The Last 500 Years of Financial History & Lessons for Today’s Portfolios

The rises and declines of empires is important to understand because we’re in the middle of a big shift going on currently. Studying how these have worked is important in terms of understanding how it impacts capital flows, and the risks and attractiveness of different assets, asset classes, currencies, and different countries.

Below we’ve distilled the last 500 years of global and financial history down into a few thousand words. At the end, we’ll cover what it means for allocating capital today.

The Rise and Decline of the Dutch Empire and the Dutch Guilder

During the 16th century (1500-1600), the Spanish empire was the most powerful economic and financial empire in the “West” while the Ming Dynasty in China was the top empire in the “East”.

In relative standing, the Ming Dynasty was more powerful overall than the Spanish empire. But the world was not yet globalized like it is today. It was not logistically, technologically, or economically feasible to traverse continents until the late-1400s and 1500s (and not very common until the 1600s), so each had its own sphere of influence.

The Spanish had a strong military and developed a large fleet of ships. They took these ships all over the world to take over new areas of land and extract value out of them.

This included things like gold and silver that had intrinsic value and were considered money. Many countries used a gold or bimetallic standard.

The Spanish empire eventually overextended itself, as all empires do. Expenses rose above the revenue they took in and their relative power waned as other countries became more competitive.

During this time, the Dutch empire gained power. The area of land that we now call the Netherlands was controlled by Spain in most of the 1500s.

As the Dutch became powerful enough, they sought to throw out Spanish rule. They eventually did in 1581. The failure of Spain to invade England in May of 1588 with the Spanish Armada was another sign of the empire’s ongoing decline.

The Dutch eventually surpassed the strength of the Spanish empire and the Chinese in the 1620s. The empire reached its peak power in around 1650.

During this time, the Dutch enjoyed great advantages. Their ships could travel all over the world to capture new lands and resources.

The Dutch had a free-market economic system and Amsterdam became the leading financial center globally. Their shipbuilding and economic strength led to the world’s most dominant military, which in turn was used to help protect their shipping routes and build their empire.

They remained the strongest empire globally for over 150 years until their collapse in 1780.

How did the Dutch become so powerful?

Education tends to lead to dominance in everything else.

Without education it’s unlikely that an empire will come up with new inventions and new technologies that will go on to provide them economic rewards and sophistication in everything else that makes for a productive society (e.g., capital markets, military).

About one-quarter of all of the world’s inventions came from the Dutch in the 1600s.

Ships were the most important. With the military strength they acquired from fighting in Europe and the capabilities of their shipbuilders, they could go practically anywhere in the world and have success collecting new land and valuables.

The capitalist system they had developed helped facilitate these endeavors.

This pertained to not only “capitalism” in the sense of resource allocation, where rewards were tied to incentives to be inventive and create value, but also the invention of modern-day capitalist practices.

Things like trade, production, private ownership, and property rights had existed before. But the Dutch facilitated the ability for large numbers of people to collectively lend money and buy ownership in profit-making enterprises and endeavors.

This initially came from the first publicly listed company – the Dutch East India Company – and the creation of the first stock exchange in 1602. This created the first lending system where credit could be more easily created.

The Dutch guilder also became the world’s first national reserve currency. (Gold and silver had already been considered reserve currencies for thousands of years – i.e., something practically everybody considered having value and wanted to save and often transact in.)

This was because the Dutch were the first empire to truly globalize their presence. This led to its currency being accepted broadly. Dutch capital markets were the best place to be globally.

Their market innovations and success in producing profits attracted additional investors to Amsterdam. The Dutch government took the money that came in and put it into debt and equity investments into various enterprises. The Dutch East India Company was the most important among these.

Because of these qualities, the Dutch empire grew on a relative basis until around the start of the 18th century. At this point, the British started gaining. Others also became more competitive.

When others grow in power and become more competitive (e.g., cheaper workers, knowledge catch-up), the Dutch empire became less competitive and costlier to maintain.

As this happens, maintaining the profitability of the empire so it can continue to grow and produce more than it consumes becomes more challenging. And it’s very difficult to reverse as debts have built up and it’s not easy to get productivity rates up.

The British became the main rival of the Dutch. They grew economically and militarily during the 1700s.

The Dutch and English had more conflicts over economic issues. For instance, British law was created that asserted only English ships could be used to bring goods into England.

The Dutch shipping business was large at the time. A key component was importing goods into England.

Because the British naturally wanted this business for themselves, they would actively seize Dutch ships to enforce this law and expand the British East India Company.

The two had been allies militarily for most of the century or so leading up to Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784). But this relationship began to fray as they would increasingly compete in the same markets.

Like in later history, the 1920s were a period of great advancements and new technologies. This became extrapolated and a debt and asset bubble emerged. When it popped later that decade, there was great economic harm and suffering throughout the world.

The 1930s were a period where there were lots of conflicts over trade and economic issues, technology, capital, and geopolitics where several powers became comparable in capabilities.

As a result, they looked to challenge each other and test what they could do.

There was the case of Germany coming up to challenge the fading British empire and rising American empire in the West. In the East, Japan was gaining on these Western powers and felt it could challenge the Americans if they had to split resources between fighting itself (Japan) and a war over in Europe.

When the British came up to increasingly challenge the Dutch up through the mid-1700s, they came up with new military weaponry and brought more seaborne capabilities to challenge the powerful Dutch naval fleet.

At the same time, they kept improving on the Dutch in relative economic power.

Right around 1750, the British usurped the Dutch in relative power, particularly economically and militarily. The Dutch became weaker as the empire’s expenses grew relative to its revenue.

The British grew more competitive, as did the French.

As is the classic issue, the Dutch became further indebted. This coincided with more internal conflicts over how to divide political power and wealth. Even if there is no outright mention that an empire is in relative decline, it can be observed through various conflicts.

Most commonly there is more fighting between:

- political factions

- those who have wealth and those who don’t (between “capitalists” and “workers”, “haves” and “have-nots”), and

- different parts of the country that may have competing interests (cities, states, provinces)

Moreover, the Dutch’s military was weakened both due to funding constraints and because its relative power had diminished.

As the Dutch became weak and more internally divided, that made them more prone to being attacked externally.

So typically, the rising power will come up to challenge the existing power and various types of wars/conflicts will emerge with respect to:

- trade

- economics

- capital

- technology

- geopolitics…

…before eventually engaging in a military war.

The British measures against the Dutch shipping business hurt the latter across various countries. Other countries, including France, used it as a way to take more shipping business from the Dutch.

This conflict culminated in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War from 1780 to 1784, which overlapped with the British engagement in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

Despite multiple ongoing conflicts, the British easily beat the Dutch both on economic and military fronts.

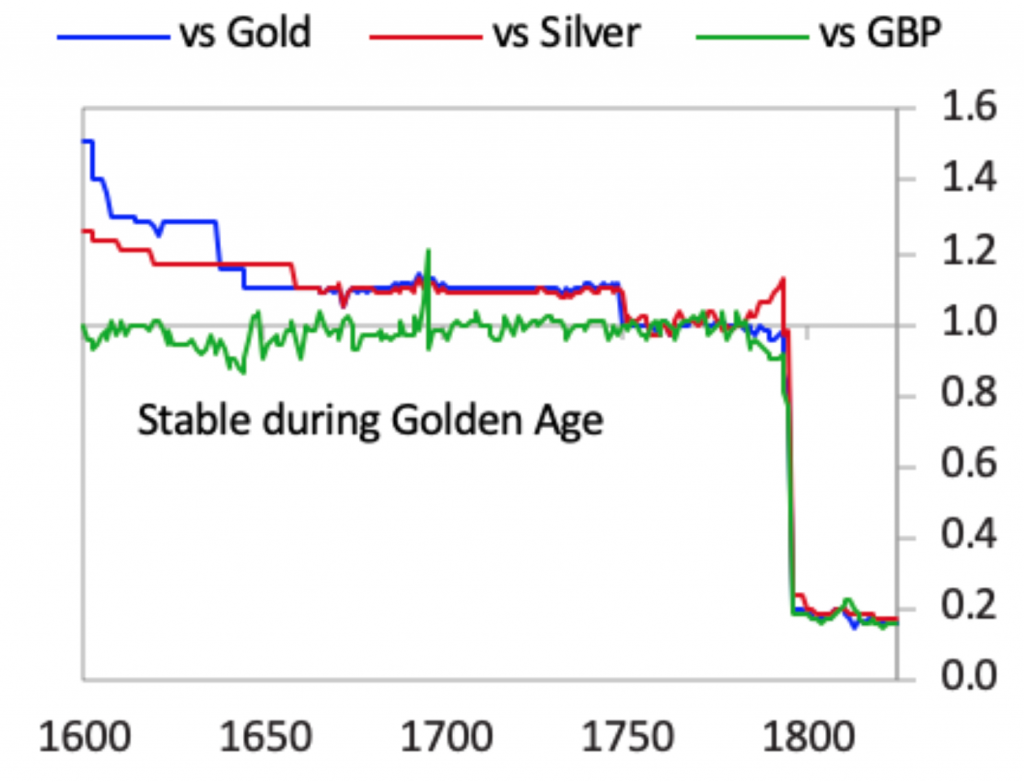

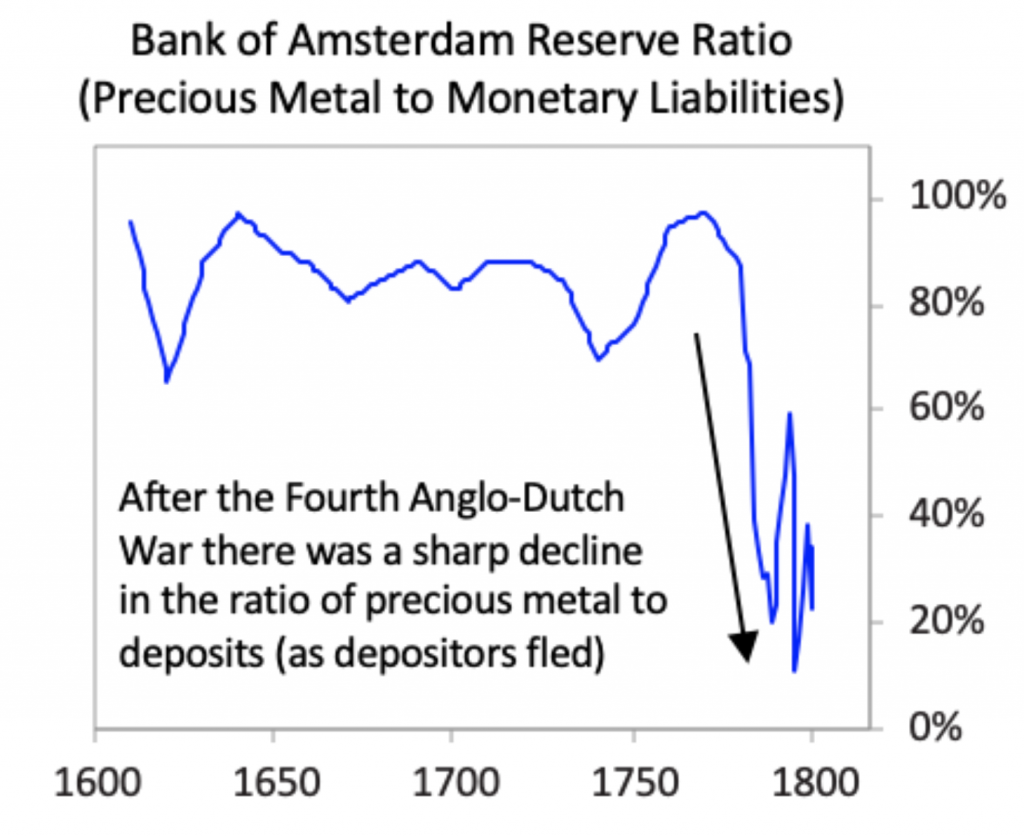

The expense incurred from the war bankrupted the Dutch. It caused the collapse of Dutch debt and equity markets, as well as the value of the Dutch guilder, as illustrated in the following diagram versus gold, silver, and the British pound (GBP).

Precious metals reserves also fell precipitously as depositors got out.

During the late 1700s in Europe, there was lots of fighting within countries and between countries.

When the British defeated the Dutch, Great Britain and its main allies (Prussia, Russia, and Austria) continued to fight the French, who were led by Napoleon Bonaparte in what are known today as the Napoleonic Wars.

These began just after the 1789 start of the French Revolution (in 1792) and went on until the British and its allies defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. This left the British empire as the undisputed top power globally.

The Rise and Decline of the British Empire and the British Pound

After the fall of the Dutch, the British and its main allies (Russia, Prussia, and Austria) got to decide the rules of the new global order during the Congress of Vienna.

The results of that meeting – the Treaty of Paris – enabled them to decide how the monetary and debt systems would work and dictate geopolitical influence.

Great Britain embarked on its “imperial century” where it became the world’s clear leading power.

The pound sterling became the world’s leading reserve currency and the 19th century through the early 20th century was largely a new period of peace and prosperity.

Great Britain was strong enough to be virtually unchallengeable. And because the system worked so well there was little desire to change that.

Everything was not perfect. There were recessions or things that were then called “panics” (e.g., 1825 in the UK; 1837, 1873, 1893 in the US).

The Crimean War was also a military engagement that put Russia against the Ottoman empire and other European allies. But these conflicts were not material enough to change the overarching picture of the period of peace and improving living standards across most of the continent.

The British built strong debt and equity markets much like the Dutch to help incentivize people to pursue economic rewards and finance productive ventures.

Combining this with military strength enabled the British to pursue many of the same types of ventures that also made the Dutch very wealthy and powerful globally.

The British East India Company replaced the Dutch equivalent as the most powerful company globally. The company itself had its own military force that was at one point far more powerful than the British government’s own conventional forces.

This made the stakeholders in the company very rich and benefited the British people greatly.

Moreover, just past the midway point of the 18th century, British living standards accelerated due to the Industrial Revolution. Machines took over more production from humans. This created more goods in a cost-efficient way.

The British were able to take advantages from its competitiveness, inventiveness, economic system, and shipping capabilities (and being on the forefront of other technologies at the time) to go global. It also had a great military to fend off physical challenges.

London replaced Amsterdam as the world’s leading financial center and created new financial products to fund lending and investment initiatives.

The Second Industrial Revolution commenced around 1870 and went into the early 20th century.

New technologies and the new products and services that came out of them improved living standards and productive output. They created wealth for those who invented, owned, and developed them.

The British pound became the world’s top reserve currency through the advantages conveyed from their strength in education, technologies, competitiveness, economic output, global trade, military, and capital markets.

Like the British did to the Dutch, other countries copied the UK during this period.

Its technologies and strategies were duplicated elsewhere and other countries could do what the British did more cheaply (because their workers were cheaper).

This is analogous to US companies locating production overseas because US workers are expensive and other countries will do the work more cheaply.

British technologies were great for those who created, developed, and owned them, but disadvantaged those who were replaced by them.

For example, the modern term “Luddite” (someone against technology or new methods of working) initially referred to the group of people who were protesting the adoption of the mechanical looms that displaced them in early-19th century English cotton and wool mills.

While new technologies are great for the whole, they threaten many of the jobs held by lower-skilled workers. This leads to wealth gaps and more internal conflict.

By the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century, many other countries started becoming more competitive as well.

This period – known as the Gilded Age in the United States – saw the development of the automobile, electricity and its various applications (light bulbs, phonograph), new communication methods (telephone), and steel production.

The United States, which valued individualism, innovation, and competition, grew to become a leading global power during this time. It also began to take over new swaths of land globally and the country itself was already very large and resource-rich.

Great Britain became more indulgent during the Victorian period, as is typical when a leading power achieves high living standards.

More people want to enjoy the fruits of this success while other countries copy them, evolve, and chip away at their advantages.

The tremendous benefits afforded by the reserve currency leads to the empire becoming progressively more indebted because they can borrow inexpensively. More emphasis is placed on indulgences rather than things that will continue to make them more productive.

As other countries became more competitive, the British empire got more expensive to maintain and less profitable.

Other European countries and the US got better economically and had improving militaries.

By the turn of the century, c. 1900, the US became comparable to the UK economically and militarily.

However, the UK still had stronger trade, geopolitical influence, and the world’s top reserve currency. But the US progressively started gaining on these as well.

From 1900 to the start of World War I in 1914, internal conflict grew in the UK.

Because of the wealth gaps that had developed from their technological and economic improvements, there were greater arguments over how wealth and power should be divided.

And because other countries were improving, there became greater challenges to the status quo of the English controlling the continent and global order.

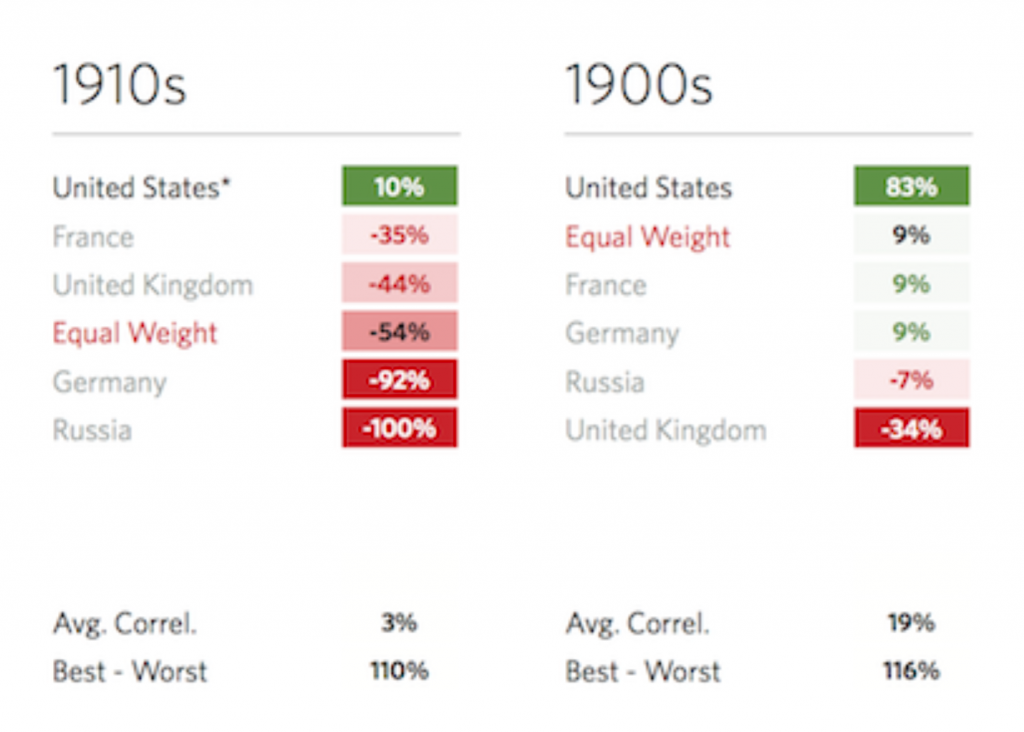

In the 1900s, UK equity markets did poorly, dropping 34 percent. The US, on the ascent, gained 83 percent.

During the 1910s, a period of great global conflict, only the US ended the decade in the green, up 10 percent. The UK lost another 44 percent. Germany and Russia, which would later lose World War I, were virtually wiped out.

As is common during these times, alliances formed throughout Europe and globally (e.g., the UK and the US) and eventually led to an international conflict.

Alliances are largely built based on considerations related to money, resources, and relative power.

In today’s world, Russia and China might be considered complementary allies because one has natural resources and nuclear power comparable to the US (Russia) while the other has the largest share of global trade and economic and capital market development closest to the US (China).

It is common for powers in conflict with each other to want to freeze out each other’s access to capital within their borders.

For example, in the late 19th century, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (who ruled from 1871 to 1890) didn’t want Russia, a country Germany was at odds with, to sell its bonds in Berlin. Instead, Russia sold them in Paris, which helped tighten ties between France and Russia.

Russia had its own internal struggles over wealth gaps and power, which led to a revolution in 1917 and its inability to keep fighting in WWI.

Shipping conflicts, which had gone back to Spain and Dutch and later the Dutch and English, also came into the fray when Germany began rising in power in the late 19th century and into the 20th century.

Germany sank merchant ships going into England during the early days of WWI. These actions brought the US into the war.

The various storylines, and conflicts within and between countries leading up to WWI are numerous and widely debated among historians, so they are beyond the scope of this article.

But WWI, truly the first world war because it involved countries from all over as the world had become global, went from 1914 to 1918. Close to 9 million soldiers died as did around 13 million civilians.

Moreover, as the war went into its final stages, the Spanish flu emerged, which killed anywhere from 20 to 50 million people over 1-2 years.

So the relative peace and prosperity that came out of the British becoming the undisputed leading power in the 19th century gave way as the 20th century came around. The decline of the UK and the rise of other powers led to the emergence of new conflicts.

WWI became a watershed moment for the economic, political, and cultural climate of the world.

While Britain was among the Big Four from the Allied Powers side that won the war (along with France, the US, and Italy), it was clear that the UK’s status as the world’s top power had officially ended.

The Rise of the US Empire and the US Dollar

As is the case in the ending of all wars, the preeminent winning powers get to impose their terms on the defeated powers.

This came into focus during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference where a series of treaties were signed over six months. The Treaty of Versailles with Germany became the most notable.

As a result of the Central Powers’ defeat, the German, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian Empires no longer existed in their current forms.

These empires were divided into new states from what was left of them.

The League of Nations was formed during the peace conference as a way to promote pacifism and work toward preventing future conflicts. Of course, a second world war would follow just twenty years later and cause the unraveling of the League of Nations and lead to its replacement the United Nations.

The losing empires were placed under the control of the winning powers and were put deeply into debt to pay back the winning countries’ war costs.

To prevent the losing powers from simply paying it back in devalued money, these debts were to be paid in gold.

The US at this point was clearly recognized as one of the world’s top powers. Accordingly, it played a clear role in how the ensuing “world order” was set up.

The term “new world order” was referenced by US President Woodrow Wilson as it pertained to the vision of how countries should operate under a global governance system while in pursuit of their collective interests. (As mentioned, the resultant system, the League of Nations, did not work.)

After WWI, Britain continued to expand and oversee its colonies while the US chose to be more isolationist.

The global monetary system after the war was still being worked out. Most countries wanted to go back to a gold standard. However, currencies didn’t become stable against gold until after they were significantly devalued.

Most countries suffered large bouts of inflation. The losing powers, because their debts were to be paid in hard money (gold) that they couldn’t print out of, it was virtually guaranteed they would suffer bad inflation problems.

Germany’s case was the most well-known historically. Weimar Germany suffered horrible inflation in 1923 forward that transpired into hyperinflation.

The wiping out of this debt eventually enabled Germany’s economic and military recovery.

Elsewhere, the 1920s became a period of peace and prosperity elsewhere, with advances in living standards in most other places and increasing trends toward modern styles of consumption.

During the 1920s, the US increasingly developed its debt and capital markets to improve capital allocation and channel debt and investments into various enterprises.

The US’s power led to New York becoming an increasingly influential financial center, rivaling London.

During the period between World War I and World War II, other countries became more competitive and challenged the leading powers.

Germany was most influential in Europe while Japan was most influential in Asia. Both gained on the UK, though the latter remained stronger than both.

The US continued to gain economically and militarily. At the same time, the US was more isolationist and didn’t have a big sprawling empire past its own borders.

As a result, it wasn’t as easy to sweep the US into the new conflict that was brewing.

As normally happens, the period of prosperity in the 1920s led to more debt and greater wealth gaps.

This debt bubble that built up in the 1920-29 period led to a burst in 1929. The classic monetary policy problem of not being able to lower interest rates below zero came into focus during this time.

The depression of the early 1930s was long and severe due to the holdout of necessary supports.

Policymakers also didn’t initially have a good understanding of the type of problem they were facing because the credit crunch at the end of the 1920s was so different from the previous recessions (“panics”) that had happened in their lifetimes – e.g., 1893, 1901, 1907, 1920.

Finally, in 1933, policymakers were able to get a bottom in the capital markets then the economy after doing what’s known today as “quantitative easing” (buying mostly bonds) and devaluing the currency.

This was a global problem, so many currencies were devalued.

This came with more internal disputes and external conflicts over power and wealth in the 1930s.

Sometimes even entire systems are destroyed. In the US and the UK, there were wealth redistributions and changes in political power, but democracy and their capitalist economic approaches were maintained.

However, in Japan, Germany, Spain, and Italy went to more authoritarian approaches. Russia was also authoritarian at the time and had an influence in Europe.

China, while it has been strong for most of its history, was weak in the 1930s. Japan increasingly controlled it.

Japan was undertaking its own efforts to boost its military and expand its influence beyond its borders as a small island nation.

The German and Japanese efforts to expand its territory in the early- to mid-1930s led to wars by the late-1930s. These, of course, led to World War II, which concluded in 1945.

Before all-out military wars there was – like in previous shifts in the world order we covered earlier – about a decade of other types of conflicts pertaining to:

- Trade (usually the first domino to fall)

- Economics and capital

- Technology

- Geopolitical

These practically always occur when powers that have various disagreements and conflicts approach comparability. There are various tests and forms of intimidation that go on.

1939 is known as the official start of the war in Europe and 1941 as the start in the Pacific. But the conflicts that underpinned everything really started about a decade before that as all these conflicts led up to the hot war.

Germany and Japan’s desire to expand beyond their homelands and their natural instinct to want more economic and military power led to them increasingly competing with the US, UK, and France for resources and geopolitical influence globally.

World War II was won by those who had invented new technologies. The atomic bomb was the most important, but it was one of many new weapons that were created that didn’t exist in the previous world war just 2-3 decades earlier.

Around 73 million are believed to have died over the course of World War II counting from 1937 through 1945, with around 24 million military deaths and around 49 million civilian deaths.

While practically no one living in the “Roaring ‘20s” could have imagined what would come next, the 1930-1945 period of depression and war represented a bad time for the world overall.

The Rise of the US Empire and US Dollar after World War II

After the war, “the Allies” (the US, UK, Russia, and to a lesser extent the Republic of China) imposed their terms on the losing parties.

There were several meetings that would shape the post-1945 order to carve up the countries, areas of influence, and the new money and credit system.

The most notable ones included:

- Bretton Woods Conference (July 1944)

- Yalta Conference (February 1945)

- Potsdam Conference (July-August 1945)

The US was put in control over various countries that had a capitalism and democracy mix. Russia was put in charge of those that were communist and autocratically controlled. Each had its own monetary systems.

Germany was split into West and East Germany. The US, UK, and France controlled the western portion. Russia controlled the eastern part.

Japan was controlled by the US.

China, while technically part of the winning side, had significant internal turmoil. Most of this fighting had to do with how to divide wealth between the Nationalists (the capitalist side) and the communists.

While the US had been isolationist following World War I, it took the mantle of the world’s undisputed top power following World War II. This came with economic, military, and geopolitical responsibility.

Under the Bretton Woods agreement, the US dollar was installed as the world’s top reserve currency and was linked to gold. The US had around two-thirds of the world’s gold reserves by the end of the war.

Gold was considered money and money could be exchanged for gold. One ounce was $35. This held until the termination of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971.

The US followed more of a bottom-up capitalist system. US culture prizes the individual and regulations on economic activity were fairly modest.

Most other currencies were tied to the US dollar. A pegged currency system can be difficult to maintain when the economic fundamentals of different countries are very different.

However, during the post-war period, capital flows between countries were not near the proportions they are today. So the system was not in danger of breaking.

USD reserve status has lasted until today given the US has remained stronger economically and militarily than any other country.

Countries like Russia and surrounding countries that were brought in to form the Soviet Union had communist economies.

The lack of incentives and the inability to turn ideas into output significantly held back their economic potential. So this system eventually couldn’t go on any longer and broke down in 1991.

The losing countries following WWI were saddled with large war debts. However, the losing countries following WWII were put under US control and received significant financial assistance through the Marshall Plan.

During this time, the losing countries saw their currencies and debts virtually wiped out, which was terrible for those holding them.

The UK was heavily in debt after WWII and had to borrow a lot from its poorer colonies to fund its war efforts. This meant Great Britain’s colonial expansion era was practically over.

The empire they had built was not profitable to maintain. This led to a decline in Great Britain’s relative power and influence globally.

The British pound was no longer the top reserve currency. Today the GBP is still somewhat of a reserve currency at about five percent of all global savings and transactions. But this is largely due to historical reasons rather than the fundamentals of its currency.

The US and its allies followed the approach to resource allocation that the Dutch and British empires did before them.

Capitalism was prized as the best way to grow an economy and overall living standards. Democracy continued to be a key element of the US system.

New York surpassed London as the world’s top financial center. A new debt cycle began and US markets have performed most everywhere else since.

As is typically the case, the 1945-1970 period produced debt growth that was productive and rewarding for both borrowers and lenders. This was essential for financing innovation and economic development.

But during the 1960s and into the 1970s the US began to persistently outspend relative to the revenue it was taking in.

War and defense expenditures and programs for domestic support – then commonly called “guns and butter” – grew significantly.

The 1960s saw the Vietnam War and the “war on poverty” in the US.

This indebtedness, which also occurred in other countries, necessitated large currency devaluations.

By August 1971, the US could no longer afford to keep the dollar pegged to gold. The level of liabilities that had stacked up meant a hard money system would eventually fail. Gold reserves were shrinking.

Shrewd people back then figured out what was going on and realized that the fair price of gold was much higher than the $35 per ounce convertibility and the dollar’s link to gold would eventually be severed. So they began cashing in more dollars for gold.

The US eventually unilaterally broke the link given the level of claims on gold relative to the actual availability of gold. It was essentially like defaulting on a promise.

Money was no longer gold. Money was moved to a fiat system around the world.

Fiat money served its purpose as a medium of exchange and store of value, but it no longer had any intrinsic value.

Italy and the UK had devalued their currencies before that.

Because fiat monetary systems no longer have constraints to money and credit creation, this led to a big surge in dollar money and debt creation.

A lot of this went into goods and services, which lasted until the 1980-82 period when the US Federal Reserve (its central bank) hiked interest rates to the highest level in the history of the country.

Money and credit creation fell and produced a recession, the worst since the Great Depression. But it was necessary to get inflation under control.

After 1982, there were additional debt-financed speculative frenzies, bubbles, and subsequent downturns.

The dot-com bubble led to the 2000-01 recession. The recovery from this led to a lot of money and credit going into residential housing.

The bust from this led to the 2008 financial crisis.

Because fiat monetary systems give lots of latitude on how much money and credit can be created, each cycle increased absolute debt levels and also non-debt obligations (e.g., pensions, healthcare, and various insurance liabilities).

As a result of all these IOUs, all central banks in the main reserve currency parts of the world – the US, developed Europe, Japan – had to compress interest rates down to extremely low levels and “print” lots of money due to cover all the obligations.

And as is common, during these periods of greater money and credit creation, a lot of this money goes into financial assets and makes certain parts of the population a lot better off but doesn’t do much for those that don’t have assets.

This leads to wealth gaps and other types of disharmonies. This includes values gaps, where there’s disagreement over the best system(s) for running a society and how much inequality in a society is too much and will be tolerated.

This feeds into political gaps and the types of political leaders that are elected, which leads to more political fighting and more internal strife and populism.

Internal conflicts typically get very bad when there’s an economic downturn. There are usually shifts to the left politically during these times.

This leaves us to where we are today

During the post-war periods, many countries start becoming more competitive with the top powers economically, technologically, and militarily.

Once they become roughly comparable to the leading powers, there is a greater risk of conflict.

After WWII, Russia and its satellite states (the Soviet Union), along with China, Vietnam, and other countries, followed a communist approach to resource allocation.

Because incentives aren’t tied to production, none of the countries that followed this approach became competitive.

Still, the Soviet Union developed the atomic bomb independently and built up its nuclear weapons arsenal to a level on par with (or even slightly better) than the United States.

This led it to temporarily be a threatening power militarily. Over time, more countries followed by developing nuclear weapons, recognizing them as the ultimate equalizer and geopolitical bargaining chip.

Outside their use in ending World War II in Japan when only the United States had them, they were never used. In today’s world, the use of nuclear weapons would ensure that both sides would be mutually destroyed.

The Soviet Union’s inefficiency meant it could not afford to maintain its military and overall empire (including supporting domestic needs). This became clear in the 1980s.

President Ronald Reagan prioritized military spending to keep ahead of the Soviets. They could not keep up and their system collapsed in 1991.

Communism was done away with. The breakdown of its currency, credit markets, and overall economy was bad for most of the decade that would follow. 1998 produced another debt market collapse.

After that, Russia was built back up into what it is today. Russia still significantly lags in overall economic development (e.g., GDP, GDP per capita) compared to the US and developed Europe.

From the early-80s to the mid-90s, most communist countries abandoned the communist system in favor of free-market reforms and globalization.

Some countries still call their single-party system the “Communist Party” (e.g., China, Vietnam) even despite the actual economic system being far different.

China and Vietnam are largely market-based economies and the state plays a decisive role in directing economic development. It might be thought of as a type of top-down capitalism. Both have capital markets, are open to foreign direct investment, and allow private ownership on many levels.

There are only a select few countries where communism is still in place.

For example, Cuba is still heavily centrally planned and most industries (and enterprises within them) are controlled by the state. Most Cubans work for the government. Venezuela is similar. North Korea is the most economically repressed country today.

But by and large, globalization and free-market economies have been the overarching frameworks since the mid-1990s.

But the overall mix between “state” (i.e., public sector influence and control over the economy) and “capitalism” (free market control of the economy and capital markets) goes in cycles and is always evolving throughout time.

The rise of China

The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 led to Deng Xiaoping shifting the country’s policies to more capitalist elements.

These included:

- the private ownership of many businesses,

- the development of capital markets to more efficiently allocate resources

- incentivizing commercial and technological developments, and

- allowing entrepreneurs to thrive in China’s system

Still, all this was under the strict control of the Communist Party.

Increased globalism and China’s large pool of cheap labor led to China becoming the most dominant power in global trade (exceeding the US) and increasing its wealth significantly.

China has also become:

- the world’s largest holder of global reserves

- the largest lender and investor in the developed world (e.g., through programs such as the Belt and Road Initiative),

- a comparable technology power to the US (even leading in some categories)

- the second-most dominant military power and

- the main geopolitical rival to the US

At the same time, it is growing faster than the US and most other countries in the developed world.

With such advancements like data and information management, quantum computing, and AI, this is a period of great innovation with the US and China leading the pack in these technologies.

This is making the world richer and more skilled than ever. If people can work together, there is great capacity for productivity to grow exceptionally and for the fruits of this to be shared in a broad-based way.

All three of the rises and declines of the main empires over the past 500 years follow a template that tends to repeat itself over and over again throughout history for basically the same reasons, though each has its own unique path and circumstances.

The last 500 years and its lessons for today’s portfolios

Evolution is a constant

It goes for everything – countries, companies, economies, currencies, people, everything.

Evolution occurs because of logical cause and effect relationships in which existing conditions and determinants create changes, which establish a new set of conditions and determinants, which create the next set of changes, and so on.

And it’s also tough to see this evolution up close. It’s common to miss the big moments of evolution coming at us in life because we each experience only tiny bits of what’s happening.

We are commonly preoccupied with “the now” and smaller details instead of having a broader perspective of the big picture patterns and cycles, the important interconnected things driving them, where we are within the cycles and what’s likely to transpire.

So people typically are surprised with circumstances they’ve never encountered before, even though these things rarely just come out of the blue.

For example, the 1920s in the US and most of the developed world were a time of great prosperity. So people could have never imagined what the 1930s were like with the Great Depression and the world war that would follow.

Just like the world order is changing now in similar ways with similar kinds of disagreements between the US and China on various fronts (trade, economics, capital, technology, geopolitics, military armament), and it’s not in the favor of the United States.

Over time the evolution of all this will make it clear who has what power. So if those with less power know that they have less power, they should drop into the subordinate position so the power and position changes take place without fighting.

Economic, social, and political factors

The mix of economic, social, and political factors producing internal and external conflict today can be observed in the backdrop of financial markets.

The US and other reserve currency markets in relative decline are resorting to significant amounts of debt creation and money printing to fill in for various liability and income gaps. This has produced a reliance on negative real interest rates in the United States, developed Europe, and Japan.

This is good for some assets in nominal terms. But it creates problems because people want to get out of cash and debt (bonds) when it doesn’t yield anything and more of it is being created.

Then it’s a matter of what the alternatives are, which follow a few main different categories:

a) Commodities, hard assets, and other alternative currencies (foreign currencies, cryptocurrencies)

b) Different countries (i.e., a form of capital flight)

c) Different types of bonds (e.g., inflation-linked bonds instead of nominal, foreign bonds where there are higher returns rather than domestic fixed income)

d) Certain types of stocks

e) Private assets and going outside traditional liquid markets

f) Sources of returns uncorrelated to traditional betas/asset classes (e.g., liquid alternatives)

Negative real interest rates

The US and developed Europe have negative real interest rates based on their sovereign debt yields many years out minus their inflation rates. Japan is sometimes an exception because it has a problem getting inflation up to even zero, a level policymakers want to at least always hit to avoid deflation.

This is the kind of environment where cash and bonds are not attractive because there’s so much of it to contend with bloated debt and non-debt liabilities (e.g., related to pensions, healthcare, other unfunded obligations) and the incentives to hold these things is so low given where the yields are.

The entire purpose of trading and investing is to at least maintain purchasing power. This doesn’t occur when the instrument you’re holding yields less than the rate at which your spending power is declining.

That pushes more market participants into stocks and other alternative assets.

Commodities, hard assets, and precious metals

Holding all else equal, commodities, gold, and other types of alternative currencies become more attractive.

While things like gold, silver, and other precious metals don’t have an explicit yield to them (technically their yields are negative because of storage and insurance costs), there is more demand for them when traditional financial stores of wealth (cash, bonds) see their real returns decline.

Geographic diversification

Geographic diversification becomes more important. While real returns can become bad in lots of assets when they’re printing agressively, in other countries circumstances are different. It’s a matter of how policymakers are pulling their levers across countries.

Market participants naturally will be concerned about the implications of developed markets’ dependence on negative real interest rates to prop up their economies and capital markets.

There are three main impacts:

i) a low discount rate on earnings (meaning bonds, credit, and equities go to very high levels relative to the earnings they produce and become riskier)

ii) bonds provide little income and risk diversification when their yields are so low

iii) a weak currency (because fewer want to hold it when it doesn’t yield much and it’s being devalued by printing a lot of it)

While real yields are a mainstay of developed markets, in many developing economies (Southeast Asia in particular) they have a normal interest rate on cash and a positive-sloping yield curve.

To go along with what printing money does for a currency (devaluation), more capital will move out of “Western” economies and into “Eastern” economies.

This is not only China because there are a number of other countries in the East where the market environment is different from that seen in Western countries.

Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

More people will want to own inflation-linked bonds relative to nominal rate bonds.

Nominal bonds can’t go much below zero. Past a point doing so does little to incentivize additional activity among lenders and borrowers. Accordingly, there is no limit to how negative real yields can go.

Real yields are equal to nominal yields minus inflation. That means the “price cap” or “yield floor” on nominal bonds doesn’t apply to inflation-linked bonds the same way it does their nominal rate counterparts

So, the upward potential price trajectory of inflation-links bonds is not as constrained.

Stocks and companies that retain their real value

Companies that have stable cash flows are natural types of bond replacement candidates when bond yields become terrible.

For many investors, and institutions like pensions that are more conservative, having a fixed income alternative is a top focus.

They want to obtain moderate yields but don’t want to take on a lot of risk.

For example, someone might have a million dollars saved up for retirement and be at a point where they don’t want to take too much risk. They’d be perfectly happy getting about five percent annual returns on that to provide a full income.

That would provide an income of $50k per year. This would fund a reasonable lifestyle most places and would help avoid having to draw down the principal.

If they earn more than that, that’s great but it’s not the most important thing.

This means those with an income generation focus – commonly individual investors, pensions, endowments, foundation, and similar entities – are going to look for safer types of equities given they can no longer get this five percent yield, or at least a couple percent in real yield, out of fixed income markets in a safe way.

Certain stocks that involve selling products people need to physically live (e.g., consumer staples) can be good stores of value. They won’t be the most exciting investments, but as a whole they’ll be more reliable than the average stock.

These companies don’t rely on interest rate cuts to help offset a loss in income. Their products (e.g., food, the everyday basics) will always be in demand.

It may not necessarily be the same companies that do well and have sustained success over time. But a diversified mix of consumer staples is likely to do well in reliably growing their earnings.

These might include companies like, for example, Coca-Cola, Proctor & Gamble, PepsiCo, Costco, Wal-Mart, and others that sell food and everyday items.

They won’t produce the big ups and downs in prices like companies that are sensitive to interest rates or highly interconnected with how the economy performs, like a manufacturing business.

Traders and investors can feel pretty good about the notion that these companies, collectively, are very likely to see their earnings increase fairly reliably at about the rate of nominal growth.

Some might also consider utilities and real estate to be in the same category. They provide basic services (e.g., water, electricity, heating, shelter) and provide basic needs. Real estate is a mixed bag as more money is going into data centers and warehouses and less is going into malls and commercial real estate.

But these businesses tend to have a lot of debt, meaning interest rates matter to their valuations, which is something they don’t have much control over.

Companies with strategic importance

Companies that are strategically involved in the creation of defense systems, aerospace, telecommunications equipment, cyberdefense, and overall military capabilities are also likely to have increased importance.

Governments may not want to manage economies at the micro level by necessarily picking winners and losers (even China), but they will want to support top companies and top performers if required.

“Innovators”

Certain technology companies are in the “store of value” category as well.

Companies that are involved in the creation of technology that will help drive productivity gains going forward can serve the same type of role in a portfolio (growing earnings). They involve more risk.

Private assets

People will also increasingly turn to the private markets for greater yields.

Having a liquid portfolio has a big set of advantages. This includes being able to change your mind quickly and not being stuck with an asset if the reasons behind owning it have changed.

Owning a stock carries the advantage of being a passive investment. You own a part of a business without needing to dedicate your own time to it like those managing and employed by it.

But the lack of easy liquidity and, in many cases, the need to actively manage investments in the private markets will be worth it for some when the prospective returns sufficiently compensate for it.