The Biggest Problem For Investors Going Forward

The biggest problem for investors is the reality that asset returns will be very low going forward. There will be lower-than-normal returns with greater-than-normal risks relative to the placid environment traders have recently experienced.

This is a problem given what the returns on assets will need to be to meet our future obligations. For example, many pension funds base their assumptions on the idea that they will obtain a long-run return of 7 percent per year.

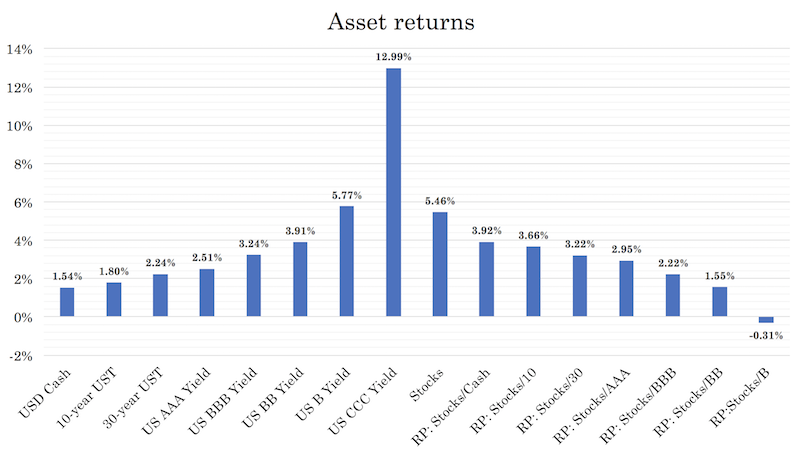

Below, we can find the returns between the most conservative investment (cash) through the highest risk gambit of all public asset classes (CCC or lower credit). To the right of the CCC or lower column in the graph shows the risk premiums (“RP”) between various asset classes.

No longer can investors enjoy the luxury of getting 10-11 percent annually on equities and 7 percent per year on safe government debt.

If a pension fund has 60 percent in equities (5.4 percent future return), 20 percent in bonds (2.5 percent), and 20 percent in alternatives (6 percent), this comes to a weighted-average return of just under 5 percent. This also comes with a 95 percent correlation to the stock market.

The bond component, because the volatility of equities is some 2x-3x that of bonds, provides little in actual diversification. While there might be 20 percent in bonds in notional dollar amounts, the actual risk composition is much less because of the lower volatility of fixed income. The overall risk will still be heavily skewed toward equities.

Because the expected reward-risk, or prospective returns relative to the levels of volatility, is so poor in regular asset classes, this makes cash at 1.5 percent reasonably attractive to hold to some extent.

For example, if you take the expected returns on cash (150bps) and the expected returns on bonds (180bps for the US 10-year and 250bps for USD corporate triple-A) and the expected future returns on stocks of 5.4-5.5 percent, that extra 3-4 percent for investing in equities over bonds or cash can be lost in a day or two due to their structurally higher volatility.

Moreover, when there is a sell-off in stocks, this has a negative pass-through into the rate of economic activity. So, there’s a self-reinforcing cycle given central banks manage economies so heavily through the conduit of the capital markets through their quantitative easing programs.

On top of that, the 150bps on cash means that the Fed has only another 1.5 percent before front-end interest rates are theoretically maxed out. Manipulating the short end of the yield curve is the primary way central banks achieve their monetary policy objectives. This is already maxed out in the European Union and Japan, the other two main reserve currency jurisdictions.

When that’s exhausted, they move on to quantitative easing to lower interest rates further along the curve – mostly government debt buying, though the ECB has purchased corporate debt and the BOJ has moved into exchange-traded funds.

Those spreads are tight in the USD curve (150-230bps) and already gone or close to being gone in Japan and various other European countries. So, those risk premiums are already absent.

Yet economic conditions are relatively good and benign. Accordingly, the question becomes what policymakers will do when there’s a downturn to stimulate the economy. And the downturn doesn’t have to be particularly large; it can simply be a mild reduction in aggregate economic activity before central bankers find themselves struggling to hold everything together.

There’s fiscal policy, but that’s a political process and many countries are already riding high deficits as a percentage of their output.

Even though G-7 FX volatility is very close to being the lowest it’s ever been, with interest rate policy nearly exhausted, we should expect currency volatility to become higher than normal.

When nominal interest rates can’t be lowered by central banks and relative interest rates between countries can’t be altered, that means currency movements must be larger to avoid economic volatility.

This, in turn, creates “currency wars”, the breakup of fixed exchange rate regimes, and overall greater currency risk for investors and traders of all stripes.

If all of the world’s largest economies face the issue of being out of traditional monetary tools, then exchange rates shifts will not be effective in helping stimulate growth. This is because exchange rates are all relative to each other. A change in an exchange rate will tend to benefit one country at the expense of another.

While the Federal Reserve will continue to ease policy through interest rate cuts and quantitative easing, it will be less effective than it was in the past. There’s only so much left in the tank and nominal growth is still around 4 percent (2 percent in real terms).

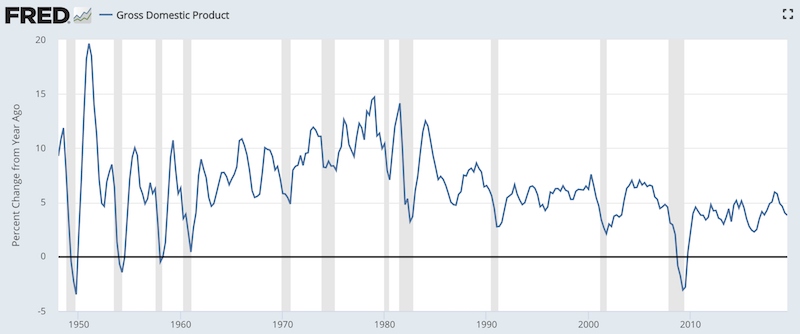

In the past, when inflation was structurally higher in the US, nominal growth (i.e., the sum of real growth and inflation) would normally remain above zero.

(Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis)

Because inflation is now so low (around 2 percent and often under), even a relatively mild recession of a 2 percent year-over-year contraction in real growth would see nominal growth drop below zero. During the financial crisis, nominal growth dropped to below negative-3 percent in year-over-year terms.

The future of monetary policy

With current policy forms out of room, future monetary policy objectives will likely need to be targeted at spenders instead of savers and investors through the manipulation of interest rates and asset purchases.

No longer are central bankers constrained by the thinking that the zero interest rate level is an effective lower bound. Now, many economists and policymakers believe that negative interest rates are viable as a stimulatory measure. Japan employs negative interest rates; the European Union uses them; and Switzerland is almost a full 100bps in negative territory in the front end of their curve.

Negative interest rates will make cash a little bit less attractive to push savers and investors into other assets, but not to a huge degree. It won’t incentivize savers and investors into assets that will help finance spending.

Quantitative easing will help drive asset prices higher. But people will still want to save and borrowers and lenders will still be cautious with each other.

Accordingly, a third form of monetary policy is likely to more directly put money in the hands of spenders and tie it to incentives that force them to spend it.

For example, each citizen could receive a “stipend” from the government at periodic intervals (it could be means-tested or simply sent to everyone equally) and force them to spend it by, e.g., having it disappear after some time. This is what’s commonly called “helicopter money”.

Another form could be fiscal and monetary policy coordination, which some countries already do (like Japan with Abenomics). This is what’s essentially known as debt monetization, where the central bank receives authority to participate in government spending and consumption programs.

In neither of these proposals are the rates or bond markets any longer a constraining force in pushing out monetary policy objectives.

Over time it’s likely that you’ll see more centralized underwriting of private sector credit, and more so-called “state capitalism”.

This means greater coordination between fiscal and monetary policy where the central bank isn’t merely transmitting its policy through the banking system and bond market but rather by directly assisting spending and consumption programs that are traditionally solely within the purview of fiscal policy. In other words, spending will become increasingly separated from borrowing.

Other forms of tertiary monetary policy and tweaks beyond helicopter money and debt monetization could take several different forms:

– capping the cost of capital (similar to what the Fed did from May 1942 to June 1947 in light of World War II and follow-on programs such as the Marshall Plan to assist international recovery efforts)

– for helicopter money, most countries would either need to change the laws to authorize it or circumvent it through a scheme where the central government could, for example, deposit non-redeemable, non-transferable, zero-coupon bonds with the central bank

– increasing commercial bank nationalization

– raising reserve liabilities and reserve ratios

– eliminating interest on excess reserves

– eliminating commercial banks’ ability to accept private sector deposits (commercial bank deposits are not put back to work; there is no matching investment or consumption outlet, unlike the way non-banks use deposits)

Conclusion

The biggest problem for investors moving forward involves the reality that asset prices have been bid up to high values, which has lowered their forward returns. The unavoidable reality is that the value of an asset, whatever its characteristics, cannot over the long term grow faster than its earnings do.

Earnings are a function of growth rates. The US economy and other developed market economies are no longer going to be growing at the rates they once did due to flat-lining and declining working populations, higher dependency ratios, slower productivity growth, and high debt levels.

Lower interest rates and central bank asset purchases simply pull forward future returns. They do not structurally increase them. Stocks might not be extremely overvalued relative to cash, but their absolute returns will be low going forward like all other asset classes.

Future monetary policy objectives are likely to be run not through the rate and bond markets (i.e., targeted at savers and investors). Rather, they will likely be targeted at spenders either through greater fiscal and monetary policy coordination or by putting cash directly in the hands of spenders and unfetter the entire process from borrowing as risk premiums compress further out along the curve.