The Internal War: Conflicts Within Countries & Impacts on Markets

How people act with each other is the most important determinant of domestic conditions. The internal war is ultimately the most consequential type of conflict the US and other countries face.

Even with the importance of US-China relations and its impact on the markets – via trade, economics, capital and currency, technology, geopolitical, and military armament and potentially a hot war in some fashion – the internal war is more influential to the future of individual countries.

As a result, we’re including the internal war among our list of the major conflicts, the first five being external (with a focus on US-China) and the last domestic:

i) trade and economic

ii) capital (currency, debt, capital markets)

iii) technology

iv) geopolitical

v) military

vi) internal/domestic

The EU Example

The US gets more attention geopolitically because of its status as the world’s largest economy, the outsized role of the US dollar, and because of its military strength. Its internal strife has gotten a lot of attention globally.

However, the EU suffers from a lack of social unity as well.

It’s been believed by some traders and investors that the EU (and developed Europe more broadly) would be the most strained of all developed market economies whenever there’s an economic downturn (i.e., between itself, the US, and Japan).

Part of this is the reality that the EU doesn’t have unity within countries or between countries.

Its way of operating also tends to reinforce this.

For example, the EU doesn’t have a common fiscal policy. That means monetary policy is the main channel to fight an economic slowdown.

But because so many countries are on the euro, the pegged currency system interferes with the ability for most members of the bloc to pursue an independent monetary policy – i.e., to balance output and price stability in light of their own conditions.

This leaves the currency too weak for a relative high-performer like Germany and too strong for the perpetually under-performing periphery countries.

This contributes to disparate growth outcomes and more social conflict. This flows over into political movements. For example, populism is more popular in Italy than the rest of the EU because of this.

With the monetary and fiscal constraints of the region, to go along with the disparate social elements that are only reinforced through this flexibility, the EU would probably be the most strained of the developed economies.

Countries’ biggest conflicts are with themselves

The greatest conflict countries have is with themselves. For the United States, it’s not China that primarily holds the keys to its future, but the US itself.

Each country determines how strong or weak it will ultimately be based on what it has to work with.

While some things represent obstacles in some form – e.g., population size, geographic barriers, relative resource richness or scarcity – ultimately people within countries determine how strong or weak they become.

In a previous article we laid out a set of factors that determine how well an empire maximizes its potential in terms of what kind of power it can have and the living standards it generates for its people.

These include the following and tend to feed off each other, as they interlink and reinforce other elements:

1) Having strong and capable leadership.

2) A strong education that teaches not only skills but develops character and promotes civility.

3) Developing and reinforcing strong character, work ethic, and civility throughout the population.

4) Strong and equitable rule of law, high respect for rules, and low levels of corruption.

5) Having a united mission that everyone can get behind where people have the skills, abilities, character, and civility to work well together.

6) A quality system for efficiently allocating capital and labor.

7) Being open to the best thinking possible regardless of where it comes from, whether it’s outside technology or ways of operating.

8) Cost competitiveness globally to help bring in more revenue than expenses going out.

9) Income growth and having incomes rise in line with productivity growth and in line or faster than debt growth.

10) Debt investments in education, infrastructure, and R&D produce more in productivity benefits than they cost.

11) Increased productivity helps produce greater wealth-generation capabilities and increased production of new technologies.

12) New technologies aid commerce and military improvements, and overall national competitiveness.

13) Trade and capital flows are positive, as others want to invest in the country and have what it’s producing and offers to the world.

14) Trade routes require a strong military, which also helps influence others outside of their own main territory.

15) Having a large share of global trade also helps develop the usage and desire for its currency.

16) A pervasively used currency as a medium of exchange and store of value (i.e., a reserve currency) helps develop its debt and equity markets.

17) This, in turn, helps develop a leading financial center in the world for both attracting and allocating capital. For example, what Amsterdam was to the Dutch empire, London to the British empire, New York to the American empire, and what Shanghai is likely to represent to the modern Chinese empire.

All of these help reinforce the other.

If one isn’t as strong as it can be, it takes away from other links in the chain.

Making improvements in each helps empires to obtain, expand, and sustain the power they have.

Internal Civility is not Just Enforcement

Civility is also not just having a stronger police force.

It’s a way of behaving or code of ethics that’s internal within the people so it doesn’t produce the problems in the first place.

Success feeding the decline

In markets, it’s commonly known that a bull market that proceeds in a fairly orderly way causes more people to leverage up in a way that extrapolates the past.

That tends to sow the seeds of its own demise as the leverage buildup going into a period where forward returns are lower is essentially the opposite of what makes good sense. Naturally, it tends to exacerbate shocks back in the other direction.

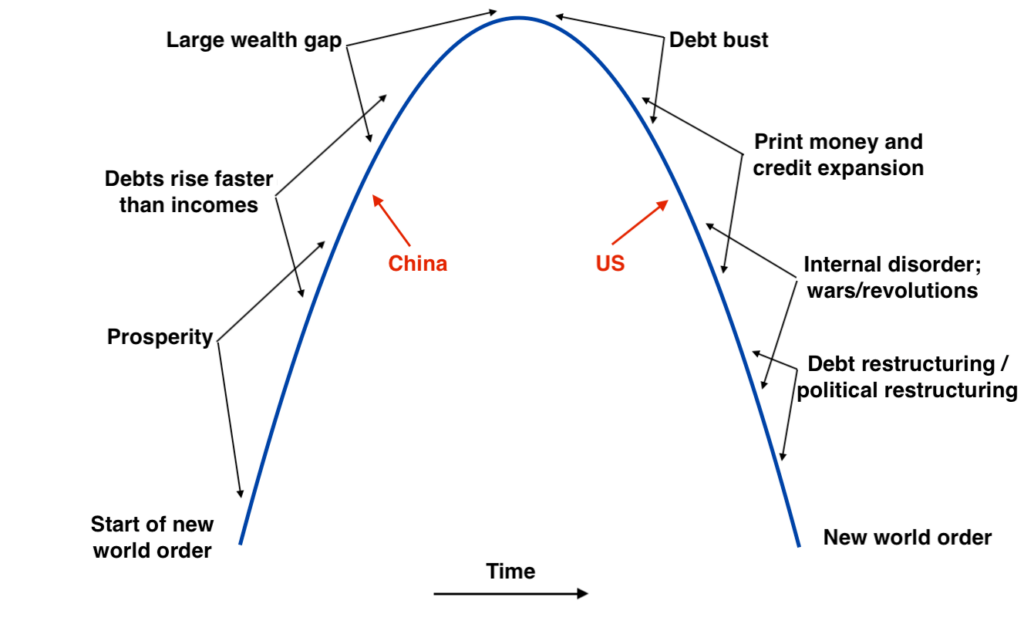

In the case of empires, and in the case of assessing the merits of investing in a country (its assets and currency), you have the classic signs of an empire’s previous success sowing the seeds of the decline, which also proceeds in a cyclical way.

As countries become wealthier, they tend to become less competitive because being successful means emerging competitors will want to copy what they’re doing. (This is what China has done with respect to the US in various ways, for example.)

Moreover, more overall wealth among a population typically means more time is going to be spent on “savoring life” and pursuits that are separate from productive activities like working, saving, and investing.

Earlier generations that were more financially cautious and had to work hard to achieve success eventually pass on and newer generations become a majority who are more inclined to take more leisurely pursuits.

Being wealthy, powerful, and global also means having a reserve currency. This is a tremendous privilege because it allows countries to borrow more money and spend beyond their means.

This boosts spending power in the short-term. And this is often reinforced, which creates even more borrowing, because policymakers’ timelines normally run on a short-term time horizon. But it weakens a country over the long-run.

While spending and borrowing a lot makes an empire look strong – typically to finance over-consumption and military and wars to sustain its empire – its finances are fundamentally deteriorating.

There is currently a lot of talk about how a lot of debt and money can be produced to spend more without suffering bad consequences, but it’s not true.

The excessive borrowing can go on for quite a while and even strengthen the currency in the short-term.

The reckoning comes eventually

When the need to pay back debt comes, and there’s the trade-off between taking it through incomes (living standards) or devaluing money (more discreet and usually less sharp, but also a lowering of living standards), people suffer.

This worsens the social and political conflicts. And the cycle generally ends in some form of painful debt and political restructuring.

People may look at the national debt figure and the other liabilities related to pensions, healthcare, and other unfunded obligations, and it doesn’t seem consequential now.

But the future and the “long term” eventually becomes the present and countries/empires face a reckoning over the situations they’ve led themselves into.

In the US, we are facing circumstances that will leave us with a very ugly set of trade-offs down the line and a small range of options relative to if long-term health had been more prioritized.

On the back side of the prosperity cycle

The US has largely had a prosperous and enjoyable period since the end of World War II. The country has been fundamentally strong because of:

- relatively low levels of indebtedness

- relatively small wealth gaps, values, and political gaps

- people working effectively together to produce prosperity

- good education and infrastructure

- strong and capable leadership, and

- a peaceful world order that’s been guided by one or more dominant world powers

But prosperous and enjoyable periods are always taken to excess, which they have been in the US.

The excesses lead to depressing periods of destruction and/or restructuring in which the country’s fundamental weaknesses of:

- high levels of indebtedness

- large wealth gaps, values, and political gaps

- different factions of people unable to work well together

- declining competitiveness and infrastructure, and

- the struggle to maintain an overextended empire under the challenge of emerging rivals…

…which lead to a painful period of fighting, destruction, and then a restructuring that establishes a new order, setting the stage for a new period of building.

Nothing lasts eternally

No system of government, no economic system, no currency, and no empire lasts forever. Yet almost everyone is shocked and badly hit when they fail.

The rich borrowing from the poor

When the richest countries start borrowing from the poorest, it’s typically a sign that a relative wealth shift is starting.

In the 1980s, China started saving in the US dollar – when the US’s per-capita income was still around 50x that of China’s. The Chinese did so because it was the world’s top reserve currency.

The British empire engaged in the same type of borrowing from its poorer colonies, notably during World War II, and the Dutch empire did so before that in the 1600s.

This activity preceded the tops in their currencies, economies, and the overall relative standing of their empires before the demand for their money and debt fell.

Getting deeper in debt to foreigners helps sustain their economic and overall power beyond their fundamentals.

Because of the excessive borrowing and debt-financed spending on goods, services, and financial assets, bubbles are common. These also tend to develop large wealth gaps. This is because those who own the most financial assets tend to benefit from them most.

Social conflict

When there’s an economic downturn and there are large wealth gaps, there is more social conflict between the various factions. The poor want more money from the rich. There are larger values and ideological gaps as well.

This bleeds into what types of leaders are chosen and tends to be self-reinforcing as more extreme candidates force more moderate candidates to be pulled left or right to avoid being unseated.

When this occurs, it widens the range of policy outcomes and could create more volatility in markets when the outcomes for tax policy, regulation, trade policy, and other matters have a wider range of possibilities.

Early in the cycle, there’s more spending of money and time on productive things. Later in the cycle, more money and time go toward indulgences.

In the “bubble prosperity phase” – which the US is still in, but going into a period of worsening financial conditions and greater conflict – there’s a lot of spending by the “haves” on expensive homes, jewelry, art, fashion items, etc. And it’s considered fashionable and admirable to buy and own these things.

But that starts to shift when you move into the next phase of bad financial conditions and more intense conflict. And often that spending is financed by debt, which worsens overall conditions.

The “haves” feel like they earned their money and can spend it on any luxuries they’d like, while the “have-nots” view such spending as selfish and unfair given their hardships.

Outside of the class resentments, such indulgent spending reduces productivity, as it’s distinct from saving and investing.

Given where the US and China are in their respective development arcs, you could probably expect more growth in luxury spending in China, as it develops new middle and upper classes, and less so in the US.

What a society spends on matters a lot. When it yields broad-based productivity and income gains that exceed the borrowing costs it makes for better living standards and a better future, as opposed to consumption items and inefficient spending that doesn’t raise overall productivity and incomes.

Increased political extremism and hollowing out

There is both populism of the left and populism of the right when classes diverge and social conflicts grow.

When this occurs, the wealthy fear they will be treated unfavorably and feel like a large and/or growing portion of their money and/or assets will be taken from them.

As a result, they increasingly want to move their money, assets, and/or themselves into currencies, assets, and/or places they believe will be safer.

This reduces that country’s or jurisdiction’s tax revenue relative to its spending requirements. That creates larger deficits, which typically means higher tax rates.

This, in turn, tends to exacerbate the problem as those who are being taxed the most are more motivated to leave. They also tend to be the people who spend the most and provide jobs, which creates the incomes for other workers and tax revenues they pay to local and national governments.

This means less spending on the basics, which worsens conditions, and further raises tensions and calls for higher tax rates and larger deficits, and more hollowing out.

Divisions around elections

These divisions in the US – i.e., between the left and the right, the rich and the poor, urban/rural, ethnic groups, etc. – are likely to heat up again before the next presidential election.

There’s also a reasonable chance that neither party will accept losing that election, just like in previous years.

If that were to happen, rule of law and the constitution will be less influential than raw power.

New monetary and fiscal policy paradigms

When there’s a very large debt accumulation and the central bank (or central monetary authority) has pushed down interest rates as far as they’ll go to stimulate debt growth, it has lost its ability to push credit into the economy in the normal ways.

Normally, whenever interest rates are lowered, there’s additional demand that “comes off the sidelines”.

It works in three main ways by:

a) stimulating extra demand for credit,

b) making debts easier to pay because lower interest rates reduce total interest costs, and

c) increasing the value of financial assets through the present value effect.

When interest rates hit zero (or a bit below zero) at the front end of the yield curve, and later in terms of longer term borrowing rates, that’s an indication that private sector credit creation is approaching its constraints.

That’s when monetary policy and fiscal policy must coordinate together to get money and credit into the system. The central bank creates the money and the fiscal arm of the government must distribute it to where it’s needed.

While the adjustment of interest rates (monetary policy) tends to be more democratic in scope, fiscal policy will pick more winners and losers, as it depends on politics.

So, traders will need to ask themselves what kind of companies are likely to get this support.

Are companies that have high strategic importance likely to be among the top beneficiaries (e.g., production of defense systems)? Are companies that focus on the production of cleaner energies in this type of bucket? How might a coal company do?

In general, what companies is this money and credit hitting and which ones is it missing?

At the same time, when there’s an economic downturn and monetary policy is ineffective and there’s a battle over what to do fiscally, that produces more internal conflict over money and wealth.

And because it produces more central bank money creation, it devalues it.

The basic causes of these problems stem from the fact that the costs of maintaining the empire and defending it militarily are in excess of the revenue it takes in. It’s uneconomical.

So, essentially the government operates at a perpetual loss and must fill in this loss by selling debt. This weakens the country financially and its power globally also declines.

Disruptive conditions undermine the country’s productivity. Then there’s more conflict on how to appropriately divide up the shrinking resources.

A rising competitive country often gains more economically, technologically, geopolitically, and militarily during the incumbent’s period of weakness to effectively win new markets and gain new influence over territories.

Other exogenous shocks, such as plagues and natural disasters, may occur during times of weakness and, if they do happen, hasten the downward spiral.

General Market Playbook

The mix of economic, social, and political factors producing the conflict can be observed in the backdrop of financial markets.

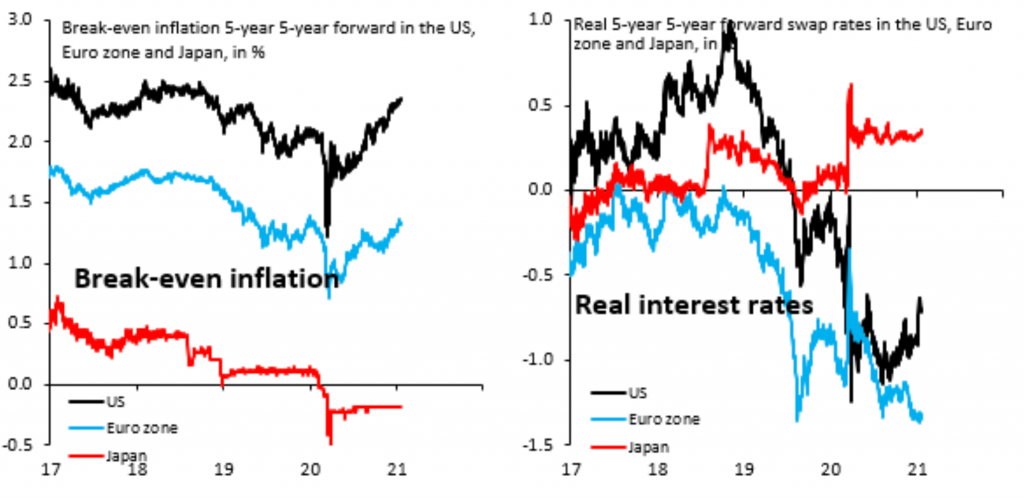

Because of the sheer amount of debt creation and money printing to fill in for various liability and income gaps, that’s produced negative real interest rates.

That creates its own host of problems because people want to get out of cash and debt when it doesn’t yield anything and more of it is being created.

Then it’s a matter of what are those other alternatives:

a) Commodities and other alternative currencies

b) Different countries (i.e., a form of capital flight)

c) Different types of bonds (e.g., inflation-linked instead of nominal)

d) Certain types of stocks

e) Private assets and going outside traditional liquid markets

The basic backdrop: Negative real interest rates

The US and developed Europe have negative real interest rates based on their five-year sovereign debt maturities. Japan is slightly positive because it has a problem getting inflation up to zero.

As mentioned, this is the type of environment where cash and bonds are not attractive because they’re creating a lot of it to contend with bloated debt and non-debt liabilities (e.g., related to pensions, healthcare, other unfunded obligations) and the yields on these instruments are so low.

When this is the case, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to hold a lot of cash and bonds, as real spending power erodes storing your wealth in them.

That forces more market participants into stocks and other assets.

Commodities and precious metals

Holding all else equal, commodities, gold, and other types of alternative currencies become more attractive.

While things like gold, silver, and other precious metals don’t have an explicit yield to them (technically their yields are negative because of storage and insurance costs), their demand picks up when traditional financial stores of wealth (cash, bonds) see their real returns decline.

Geographic diversification

Geographic diversification will become more important.

Traders naturally have to be concerned about the implications of developed markets’ dependence on negative real interest rates to prop up their economies and markets.

There are three main implications:

i) a low discount rate on earnings (meaning bonds, credit, and equities go to sky-high levels and become riskier)

ii) bonds provide little risk diversification when their yields are so low

iii) a weak currency

While real yields are a fixture of developed markets, in developing Asian economies (in particular) they have a normal interest rate on cash and a positive-sloping yield curve.

To go along with what “printing” money does for a currency (devalues it over time), more capital will shift from West to East.

This is not only China because there are a number of other countries in the East where the market environment is different from that seen in Western countries.

Eastern countries didn’t have to balloon their deficits in response to the virus, as the US and other Western countries did by trying to keep people home as part of the distancing process and send income replacement support to the individuals and businesses who needed it.

Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

More people will want to own inflation-linked bonds.

While nominal bonds can’t go much below zero, because at a point doing so does little to incentivize additional credit creation, there is no limit to how negative real yields can go.

Real yields are equal to nominal yields minus inflation. That means the “price cap” or “yield floor” on nominal bonds doesn’t really apply to inflation-linked bonds.

So, the upward potential price trajectory of ILBs is not as constrained.

Companies with stable or growing earnings and those with strategic importance

__

Bond alternatives

Companies with stable cash flow are naturally being thought of as a type of bond proxy.

For many individual investors, and institutions like pensions, having a fixed income alternative is their main focus.

They want the yield but don’t want to take on a lot of risk.

For example, an individual investor might have $1 million saved up for retirement and be perfectly content getting five percent annual returns on that.

That would give them an income of $50,000 per year, which would fund a reasonable lifestyle most places and would enable them to not have to touch the principal.

If they earn more than that, that’s great but not important.

This means individual investors with an income generation focus, pensions, endowments, and similar entities are going to look for safer types of equities given they can no longer get this five percent yield out of fixed income markets in a safe way.

Certain stocks that involve selling products people need to physically live (e.g., food and the basics) can be good stores of wealth.

These companies don’t rely on interest rate cuts to help offset a loss in income and will always be in demand. While it may not necessarily be the same companies that succeed over time, but a diversified mix of consumer staples is likely to do well.

These might include companies like, for example, Coca-Cola, Proctor & Gamble, PepsiCo, Costco, Wal-Mart, and others that sell food and everyday items.

They won’t have the big ups and downs like companies that are interest-rate sensitive or highly tied to how the economy does, like a manufacturing business.

Market participants can feel pretty good about the idea, that out of the entire universe of public equities, that these types of companies are going to see their earnings increase fairly reliably at about the rate of nominal growth.

Some might consider utilities and real estate to be in the same boat given basic services (e.g., water, electricity, heating) and shelter are basic needs.

But these businesses tend to have a lot of debt, meaning interest rates matter to their valuations, which are largely outside of their control.

The type of real estate also matters. People don’t necessarily have to go to malls with so much commerce now done online.

“Innovators”

Certain technology companies are in this “store of wealth” boat as well.

Companies involved in the creation of technology that’ll drive the big productivity gains going forward can serve the same type of purpose in a portfolio.

Companies with strategic importance

Companies that are strategically involved in the creation of defense systems, aerospace, telecommunications equipment, and overall military capabilities are also likely to have increased importance.

Private assets

People will also increasingly turn to the private markets.

Having a liquid portfolio has a big host of advantages, such as being able to change your mind quickly and not being stuck with an asset if the reasons behind owning it have changed.

Owning a stock carries the advantage of being a passive investment. You own a portion of a business without needing to manage it.

But the lack of easy liquidity and, in many cases, the need to actively manage investments in the private markets will be worth it for some when the prospective returns are higher.

Going back to foundations

While China describes itself as “communist”, as do other countries, the style of “communism” and “socialism” is very different depending on where you go.

In places like Venezuela, Cuba, and other situations historically, it’s generally a system where resources are allocated very inefficiently. This generally results in little productive output because the incentives aren’t well-aligned between output and rewards.

In China, the communism they talk about is not like the old Maoist system.

The riddle people have to ask themselves is how can China be communist when they have the second-largest economy and second-largest capital markets globally?

They have a lot of state-run companies, but the overall level of “capitalism” is about the same as in the US. Their tax rates are lower, for example.

The current economic model is more like a top-down society run in a similar way to how a private company might be operated. There are people at the top and then everyone beneath them knowing their role and carrying it out in the interests of the whole.

Bottom-up vs. Top-down

The US is more bottom-up, which comes from its history of being a country of immigrants that came from all over. So the role of the individual is prized.

The cultural differences of the US vs. China are very real and it manifests in many aspects of our ways of doing things and conducting ourselves. It’s a big part of the current geopolitical divide.

It also points to the fundamental difference in citizen expectations of their government as well as expectations of the individual.

Risks to the system

In the individualist, democratic system, the main risk is people putting what they want above the interests of the whole, putting the whole system in jeopardy where you can have a revolution or civil war.

Democracy isn’t forever. Autocratic governments are more likely to form when there is lots of division and there’s more need to get control over the situation.

China has its own risks if the decision-making isn’t done well and the government is forced to evolve or is overthrown.

Dialectical materialism

The Chinese system is based on “dialectical materialism” – with modern roots in the teachings of Lenin and Marx. Their main focus is on growing the pie and dividing it well.

The Chinese are more strategic. Americans are more tactical.

Chinese think over longer time horizons because their history is longer and they study it more. Americans jump around much more – e.g., changing the composition of Congress every two years and changing presidents every 4-8 years – and think more short-term.

There are pros and cons to each system. But each will side will run the country according to what they think is best for them and neither will change for the other.

Conclusion

In our series on US-China relations and its prospective impact on the world and markets, we went through the various types of conflicts that the US and China are currently mired in and will be for a while, including:

– economics and trade

– currency and capital

– technology

– geopolitical

– military armament

However, the internal conflicts and challenges that the US, China, and other countries face are ultimately bigger and more instrumental than the head-to-head clash between countries.

This includes the partisanship and leadership at the local, state, and national levels. There’s the fragmentation and the question of whether leadership is skillful to navigate all the challenges ahead.

There are the various constituents and diverse elements that all have their own interests, and some that they’re willing to fight for.

There are larger than normal divisions between the left and the right, the so-called haves and have-nots, and other factions.

The most important matters are within each country’s control. And countries can also establish metrics that measure those benefits in relation to the costs to ensure that we’re rowing in the right direction.

In the end, what we get is largely the product of our choices.