11 Ways to Hedge Equity Risk

Whether you trade stock indexes, pick individual stocks, trade ETFs, or have other equity exposures in your portfolio, you may consider ways to hedge equity risk to reduce potential losses.

Stocks are a volatile asset class and common shareholders are the most junior stakeholders in a business. A stock conveys a share of ownership in a business. You are the last to get paid and bear all the risk if the business fails.

This provides great upside but also material risks.

Most portfolios have lots of equity exposure. Stocks can experience painful drawdowns, either as individual securities or the market as a whole when the market begins discounting a different set of future expectations.

As such, this article is dedicated toward how to hedge your stock market exposure in various different ways.

What is portfolio hedging?

Hedging is used to reduce the risk of loss to an investment. Hedging often involves using a type of instrument (e.g., security, derivative) that increases in price when a particular investment or portfolio drops in value.

The profit derived from the hedge helps to offset some or all of the losses sustained to a portfolio. (Or in certain cases, more than all.)

Various strategies exist to help hedge certain types of risks.

For example, if you own a stock, that’s a linear exposure. So a hedge on stock exposure hedges delta risk.

If you own an option, that’s a non-linear exposure, so a hedge on an option exposure might involve hedging gamma.

Other types of hedging can be used to help offset foreign exchange risks, interest rate risk, duration risk, inflation risk, or “hidden” or inadvertent exposures. (For instance, having a call on airline stocks is an implicit bet on the price of oil.)

How to hedge equity risk

Hedges may protect:

- a single security

- an entire market exposure

- a specific sector exposure, or

- a particular type of risk (e.g., inflation, FX, duration, etc.)

For example, tech companies tend to be longer duration in nature. Their cash flows are discounted to come further out in the future relative to other types of stocks. This gives them structurally higher volatility.

In turn, that makes them more vulnerable than most stocks to a rise in interest rates.

So, because of this correlated exposure, a trader may choose to take an OTM put option on interest rates or longer duration government bonds to help reduce this risk. Or even short some amount of longer duration bonds.

Many traders choose not to hedge individual securities, and instead hedge for overall market risk.

If an individual security presents too much risk in a portfolio, the position size should probably be reduced. That way it won’t single-handedly create undesired volatility or risk excessive capital loss.

Choosing the best type of hedge

Hedging at the overall portfolio level would generally be done with respect to an index.

If a US portfolio is more evenly weighted toward large cap stocks (as most stock portfolios are), hedging based on the S&P 500 index could make sense.

If a portfolio is more tech-weighted, the NASDAQ might be more appropriate.

If geared toward small caps, the Russell 2000 might be a better match.

None will be perfect, but a reasonable hedge could be constructed using an index.

On top of that, because many stocks are included in an index, it is less volatile. Therefore, the hedge on an overall market index in the form of a put option is cheaper than it is for a single security.

It’s not uncommon for a stock to go up or down more than 5-10 percent in one day (or more). But this occurs rarely with diversified indexes.

Buying an option entails paying a premium for somebody else to essentially manage the risk for you.

You can also buy something else to help reduce your risk. For example, a popular form of diversification is buying bonds, since they do well in a different type of market environment. The same can be said of something like gold.

Short selling an asset is a common type of hedge. It carries more risk, but it is, on the surface, cheaper.

With a put option, you pay a premium but it only kicks in once in-the-money (ITM). If you buy an out-of-the-money (OTM) option you still have risk to bear up until the strike price.

Hedging is imperfect

Hedging is rarely perfect. If it was, there would be little to no upside to be had in a portfolio. There is always some risk-taking that will be involved, and return will be proportional to risk taken on.

Good traders and investors will calibrate a portfolio to a level of acceptable risk and volatility they want and use hedging arrangements to achieve their goal of having the desired upside without the unacceptable downside.

Risk will not be removed entirely and only part of a portfolio will be hedged.

Ways of hedging equity risk

Some ways of hedging equity risk involve options. Some involve buying or selling something. Or different tactics (e.g., portfolio construction).

An option is a contract that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an asset at a specific price.

For instance, one AAPL 130 call gives the buyer the right to buy 100 shares of Apple stock (AAPL) at a strike price of $130 per share.

With an American option, an option can be executed at any point before the expiry date, if ITM.

With a European option, it can only be executed if ITM on the expiration date.

A call option gives the buyer the right to buy a certain amount of the underlying asset (100 shares in the case of a standard vanilla option) at the strike price.

A put option gives the buyer the right to sell a certain amount of the underlying asset at the strike price.

The price paid for an option is called the premium.

Deep OTM options are less expensive because they have less intrinsic value. They have a low probability of landing ITM, so their price is cheaper, reflecting the likelihood that they’ll only occasionally have value at expiration.

Deep ITM options are more expensive because they have more intrinsic value. The more ITM an option gets, the more the option begins acting like the underlying asset.

Therefore, from a hedging perspective, OTM options work less effectively than ITM options at hedging the underlying. This comes at the trade-off of their price, with ITM options being more expensive than OTM options.

The option hedge is a limited-risk way of reducing the impact of a decline (or adverse move, more generally) in the underlying asset that will cause a decline in the value of the overall portfolio.

This can be achieved with just a single option expiry or it can be accomplished with multiple options.

We’ll go through each strategy individually. These will include:

- Long puts

- Put spread

- Covered call

- Collar

- Fence/Dutch rudder

- Short selling

- Diversification

- Cash

- Owning volatility

- Inverse ETFs

- Reducing position size

1) Buy a put option

A long put option is simple way to cut off left-tail risk. But it also is fairly expensive.

Those who sell options generally mark them up at a slight premium such that the implied volatility of the option is likely to be greater than realized volatility.

Let’s say you own 100 shares of Proctor & Gamble stock (PG). It trades at $128 and you want to cap your downside at $100 per share.

In other words, you don’t want to risk more than about 22 percent on that one position.

For a 10-month hedge, it would cost $3.00 per share, or about $3.60 extrapolated out to a year.

At the current share price, that hedge costs 2.8 percent.

While in some years it will help avoid losing some amount of principal, that’s also going to eat up a lot of your returns.

You can also lose some smaller amount than 22 percent (price remains above $100) and have an unrealized loss plus lose the premium on your option.

Your payoff diagram looks something like this, with risk capped at a downside of $100 per share and breakeven slightly above the current price ($128) because you need some gains to help offset the cost of the option.

Long put option payoff diagram

For this reason, many traders and investors choose to limit their exposure to individual positions rather than hedge them directly.

For instance, if you have 10 percent of your wealth in a company’s stock and seeing it decline by 50 or more percent would be too painful, it would be prudent to diversify.

Many like concentrated portfolios because they believe it will give them better gains, to keep things simple, or because of conviction. But the discounted set of expectations is already baked into the price, so you can never be too sure of any particular investment asset.

For that reason, some traders and investors will choose to not have any more than five percent of the net value of their portfolios in any given asset. Some will go further by limiting it to 1-2 percent, though this is difficult to follow for beginners, in particular.

But, by and large, limiting position sizing limits the need to hedge, which can be expensive.

When traders hedge, they’ll usually use OTM options. They’ll be cheaper than something close to at-the-money (ATM), but they won’t protect the portfolio against the initial declines against the asset.

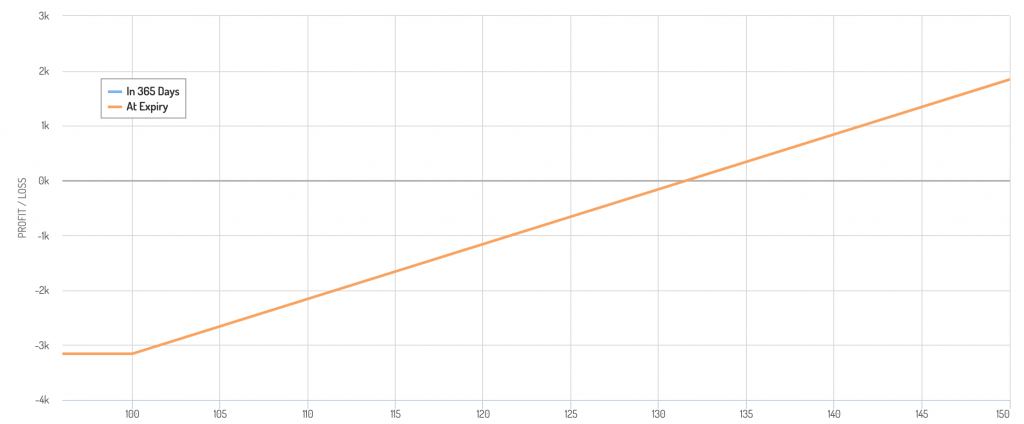

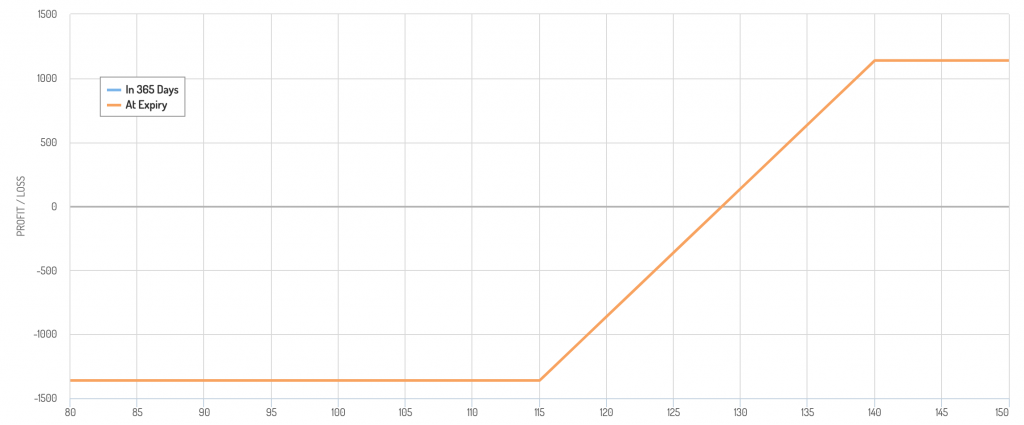

2) Buy a put spread

A put spread involves being both long and short put options on the same underlying asset.

A put spread is used to cheapen the cost of the hedge. Some of the premium received from the short put will help offset the cost of the long put.

Taking our previous example of PG, if you wanted tighter risk management, instead of a 100 strike put, you could buy a 115 strike put.

That’ll more than double your premium, from about $360 for one contract to about $820.

Instead, you could sell the 90 strike put, which provides you around $170 in premium.

The cost of your overall hedge is the difference between the two – $820 minus $170 = $650

$650 is more expensive than $360. You pay $310 more to potentially save an additional $1,500 in prospective losses.

At the same time, the put spread effectively causes your hedge to roll off at a point. Gains on the long put will be offset by losses on the short put. You will also be long the stock (assuming you still have the exposure).

If you have on a 115-90 put spread that means your linear risk exposure to the stock kicks back in below $90.

Put spread payoff diagram

At the same time, you might feel comfortable with this depending on what your goals are.

If at $128, PG trades at a forward P/E ratio of 25x, that means its projected annual EPS is $5.12 ($128 divided by 25).

If it falls to $90, this could be because its earnings are expected to take a hit. It can also be because of other factors that don’t have much to do with the company itself – e.g., rise in interest rates, liquidity dislocation.

In which case, the $5.12 per share would give it an earnings yield of 5.7 percent. The inverse is the P/E ratio (17.6x, or 1 divided by 0.057).

At that point, you might consider PG to be a good value and be comfortable with not having downside protection.

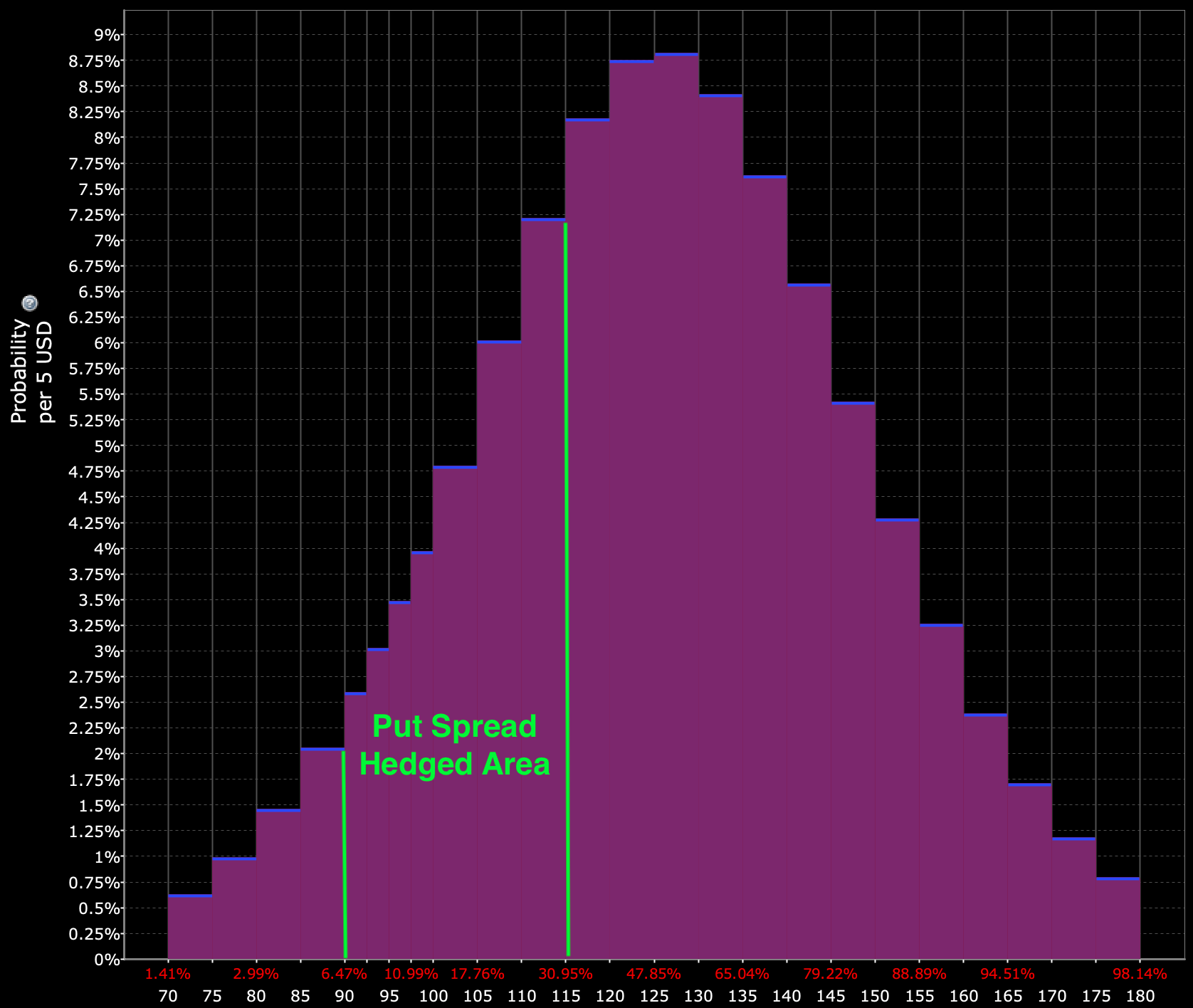

Thinking of things in terms of a probability distribution, the $90 to $115 region has more bulk to it. In other words, you’re hedging out a material fraction of the left-tail distribution (in this case, about 25 percent of the expected range of outcomes).

(Source: Interactive Brokers)

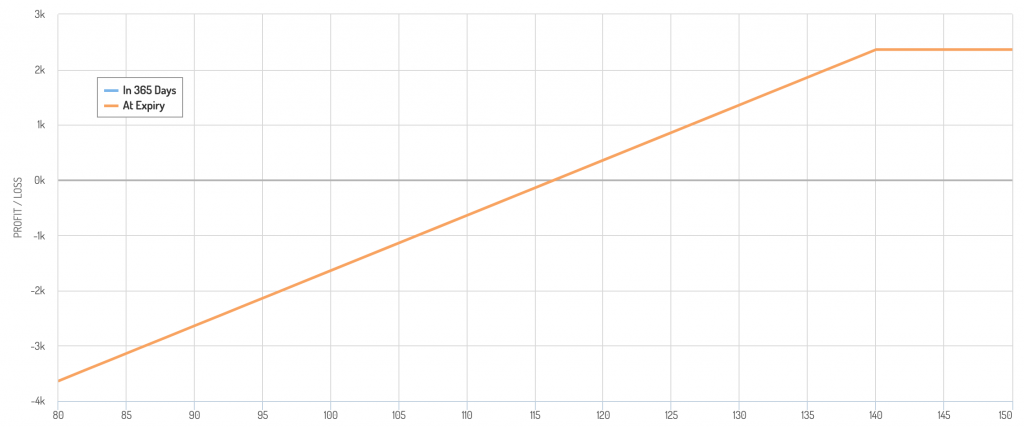

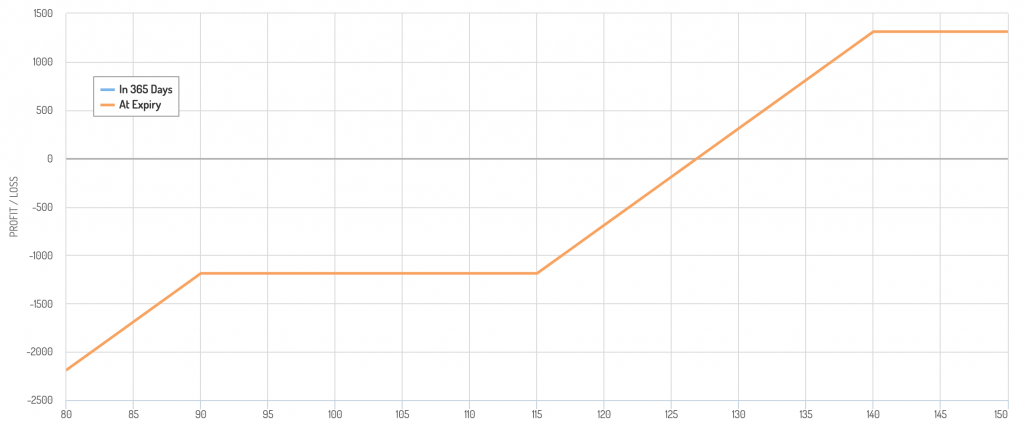

3) Covered call

A covered call involves selling a call option on a stock you already own.

This caps your upside but brings with it the benefit of having a weak hedge in the case of a decline.

For example, let’s say on PG you wanted to cover your position at $140 per share. You believe at that price it’s relatively high and a good place to sell if you had the opportunity.

Covered call payoff diagram

A 140 strike call with an expiration one year out costs around $760. You sell this as part of the covered call, so you’re entitled to this premium.

$760 divided by $12,800 (the price of 100 shares, given 100 shares per options contract) is about 6 percent.

So you get upside of about 9 percent ($140 divided by $128) and you get the 6 percent premium. Your total upside is about 15 percent.

Considering the nature of PG – a consumer staple stock, or more defensive flavor of equity – that’s not bad.

Your downside is that you can’t participate in more upside than 15 percent. Your hedge is also quite weak, as it only hedges against a 6 percent loss.

So, a covered call will protect you from some losses, but not a lot.

Pair with a put option?

For this reason, some traders like pairing a covered call with a long put option.

This structure gets to take advantage of the volatility risk premium and mild hedge benefits associated with a short call. At the same time, it also involves having more clearly defined downside protection with the long put.

This is called a collar, which we’ll discuss in more detail in the next section.

4) Collar

As mentioned, a collar involves buying a put option and selling a call option.

It is analogous to the idea of a covered call, where you forgo upside for the benefit of receiving option premium on a stock you already own, while buying the put option.

The cost of the put option is partially or fully paid for by the premium received from the short call.

It also gives you a more defined upside and downside.

If the underlying rises above the call option strike price, the call will result in losses that will be offset by gains in the stock.

If the underlying goes below the put option strike price, the underlying asset will have losses that are offset by the put option and the premium from the short call option.

The benefit of the collar is that it’s more price neutral.

You don’t have to suffer large drawdowns in the underlying because of the put option.

You receive some income to help offset the price of the put from the call. To maximize the amount of income received, one could place the short call ATM.

Studies have shown that the volatility risk premium (VRP) has a higher Sharpe ratio than the arguably more competitively sought after equity risk premium (ERP), giving covered call strategies (and some of their offshoots) higher overall Sharpe ratios than vanilla equity strategies.

Puts tend to be more expensive than calls in equities. This is because people are more risk-averse and tend to pay more for puts than calls.

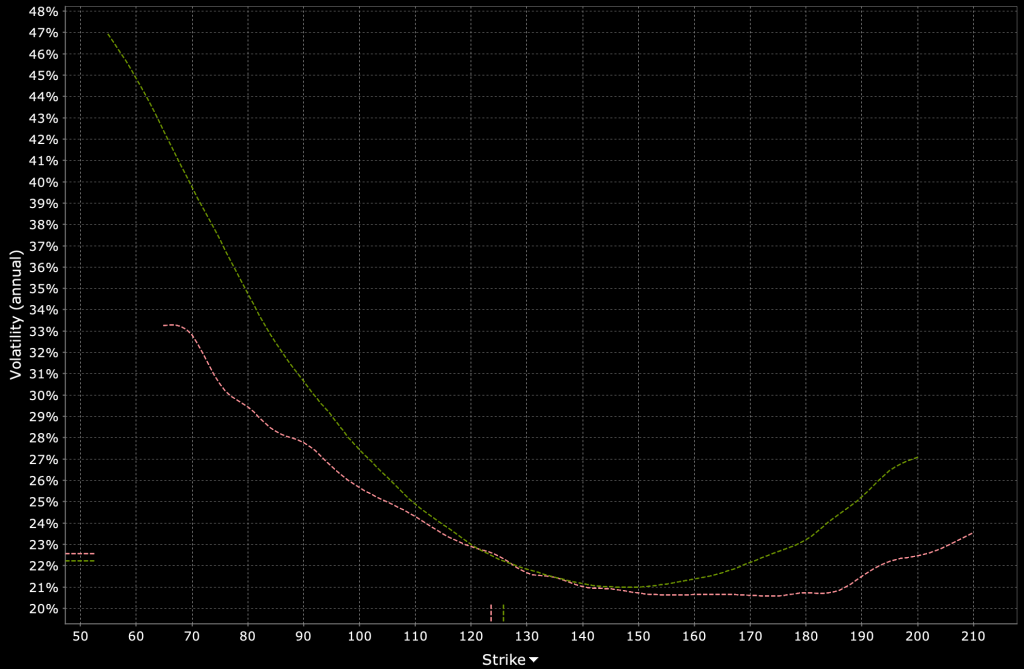

You can see this behavior in the volatility skew that compares the implied volatility of options across a range of strike prices. The higher the implied volatility the more expensive the option.

Volatility skew in equity options

(Source: Interactive Brokers Implied Volatility Viewer)

For a 140 call-115 put collar on PG with a current trading price at $128, the put is slightly further away from ATM ($13 per share away) relative to the call ($12 per share away).

But the put is more expensive because of the (normally) higher demand for puts relative to calls.

In terms of a payoff diagram, a bullish collar looks like this.

Bullish collar payoff diagram

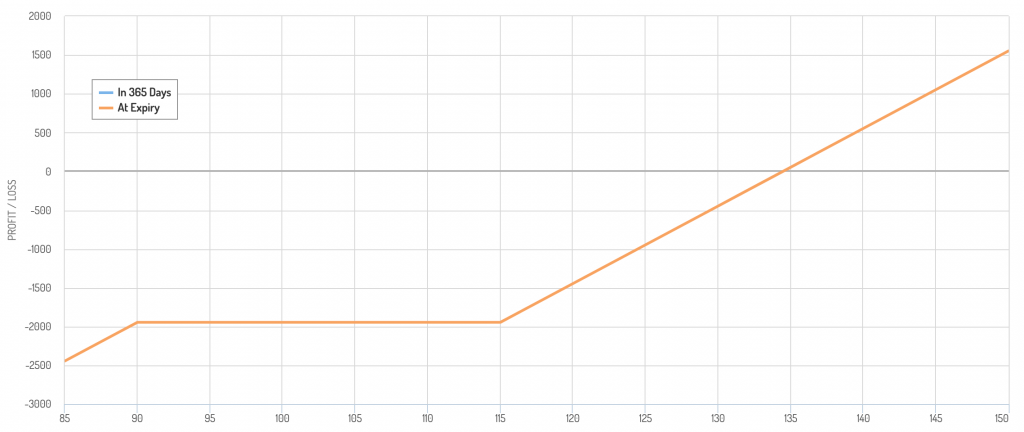

5) Fence or Dutch Rudder

A fence (sometimes known as a Dutch rudder) strategy is the combination of a covered call and put spread.

Three options are used plus a position in the underlying.

- Long underlying asset

- Short OTM or ATM call option

- Long OTM put option

- Short OTM put option below the expiry of the other put option

Like the covered call and collar, the fence is a defensive position.

The trader sacrifices upside for downside protection. For a stock, the trader can still obtain dividend payments (unless the call option is ITM and the other party decides to exercise early to obtain the dividend).

The fence provides the combined benefits of the covered call and put spread.

i) Premium from the short call option to provide income

ii) Downside protection from the long put option partially or fully paid for by the short call

iii) Additional expense reduction by shorting a put option at a strike somewhere below the first one

A fence provides the ability to have more of a risk-neutral position, while:

- being able to collect dividends

- potentially have some price upside, and

- having relatively cheap downside protection by selling two options versus being long only one

For PG, a short 140 call / long 115 put / short 90 put fence would have a payoff structure like this:

Fence (Dutch rudder) payoff diagram

There is the left-tail risk from shorting the put, but for a value investor going back to a linear, delta-1 position could make sense because the security has become fairly cheap at that price level.

6) Short selling

Short selling is a straightforward way to hedge risk exposures from being long certain assets.

For example, let’s say you want to own ExxonMobil stock (XOM) but don’t want to have your portfolio so exposed to movements in the price of oil.

To do so, you could short oil futures or an oil ETF to hedge some of that exposure.

To reduce equity risk, short selling is often the cheapest and most efficient way of hedging out some of your exposure.

If you short cash equities, you also get a cash credit to your account. That can reduce the amount you’re borrowing on margin or give you a positive cash balance off which to obtain interest.

Borrowing also comes with an interest cost, which can sometimes be very high if there’s large demand relative to the number of available shares.

For “easy to borrow” shares, the fee is often 0%-2% interest per year. For “hard to borrow” shares, the fee can be exorbitant to the point where it makes short-selling practically off-limits. The interest percent can be in the hundreds or even thousands.

Short selling stocks or futures is a cost-effective way of hedging stocks against an expected short-term decline. Futures can also be used to limit the capital commitment.

Some traders may choose to short while also pairing with a short put option.

In a strong bull market where prices are going higher, a trader might wish to reduce equity exposure while at the same time not want to lose too much by effectively putting on a covered put.

If stocks keep going up, the premium received from the put option will help offset some or all of the losses.

The drawback, of course, is that once the put goes ITM then the short equity exposure ceases to serve its purpose as a hedge.

7) Diversification

Different assets and different asset classes have different environmental biases and thus will act differently.

Diversifying well will improve your return relative to your risk better than anything else you can practically do.

When equities fall in price, there are typically other assets or trades you can put on that will help increase in value to help offset these losses.

This can include owning nominal rate bonds, inflation-linked bonds (ILBs), gold, commodities, certain currencies, volatility, privately held assets that can keep providing you income, liquid alternatives, and so on.

Balancing your allocation well will reduce your overall drawdown and is likely to give you shorter underwater periods, among other benefits.

We have other articles on the site dedicated to the concept of diversification and building a balanced portfolio.

- How To Build A Balanced Portfolio

- Building a Balanced Portfolio with Options

- Building a Balanced Portfolio with VRP Overlay

- Balanced Beta: Efficiently Balancing Risk, Not Capital

- Simple Portfolios: Improving Outcomes by Simplifying

- The Barbell Portfolio Strategy

- How to Improve Risk-Adjusted Returns

8) Cash

Cash doesn’t have a lot of volatility to it, so it’s perceived as a safe asset. However, cash’s value declines over time, making it a risky asset. Also, in developed markets, cash doesn’t have any yield, so there’s not direct investment return.

Central banks are going to target an inflation rate of at least zero, so people will be incentivized to invest their money so it doesn’t lose its value.

However, owning some cash can be very helpful for purposes of having liquidity and optionality, and never having to worry about margin calls, which force you to sell at the worst times.

Cash enables you to take advantage of those times when there’s a large decline in asset prices that you can buy rather than having to be one of the many who to sell to raise cash.

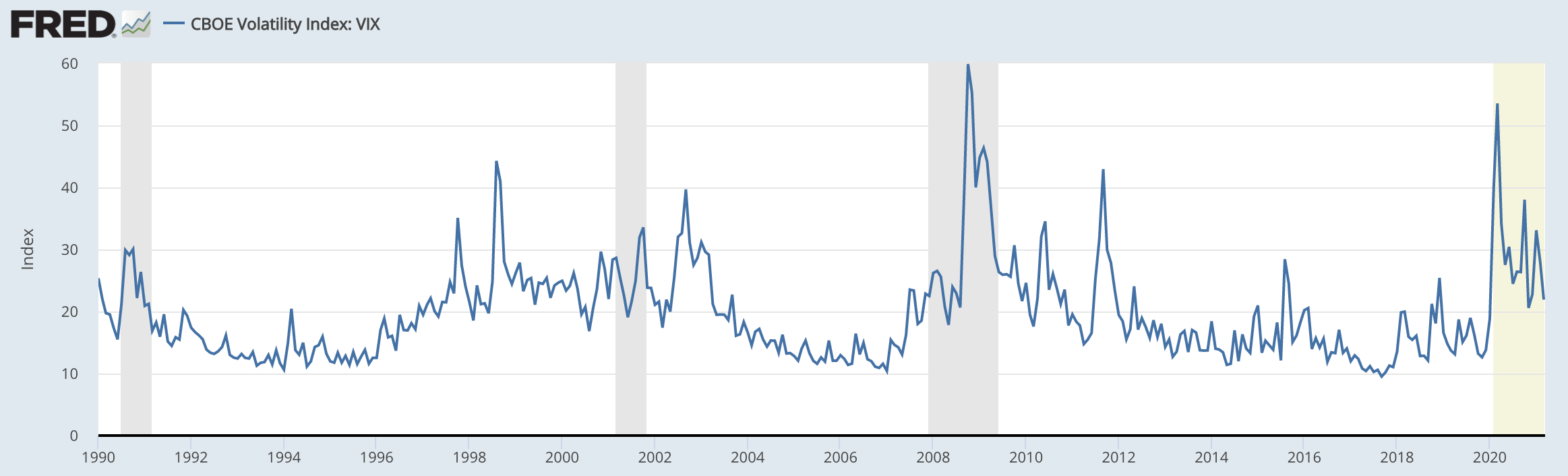

9) Owning volatility

When equities fall, there are typically large spikes in volatility.

VIX is the most popular volatility index, established in January 1990 by the CBOE.

This happened notably in 1997 (Asian balance of payments crisis), 1998 (Russian default, LTCM), early 2000s (tech bubble crash), and 2008 (financial crisis).

VIX Index: January 1990-Present

(Source: Chicago Board Options Exchange)

Owning volatility was valuable as a way to hedge equities.

The VIX index is an index of the implied volatility of a variety of options on the S&P 500. There are futures, and options and ETFs based on those futures.

These generally gain when stocks drop in value.

Volatility is, however, one of those products that tends to lose value as time goes on.

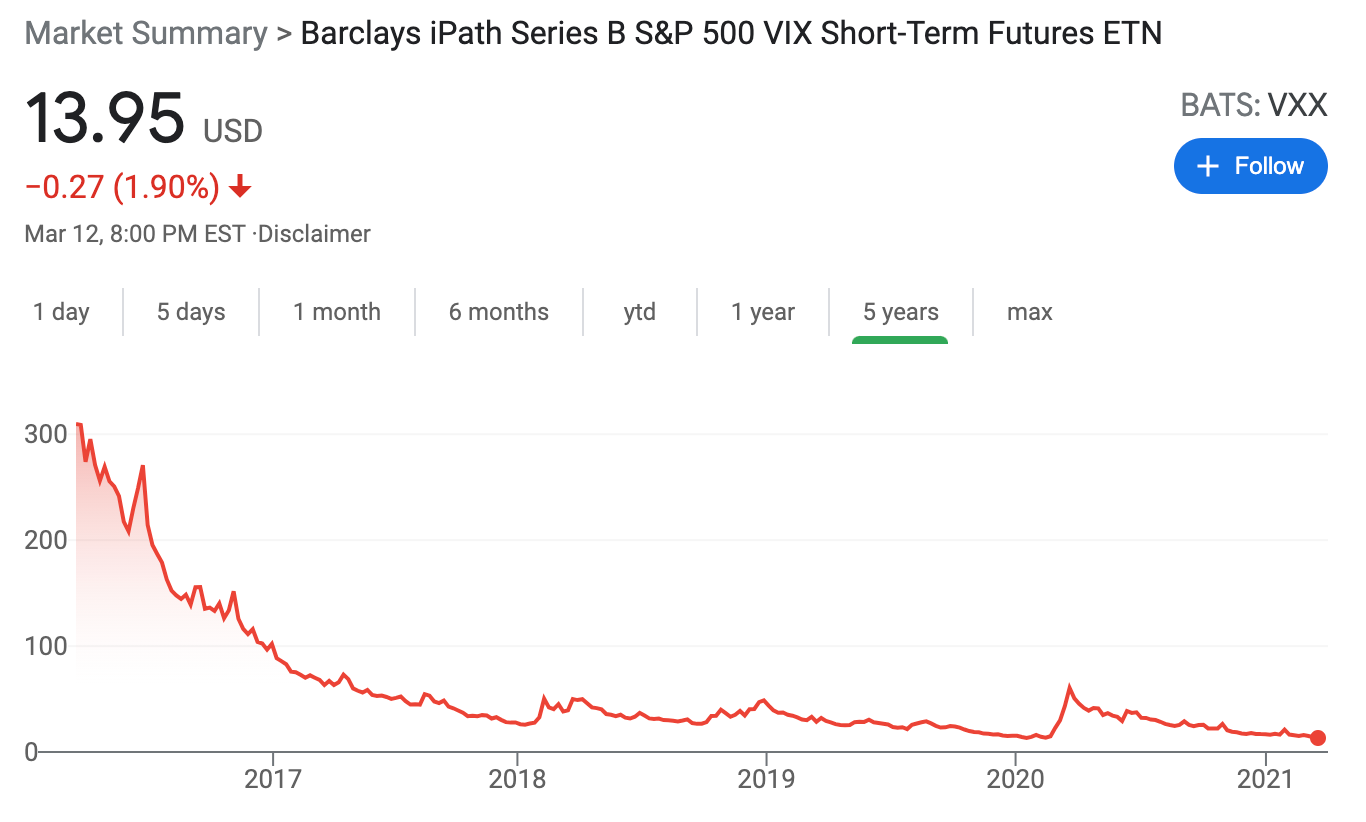

As an example, below is a chart of the VXX ETF that’s tied to the VIX index.

The “slow bleed” nature of these products is sometimes offset by big gains when a dislocation or big risk-off event occurs.

The 2018 and 2020 upward “blips” shown in the above graph appear small but were huge percentage gains.

Volatility is also a component of standard vanilla options. But it is less of a pure volatility product because of the delta component (i.e., movement of the underlying).

Some exotic options also serve as pure volatility products, such as volatility swaps.

10) Inverse ETFs

Inverse ETFs effectively short certain exposures, such as being short the S&P 500 or short the NASDAQ.

They appreciate in price when the broader market declines.

Some of these are leveraged instruments, which makes them poor choices for trading beyond the daily timeframe.

Leveraged ETFs theoretically give you more bang for your buck, as you get more hedging capacity for less capital commitment. However, leveraged ETFs also come with a decay element.

They need to be handled carefully if used for anything beyond day trading purposes. This is because their values are recalculated every trading day.

In light of this, percentages matter rather than the value of the index. If the value of something falls 20 percent, a 25 percent gain is needed to make back the losses and leveraged ETFs reflect this.

For example, if an index drops from 100 to 99 it loses one percent of its value.

If the index rallies back to 100 the next day that would be a gain of 1.01 percent.

A 2x leveraged ETF of the underlying index would drop 2% from 100 to 98.

The next day, the ETF would rally 2.02 percent to follow the index (2 multiplied by the 1.01 percent gain).

However, following the daily reset, doing the calculation, taking 98 multiplied by 2.02 percent gives us only 99.98.

Further price movement compounds this tracking error, with higher volatility causing a higher resulting discrepancy.

As a result, there’s a natural decay pattern in these leveraged ETFs that distorts how effectively they will mirror what it’s supposed to be tracking over the long-term – i.e., anything longer than one day.

If the market does decrease and you’re long a 2x or 3x leveraged short ETF, you will make money in excess of simply being short a straight 3x short S&P 500 ETF like SPXU.

But it won’t be the 3x many might assume they’ll be getting unless limiting the holding period to within just a single day.

The advantage of these securities, however, is that they can be traded in a regular stock trading account for those who lack futures and options accounts.

Nonetheless, the leveraged varieties should ideally be avoided for those who have holding periods beyond one day due to the tracking error that results from them.

11) Reduce position size

Being overly concentrated in something increases the necessity to hedge.

If something is 60 percent of your portfolio, such as stocks in a 60/40 portfolio, then there’s a greater risk of that blowing a large hole in your portfolio.

It’s especially true when assets are bought on leverage.

With vehicles like futures, margin lending, some ETF products, it’s fairly easy to make just one asset more than your portfolio size in a few clicks.

But sizing positions appropriately is a part of prudent risk management. In financial markets, the range of knowns are typically low relative to the range of unknowns relative to what’s discounted in the price.

This is especially true for stocks. This is expressed through their high volatility.

Even limiting position sizes within individual securities is not enough, given the high correlation between stocks.

Hedging equity risk can be more effective when diversifying not just by different stocks, but different asset classes, different countries, and different currencies.

How to choose the appropriate hedge

More concentrated portfolios will likely require larger and more expensive hedges relative to portfolios that are well diversified.

Like with anything, there are pluses and minuses to consider and nothing will be perfect.

If a trader has equity exposure that’s equal to 2x the total net liquidation value of their portfolio, they have greater risk to bear from a decline in equities relative to someone with 30 percent of their portfolio in stocks and the remainder diversified.

The trader that runs a more concentrated portfolio could use a larger hedge while the more diversified trader already has a reasonably well-hedged portfolio.

For many traders, investors, and those with retirement accounts, most of their wealth is in equities. Because of the concentration risk, they’re probably going to want to hedge some of it.

If someone has a very long time horizon, a 30 percent or higher drop in the stock market isn’t going to be as adverse an event as someone who is nearing retirement age.

It also depends on the nature of the portfolio.

If someone invests more in US-based technology companies (e.g., MSFT, GOOG, AAPL, AMZN, NVDA), the NASDAQ is going to be a more accurate representation of your portfolio. So using a NASDAQ-related hedge could be most appropriate.

For someone who invests in a variety of larger cap companies the S&P 500 could be a better match for the portfolio.

A portfolio with more overall volatility and higher beta will require a larger hedge.

There are various ways of going about it. Put options, as mentioned, tend to be quite expensive even though they will be effective at limiting your loss beyond a certain point.

You can limit some of this cost by selling call options on your securities. But that will limit upside.

Forming a collar on your position will give you a defined upside and downside and is popular for more concentrated holdings.

Selling a put option below your long put (forming a “fence”) can cheapen hedging costs further but will subject you to further downside if price gets down to that level (at which point you might consider the security cheap anyway and worth having such linear exposure).

You can short sell cash equities or futures as a cheaper, more direct way to hedge, but will limit your returns.

Once you have an idea of what kind of hedge could be best for your portfolio and overall goals, you will need to make a few calculations:

- What is your upside? Will it be unconstrained, or will it be capped (e.g., due to a short call)?

- What is your downside? Will it be capped (e.g., with a long put) or just prudently limited?

- How much will it cost?

There are ways to hedge that don’t have to explicitly cost you – e.g., covered call, collar, fence – but you will need to understand whether those trade-offs (capped upside) make sense for you personally and what kind of protection they provide.

Hedging costs

Hedging equity risk involves paying premiums.

These premiums depend on several variables, including:

- implied volatility

- price of the underlying

- strike price

- time to expiry

- interest rates

The cost to hedge your entire position – i.e., an ATM put – is the most expensive.

For a stock like PG, hedging your entire position ATM (or the expiry as close to ATM as possible) for one year will cost around 10 percent of your total position.

PG is not a stock that can be expected to make 10 percent per year in perpetuity between dividends and capital gains, given its nature as a consumer staple stock.

So it can be difficult to justify the cost of a plain ATM put option.

For this reason, traders will often use OTM puts to hedge. They don’t provide as much protection and they will take time to kick in fully, if they ever do. But they are cheaper and can serve their purpose as protection to avoid a large drop.

OTM puts will also commonly be used in combination with other strategies to cheapen their cost.

i) This can include selling a call. If the stock rose 10 percent and you’d be happy to sell at that price, you could consider selling a call option around that strike price. If it doesn’t get there, you collected additional income from the premium.

ii) You could consider selling a put somewhere below your long put.

iii) You could consider staggering maturities to take advantage of higher premiums that come with time and selling them while being long shorter-dated maturities. (This is an advanced strategy and introduces a mismatch that invites risk, and should be done with caution.)

iv) You can consider overweighting your short call exposure to take advantage of the extra premium, which means you could actually see less profit if the stock went above a certain level.

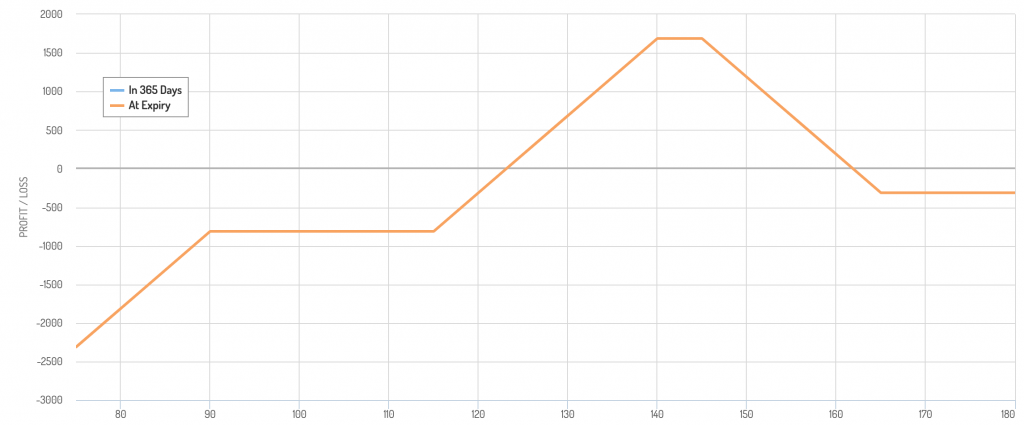

For example, for PG trading at $128, you could sell a 140 call and 145 call, in addition to being long a 115 put, sell a 90 put, while also being long a 165 call to cap risk if the stock appreciates materially.

Your payoff diagram would look like this:

It effectively looks like a modified strangle.

Conclusion

In this article, we included the following as possible ways to hedge equity risk:

- Long puts

- Put spread

- Covered call

- Collar

- Fence/Dutch rudder

- Short selling

- Diversification

- Cash

- Owning volatility

- Inverse ETFs

- Reducing position size

Risk is an inherent part of trading the financial markets.

With that said, risky things are not inherently bad if they’re understood and controlled for. If risk isn’t taken seriously and what one is doing is poorly understood, it can be very risky.

Risk cannot be avoided completely, especially in a cost-free manner, hedging is one way to protect a portfolio against a potential loss.

It can give traders peace of mind that they aren’t exposed to potentially catastrophic losses and help them achieve their goals.

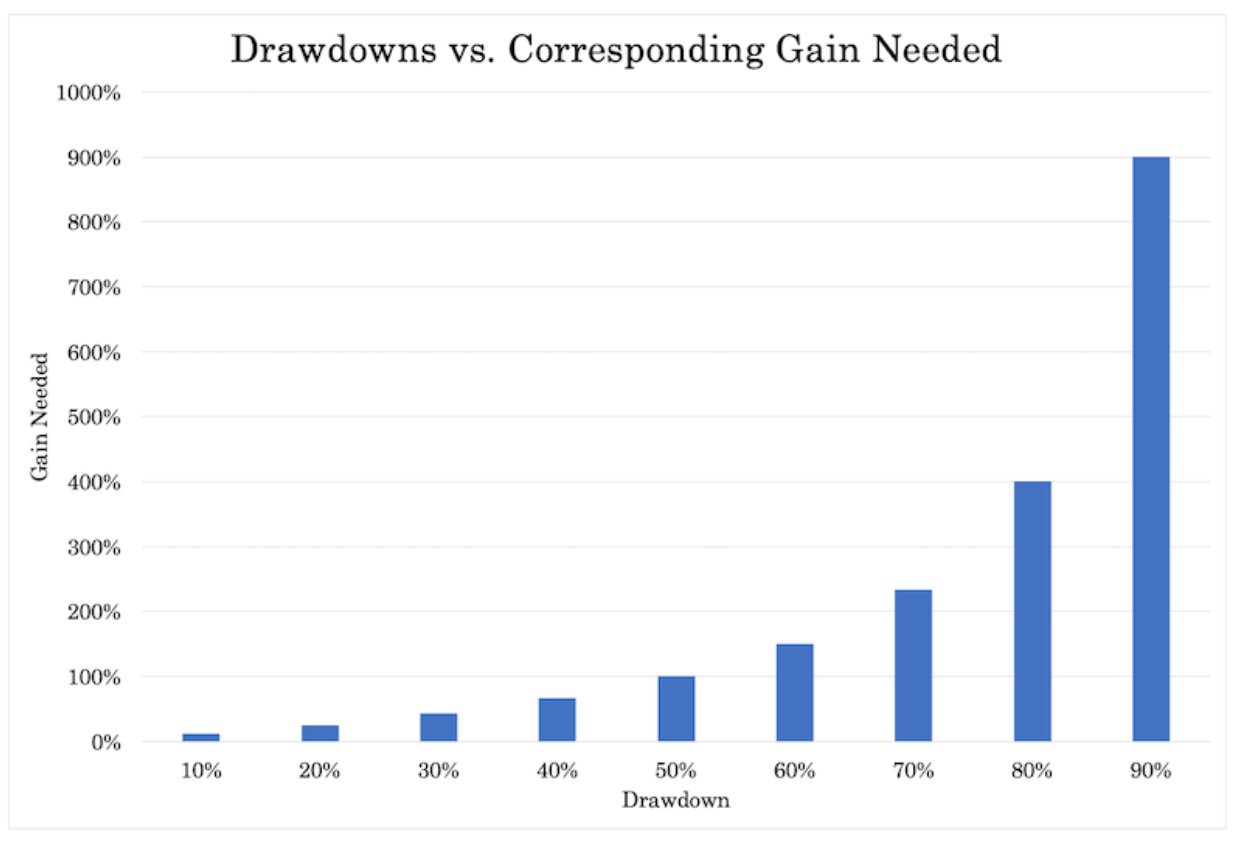

Drawdowns are the most difficult to recover from.

Equal losses are not compensated by equal gains. For example, a 50 percent drawdown requires a 100 percent gain just to get back to breakeven.

So big drawdowns need to be avoided at all costs.

These strategies, or a combination of them, can help traders maintain upside while avoiding the risk of having unacceptable downside.