumption were more effective.

At this point, the high tax rates on the wealth were being passed in conjunction with declining net worths as the value of their investments was being eroded due to a bad economy. This caused them to desperately attempt to preserve their shrinking wealth in any way they could, leading to unlawful tax dodges and pulling their capital out and moving it (and often themselves physically) to other countries.

The “Reich Emergency Contribution” taxed wealthier individuals as part of the new tax reforms. Any pre-existing tax liability was also payable through a series of installments. In other words, it effectively became a recurring charge on wealth. This was added on to wealth holders’ existing liabilities under the “War Levy” of 1917 and “Defense Contribution” of 1919.

Due to inflation and the different means of valuing property, industrial plants, and other tangible assets, those who owned wealth in financial form (e.g., stocks, bonds, loans and mortgages) were hit harder by the set of legislation than landowners, industrialists, and those whose who had their wealth heavily comprised of tangible assets.

At the time, lawmakers and economists recognized that the claims on those who held financial assets were too large to be paid out in the manner promised, assuming the value of money were to be maintained.

This led to a pivot toward accepting inflation as an implicit means of taxation. In other words, inflation could be used to help debtors by reducing the real value of fixed-rate liabilities and a discreet way of creating an easing of policy.

When a government owes debt, there are three ways it can be taken care of:

a) cutting spending

b) raising taxes

c) printing money

The former two have limitations in terms of splitting the pie up and getting more revenue into the public sector and away from the private sector. The latter’s limitation is in the form of currency weakness and inflation.

Countries with reserve currencies – e.g., there is large global savings in them; namely, high demand for the country’s credit – can push the limits on printing more than those without one. In other words, it’s a special privilege to have as it can be used to derive an income effect (namely, cheaper borrowing and greater borrowing capacity).

Even countries without reserve currencies will be tempted to print money due to the contractionary nature of spending cuts and raising taxes. Printing money has stimulative effects as it increases the amount of currency in circulation and a currency devaluation can make a country more competitive in the global markets (i.e., its goods are cheaper in relative terms).

But countries also need to be careful because currency devaluations are zero-sum in nature. In times of global economic weakness, most countries don’t want a stronger currency to ensure trade competitiveness and a general need to ease policy.

If a country devalues its currency and its trade partners respond in kind, it may not make a difference. Yet imports may become more expensive, creating inflation as these costs are typically passed off to consumers.

In such tit-for-tat “currency war” cases where central banks follow their trade partners down to avoid putting themselves at a competitive disadvantage, the positive easing effects from a devaluation may be wiped out yet still be stuck with the adverse inflationary effects.

For this reason, monetary authorities would prefer to ease policy through the domestic interest rates and credit channel if they can. They do this by lowering short-term interest rates, then long-term interest rates by buying its own sovereign bonds when short-term interest rates can’t be pushed down much further.

Only when the credit channel is exhausted will they move on to other tactics like large-scale debt restructurings and currency devaluations.

For traders, this also means currency volatility will tend to pick up when the rates and credit channels can no longer be pushed down to stimulate money and credit creation (when rates and the yields on longer-term debt are zero or a bit below).

The exception is if economic volatility picks up when policymakers need to defend their currency within a band, such as in the case of a fixed-exchange rate regime.

The Reich wanted to convert its longer maturity debt into short-term bills and/or redeem long-term debt prematurely at par value via cash issuances by the central bank. This plan of eliminating long-term debt could eliminate the prospect of bankruptcy.

As one Reich official put it, it was more advantageous “to take advantage of the full opportunities afforded by money creation than to handicap the forces of production and spirit of enterprise through a confiscatory tax policy.”

As many know, Weimar Germany went on to have bad inflation problems. This turned into a full-blown hyperinflation in 1923 that eventually wiped out the currency and virtually all financial wealth within the country.

It was virtually impossible for the Reichstag to pay back the sheer level of internal and external debts required that could neither be “printed out of” (because they were to be paid in gold) or defaulted on.

Any attempt to service it would have been impossible, let alone pay it off in full. The government would inevitably print money. But the external gap was so severe that they would inevitably face very bad inflation problems.

This is not simply an observation of Germany at the time, but a universal reality when not enough income can be collected to be paid on debts or other liabilities that must be paid back in non-depreciated currency. They trade-off is either a collapse in economic activity or a printing of money that results in runaway inflation.

Those at the time reasoned there could possibly be some level of partial relief. And there eventually would be.

But other powers globally held Germany’s feet to the fire despite an inevitable eventual humanitarian crisis to prevent a rebirth of the state’s militarism and the potential uprising in global conflict that it would bring. This eventually happened anyway the next decade.

Virtually no one wanted to save in the Deutsche mark currency, fearing the government would print a lot of it and deprecate its value. Given the impossible mountain of debt to service, it could (and eventually did) render the currency worthless.

Printing indefinitely, while bad, is often seen as superior to ceasing printing altogether and getting a complete drying up of economic activity.

General wealth tax takeaway from the Weimar example

There are many historical examples of wealth taxes. The general point from the post-WWI Germany case is that they are very hard to successfully implement and raise revenues on much of a level given the illiquid nature of wealth.

When those targeted – mainly the rich or anyone who owns assets more generally – fear that their wealth will be taken without benefit in return and/or they will be treated with hostility, this causes them to want to move their money, assets, and themselves to places that are more hospitable.

If continued, policymakers will notice the loss of these big taxpayers and will increasingly want to find ways to trap them. This reduces the tax base and spending revenues in the locations implementing these plans, and forms a classic “hollowing out” process.

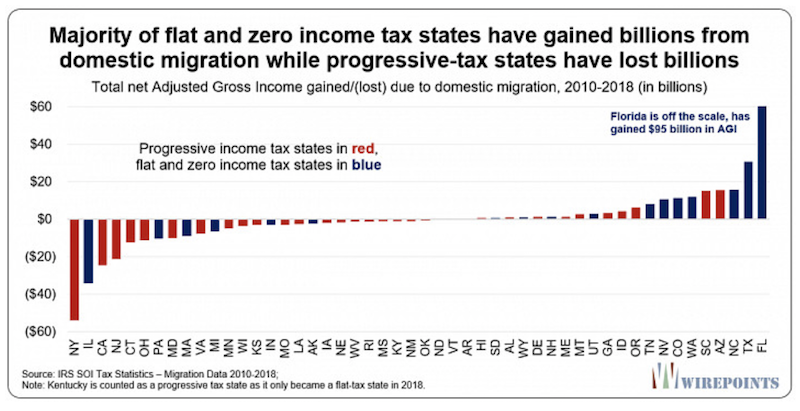

Within the US

The United States is experiencing the classic capital flight process to some degree at the state level.

The rich are leaving higher-tax states where there is financial stress (e.g., Illinois, California, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut) and higher wealth gaps, and moving to state where there is zero state income tax like Florida and Texas, in particular.

This process tends to go on in a self-reinforcing way.

Fewer tax revenues weakens local or domestic conditions. This raises tensions and calls for state officials to raise taxes to make up for the shortfall. (State and local governments, of course, have no influence over the monetary system.)

This causes more emigration of the large taxpayers and further worsens conditions, and so forth.

When outflows are bad enough, governments will no longer want to allow these forces to continue. In other words, the capital outflows out of the locations, assets, and/or currencies experiencing them will be targeted for control.

But just the act of trying to control capital flows incentivizes people to want to get their money out to protect themselves. It’s similar to how people want to pull their funds out of banks if there’s the notion that it could restrict access to people’s money and/or go under, creating a “run” on it.

Wealth taxes and asset valuations

The nature of how wealth taxes influence asset valuations is complex and doesn’t have a straightforward answer.

Politicians that run their campaigns on wealth tax promises will have their plans discounted into markets ahead of time.

For example, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren ran populist-left campaigns, promising to levy higher taxes on high-earners and corporations while implementing wealth taxes as well.

The extent to which their proposals get baked into asset markets is a function of:

a) the details of the proposals – e.g., how much (flat, progressive), what asset classes, when, etc.

b) their odds of winning their party’s nomination and odds of winning the presidency thereafter in the general election

c) the odds of their proposals being implemented, which is a function of:

– how sincere their policy proposals are (what they say publicly versus what they do in reality due to the influence of donors, lobbyists, and special interests)

– the degree to which it’s constitutional (i.e., is it likely to be partially or fully struck down in the court system), and

– how likely it is to get passed (which means the probability of a House and Senate that will be compliant with passing such ideas into laws)

The market will also have to take into account second-order effects:

Since wealth tax expansions usually partially or fully fail when enacted, there’s the effect of how likely it is that such proposals would be repealed.

When the ideological pendulum swings one way, the excesses of such a shift are likely to be met with disdain (and the flaws of the opposite side forgotten over time), increasing the odds that it swings back the other way.

The vast majority of wealth is not money

Some wealth tax proponents tend to conflate wealth with money. Very little wealth exists in the form of cash.

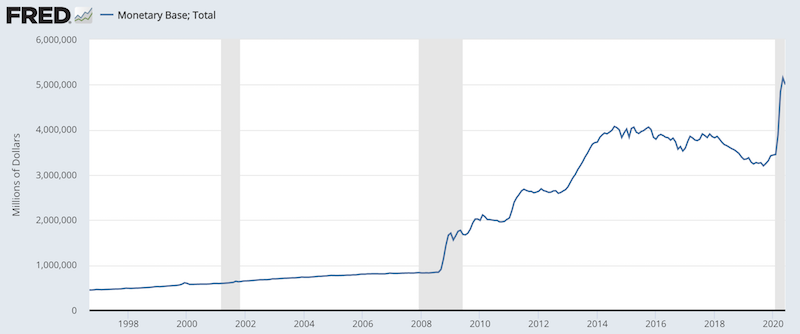

If we look at the total monetary base in the US – currency and reserves in circulation – it is only a bit over $5 trillion.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

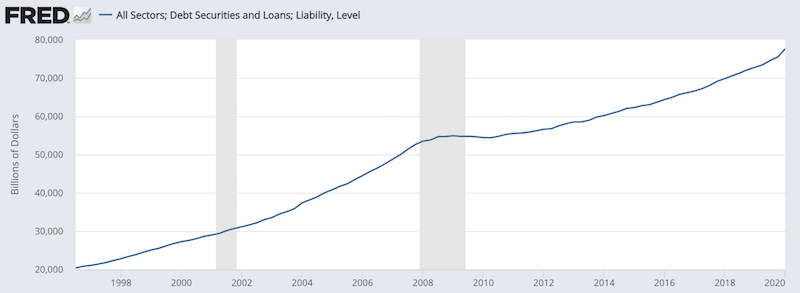

If we take the total amount of debt in circulation in the US, it’s around $80 trillion.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

These numbers also excludes various other forms of wealth, such as equities, warrants, property, collectibles, other tangible assets, and so on. There is also a substantial amount of dollar-denominated debt that exists outside of the US, which would further bloat the level of outstanding claims.

But using those limited debt numbers as a guide, the amount of promises to deliver money (i.e., using debt only) is about 16x the actual amount of money available to deliver to make due on those claims.

The general idea is that most people will create credit and future claims on income and won’t pay much attention to what the actual promises to deliver are and where they’re going to get it from. Accordingly, there is a lot less money than outstanding obligations to deliver it.

Moreover, the definition of money isn’t often clear, though it’s important to note. Money is what payments are settled with.

Money is not simply whatever buys goods and services, whether it’s cash or a promise to pay (i.e., credit). Both money and credit serve the same purpose as sources of spending power, but they’re very different.

When someone goes into a store and buys something with a credit card, they didn’t buy it with money. The transaction hasn’t been settled yet. It formed an IOU that’s a promise to pay money at a later date.

Central banks tend to define money in terms of various aggregates, such as M1, M2, and so on.

However, much of what’s included in those aggregate totals is credit (i.e., promises to pay) and not money itself, which makes these metrics misleading.

Financial securities and wealth

A financial asset is a securitization of a cash flow. Wealth is a claim on somebody else’s future income.

If you buy a bond, that’s a promise to deliver currency over time. If you buy a stock, that company has to generate a profit for it to produce an income stream over time and validate its valuation.

The discounted value of these expected future cash flows over time add up to give it its present value (i.e., its price).

Changes in the expectation of the future income stream are the primary mover of its price. Traders use various tactics to make money based on this price movement.

Wealth as a source of potential tax revenue has to be viewed in the context of:

a) How liquid is it?

b) How much income does it generate?

We can go through a whole host of assets that people might own to understand how a wealth tax might impact them:

Cash

Cash is liquid. If you’re in developed markets, it probably doesn’t generate any income, or could even have a negative interest rate attached to it.

Cash by itself is the easiest to tax. But if it doesn’t yield anything and/or the government wants to take a percentage of it, that incentivizes people to push it into other asset classes and bid up their values. Or else they will move it elsewhere outside the hand of tax authorities.

This weakens the currency. It also makes monetary policy harder to manage.

It is widely known among economists, traders, and other market participants that central banks face a trade-off between output and inflation when they change interest rates and the amount of money and credit in the financial system.

What is not as popularly known is that the trade-off between growth and inflation becomes harder to manage when money is leaving the country. Likewise, it becomes easier to manage when capital flows are positive.

This is because these positive capital inflows can be used to increase foreign exchange reserves, lower interest rates, and/or appreciate the currency, depending on how the monetary authorities chooses to use this advantage.

Bonds

Bonds are longer duration fiat currency flows. If you own a million dollars’ worth of US Treasury bonds, for example, they have the benefit of being liquid.

But like cash, they yield nothing or close to nothing. This makes them a poor source of income. Any additional tax on this type of asset class would push more investors out of it.

This would cause interest rates to raise and could also hit the value of riskier assets given interest rates feed into the calculation of the present value of cash flows.

The government could also exempt these types of securities, and those of local and state governments to preserve their value as a store of wealth and also to avoid the second-order effects of higher interest rates.

Having high demand for your credit is important for your status as a reserve currency. You can borrow more without running into balance of payments and inflation and/or depreciation issues.

Stocks

Stocks would be an obvious asset class to go after for proponents of wealth taxes.

Equities are liquid, as anyone can sell off their shares in the open market during the specified hours of the exchange on which it’s listed.

They also typically produce an income, through dividends. Some companies on the public markets, however, are not profitable, which means investors are discounting the expectation that it will produce an income in the future.

But such a tax would compress their valuations and undermine needed investment.

Moreover, many different groups of people in a country have exposure to the stock market. This means it doesn’t just hit wealthier individuals (though it would do so disproportionately), but working and middle class workers as well who have less disposable income.

Metals

Something like gold is somewhat liquid. It’s not as liquid as traditional financial asset markets (e.g., stocks, bonds), but it also depends on how it’s owned. In physical form, it’s the least liquid. The futures market is relatively liquid on a smaller scale. There are also gold ETFs that provide exposure to gold in a liquid way.

Gold is not chiefly relied on to generate income, but as a store of wealth and a reserve asset. The same holds true for silver, which is less liquid than gold.

Other commodities, like copper and so on, are often industrial feed-ins and sometimes used as sources of speculative activity by traders.

Collectibles

A painting on a wall, for example, could be notionally valued at $5 million.

But it most likely doesn’t generate any direct income and its value as an investment asset is tied to future price increases. It may also be hard to sell as the number of entities out there in the art market willing to purchase art at such a high price is inherently low. That makes it an asset that’s not particularly liquid.

And whether that’s its genuine value is speculative. An appraisal can be determined through numerous ways to triangulate its value.

For example, one can look at comparable sales in the market recently for the artist and/or other factors (e.g., size, time period, style, scarcity) and apply a valuation. One could also ascertain if the piece was recently sold and apply a valuation based on how valuations have gone up or down since the previous transfer of ownership.

But illiquid, non-income producing assets like collectibles are among the least efficient to collect tax revenues from.

Such taxes are especially punitive if the taxpayer has a high level of illiquid, non-income producing wealth relative to liquid wealth and income.

Real estate

You could own a piece of real estate valued at $2 million. But if the rent is $6,500 per month (your revenue) and total all-in monthly costs paid by the owner are $10,000 per month (principal, interest, HOA fees, property taxes, insurance, utilities), you’re taking a $3,500 per month loss taking the difference between the two.

That means the value of the property needs to appreciate by about 2 percent per year ($3,500 * 12 divided by $2 million) just to breakeven.

A home at that price point is not particularly liquid. And as a source of income, it’s not effective because it actually loses money.

If this house was your primary residence and you didn’t generate an income from it, then it would carry the double burden of being illiquid and having an even more negative income associated with it.

Real estate and land, of course, is already typically subject to a wealth tax on its own in the form of property taxes. Such taxes are already accounted for in their valuations, as part of the cost structure of owning property.

Digital currencies

Digital currencies and cryptocurrencies are subject to their own laws and regulations regarding taxation. As a fledging asset class, that’s still being determined as regulators learn more about it.

Most digital currencies are fairly liquid with the ability to buy and sell them easily on a dedicated exchange.

The profits associated with them are mostly from speculators who are successful betting on its directional price movement.

Some digital ‘coin’ holders more closely resemble investors. Namely, they view the nascent state of the market as a favorable factor or treat it in the same way they might view precious metals – i.e., bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as a store of wealth due to the lack of quality forward yields in traditional asset classes.

They nonetheless have a long way to go to become reserve assets that might be looked upon by central banks or sovereign wealth managers, or stores of wealth by the big institutional investors who will dictate their value.

The main thinking is that blockchain technology can help drive efficiency changes in corporate processes or in global payments systems.

Can they go beyond speculative instruments and help streamline operational processes, reduce costs, create value for customers, and adapt to the competitive pressures from incumbents and new entrants?

Robust governance, a comprehensive legal framework, and appropriate regulation will all be necessary to produce dependable and sound systems that can scale up to broader adoption in financial and non-financial contexts.

A wealth tax could be viewed as a negative for digital currencies, as a liquid asset class that nonetheless doesn’t produce income (outside speculators who bet correctly on price direction).

Private businesses

Private businesses are inherently illiquid. Getting access to liquidity through an IPO (or similar structure) is one of the high points of going public. Investors can finally sell their shares into the market.

They also may or may not produce income. Many startups that focus on growth and market share are not profitable.

Thus wealth taxes are an extremely poor fit in these cases as a way for governments to collect cash. They face the dual issues of being illiquid and not producing an income, or operating at a loss, which may mean future capital infusions.

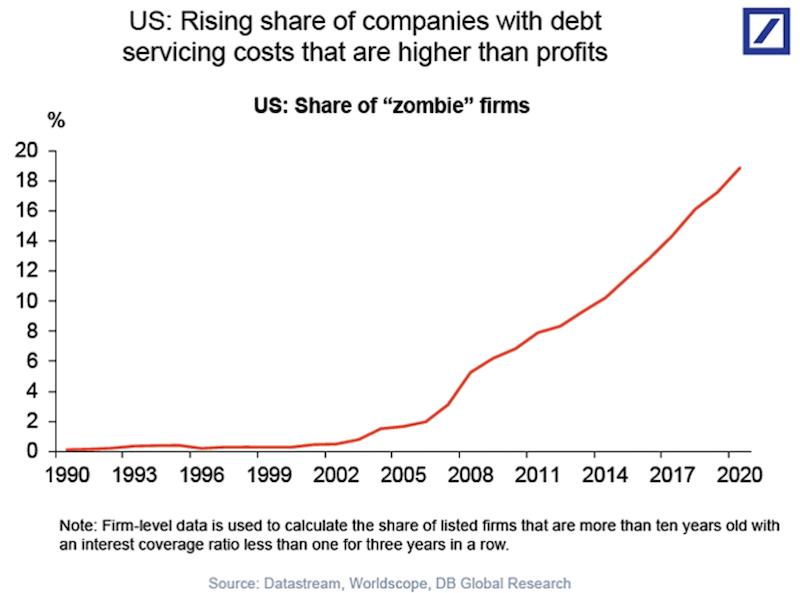

And because of very low interest rates throughout the developed world, many businesses have access to very cheap capital that allows them to keep going.

Close to 20 percent of all companies in the US are “zombies”. Namely, their earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) doesn’t cover their interest expense.

Many are not viable businesses but still retain value, sometimes very high values, due to judgments of what they could be (basically a call option on a certain conception of what the business might be at some point in the future).

This is also why the concept of net worth for people and businesses can be highly misleading.

If someone sells 5 percent of a business for $60 million and owns the other 95 percent, they may have a net worth on paper of over $1 billion. But that doesn’t provide any information about their actual level of liquid wealth or what kind of income they’re making.

If the company is at breakeven or less and the owner has no other material source of income or assets, then there is no liquidity available. A wealth tax would not make much sense as a way to tap revenues.

That “wealth” is just a paper claim on some uncertain amount of future income, and in no way relates to income or available liquidity in the present, and may or may not even materialize.

For any type of asset that relies on future income generation to validate its value, and “wealth” is simply a subjective calculation of the present value of future estimated cash flows, if that income doesn’t exist in the future, then that wealth doesn’t actually exist at all.

Whether the claim is in equity or credit form or some combination, if the future claim on income doesn’t materialize, then what the holders of it assume is an “asset” isn’t actually an asset at all.

Wealth tax and class divergences

Class divergences have historically gone hand in hand with the popularity of calls for wealth taxes.

Capitalism is now operating in a way in which people and companies find it most profitable to have policies and produce technologies that lessen their people costs.

This in turn reduces a large percentage of the population’s share of society’s resources and there is no plan to deal with it well.

The wealth, income, and opportunity gaps that manifest can lead to dangerous social and political divisions.

The companies and individuals who are richer have greater buying power, so this motivates businesses and profit-seekers to shift their resources to produce what more well-off people want relative to what the “have-nots” want, which includes fundamentally required things like good care and education for children from less well-off families.

This can lead to harmful and self-reinforcing deprivations for those at the bottom.

Budgets vs. ROI

Policymakers focus too much attention on budgets relative to returns on investments.

For example, not spending money on educating and taking care of children well might seem good from a budget perspective, but it’s really bad from an investment perspective.

Looking at funding through the lens of a budget doesn’t lead policymakers to take into consideration the all-in economic picture – e.g., the all-in costs to society of having poorly educated people.

For example, take the concept of childcare. It’s another one of those things in the US that’s largely left to the private sector or local governments.

For childcare, parents either:

- pay a private babysitter

- “pay” through lost income doing childcare themselves

- have it subsidized through maternal or paternal care through the company they work for, or

- take advantage of state and locally funded programs

A lot of decisions are deferred to local/state governments and not directly handled at the federal level.

One could argue that the social safety net isn’t adequate in the US, especially for children. Too many children grow up in poverty in the US (17.5 percent) and not educating them well without adequate public school funding is not good economically.

It brings about painful and counterproductive domestic conflict and undermines the US’ strength relative to global competitors.

While focusing on the budget is what fiscal conservatives typically do, fiscal liberals have typically shown themselves to borrow too much and fail to spend it wisely to produce the economic returns required to service the debts they’ve taken on. So they often end up with debt crises

The budget-conscious political right and the pro-spending/borrowing political left have trouble focusing on and working together to achieve quality return on investments that produce both good social returns and good economic returns.

Limitations and trade-offs

Politicians don’t like to face limitations and trade-offs because it’s not politically popular to do so.

There’s lots of talk nowadays about how you can print money and create debt with no consequences, but it’s not true. No entity can spend beyond its means forever.

And policymakers are only there for a short period of time; no one person owns the entire cycle. So they can pass off a progressively indebted situation to the next set of people.

The dollar’s reserve status is being taken for granted.

Eventually, spending has to get in line with income, which is a function of productivity.

That means eventually there’ll be a devaluation in the dollar until there’s a new balance of payments equilibrium, meaning forced selling of real and financial assets and curtailed buying of them to the point where they can be paid for with less debt.

Loss of reserve status essentially means forced budget controls, which you eventually get one way or another.

If you continue to get spending in excess of income, then more currency depreciation and monetary inflation will be the result.

Final Thoughts

The purpose of this article isn’t to opine on whether wealth taxes are a good idea or a bad idea. Like many things, there is no black-and-white answer, as they can take an infinite number of forms in their scope and size.

Some forms of wealth taxes, like property tax, have been well established and are common globally. Inheritance taxes are another form.

But in this period of high spending, rising liabilities, and higher levels of inequality, governments will continue to seek out ways to raise more taxes. They need the income. They will have issues cutting spending and governments have varying levels in which they can print money to monetize liabilities.

And policymakers will have to find a way of taking in more tax revenue without undermining productivity.

In political movements in all developed market countries, there have been calls by many politicians to raise taxes significantly on the wealthy. Much of them will target income and consumption, as they’re the most effective in raising revenues by tapping tangible forms of liquidity.

Some will call for higher wealth and inheritance taxes. But these, even if implemented, will generally raise relatively little money because much of what we call wealth is illiquid.

Even for assets that are liquid, forcing the taxpayer to sell financial assets to make their tax payments depresses the values of these assets, hits taxpayers downstream (i.e., the working classes with retirement and/or personally managed accounts), and undermines capital formation.

Moreover, calls for significant tax hikes usually come during times of broader economic weakness (e.g., 1930, 2008). This means both earned incomes and the incomes derived from capital are typically depressed and expenditures on consumption are down.

Those who are targeted for their wealth typically become defensive and increasingly want to move their money and assets out of the country, which contributes to currency weakness, and seek safety in liquid assets that are not credit dependent (e.g., gold, precious metals, other tangible assets).

Calls for wealth taxes tend to coincide with higher levels of social tensions

Wealth taxes tend to be popular during periods when there is economic weakness, higher levels of inequality, social tensions between the “capitalists” and “socialists”, and greater political polarity.

Applied excessively or on illiquid forms of wealth, these taxes can undermine productivity. This shrinks the total amount of wealth in a society and create greater conflict on how to divide up available resources. In turn, this leads to even more conflict, which leads to political infighting between opposing leaders who want to take control of the situation to bring about order.

During these times, democracy is challenged more by autocracy.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Germany, Japan, Italy, Spain, and many other smaller countries turned away from democracy and toward more autocratic forms of leadership.

The three major democracies (the US, UK, and France) all became more autocratic as well.

We’ve also seen more unruly, violent social behavior with a reduced respect for law as a result of various issues bubbling to the surface.

During periods of greater chaos, more individuals believe that more centralized and autocratic decision making (i.e., less political compromise) is more suitable than less centralized and more democratic decision making. The belief is not without merit depending on the quality of the decision making; like any system there are pros and cons.

Three big influences

Broader picture, there are three big forces that are converging that haven’t been seen since the 1930s:

– the degree to which the various “gaps” exist (wealth inequality creating friction, values gap, ideology and political gaps)

– limited ability for central banks to stimulate the economy (same thing after the 1929 debt bust in the US and most of the developed world)

– and a rising world power in China coming up to challenge the US, the incumbent power (similar to Japan and Germany in the 1930s)

You have the usual matters playing out with respect to trade conflicts, the threat of capital flow disruption, separate technology development (e.g., 5G, quantum computing, artificial intelligence chips, information and data management), brewing conflict on global spheres of influence (e.g., China’s role in the South China Sea and influence over Taiwan and Hong Kong).

From here it’s most likely to become geopolitical in most other ways. The US can unilaterally cut off capital flows to China, impose sanctions on non-US financial transactions with China, freeze payments on debts owed to China, and so forth.

More countries are having to choose whether they’re aligned with China or with the US.

There’s an economic component (more countries are aligning with China) and a military component (most still sided with the US).

Will the world peacefully evolve to have two spheres of influence or will there be a more direct confrontation down the line?

Tax impacts

Forms of taxation (individual and corporate rates) are another piece of the puzzle in how they’re currently influencing financial markets. Taxes are a matter of importance in the way they impact valuations in various asset classes and certain players within those markets.

For these matters, traders will look toward election probabilities in the case where major elections are upcoming. They will look at the likelihood that various proposed tax plans will be implemented. This will depend on the stated intentions of candidates, the veracity of their claims, and the likelihood of constituents going along with their proposals.

Wealth taxes are a more aggressive approach that commonly bubble up in periods with similar conditions to what we see currently.