Inflation-Linked Bonds & TIPS: A Primer

Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) – also commonly called inflation-indexed bonds, inflation-protected bonds, or linkers – are a type of fixed income security where the principal is indexed to the rate of inflation or deflation.

The concept of the inflation-linked bond is not new. People want to own securities that give them a steady stream of income, but also want protection against inflation as well.

If the principal is indexed to the rate of inflation, the one holding an inflation-linked security doesn’t have to worry about the income they derive from it decreasing in real terms.

Inflation-linked bonds have existed in some form since at least the 1700s. The Massachusetts Bay Company issued an inflation-indexed bond in 1780.

The UK government came out with inflation-linked gilts (ILGs) in 1981 and the US government came out with Treasury inflation protected securities (TIPS) in 1997.

However, most fixed income securities are of the traditional nominal rate variety. That creates problems when cash and bond yields no longer generate effective returns, forcing them to look toward alternatives.

The issue of zero percent nominal yields

Central banks in developed markets prefer to run inflation at small positive percentage.

Traditionally they target about two percent per year, with the idea of it being a symmetrical or average target. If bond rates are around zero, that means they are actually worse than useless for increasing your spending power over time.

Investors can still use bonds as a form of wealth preservation and traders can use them as a means to speculate on the future trajectory of interest rates. But the standard use of bonds – income generation – is no longer there.

Because developed market economies have so much debt and other obligations relative to income, bonds are closer to a borrowing vehicle than a traditional investment.

Nominal yields can only go so low – about zero or a little under. After that, it doesn’t change the incentives much for lenders and borrowers to help stimulate credit creation.

Lenders still need to be cautious about who they lend to. And after a point, lower rates are not going to get people into projects and investments that help finance spending the real economy.

The rate of additional returns on a nominal rate bond aren’t much when it already yields about zero.

There’s little price upside and a lot of downside if inflation picks up and real rates were to normalize, for example.

This low yield conundrum on nominal rate bonds also leads to other problems.

Bonds don’t diversify equity risk if they can’t increase in price much.

You also have a low discount rate on earnings that makes the price on virtually all financial assets high. That reduces their future upside. It also makes for a terrible potential drop in the other direction should income fall greatly or interest rates increase.

It also weakens the currency, as fewer people want to hold currency and bonds. Bonds are simply a long-duration fiat flow. They’re a promise to deliver currency over time. If neither cash nor bonds yield much, people will increasingly want to get out of that currency.

Domestic vs. International Bond Traders

There’s also a difference between what domestic investors want and what international investors want when they look at a particular bond market.

Domestic investors care what their real yield is going to be. Namely, what’s the nominal yield on the bond relative to the rate of inflation. The higher the real yield, the better.

Foreign investors care more about the currency. If they invest in a USD-denominated bond instrument, for example, and their domestic currency is in EUR, then they have that exchange rate movement to worry about.

The cost of hedging arrangements also accordingly influences bond yields and relative exchange rates. This is especially true for an international currency like the USD.

An EU-based trader that puts up EUR in exchange for US Treasuries is making a bet that entails:

– the coupon of the bond

– the movement of US interest rates (nominal for a fixed-rate bond, real for an inflation-linked bond)

– the movement in the EUR/USD exchange rate

For a domestic investor, if the nominal yield is so low that it’s less than inflation by some amount, then they know their purchasing power from it will erode over time.

For a foreign investor, if the yield of the bond is low and the US has to create money and issue a lot of debt to deal with its intractable financial issues, then they have to worry about being paid back in devalued currency.

That’s why historically when one country owed other country currency, many times it’s been denominated in gold to prevent them from simply printing what they need in nominal terms (e.g., Germany and its war reparations situation in the 1920s that essentially guaranteed enormous inflation problems).

The case of China and its ownership of US debt

China owns a lot of US bonds, so they’re currently in this conundrum. The bonds don’t yield much and the US is printing money (and will continue to) to relieve its debt situation over time, causing the dollar to devalue.

On top of that, as China rises in influence globally, that creates geopolitical conflict with the US and some European countries. That creates certain tail risks that their debt service payments on US Treasury debt could be suspended if the relationship deteriorates enough.

So China, over time, is going to want to shift away from that debt. They want to buy the assets they know they need.

They’re going to buy assets, currencies, and currency-like alternatives that are tried and true, like gold. They also need oil, being dependent on imports, so they’re going to buy that.

Not only are they going to buy oil and commodities, they are going to buy the commodity producers because there’s only a certain amount of inventory of commodities they can hold.

China’s also going to buy other kinds of companies that can be considered stores of wealth, instead of being exposed to bonds denominated in depreciating dollars.

Moreover, when interest rates are stuck at very low levels in most developed markets, currency volatility must increase unless that spills over into economic volatility.

Interest rates are anchored through very low short-term rates or even longer-term rates through policies like yield curve control (YCC).

When this is the case, currencies become the main channel for trading the relative economic outlooks of different countries.

Demand for inflation-linked bonds

Interest in inflation-linked bonds has increased as interest rates in developed markets have gone to extremely low and, in some cases, negative levels.

This has affected not only cash but also traditional nominal rate bonds.

People want and need alternatives.

They can look at non-fiat stores of wealth like gold, precious metals, and some commodities.

They can look at other currencies and countries that don’t have these low-yield issues. While low yields are representative of the West, they are not typically representative of the East and many other cyclical emerging markets.

They can look toward certain types of stocks that involve selling what people need and pertain to where the economy is going.

There’s also inflation-linked bonds that get rid of this “price cap” on nominal rate bonds (since nominal bond yields can only go so low, unlike real yields). Yields and prices move inversely.

How do inflation-linked bonds work?

Inflation-indexed bonds provide a type of hedge against inflation.

They are tied to the cost of consumer goods as measured by a type of inflation index. The most common gauge is the consumer price index (CPI).

With an inflation-linked bond, the principal (face value or par value) rises with inflation.

Are inflation-linked bonds a good investment?

Like anything, inflation-linked bonds shouldn’t be overemphasized. They can be a piece of a portfolio to hedge against inflation.

They are one alternative to nominal rate bonds. Traditionally inflation is bad for bonds.

If someone is sitting on a pile of regular bonds and inflation runs higher, their bonds will lose a lot of their value in terms of principal and their real purchasing power.

Portfolios should ideally be prudently balanced across a range of asset classes, countries, and currencies.

Who issues inflation-linked bonds?

The US and UK governments are the most prominent issuers of inflation-linked bonds at the sovereign level in the form of TIPS and inflation-linked Gilts (ILGs), respectively.

Many other governments do as well.

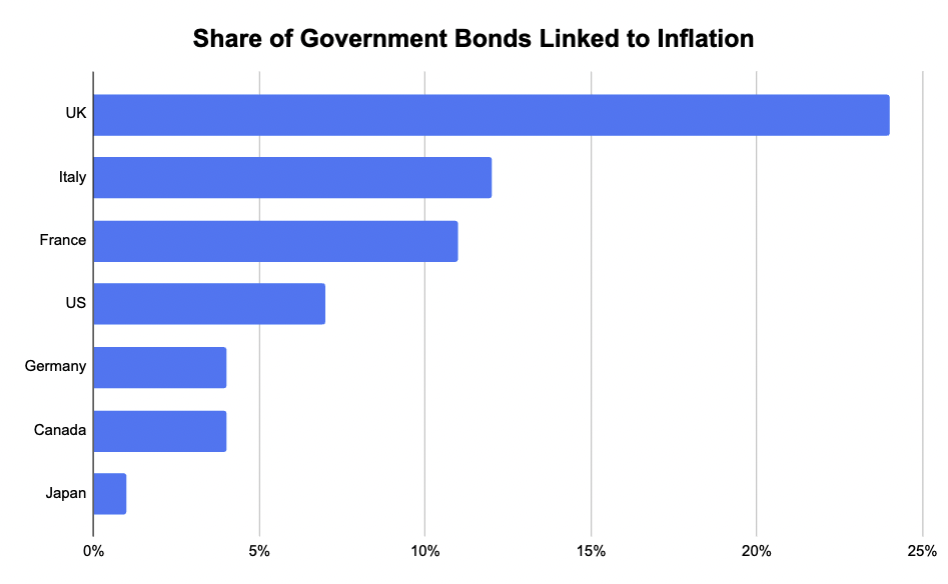

What Governments and Countries Have the Most Inflation-Linked Debt?

The UK has traditionally been the market with the highest percentage of inflation-linked debt at around one-quarter of their sovereign debt pile.

Italy and France are next at just over 10%.

The US has traditionally had 5-10% of its government debt linked to inflation.

Germany and Canada are both at around 5%.

Japan is at about 1%.

Why invest in inflation-linked bonds if inflation is low?

Assets are priced as they are because they discount expectations. What is known is already baked into the price.

Low inflation is already discounted into the price of inflation-index bonds as traders assume that the Fed will be able to control inflation around its approximate two percent mandate.

10-year Breakeven Inflation Rate (inferred from 10-year US TIPS bonds)

30-year Breakeven Inflation Rate

Why do TIPS have a negative yield?

The yield of a TIPS bond is equal to the corresponding Treasury bond yield minus the expected rate of inflation over the duration of the bond.

When Treasury bonds yield less than the rate of inflation, the corresponding TIPS bonds will yield negatively.

If a US Treasury bond yields one percent, and inflation is priced to be two percent, the corresponding TIPS bonds will yield minus-one percent (negative-100bps).

If inflation were to go up to three percent, the return of the TIPS bond would be that minus-one percent plus three percent, or two percent in total.

When a TIPS bond matures, you are paid the adjusted principal or original principal, whichever is greater.

How often do TIPS adjust for inflation?

They are always adjusting for inflation when the market for them is open (8AM to 5PM EST Monday through Friday, excluding holidays).

As inflation expectations shift, so do the prices of TIPS.

Every six months, there are inflation adjustments of a TIPS bond, called semi-annual inflation adjustments.

These are considered taxable income by the IRS for US-based traders. It’s a type of “phantom income” – i.e., you won’t actually see that money until you sell the bond or it reaches maturity.

Some individuals hold TIPS in a tax-deferred retirement account to avoid these tax complications.

What happens to TIPS during deflation?

The principal would be adjusted downward. Moreover, your semi-annual interest payments would be less than if the CPI remained the same or higher.

What advantages do inflation-linked bonds have over normal nominal rate bonds?

While nominal yields have a cap to how low they can go – therefore effectively capping how much price upside they have – real yields don’t.

Inflation-indexed bonds are priced based on real yields, which are the nominal interest rate minus inflation.

The relationship between nominal interest rates (i), real interest rates (r), and inflation (π) is represented by what’s commonly called the Fisher equation (after American economist and statistician Irving Fisher):

i = r + π

Real interest rates can be found by rearranging the equation:

r = i – π

Inflation can go up a lot in excess of nominal rates. Should that transpire, inflation-linked bonds would have their principal adjusted upward.

For a nominal rate bond, higher inflation would expect to dent their value, with traders wanting more compensation to hold them. (The exception is when real rates fall by an equal amount or more.)

Countries with inflation-linked bonds

United States

US TIPS are the most popular internationally, given they’re denominated in USD, the world’s top reserve currency.

United Kingdom

Inflation-Linked Gilts are issued by the UK Debt Management Office and indexed to the Retail Price Index (RPI).

The UK also has retail bonds issued by National Savings and Investments (the NS&I), which are also indexed to the RPI.

France

France has inflation-linked OAT bonds, often called OATi or OAT€i.

OATi is indexed to the France CPI (excluding tobacco). OAT€I is indexed to the EU HICP index (also excluding tobacco).

Germany

Germany issues the iBund and iBobl.

These are indexed the same as the OAT€I to EU HICP excluding tobacco.

Italy and Greece

Italy and Greece also offer €i bonds, indexed to EU HICP excluding tobacco.

Italy also released domestic retail inflation-indexed bonds (BTP Italia), indexed to Italy’s CPI excluding tobacco.

Spain

Spain has inflation-linked bonds – fully named: Bonos indexados del Estado and Obligaciones indexadas del Estado.

These are also linked to the same index as other EU countries, EU HICP excluding tobacco.

Sweden

Sweden has inflation-linked treasury bonds indexed to Sweden’s CPI.

Japan

Japan has its inflation-linked JGBi.

It’s indexed to its national CPI excluding fresh food prices (a type of core inflation reading).

Canada

Canada issues what they call a Real Return Bond (RRB).

It’s indexed to the Canada All-Items CPI.

Australia

Australia issues Capital Indexed Bonds.

These are indexed to an inflation gauge that takes the weighted average of the eight capital cities.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong releases domestic retail inflation-indexed bonds, called the iBond.

They are linked to the city-state’s composite consumer price index (CCPI).

Russia

Russia issues federal loan bonds (GKO-OFZ).

They are indexed to Russia’s CPI.

India

India issues what they straightforwardly call Inflation Indexed Bonds.

Their principal adjusts upward or downward based on the country’s CPI.

(India has traditionally relied on a wholesale price index (WPI) to measure inflation, which measures price fluctuations of wholesale goods instead of pricing at the consumer level. However, India has more recently adopted a consumer price index (CPI), which is also more prevalent in the rest of the world as well.)

Israel

Israel’s Ministry of Finance issues index-linked treasury bonds, linked to the country’s CPI.

Latin America

Mexico and a few countries in Latin America also issue inflation-indexed bonds.

Their inflation gauges also go by different terms, but are essentially some form of a consumer price index.

Mexico

Mexico has Udibonos, indexed to UDIs.

Brazil

Brazil issues Notas do Tesouro Nacional: Série B and C. Série B is indexed to a gauge called IPCA. Série B is gauged to IGP-M.

Argentina

Argentina has what’s called Bonos CER. The CER stands for Coeficiente de Estabilización de Referencia (Reference Stabilization Coefficient, or essentially indexing).

It’s linked to their INDEC IPC gauge.

Colombia

Colombia issues COLTES, indexed to CPI through UVR (a type of real value approximation).

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Inflation-Linked Bonds vs. Nominal Bonds

Inflation-linked bonds are designed to reduce sensitivity to interest rate changes compared to nominal bonds.

But they don’t eliminate it entirely.

Their primary feature is to offer protection against inflation, as their principal and interest payments are adjusted based on inflation rates.

The extent to which inflation-linked bonds reduce interest rate sensitivity can be understood through two key aspects:

Inflation Adjustment

The principal of an inflation-linked bond increases with inflation.

This feature helps protect the real value of the investment.

When inflation rises, the principal value and the interest payments (which are a percentage of the principal) increase.

This offsets some of the negative impact of rising interest rates that often accompanies inflation.

Duration

The duration of inflation-linked bonds typically changes with inflation expectations.

When inflation expectations rise, the duration (a measure of interest rate sensitivity) can decrease because the increased interest payments shorten the effective maturity of the bond.

This can make inflation-linked bonds less sensitive to interest rate changes compared to nominal bonds with a similar nominal duration.

Inflation-Linked Bonds Still Have Interest Rate Risk

Inflation-linked bonds can still be affected by changes in real interest rates (interest rates adjusted for inflation).

If real interest rates rise, the value of inflation-linked bonds can decline, similar to nominal bonds.

The reduction in interest rate sensitivity is therefore relative and depends on:

- the specific characteristics of the bond, including its

- duration

- the inflation environment, and

- the behavior of real interest rates

As with any investment or trading instrument, the performance of inflation-linked bonds can be influenced by a variety of economic and market factors.

Conclusion

Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) are seeing greater demand by traders and investors as an alternative to low-yielding nominal rate bonds.

Increasingly, many market participants are going to want to get out of nominal rate bonds for various reasons.

There’s the no yield aspect (often negative in real terms).

And there are the elements of diminished risk diversification and the risk of being paid back in depreciating currency when interest rates are so low and people lose interest in holding the currency. (Bonds are a promise to deliver currency over time.)

While investors traditionally look to other inflation storeholds like gold, precious metals, some commodities, and some equities, and other places where nominal bonds still have respectable returns, inflation-linked bonds can become an increasing part of this allocation.

Increasing one’s allocation to inflation-linked bonds and some or all of these and other alternatives are expected to become an increasing trend going forward.

Investors will look to prudently diversify to a unique set of forward-looking risks and challenges associated with traditional nominal rate bond investments.