Currency (FX) and Commodities Trading: A Rebirth in Popularity?

This article was published on March 7, 2021

Given how low cash and bond rates are (and because that’s, generally, how it always is), the nature of monetary and fiscal policy has big effects on currencies (FX) and commodities as well.

In this article, we’ll discuss why currency (FX) and commodities trading are likely to see a rebirth in popularity. At the least, traders and investors will need to think more globally and universally about how they structure their portfolios to achieve quality long-term returns.

While currencies and commodities don’t have the broad appeal of equities because they don’t have obvious yields, they are asset classes that are increasing in importance.

The fundamental reason why involves what drives markets in the first place (money and credit), which is controlled through monetary and fiscal policy.

There are three main categories of monetary policy. This has been covered in other articles in more depth, so we won’t delve deeply into it here. But to rehash briefly:

i) Manipulation of short-term interest rates

Once short-term interest rates hit about zero, they’re no longer stimulative to the economy.

Traditionally, when rates are positive in nominal terms, the lowering of interest rates help to incentivize borrowing. It also helps asset prices due to the present value effect, which increases the value of collateral, overall creditworthiness, incomes, and so on, in a virtuous cycle.

But when interest rates are at around zero, the incentive in the private sector to lend and get money and credit into the economy isn’t there.

Creditors have little return at a point and want to be cautious about who they lend to. Policymakers are going to target an inflation level of at least zero, so zero percent interest rates compress the net interest spread of lenders.

ii) Adjustment of long-term interest rates

Long-term interest rates are most purely the yield on longer-duration securities like government bonds.

Mortgage rates also reflect longer-term interest rates to a large degree (commonly 15-year and 30-year rates in the US). These are tracked by the market since these rates are such a big part of consumer lending. They affect consumer balance sheets and private sector spending.

To lower long-term interest rates central banks will “print” money (i.e., electronic money creation) and buy bonds.

This is commonly called quantitative easing (QE) or sometimes asset buying.

Central banks will normally start with government bonds.

Once those yields become low enough such that duration and risk premiums have gone to very low levels, they will, if necessary, go down the quality ladder.

Policymakers also prefer a steeper yield curve to help preserve banking profitability (i.e., incentivize credit creation) to help both the real and financial economy.

Central banks will then buy corporate bonds and even stocks or equity-like securities.

Some countries, like Switzerland, will even buy foreign stocks. This helps weaken their currency, as it’s essentially a capital outflow.

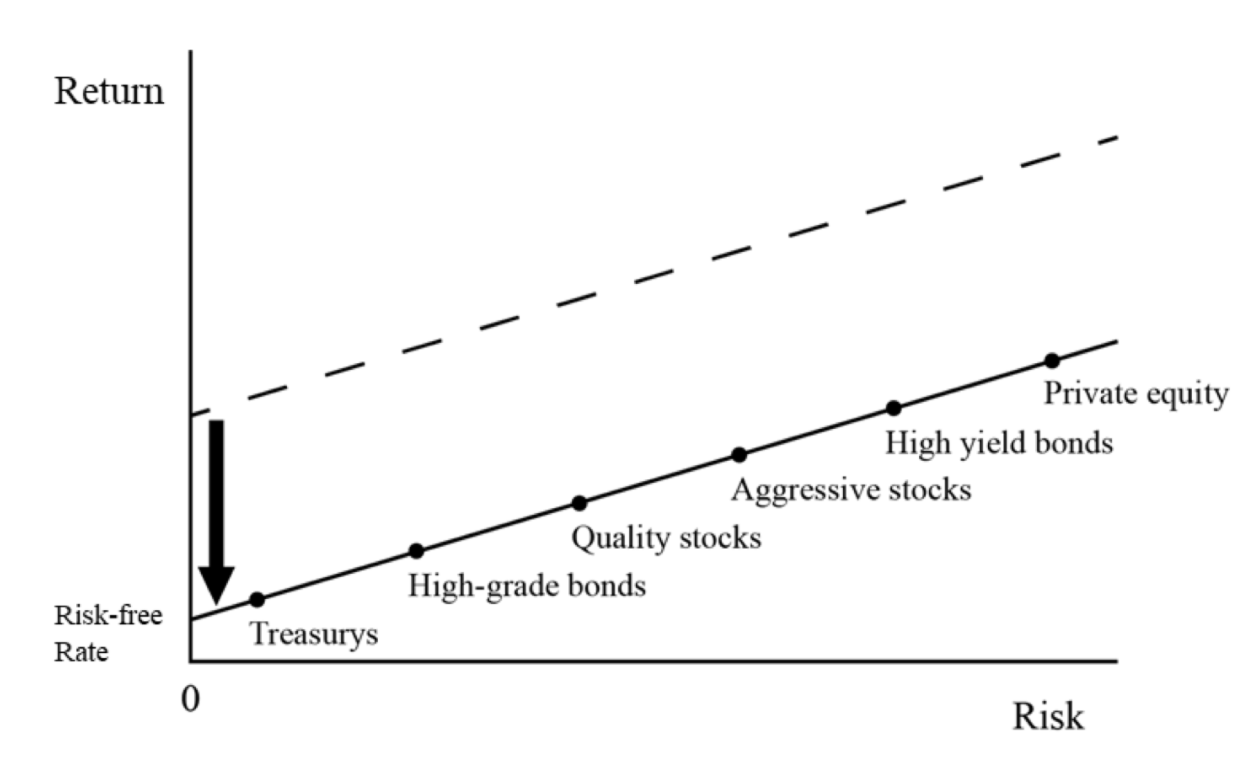

The spreads on these riskier, longer-duration assets can be pulled down relative to cash rates such that QE is no longer stimulative. The graph below shows the conceptual relationship.

When that’s out of room – like it is or close to being the case in the main three reserve currency parts of the world (the US, developed Europe, Japan) – they will need to move on to a third form of policy.

iii) Coordinated fiscal and monetary policy

When the primary and secondary forms of monetary policy lack stimulative capacity and there’s a problem rectifying income, spending, and debt imbalances, they will use the two main levers of policy (monetary policy and fiscal policy) in unison.

In cases where short-term and long-term interest rates are out of gas, it’s hard to get the money and credit distributed effectively.

So, it requires a need for the government to get in the middle of it.

In most countries, monetary policy is outside of fiscal policy. They are two separate set of policymakers – i.e., central bankers and politicians – and each runs itself more or less independently from each other.

This can take various forms.

It can mean monetizing deficits directly – e.g., central bank giving money to the government directly – or participating in direct spending and consumption programs where the government essentially puts money in the hands of consumers/savers and incentivizes them to spend it.

Essentially it depends on how direct or indirect the money and credit is provided and who it’s given to (private sector, public sector, or both).

General impact on markets

As you might imagine, the printing of money is bad for cash and bonds. When you have to print money and create more debt, that’s bad for safer assets.

So, if you look at countries that have zero or near-zero rates with more aggressive “printing” policies – impacting USD, EUR, and JPY – fewer private traders and investors are going to want to hold their cash and bonds.

It is helpful for stocks as a whole. So it does help bid up local equity prices. But after a point, when the yields on those get bid down closer to safe assets, then it becomes harder to stimulate stock prices.

Stocks become more reliant on economic growth, especially being better than expectations.

Once stocks see their risk premiums get down to low levels, then more money wants to leave the country to seek out higher returns.

One example is the movement of money from Western countries to Eastern countries with higher returns.

This is a long-term theme.

But more money in USD, EUR, JPY, and GBP assets is expected to leave those countries and head more toward Eastern countries where there are higher productivity rate and higher yields can be obtained over time.

If there are higher inflation expectations and yields begin to rise, this can hamper stock prices.

The printing of money is also positive for commodities, holding all else equal.

Commodities can be thought of in a few different ways:

a) a growth-sensitive asset class

b) subject to their own supply and demand functions

c) alternative currencies

Commodities become higher in demand when governments are printing money and issuing lots of debt.

This is because they have a finite supply. They can’t be printed automatically by governments to potentially undermine their value.

They’re of a non-financial character, which adds value because people want alternative stores of value that aren’t going to depreciate like some of their fixed-rate nominal wealth.

Gold is a common commodity that acts more like a store of value than something that’s sensitive to growth outcomes and industrial supply and demand.

Gold is used more like a monetary asset than a traditional commodity with particular consumption uses.

It is essentially a yardstick for the value of money in whatever currency it’s being denominated in.

Yield curve control (YCC) on Currency and Commodity Markets

Yield curve control is an increasingly popular policy in Western countries, given their very high debt-to-income ratios threaten their economic sustainability.

And they have lots of other cash flow-driven liabilities coming at them over the coming decades, related to pensions, healthcare, and other unfunded liabilities.

This will make these countries dependent on very low to negative real interest rates to try keep everything afloat.

What goes along with this is currency depreciation. If holding assets denominated in a particular currency doesn’t help improve real wealth over time, that reduces the demand for it.

For example, if central banks in developed markets target and roughly achieve two percent annual inflation over time, anything less than a two percent return on the cash and bonds is negative in real terms.

Locking in negative real returns for years or decades doesn’t make a lot of sense. And that’s essentially what bonds do if they yield less than expected inflation.

In the US, the national debt and other aforementioned liabilities related to pensions, healthcare, and unfunded obligations adds up to around $300 trillion total.

So, they have to print a lot of money to meet those obligations in nominal terms.

This is not free. Either you get the pressure through higher bond yields or a weaker dollar.

In the short-term, you might get the pain in yields.

This can cause a sell-off in both bonds and stocks. Higher yields cause the discounted present value of cash flows to decrease. That also feeds into the economy, with lower collateral values, lower creditworthiness, lower incomes, and so on.

But after a point, it can get to a point where it’s too painful so it’ll transfer into the currency. Policymakers create money and buy bonds to control yields.

Devaluing the currency is more discreet because it’s not clear who’s paying the price (unlike raising taxes or cutting spending). And it’s less painful than rising credit costs.

From a trader’s perspective, you know you can get either rising yields or a weaker currency. But you don’t necessarily know which one, or what the quantity of the move will be. And the timing is difficult as well.

That means you can have both a short bonds and short dollar trade if you have a long-term perspective. Expressing a short currency trade can be relative to some other currency or it can be relative to something like owning another store of wealth.

This can be gold, precious metals, certain stocks, or other commodities.

In other words, a short currency trade doesn’t necessarily have to be expressed as shorting the currency versus another national currency.

When you create a lot of money and credit, it devalues it. In the process, it causes other types of financial assets to go up.

Yield curve control vs. Quantitative easing

Different policies have different effects on different markets.

YCC is similar to QE because the central bank is printing money to buy bonds and other fixed income securities.

QE is different from YCC in that QE has no specific bond yield target while YCC aims to fix the rate at a certain level or range.

With QE, the central bank will commit to purchasing a certain amount of bonds or securities to support asset prices. This helps lending, with the positive feed-through of lower long-term interest rates into the economy.

Yield curve control has a specific bond yield in mind on one or more parts of the curve. This can be one or more yearly targets.

In normal times, central banks peg the front-end of the curve and let the remainder be dictated by market forces.

Under a YCC regime, they may look to peg one or more mid-duration targets.

For example:

- Japan began controlling its 10-year yield to around a zero percent rate in 2016. Australia has looked to peg its 3-year yield.

- The US, during World War II, pegged multiple rates on the curve to prevent crushing interest costs from all the borrowing needed to deal with the war spending.

In the US World War II YCC regime, the US still had an upward-sloping yield curve.

This incentivized investors to borrow cash and buy longer-term bonds to capture a spread.

Simply put, YCC guarantees a yield while QE merely has an influence on them.

YCC is more bearish for a currency – and more bullish for alternative stores of wealth like commodities – than QE.

YCC is essentially a more forceful policy to ensure that large government deficits can be financed without interest rates increasing.

QE will take a policy approach that commonly works by buying a certain amount of securities per month or within a certain timeframe.

Depending on the effects it has and economic conditions, it will be recalibrated, usually with communications of intentions done ahead of time to minimize market impact.

YCC will operate by coming into the market on an “as needed” basis to buy a certain amount of securities to maintain a specific yield. The central bank may also choose to sell securities should the yield fall below a desired range.

Essentially it’s a fixed quantity (QE) vs. fixed yield (YCC) concept.

YCC is generally a bigger deal for markets.

If interest rates are essentially pegged, that means the expression of that volatility goes through the currency markets.

If currency markets are managed as well, then it ends up in economic volatility, which isn’t desirable.

FX market volatility throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s has been quite low – historically low at times.

But currency traders are increasingly looking toward the potential for higher FX volatility as central banks take more measures to peg interest rates.

Even if you control interest rates, there are still difference in growth, inflation, capital flows, and other barometers of economic activity.

So, traders are likely to increasingly look toward currency markets as a place to trade these forces.

Many policy approaches don’t fit cleanly into one category

Monetary and fiscal policy is complex. There are assumptions baked into markets, and it’s not what happens but rather how things play out relative to the discounted expectations.

Many policy moves have elements of more than one of them and run along a continuum.

For example, if the government provides a tax break, that’s not exactly “helicopter money”. But it could be depending on how it’s being financed.

If the central bank is monetizing the extra fiscal deficit from a tax break, and if the government is distributing the money with the central bank financing that spending without a loan, then that’s helicopter money through fiscal channels.

Money and credit drive markets

Money and credit are what drive markets. Things like valuations can be a motivator for movements of capital to certain market participants.

But the market is a mix of buyers and sellers who are doing that buying and selling for different reasons.

For example, zero percent and negative bond yields don’t make any sense until you understand who is buying and for what reasons. If you looked back over 5,000 years of financial history you would have believed that this type of thing couldn’t happen.

After all, it doesn’t seem to make sense why someone would want to buy a bond that doesn’t give them any income even in nominal terms.

The answer why this is occurring is because central banks are the ones doing the buying to help control economies and they’re price-insensitive.

In doing so, they are also devaluing currencies. If currencies and bonds (i.e., currency delivery over time) don’t yield much and they’re printing more of it, then people want to get out of it.

Monetary and fiscal policy are the two main levers for how money and credit are driven into the financial system and how markets move, so it’s important to understand them.

In the US and practically all of the developed world, we are now in a policy world where interest rates aren’t very exciting to trade because of central bank control over them.

So, to make the system work, fiscal and monetary policy will be better coordinated to get the money and credit in the hands of those who need it to make the system function and to prevent a lot of the social chaos that transpires when it doesn’t work well for a large part of the population.

Fiscal policy has the complications of being a political process. But it has certain advantages that monetary policy doesn’t. Lowering and raising interest rates manages the economy with a very wide brush.

Fiscal policy has the disadvantage of being a political process, so it’s not as easy to decide what the best thing to do is in an expedient way. But it can direct resources in a targeted way.

Coordination with monetary policy involves the central bank coming in to provide the funding and prevent interest rates from going up to avoid offsetting the intended policy objectives.

The new monetary paradigm

The paradigm we’re in now is simply to get money in the hands of the people who most need it to make up for lost income to avoid an elongated depression in economic activity.

That means for most investors in developed countries who are focused on their own domestic markets, cash and most forms of quality bonds are largely not very viable investments from an income perspective.

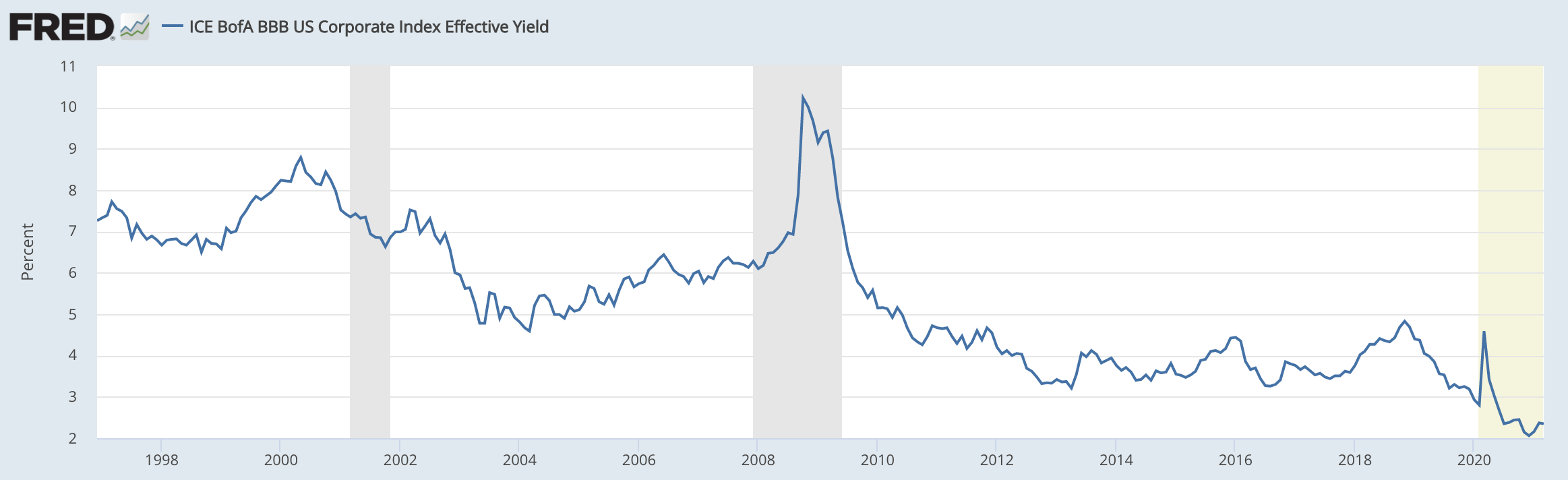

Even the BBB yield, which is one step above junk grade, is only about 2.3 percent.

(Source: Ice Data Indices, LLC)

With a couple percent in nominal yield, after inflation and taxes, you’re left with about nothing or potentially worse than nothing.

Not only that, being this is triple-B, there is material credit risk and mark-to-market losses to potentially deal with.

The zero and near-zero rates across the developed world is probably the single most important issue for investors to understand.

This is essentially what’s driving the new need for stores of value, with a lot of that spilling over into commodities and things like cryptocurrencies. It’s not so much that cryptocurrency is reliable, but rather people want/need a different asset class with everything else being so unattractive.

The old conception of what makes for a good portfolio with both upside and ostensibly balanced risks – e.g., 60/40 between stocks and bonds – is likely going to give pretty disappointing returns.

If stocks are only providing 4-5 percent long term in developed markets – because that’s what low rates in cash and bonds cause – and bonds are only giving 0-3 percent depending on the type, that doesn’t give much.

In nominal terms, a 60/40, if you assume a 5 percent equity return and a 2 percent bond return:

Nominal return = 5% * 0.60 + 2% * 0.40 = 3.8 percent

If inflation is around two percent, that gives not even 2 percent in real returns. Once you pay taxes and if you have transaction costs to deal with it’s even worse.

AQR’s recent estimate for the 60/40 was about 1.4 percent annualized returns in real terms (which would be around 3.4 in nominal terms, taking developed market central bank inflation targets).

The old ways are out

Though most traders have memories that go back to the point where they believe stocks only go up, the zero lower bound on interest rates takes away that traditional reliable tailwind.

The standard ways of easing policy and having that create a boost to asset prices won’t work to the degree we’ve become accustomed to.

It was true in the US, developed European countries, Japan, Canada, and developed Oceania (Australia, New Zealand).

Normally, when there’s a downturn in the economy, the central bank lowers interest rates and there’s a move toward bonds and away from growth commodities and growth-sensitive currencies. That fixed income exposure helps offset some of the losses in equities.

Now that effect is gone because bonds can only go so low in nominal terms.

And stocks run into issues when the rate structure can’t be lowered much, though there’s technically no limit to how high they can go up.

When the returns on stocks are low relative to the risks, then money starts heading into other assets and other countries.

With offshore capital flows, that’s a currency effect.

Returns come from both assets and currency, not only from assets alone.

Depressions don’t last

Depressions don’t last indefinitely. In one form or another policymakers figure out they need more money and credit in the system and will devalue it.

This is irrespective of what type of monetary system they’re on whether that be commodity-based, commodity-linked, or fiat.

If they’re on an constrained, commodity-based or linked monetary system – e.g., gold-based, bimetallic – and changing the convertibility of the commodity for the currency doesn’t work, they inevitably sever the tie with it.

The US had to do this in 1933 and 1971, and has been on a fiat system ever since.

The US has the great privilege of being the world’s top reserve currency.

Depreciations are especially a risk when a currency isn’t in great demand globally, or when a lot of money has been borrowed in a foreign currency, like they commonly do in emerging markets.

This is why there was very little economic support in emerging markets who weren’t able to contain the virus well (e.g., much of Latin America).

The lack of a reserve currency forced them to take the pain through their incomes. Mexico is a popular example, as is Brazil.

But policymakers, at some point, will always want to ease to get a reflation in activity.

Hitting the zero interest rate bound has never genuinely been an absolute constraint even if it seemed like a barrier and a novel problem when it happened.

In the 1930-1932 period in the US during the Great Depression and the 2008-09 period after the financial crisis, the US, in both circumstances, bought financial assets.

This lowered long-term interest rates and created a reflation in commodities, gold, and stocks and weakened the currency.

Even if nominal interest rates can only go to around zero, inflation-adjusted interest rates can go quite negative.

This increases demand for inflation-protected bonds, like TIPS. It’s also why inflation-protected securities tend to correlate more with gold and commodities.

US reflation history

At the depth of the Great Depression, just after inauguration on March 5, 1933, President Roosevelt made the announcement of ending the link with gold and depreciating the currency to reflate the economy.

This measure gave banks the money they needed to repay their depositors.

The same type of thing happened on August 15, 1971. President Nixon got on national TV and said he was unlinking gold from the dollar. This dollar-gold relationship had been re-established in 1944 under the Bretton Woods monetary system.

Like in 1933, there were too many liabilities relative to the amount of gold available and there wasn’t enough gold to go around.

There was the same type of “desperate easing” situation in 2008 with the US Congress and Treasury getting together to create the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

They also went to quantitative easing, similar to the Fed’s buying of Treasury securities in July 1932. This enabled the bottom to finally be reached in the US stock market after an 89 percent slide over 2-1/2 years. There was a 51 percent drop over 19 months from the 2008 crisis.

In 2012, with the debt crisis in Europe among many disjointed countries united through a common currency, ECB President Mario Draghi had a similar type of decision to make.

Timing elements

Bonds usually act first, then currencies follow.

The US dollar is also heavily driven by yields. So if bond yields decline, that means less return on the currency over time. (Bonds are a promise to deliver currency over a period of time.)

At the time, you don’t necessarily know which of these various asset class interactions is going to happen or how it’s going to play out.

Back in 1971, there was a large decline in the value of real stock prices (up in nominal terms, down in real terms). Inflation accelerated. Bonds also did poorly. Gold and commodities performed best.

We’re also now going into an environment where the negative stock-bond correlation won’t hold up as well. Uncertainty in inflation is higher when monetary and fiscal policy are pushing in the same direction.

One potential analogous period to now is the late-1960s entering the 1970s, which set up such a good period for commodities.

Inflation was low, interest rates were low, and fiscal deficits were high due to growing social programs and a war overseas.

Fiscal policy was loose and monetary policy went the same way when the US unilaterally pulled out of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971.

Back then, gold was considered money and USD could be exchanged for a fixed quantity of the yellow metal at $35 per ounce.

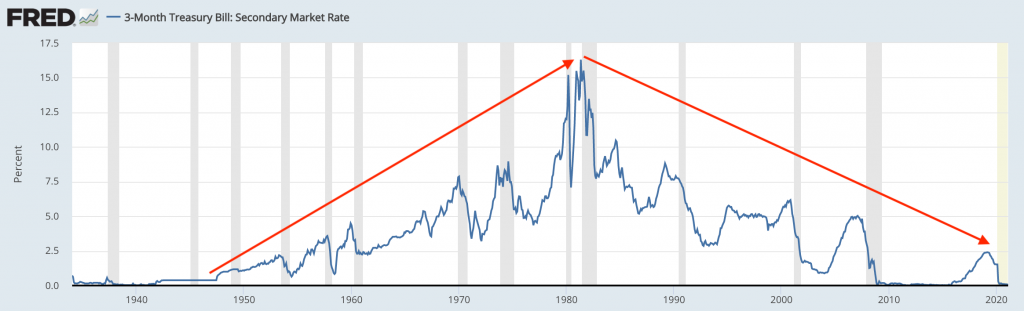

Because of the inflationary 1970s, eventually the Fed had had enough by the early 1980s, who hiked short-term interest rates to over 19 percent. This was more than the inflation rate (in other words, real rates were positive).

This attracted more inflows into the dollar and out of commodities and gold. Bonds were good again and had high nominal returns.

It caused a blip in growth. But this was only temporary, as the Fed eventually eased once inflation was broken.

This easing gave way to the stock and bond bull markets of the 1980s and 90s and more or less the environment up to the early 2020s.

Because of this disinflationary trend, this was great for the present values of financial assets and caused alternative stores of value (e.g., commodities, gold) to fall out of favor.

US Short-Term Interest Rates

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

It’s hard to time these shifts. The general playbook in a reflationary environment is essentially:

– Long certain stocks (companies that don’t rely on interest rate cuts to keep their earnings growing)

– Long commodities and gold

– Short bonds + Short currency

But knowing when to get in and out of this is difficult.

This is why having balance in a portfolio is key.

Cash is one of the worst stores of value

Commodities, gold, precious metals, and certain types of stocks can be good stores of value, as we covered.

Cash is typically thought of as safe, but cash is one of the riskiest investment assets over time.

In this environment where central governments need to create money and finance very large deficits to stay out of a deflationary depression, traders can’t stay in too much cash outside the obvious reasons for having liquidity, a buffer room, and optionality to pick up discounts, as the main ones.

Too much cash can be counterproductive.

When thinking from the store of value concept, cash is not that safe. It doesn’t earn a nominal return. And there’s inflation that causes it to decline over time.

Then there’s also the devaluation aspect when creating a lot of it, which is an issue for foreign investors trying to use the USD as a reserve asset.

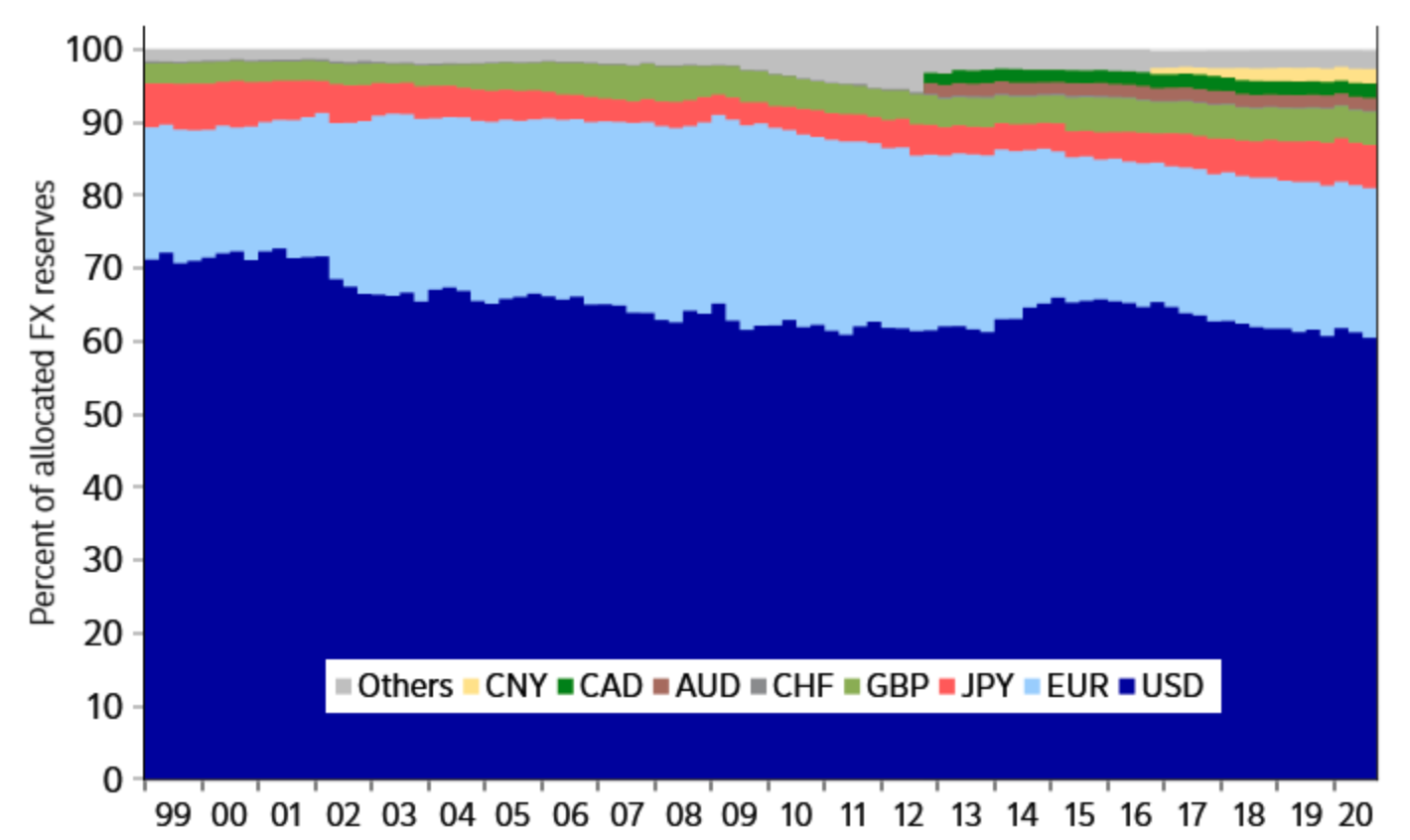

The US dollar will continue to decline as a percentage of reserve, with the Chinese RMB and gold expected to be beneficiaries.

FX reserves by percentage over time

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Many market participants tend to think of just nominal returns. But there has to be some balance in a portfolio.

Looking over history and finding analogous periods to the one we’re in now (e.g., the 1935-1940 period, late-1960s heading into the 1970s, or another), you can’t be sure if you’re actually going to see a depreciation in the value of money (i.e., your own domestic currency).

“Risk” in trading is often defined as capital losses. But risk is broader.

Cash is not a risk-free investment even though its capital losses are negligible over small time horizons – i.e., there’s basically no price volatility.

Cash can be a risky asset because it loses value over time in a less pronounced manner.

So, any trader has to think less about “what’s good” (e.g., what stocks do I pick, what concentrated exposures should I have) and think about different asset classes and different geographies in terms of having a strategic asset allocation mix.

The one thing you can be pretty sure of is that financial assets are going to outperform cash over time.

Central banks, especially in reserve currency countries, are not going to allow a meltdown to occur without printing money and doing what they can to save the system.

Risk assets

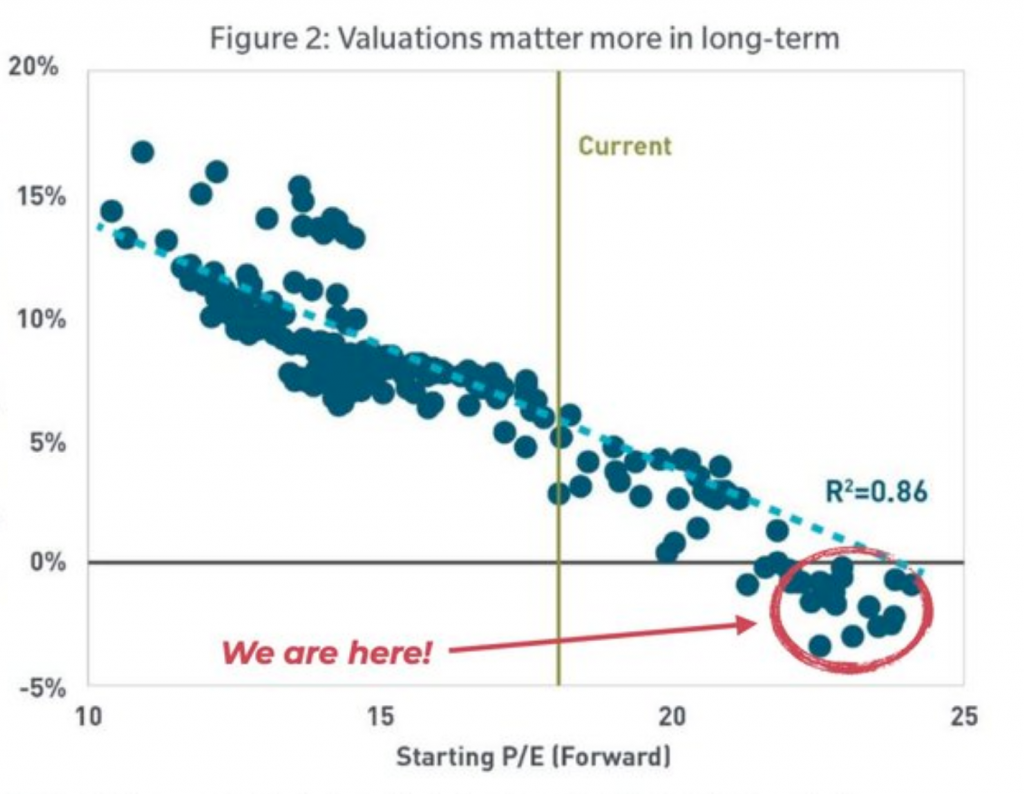

Currency and commodities trading is likely to pick up in popularity not only because of secular macro forces (e.g., interest rate control, emphasis on stores of value), but because of mediocre forthcoming returns in stocks.

The forward returns expectations for risk assets, in real terms, is probably around zero over the next decade with valuations (i.e., earnings multiples) where they are and little interest rate room to stimulate in traditional ways.

Historical Forward P/E Ratios vs. Forward 10-Year Returns

(Source: FactSet market aggregates and S&P Global)

Central bankers won’t want asset prices to be bad in nominal terms because of the necessity to have them be good (e.g., pension obligations).

But the likelihood of them being very good in real terms is quite low. At the same time, traders will have to deal with the volatility of owning those assets.

One of the basic equilibriums in markets is that equities must yield more than bonds, and bonds must yield more than cash.

And they must, by and large, do so by the appropriate risk premiums most of the time.

Cash yields about nothing currently, or negative depending on where you go, and central banks want to keep it that way to incentivize credit creation and limit borrowing costs. There’s essentially a penalty to owning it.

Those currencies will get penalized relative to gold, commodities, and equities over time, as well as higher-yielding currencies in faster-growing countries that are taking more economic share away from slow-growing countries.

Currency and commodities trading complement stocks and bonds, not replace them

In diversifying well, it’s important to be in different asset classes, different countries, different currencies, and in reliable stores of value.

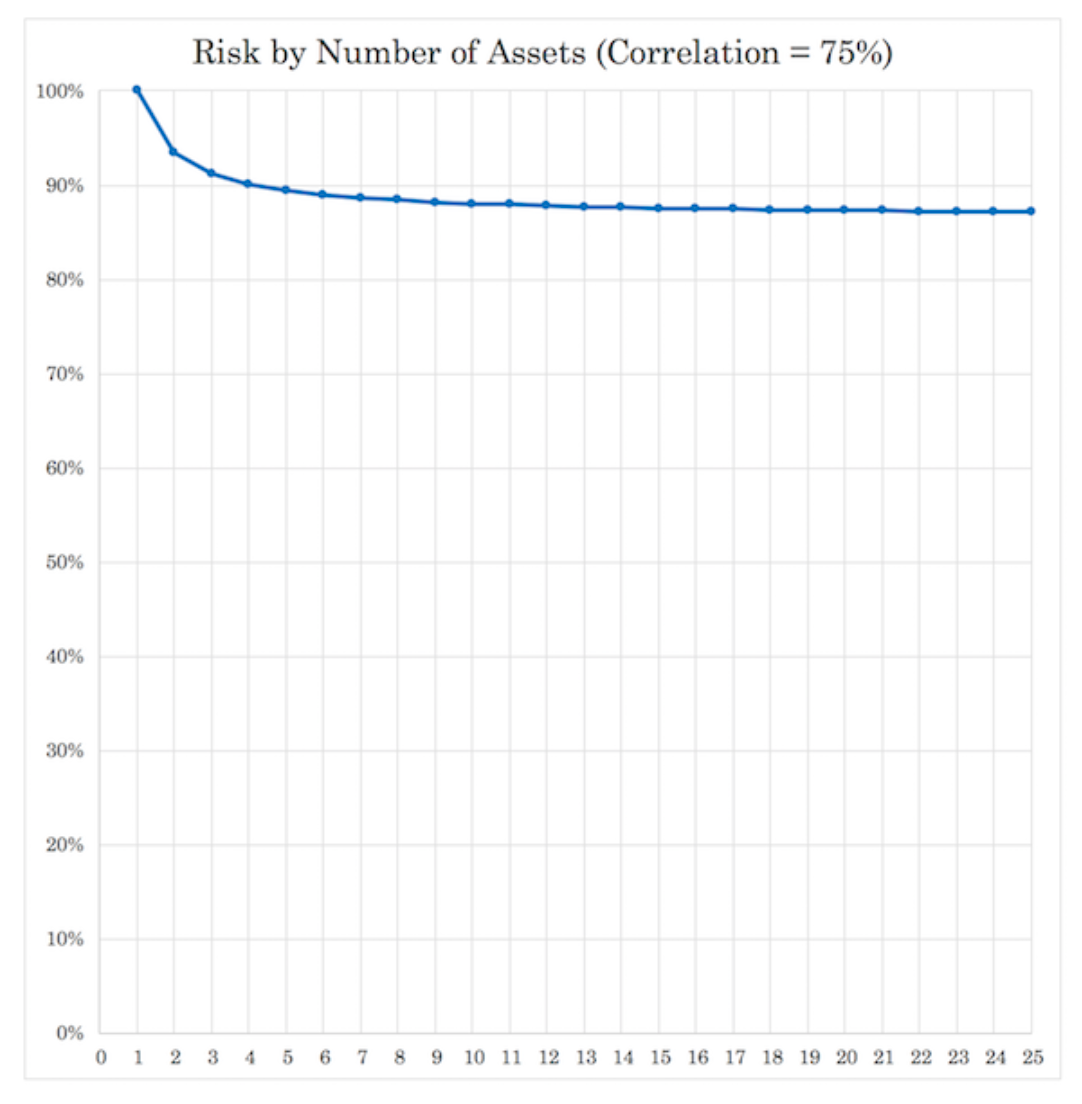

Capital just doesn’t move between different stocks, so choosing stocks isn’t going to diversify your portfolio much beyond a basic level.

If investment assets are about 75 percent correlated (like different stocks), your return to risk ratio doesn’t improve much.

It also doesn’t shift just between stocks and bonds.

It shifts between asset classes, between countries, between currencies, and between different stores of wealth.

If you’re overly concentrated in a certain thing you’re not going to be able to benefit when that wealth moves out in an environment that’s bad for that asset class (and/or the underlying country or currency).

That goes for everything (stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies). Any given asset class is going to drawdown 50 to 80 percent (or more) during the course of one’s lifetime.

If growth underperforms expectations, for instance, that’s bad for equities but generally good for safe bonds.

If you don’t have a portfolio that’s well-diversified to other asset classes, countries, currencies, and wealth store-holds, you won’t have the portfolio to “catch” that movement of liquidity and help efficiently extract risk premia over time.

With a concentrated portfolio, you’ll get some higher highs. But you’ll also get lower lows, higher left-tail risk, longer underwater periods, and higher risk per unit of return.

If you’re only in stocks and/or bonds in your home country and domestic currency, you’re quite poorly diversified even if it’s ostensibly balanced through something like 60/40 (which is more like 90/10 because equities are more volatile).

Having commodities and different currencies diversifies your exposure so you’re not too dependent on any given macroeconomic outcome – particularly growth being above expectation with mild to low inflation for equities.

Because of where interest rates are, you’re dealing with lower-than-normal returns but the same or higher risks going forward.

If you can balance well, you don’t necessarily have to predict shifts ahead of time or move around tactically in the markets.

Growth and inflation are the two big economic forces dictating movements in markets at the top macro level. Now we have the additional influence of interest rates no longer being a tailwind to financial assets or having the ability to be cut to help offset a drops in earnings in financial assets. Currencies are likely to play more of a role in expressing those shifts.

There’s always going to be competition between all assets, countries, and currencies – i.e., between assets in a single sector and asset class, one asset class to another, one country to another, one currency to another, financial to real assets.

Capital and wealth is going to move around.

So, the basic starting point is how to get to a risk-neutral strategic asset allocation and go from there.

When it comes to making tactical bets about what to be long and/or what to be short, most traders should be very cautious about whether they can do that effectively due to transaction costs, competition, and general reality that the expectations are already baked into the price.

So, the risk-neutral “base portfolio” is a good bet to start with.

Final thoughts

Developed markets are in a new monetary paradigm where the adjustment of short-term interest rates and quantitative easing no longer work as well.

This has pushed countries into a process of better unifying fiscal and monetary policy to help get money and credit to where it needs to go.

We also have a very wide distribution in the future path of the economy. It could go anywhere from additional deflationary outcomes (the economy is sitting on a lot of debt) to something like a slow growing economy with higher than normal inflation (stagflation).

Over the past 40+ years, there’s been a disinflationary bias to the point where policymakers have erred on the side of easing.

Geopolitically, the world is going from a level of higher cooperation, integration, and interdependence to one that moves more toward decoupling, self-sufficiency, and less interconnected supply chains.

This could also provide traders and investors additional benefits to diversification given lower correlation across global assets.

The ultimate breaking point comes in terms of unacceptably high inflation and devaluation of the currency.

Potential currency issues may not seem like much of a theme in developed markets, even though the spending patterns in excess of incomes and productivity pose a long-term challenge.

First, to replace the world’s top reserve currency (the US dollar) and the others (euro, yen, pound and a few more), there needs to be a better system first.

Second, currencies are largely floating rate systems, so large devaluations (especially relative to gold), like in 1933 and 1971, are unlikely.

Effective diversification is more important than ever

It’s always important to have assets in your portfolio that can do well when stocks and other “high yield” assets perform poorly as an asset class.

Over the past several decades, you could rely on safe nominal bonds to provide something of an offset, but that’s no longer available.

Certain nominal bonds in emerging markets still have positive yields that could benefit if deflation is still the predominant global outcome.

In China, especially, nominal bonds still tend to do well when stock prices fall. This holds up the relationship that many market participants in the developed markets have become accustomed to over the past several decades, but is now less stable.

Emerging market bonds tend to be under-tapped by global investors. Access can sometimes be an issue.

Inflation-linked bonds, gold, and other precious metals are alternative stores of value and likely to be better than nominal bonds.

Consumer staples, utilities, and other forms of defensive stocks that have stable earnings over time are likely to be more reliable.

Land is a classic inflation-hedge asset and is also a tangible and non-financial in nature.

But land and real estate also depends on its utility and what kind of income can be made from it. Malls and restaurants are different from e-commerce distribution centers.

If more learning is done from a distance then student housing is less valuable as well, even though it traditionally has been somewhat of a recession hedge (more people want to go back to school when the economy is weak).

Farmland and timberland are also a commodity ownership type of investment and provide some diversification benefits.

Things that are off the beaten track, like reinsurance and litigation loans that are less economically sensitive are also of interest in a time like now where diversification is more prized than ever.

Emerging digital assets

Digital assets that can be held privately or semi-privately are increasing in popularity. An online business providing regular income is an asset that’s doing its fundamental purpose.

But digital currencies and cryptocurrencies are still primarily speculative. The main problem now is that the regulatory picture isn’t clear on what will become of these. This holds back institutional adoption, greater liquidity, and lower volatility that will help it become a better store of value.

For most, it’s not clear what many of these alternative cash “coins” are.

Are they stores of value, like a “digital gold”?

If they’re involved in fintech applications, how do they generate productivity to give them value?

Currently, they lack the two (or three) main features of a currency:

a) medium of exchange

b) store of value

c) the government wants to control it

Many are just trying to speculate on the price movement hoping it goes their way. That keeps the volatility high with the rapid turnover common to highly speculative markets.

If bitcoin (as the most popular incumbent) becomes large enough as a “secret” payments system (e.g., for money laundering, financing terrorist activities) will governments allow it to exist?

Gold has been banned because people used it to transact in and store their wealth “off the grid”. Naturally, a central bank or monetary authority wants to have control over all the money and credit within its borders.

All in all…

Having some commodities can be useful to have in a portfolio as stores of value.

Currency diversification is highly undervalued in portfolios, even if that just means 5 to 10 percent in gold and ~5 percent in a diversified commodities basket.

Consumer staples and, to a lesser extent, utilities, will take over more of a role from nominal bonds.

Since they tend to reliably grow their earnings because they simply provide what people need (e.g., food, basic medicine, water, heat) they could serve as a type of fixed income alternative with yields so compressed in fixed income.

However, they will still express more overall volatility than bonds as longer-duration assets.