SPAC Meaning: What Are ‘Blank Check’ Companies?

What does the SPAC acronym mean? SPAC is short for a Special Purpose Acquisition Company, also known as a “blank check” company. Here we explain the analytics and meaning of SPAC in investing terms.

A SPAC is essentially large pool of cash, which is listed on a public exchange with the sole purpose of completing an acquisition. It’s essentially a form of a backdoor IPO.

SPACs are unique in that they have no pre-existing business operations or even a particular target company in mind to acquire. If they do have a target firm they’re looking to acquire, they won’t identify what it is.

Investors in the IPO are not aware of what company they’ll be investing in. They’ll typically make a determination of whether to invest in the SPAC based on their trust in the particular investor/entity seeking to make the acquisition.

So, naturally, SPACs tend to be headed by popular investors such as activist investor William Ackman or former Citigroup banker Michael Klein.

SPAC Trusts

SPAC funds are placed in a trust account and will typically bear interest. The interest accumulated will normally be returned to investors at some point or be used to help fund the operations of the target company.

The blank check structure is not a new concept, having gone back to at least the 1980s. Back then, they were commonly populated by lower-quality or even fraudulent companies.

These days, they are often backed by white shoe investment banks, including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan, and other prominent investors, and listed on leading exchanges like the NYSE or NASDAQ. Goldman underwrote its first SPAC IPO in 2016.

They are traditionally popular in the TMT space (technology, media, and telecommunications), healthcare, and retail.

Target Acquisition Using A SPAC

Many prominent investors have used blank check vehicles with the open-ended goal of acquiring a target. Pershing Square Tontine Holdings is set to be a $3 billion IPO, the largest SPAC ever.

With additional funding, it could have up to $6.5 billion. This could potentially involve an IPO of a private firm worth north of $10 billion.

These blank check vehicles have no operating history when they go public. They are contractually mandated, usually within two years, to use the proceeds of the IPO to acquire or merge with a target company. If they don’t, the funds must be returned to the public.

We’re also in an environment where there’s a lot of liquidity from central banks propping up the economy. Naturally, this bids up asset prices.

When there’s a lack of compelling forward returns in traditional asset classes, investors increasingly go searching for alternatives wherever they can.

This is helping to popularize the SPAC structure. Governance of the blank check structure is also regulated lightly and major investment banks have used the structure to help investors access capital financing.

New SPAC listing totaled over $12 billion in the first half of 2020. The debut of Pershing Square’s SPAC will break 2019’s annual record of $13.5 billion.

Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic Holdings (SPCE), a space tourism venture, went public via a SPAC.

Online gaming is also a popular blank check vertical, with DraftKings and Golden Nugget Online Gaming going public via the structure. Twenty companies went public via SPACs in the first half of 2020 with their aggregate market valuations totaling some $45 billion.

SPAC Risks

A SPAC boils down to an abbreviated IPO process with fewer disclosures. This subjects blank check companies to less scrutiny, creating potential risks for investors who have less information on which to base their decisions.

In some cases, SPAC investors often take a large amount of the equity in the business they acquire, often upwards of 20 percent, even if the target company sees its value dip once public.

In others, the SPAC and target company will better align incentives between them, allowing the SPAC to buy shares if the firm rallies by a certain percentage.

This incentivizes investors to only go after the best possible targets and not simply invest in anything that would effectively guarantee a return in some form. This arrangement also ensures that the target firm has a “true partner” backing them.

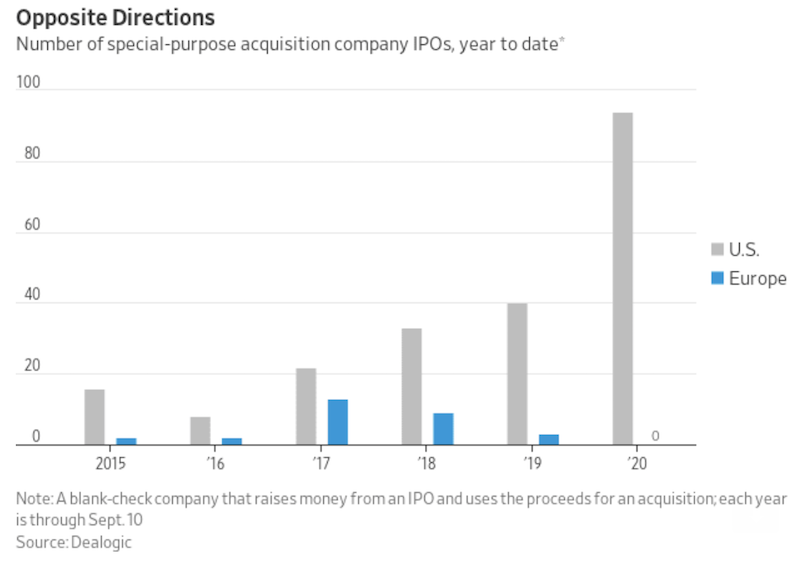

Differences Between The US And European Markets

Every company obviously wants their IPO to be a success to obtain the best value for any shares they release to the public.

If the general environment is bad, then companies are more inclined to stay private or will seek out alternative arrangements, like SPACs.

In major European hubs like London, the blank check structure is uncommon and Europe didn’t benefit from the activity as they did in the US.

As a result, European exchanges are looking for ways to ignite more interest in these offerings where investors can vote on an acquisition target from the pool of collected funds.

Investors in SPACs in the US vote on the acquisition and redeem their money if they don’t like the deal. However, in the UK, investors are not permitted to trade a SPAC’s shares from the time a deal is announced to approval of the prospectus.

That means investors can be tied into an acquisition they don’t approve for an extended period of time. The difference in these rules accounts for the relative attractiveness in the US SPAC market versus the tepid European one.

SPACs – A Fad And/Or Bubble?

Bubbles always look obvious in retrospect but it’s not always clear they are one in the present. Even when something doesn’t have a clear rationale for why it’s valued the way it is, prices get where they are for a reason.

It’s simply a function of the money and credit spent on something divided by its quantity. Valuation isn’t the only thing that motivates that process.

Bitcoin didn’t (and doesn’t) fit the two main characteristics of a currency – a medium of exchange and a store of wealth – but some viewed it as “the future” or something they wanted to speculate on.

The dot-com stocks were extremely overvalued to the point where it took the NASDAQ nearly 16 years to recover after it crashed. But at the time the belief is that they were going to dramatically transform the economy.

The same was true of railroads, canals, and new innovations from previous centuries.

With bubbles, the speculation on the extent of the disruption goes beyond what these new developments will justify in terms of actual economic earnings.

This goes for all “new age” verticals that have undergone bubbles recently.

“Alternative harvest” companies are still producing a crop. Electric vehicles are still in the capital-intensive, thin margin auto manufacturing industry. Blockchain’s efficiency enhancements remain speculative.

Investors become excited about something new, but earnings still need to be commensurate to justify whatever valuations become.

We’ve seen major bubbles develop…

SPACs

In typical bubbles, the hope and belief in future profit feeds on itself as prices rise. Investors fork over capital for investments they wouldn’t consider in more normal periods.

The South Sea bubble of 1720 was similar in that investors thought they were getting something great through a unique scheme between the government and private sector to reduce the national debt. It was granted a monopoly seven years prior to its bubble peak and subsequent collapse.

In a similar vein, a SPAC today involves investors handing over capital for an IPO of a yet-to-be-known entity.

But SPACs still come with protections and are not totally about blind faith in the way the initial SPAC wave of the 1980s were or the cash shell vehicles as they’re utilized under existing law in other countries.

The standard SPAC structure gives investors a vote in any deal they’re apart of. They also get the option to get their money back if they don’t like the deal under consideration, or if the deadline passes without a deal (usually the two-year window). Almost all of the money is held in escrow.

Unscrupulous stock promoters can’t simply take the money as they might with a blind pool of funds, similar to 1720. Moreover, they can’t commence a deal without getting their investors onboard.

Zero interest rates help explain some of the popularity of SPACs. In a normal environment where nominal rates are positive and real rates aren’t negative, you can let cash sit and make money safely.

Now, it doesn’t make anything and its real spending power erodes.

In other words, the opportunity cost associated with a SPAC is low. SPACs don’t make you anything at first, but neither do cash or a lot of bonds.

And SPACs have more upside from the valuation increase that typically occurs when going from private to public due to the liquidity and initial pop from public demand.

Holding everything else the same, there should be more demand for SPACs.

The essential purpose, of course, is that they are a simpler alternative to an IPO for private companies to list. There is less paperwork, less price uncertainty of an initial listing, and generally a more expeditious listing.

A SPAC is not cheap. Most managers running them get equity in the company worth up to 20 percent of the cash raised in the deal. But there is a level of convenience over a traditional IPO that may make the cost worth it.

Is The SPAC Boom Too Frothy To Justify?

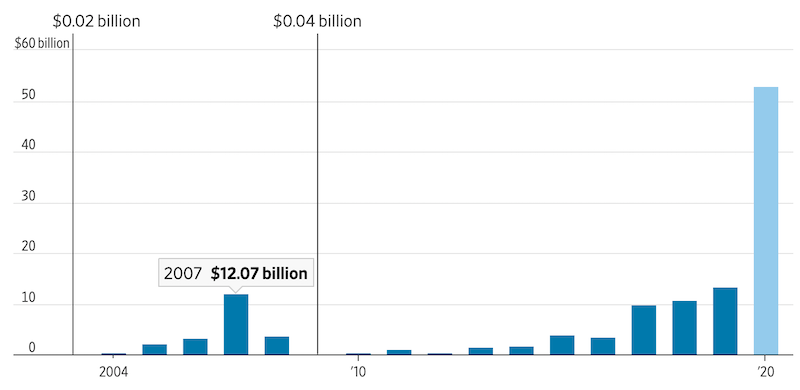

The last SPAC boom peaked in 2007 when the market was similarly more speculative in certain areas and risk-taking was fashionable. Back then, SPACs raised over $12 billion total. In 2020, they raised over $53 billion just through mid-October.

(Source: Dealogic)

Adding 2019 and 2020 together gives you more SPAC money raised since the rebirth of the concept (in 2003) through 2018.

Many SPACs Merge With Pre-revenue Companies

At least 21 percent of the companies taken public through a SPAC in 2020 were pre-revenue according to regulatory filings.

Companies that go public under the SPAC structure often drum up their future growth expectations. This practice is more constrained under the standard IPO process.

Due to legal differences between SPACs and companies going via traditional IPOs, startups going public through “blank check” companies can give more optimistic projections about their growth.

In traditional IPOs, companies that disclose rosy projections – without seeing those figures transpire – could face lawsuits.

Going Mainstream

Even celebrities without finance backgrounds like Shaquille O’Neal have their own SPAC, which doesn’t seem far off from Katy Perry asking investing luminaries like Warren Buffett about buying bitcoin.

Companies generally like to list their companies publicly during rising markets. When markets rise, people are wealthier and looking for new opportunities. When an increasing amount of capital is chasing a slower growing supply of securities, this drives up prices, decreasing their forward returns.

They’re ready for a new supply of compelling securities and investments to hit the market, even if the returns aren’t great going forward.

SPAC managers will also be incentivized to enter into a deal if the deadline to invest or return investor money is coming up lest they have to return the money. This can make for suboptimal deals.

In an environment where prices are already high, there’s generally too much capital going after too few quality deals.

This is a less than great scenario for SPAC investors. It still might beat terrible cash and bond returns, but the risk is high as well.

They can always reject a deal that is overpriced. Or even choose not to take part even if other investors want to move forward.

But another issue is that there is less disclosure, which is both a pro and a con. The main con is that it is harder to evaluate deals as with a traditional IPO process.

Softbank

For example, had Softbank introduced its SPAC a year earlier, it might have been able to get WeWork public without the scrutiny it went through on its financials and governance concerns that ultimately led to the process being scrapped.

The company may have went public through a high valuation before sinking once public.

This is inherently the main flaw in an IPO, in general, SPAC or not – those selling their shares in the business upon going public have more knowledge about the company than the new investors who have less information.

This doesn’t necessarily answer the question on whether the SPAC boom meets the definitive signs of a bubble.

Are SPACs structurally taking more share away from the traditional IPO process due to their ease and simplicity? In other words, is it a better model?

Is the low interest rate environment boosting their popularity simply because investors have a more limited set of opportunities to park their money? (It’s certainly part of it.)

From the perspective of nearly non-existent returns in cash and bonds, the valuations of stocks are just the risk premium.

If the risk-free rate is no longer part of the discount rate (because the government cash or bond yield is gone or even negative) and the risk premium declines as investors reach for yield in a world of few alternatives, it’s not out of the question to see P/E ratios that are 2x to 3x higher than what they’ve been historically.

SPACs are rising with the tide of most equity investments – at least for now.

Trump’s SPAC

Digital World Acquisition Corp. (DWAC), went from $9.96 per share before the announcement to a high of $175 per share — a jump of 17.6x.

Even in the speculative world of SPACs, that’s a massive rally, reflecting heightened interest among retail traders looking to make money quickly.

Given the polarizing nature of Donald Trump’s celebrity as a former US President, and being very much still actively involved in politics, anything with Trump’s association was bound to be a huge meme stock sensation.

The implied value of the new company is more than $8 billion, depending on the exact price.

Since Trump owns more than 50 percent of it, based on SEC filings, it would make him the richest he’s ever been.

In other words, Trump became wealthier in a day or two of SPAC-related meme stock action than the wealth he accumulated over several decades from complex real estate transactions.

Bank Fees Received From SPACs

Banks find buyers for a company’s shares and help the listing run smoothly by backstopping the share price.

SPACs generally get a fee of about two percent of the money raised in the listing and another 3-4 percent when the SPAC acquires its target.

That 5-6 percent in total is slightly less than the amount raised in traditional IPOs for smaller deals.

Capital raises in the $500 million and under range for standard IPOs are commonly in the 6-7 percent range. In other words, a $500 million IPO will typically net an investment bank $30-$35 million in revenue.

As IPO sizes get larger, the fees usually come down as a percentage of the deal and tends to have higher variance.

Investment banks can still earn more than that 5-6 percent total on SPAC capital raises by advising a company on its SPAC transaction or raising more overall money for the purchase.

Criticisms Of The SPAC Blank Check Structure

SPACs have been criticized for circumventing important regulatory matters that can make it easy for the SPAC promoters to mislead investors.

For example, some SPAC creators may make lofty projections to investors when companies are taken public through a SPAC. The stock reacts to such expectations by going higher, if they’re believed to be credible. SPAC sponsors are then able to sell those shares before such targets are hit, if they ever come to fruition.

Such projections are not allowed under traditional IPOs and represent a key form of regulatory arbitrage that’s aiding the popularity of the SPAC blank check structure.

Many traders and investors are generally hesitant about the idea of buying into new IPOs, in general.

This is because the seller has an information advantage over the buyer. Sellers who have the inside scoop on the business will know more about its operations and how to price the company than most of those on the outside will be able to do.

This issue can be exacerbated when there are short lock-up periods on the sponsor’s equity.

A 12-month lock-up period is typical. This is normally set in place to better align the SPAC sponsor’s incentives with investors. That way, the sponsor can’t bag a large profit as soon as the company goes public and has to have skin in the game in the early stages.

Some agreements enable early release (i.e., partial or full annulment of the lock-up period) if a company’s shares trade particularly well.

Some lock-up periods might stretch from 24 to 36 months to better ensure sponsors are working with investors. Selling a lot of shares can hurt a company’s price and essentially offload losses onto individual investors.

Securities and Exchange Commission official John Coates asserted there are “some significant and yet undiscovered issues” with special-purpose acquisition companies, given they bypass some of the standard safeguards of a traditional initial public offering.

The Fall In SPACs

When the 2022 global central bank tightening came, traders and investors coming out of risky trades squeezed SPACs that were running out of time to find companies to take public.

This could potentially leave their creators without viable deals and saddle them with large losses.

Firms that have gone public through mergers under the SPAC structure tumbled alongside the technology sector and cryptocurrencies.

These sectors tend to be hurt the most during a monetary tightening due to their longer duration making them more sensitive to changes in interest rates.

Disruptions in supply chains and technological setbacks have challenged many startups, combined with worries about high inflation and rising interest rates and that impact credit and overall capital availability.

An exchange traded fund tracking companies that have merged with SPACs fell about 1.5x as much as the broader market.

Some previously popular stocks such as sports betting firm DraftKings and personal finance startup SoFi Technologies have slid 50 percent or more from their peak.

Shares of companies taken public by some of the most popular SPAC architects, such as Chamath Palihapitiya (one of the most publicly popular venture capitalists), have fallen.

Those declines have slowed the creation of new SPACs and the pace of deals to a fraction of 2021’s record levels.

They have also caused some companies that had previously agreed to go public through SPACs, such as savings and stock trading app Acorns, to call off the deals and attempt to raise money through private markets instead.

The slowdown mirrors weakness in the broader market for initial public offerings, which suffered a notable slowdown with 2022’s tightening.

Blank-check companies’ creators typically have two years to find a company to take public, a unique element of the SPAC structure.

Otherwise, they must return money to investors and forfeit the $5 million to $10 million on average that they pay to set up the SPAC firms through lawyers and auditors and evaluate potential mergers.

How Can The SPAC Blank Check Company Structure Be Strengthened?

Longer lock-up times can better help align SPAC sponsors with those of the company and long-term investors.

It will also naturally take away some of the incentive to make overly optimistic projections to inflate a company’s share price and take advantage by unloading shares soon after going public.

SPAC sponsors can also better align themselves with the company and investors by taking a smaller cut on the transaction.

The end goal is for the sponsor to have its goals aligned as closely as possible with other stakeholders and outcomes that are beneficial for everyone involved. Namely, to profit from the company’s performance, rather than hyping up a company through quixotic projections and opportunistically offloading it.

SPACs have become a popular vehicle to take a company public. And with that will come greater regulatory oversight. Instances of where regulatory loopholes exist – i.e., that can create potential information asymmetries – are making SPACs a very popular method of IPO’ing.

Whether the blank check structure stands the test of time as an ongoing widespread vehicle for going public will largely depend on the laws and regulations surrounding SPACs.

Conclusion

A SPAC is used as an investment vehicle to raise money to buy another company in the form of an IPO.

At the onset, these blank check companies have no business operations or any deal in place to acquire a company, or even a known list of targets. They must typically make an acquisition within two years or have the SPAC liquidated with funds returned to investors.

All types of investors can be involved in SPACs, though they are typically private equity firms or hedge funds given the need to acquire a “late stage” firm looking to enter the public markets.

Startups in buzzy verticals – such as online gambling, electric vehicles, cannabis, and space travel – are increasingly going toward special purpose acquisition companies (SPAC structures) that offer potentially large rewards to backers while circumventing some of the safeguards associated with traditional IPOs.

When such a vehicle merges with a target firm, the company takes up the SPAC’s spot on a stock exchange, thereby enabling it to sell shares to the public.

This generally increases the company’s value given a broadened investor base (including individual investors) and provides more liquidity for its shares.

SPACs, essentially, are a form of legal regulatory arbitrage.

Given the risks associated with many companies going public through SPACs – many are pre-revenue, have very low revenue, don’t make a profit, or don’t have a clear path to making money – they are highly speculative.

Though many retail investors are generally attracted to highly speculative companies in newly popular sectors, they can be dangerous as the risk of losing one’s entire investment is quite high.