Cross Currency Basis Swaps: Hedging FX in a Global Portfolio

In basic terms, the cross currency basis is a measure of the relative shortage of a certain currency in the market relative to its demand. Cross currency basis swaps reflect this relative shortage and work as a type of currency hedge, or a type of hedge on a broader global portfolio.

The premium or discount reflected in the cross currency basis theoretically shouldn’t persist long-term.

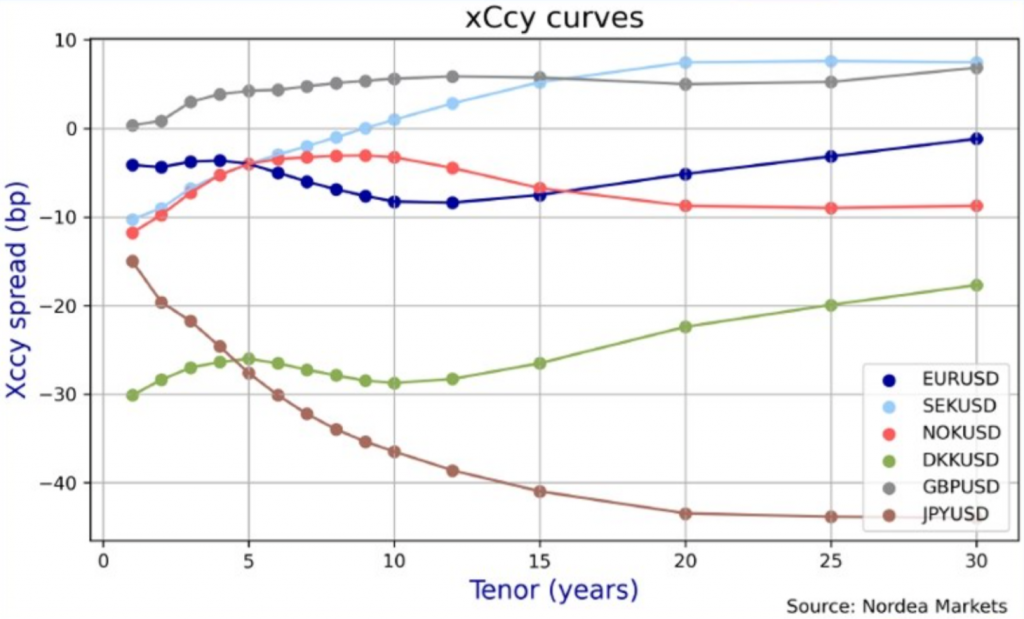

Examples of Cross Currency Basis Curves

In theoretical finance, covered interest rate parity states that the forward exchange rate of a currency pair should be the result of the spot rate plus the differential associated with the interest rates of each currency.

The interest rate parity formula is as follows:

F = S * (1 + domestic interest rate) / (1 + foreign interest rate)

Where:

- F = forward exchange rate

- S = spot exchange rate

For example, if the US dollar were to provide a two percent interest rate and the Japanese yen were to provide a zero percent interest rate, holding USD relative to JPY would provide a two percent carry.

That means that USD/JPY would expect to trade at a lower exchange rate in the future to find a new equilibrium given the higher payment of interest on USD. And the JPY relative to the USD would expect to trade at a higher exchange rate.

The market may anticipate inflection points in this relationship in the future, such as when one central bank eases or hikes interest rates relative to another, causing the slope of the curve to change.

For example, traders might expect the USD and JPY to have almost equal exchange rates, but expect the US to begin hiking interest rates relative to the USD.

This would steepen the JPY/USD futures curve at that point where rate differentials are expected to go higher.

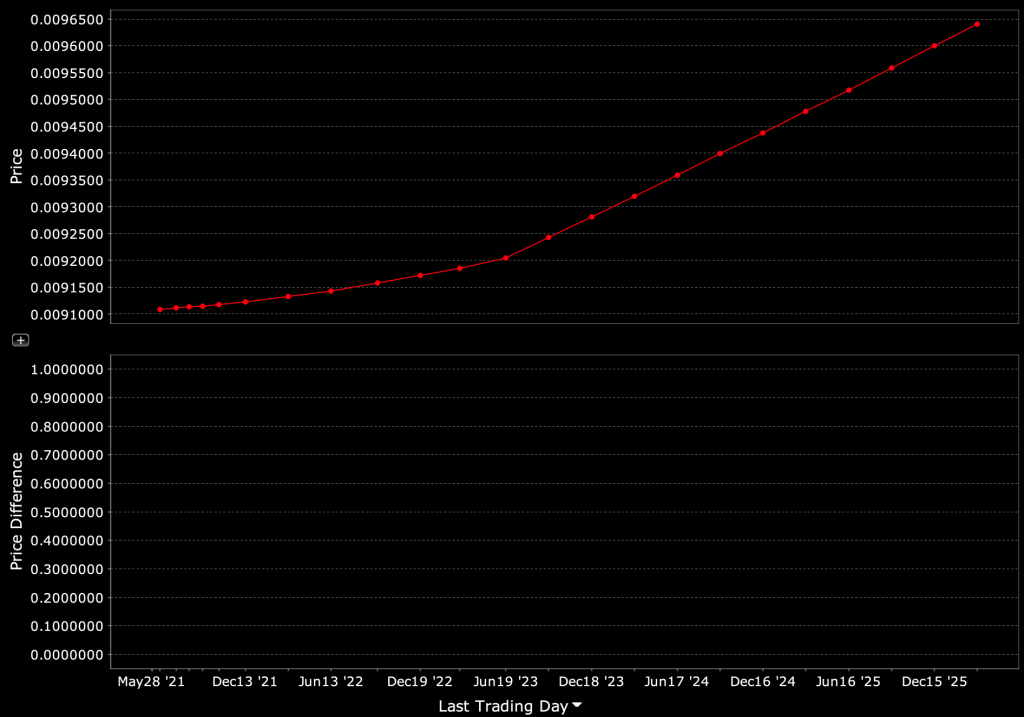

Example of a JPY Futures Curve (relative to USD)

(Source: Interactive Brokers)

Generally, you will see the EUR, JPY, and CHF futures curves are all in contango (upward-sloping futures curve) against the USD. This is because they typically have lower interest rates than the US and don’t have higher future interest rates priced into their curves like the USD often has built into its yield curve.

Negative cross currency basis meaning

The cross currency basis is typically quoted as a negative figure.

When the cross currency basis is negative, it reflects a relative shortage of a currency relative to another. The more negative the basis, the greater the shortage.

Cross currency basis is commonly measured relative to USD

The cross currency basis is commonly applied to US dollars, given it represents the bulk of what’s used for global reserves, debt, transactions, and invoicing.

Accordingly, the cross currency basis often refers to the level of dollar shortage in the market. The Federal Reserve creates dollars and this supply is matched relative to dollar funding needs globally to meet the needs of trade and capital flow funding.

Cross currency spreads are considered a risk-free opportunity

Any residual in the cross currency should be short-term. Typically it is arbitraged away by entities (human traders and machines) who are always observing these markets.

Short-term basis in the cross currency markets are a signal of liquidity and credit risk.

Long-term basis is a signal of hedging demand.

The more negative the basis, the more severe the shortage.

How to benefit from the cross currency basis

For dollar-funded market participants, a negative basis is beneficial when working to hedge currency exposures.

When hedging FX exposures, a negative cross currency basis is favorable. Hedging FX for a dollar-based trader or investor means lending out a dollar and receiving it back at some point in the future. This earns them the cross currency basis spread plus whatever they earn on the yield of their foreign investments.

The use of cross currency basis swaps is most common among macro traders and has also been employed by central banks.

The Reserve Bank of Australia used basis swaps of its foreign exchange reserves against the JPY in order to enhance its returns.

Even though Japanese short-term debt yielded negatively, once the basis was accounted for, the yield was higher than the short-term sovereign bonds provided by other reserve currency countries.

This is one reason why negative yielding debt can look attractive to a non-domestic entity – it may yield positively (or simply yield more) than other alternatives they can find for the same risk.

The overall implication is that even if bonds yield very low to negatively in domestic currency, they might provide higher yield when translated into a foreign currency.

Other uses of cross currency basis swaps

Corporations use cross currency basis swaps as well.

If a German company wanted to fund its US operations overseas, this invites currency risk since the company is EUR-funded.

To hedge its FX risk, the company could enter into a one-year EUR/USD FX swap with a bank (the usual counterparty).

The German company would swap an amount of domestic currency for USD at the prevailing spot rate, and agree to swap the funds back at the same rate one year from now.

The German company doesn’t actually own US dollars. So it will need to pay back the US interest rate that’s agreed upon (e.g., Libor, SOFR) and receive the agreed-upon European interest rate (e.g., Euribor, €STR) from its counterparty.

Based on interest rate parity theory, it should be this simple. But in reality, the supply and demand for certain currencies vary. As a result, the counterparty that’s lending in dollars will ask for a price premium when there’s higher demand for the USD.

This gets called the cross currency basis. Then the German company will not only pay the US rate and receive the European rate, but also pay the cross currency basis.

For non-USD traders and investors, the cross currency basis could increase the hedging cost of investing in dollar assets. They’ll not only borrow dollars today and pay it back in the future but also potentially have the additional hedging cost added to the interest rate differential between the two currencies.

As a result, the cross currency basis is an important component of currency management in a portfolio that involves itself in various global markets that may bring different currency exposures.

Generally, the Fed tends to be ahead of ECB, BOJ, and other central banks in its desire to tighten monetary policy by tapering its quantitative easing operations or by hiking interest rates.

So a dollar shortage is generally a risk in some form, which can cause the basis to go negative. As a result, traders and portfolio managers involved in holding FX and hedged FX exposures need to be mindful of the hedging cost associated with these positions.

The cross currency basis swap as a macro hedge and USD liquidity reversal bet

The cross currency basis swap is often considered the cleanest way to bet on a reversal of USD liquidity trends. (The OIS/OIS cross currency would be the purest way.)

When central banks create liquidity the basic uses of those funds are spending, savings, and purchases of financial assets.

A reversal in liquidity commonly means a reversal in financial asset prices if done at a rate faster than what’s discounted by the market or if the conditions of the economy change such that it makes a tapering of policy less favorable for markets.

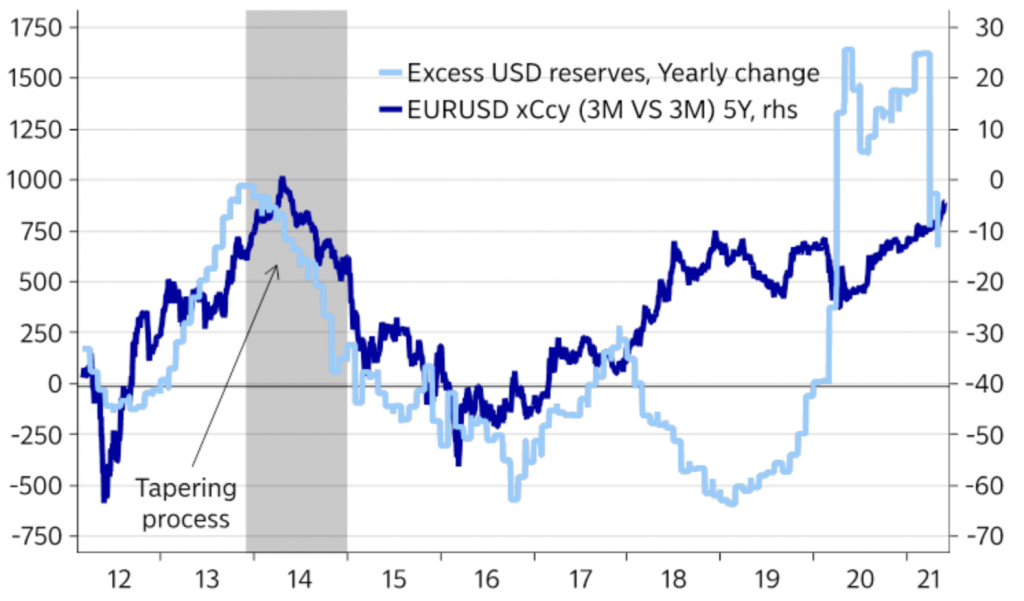

When the Fed began tapering in the well-known case of 2013, it led to a reversal in the trend of the cross currency basis as well (or essentially a repricing of USD liquidity since it was no longer abundant).

Excess USD Reserves vs. EUR/USD Cross Currency Basis

(Source: Macrobond, Nordea)

The USD is still fairly strong relative to its fundamentals. The US runs a trade deficit, deep fiscal deficit, and runs negative real interest rates on a majority to all of its yield curve.

The desire to hold currencies under those circumstances is generally low. And it’s especially difficult for a currency to maintain the same value under those conditions if one does not have a reserve currency.

The combination of a strong currency and cheap cross currency basis is generally rare. Therefore, it’s a good opportunity for those who want to hedge assets in that currency.

Moreover, the USD cross currency basis is not just an FX-only phenomenon but has a high correlation to the trend of global equity markets.

The USD cross currency basis is commonly around 75 percent correlation the MSCI World index on an annual basis.

Therefore, owning the cross currency basis is a quality hedge for a macro trader’s or institution’s portfolio, or company whose business prospects are correlated to the health of the global economy and/or asset markets.

Policymakers’ response to a negative cross currency basis

A central bank is likely to respond to a persistent and material negative cross currency basis by expanding liquidity. A negative basis signals liquidity and credit risk concerns by market participants.

And they’re generally already aware of these issues without looking at the cross currency basis of their own currency relative to others in the first place.

If they go too far in expanding liquidity or easy monetary policy is no longer necessary, they can begin tapering the level of permanent open market operations (POMO) or hike interest rates.

Conclusion

A cross currency basis swap involves the exchange of the principal and interest payments in one currency for the principal and interest payments in another currency.

It is an OTC derivative typically exchange between a bank and a company, hedge fund, or other entity that has foreign exchange risk exposure. They can be customized to meet the needs of the parties involved.

The cross currency basis is essentially the risk that the banks have when they fund US dollar assets with liabilities in non-USD currencies.

It is translated as a basis spread added mainly to a US Dollar benchmark rate commonly agreed to by banks such as USD LIBOR, SOFR, or another representative interest rate.

The existence of the cross currency basis could trigger arbitrage trades. However, banks and other institutions may face regulatory restrictions that prevent them from taking advantage of these profit opportunities.

Overall, receiving the cross currency basis is a common tactic for traders, companies, and other institutions with foreign currency exposure to use as part of an FX hedging program.