Where are the ‘bond vigilantes’?

‘Bond vigilantes’ are supposedly the traders who regulate interest rates based on the notional intrinsic value of bonds.

Governments all over the world are stimulating economies in a big way and showering money all over the place to offset the drop in demand. In an bygone era with less government intervention in the bond market, you might expect this to be bearish for bonds.

If the government spends a lot of money and doesn’t have the revenue to cover it, that means having to fund the spending by issuing bonds.

More bond supply, holding demand constant, means interest rates go up. Bond prices and yields move inversely. If rates go up, prices go down. In other words, more bond issuance would be bearish for the price of bonds.

Initially, when there were talks of an unprecedented rescue package from the US government, bond yields went up due to markets discounting in a new large wave of Treasury bond supply coming onto the market. Namely, there’s a worry of who has the means to buy all that debt. It couldn’t possibly come from the private sector given the magnitude of the issuance.

This, at least for a day, created a period of selling in risk assets. Interest rates went up, reducing the prices of stocks and other risky assets through the present value effect.

When it became known that the Fed would indeed in fact be prepared to buy all of this new issuance (“unlimited QE”) – or even create the money and supply the Treasury directly to circumvent needing to issue bonds at all – bond prices went back up and yields dropped.

To support these government expenditures, central banks can’t allow interest rates to rise much. It would also lead to stronger currencies in relative terms. Stronger exchange rates disadvantage countries in terms of trade (i.e., exports become less competitive) and in their overall balance of payments situations. When you have a lot of debt, you generally want a weaker currency to ease the burden.

Bad news will support government bond prices (in countries with no material credit risk) and economies will remain underwater for potentially years relative to their high-water mark. This may be less true for a country like China, which was growing at a higher rate than developed markets and had more ability to stimulate its economy through monetary policy (i.e., higher interest rates), relative to developed markets. It is likely to recover lost output more quickly.

Bond yields can’t fall indefinitely

At the same time, there’s a limitation to how far bond yields can fall.

Some central banks have ventured into negative interest rate territory and kept them there despite a relatively calm economic period since the financial crisis. The US Federal Reserve has so far internally disqualified the idea of negative rates. But most of developed Europe is there via the ECB and Switzerland is at around minus-100bps. Bond rates are negative in most jurisdictions out at least 10 years.

But there’s a question of how effective it will be.

Cash becomes a little bit less attractive if interest rates go from being zero to negative. You’re now paying a penalty to hold it even in nominal terms.

But it doesn’t necessarily mean that a stock, a piece of real estate, or a distressed company that could use the funding is necessarily more attractive, particularly relative to its risk.

People still need safety and they still need sources of liquidity. Lenders will still need to be cautious about what type of lending they do. If economic prospects are bleak, which is what a zero or negative interest rate regime implies, then debtors need to be cautious about what type of borrowing they do as well.

For lending institutions and others that rely on the “borrow short to lend long” model, a flat or inverted yield curve is not in their interest, which can be a drag on credit creation. This is what led the Bank of Japan to institute yield curve control as part of its own monetary policy initiatives. Lending institutions rely, in vary degrees, on that spread. So, central banks can’t feel comfortable with a shape of the yield curve that isn’t at least somewhat steep.

Shorting bonds? Not so fast

I wouldn’t expect much out of bonds either way, long or short.

The Japan antecedent

When Japanese government bond yields became very low after the country’s 1989 crash – and later German government bonds (“bunds”) after the financial crisis – many macro traders hopped on the short bandwagon.

In each case, they reasoned bonds couldn’t go much lower given bond markets can only go so low. So, the risk/reward is theoretically asymmetrically skewed in a favorable with a short position, betting that yields would eventually need to rise.

Some believed that interest rates would eventually be normalized or that all the central bank stimulus would even lead to inflation. This was erroneous because of the debt burdens of developed market economies exerting a long-term secular deflationary force on the economy. When debt is high relative to income, the capacity to produce more credit growth (a key source of spending power that feeds into demand) becomes limited.

The lack of inflation would prevent interest rates from going up much, given inflation is a large feed-in to the yields of assets with no material credit risk.

This short JGBs (and short bunds) trade became known as the “widowmaker” trade – something that went poorly and could continue to go wrong.

Short JGBs has been a bad trade ever since Japan’s bubble popped over 30 years ago. Not only that, but when interest rates go down, the duration of financial assets lengthens, making them even more sensitive to movements in rates.

What about European periphery debt?

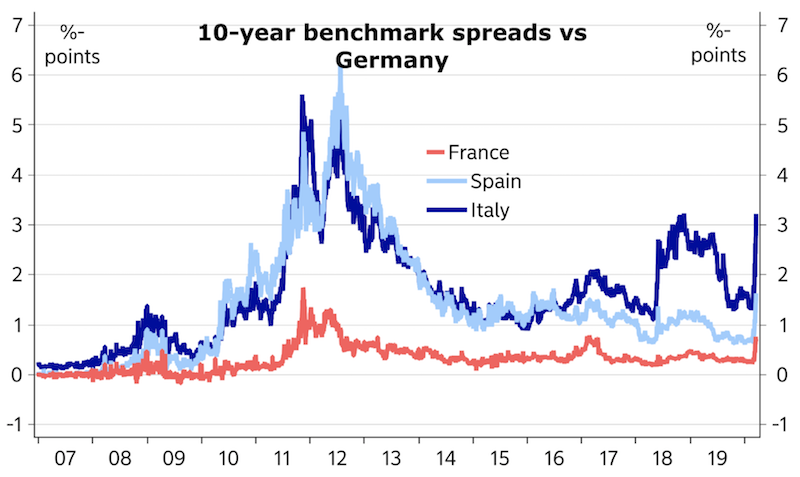

French, Spanish, and Italian yields increased relative to German yields when the markets began to discount in higher budget deficits.

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Many traders use a “long bunds, short [enter name of weaker euro credit]” approach to bet on increased credit risk in the euro zone.

The German bund is the euro zone’s top reserve asset, as the most creditworthy country in the world’s second-top reserve currency. Germany is also fiscally austere in relation to Europe as a whole and has a stronger overall economy, leaving it a euro that’s excessively weak for its own set of economic conditions. That keeps its budget healthy and issuance of bunds relatively low. Conditions in Germany are different from the remainder of Europe.

As a result, it’s hard to drive bunds higher when there’s a limited supply of them and high demand for them given their reserve asset status.

Nonetheless, in the euro zone, where there is no common fiscal policy and each country is pegged to the monetary policy of the region as a whole, this creates concern.

European debtor countries don’t have independent monetary policies and can’t create money to relieve their debt problems. (The UK is an exception, having its own currency and its own independent monetary policy.) Naturally, for the debtor EU countries tied together through the euro, this leads to problems between them and their creditors. Since the government can’t print money they have had to borrow a lot and tend to take on too much debt.

That means when there’s a downturn and they need to borrow more, they’re already tapped out and all sources of credit growth have largely shut down. As a consequence, they have low economic growth and chronic debt problems, creating social and political instability.

To an extent, countries can pay their debt if they impose taxes and cut spending or benefits. But austerity creates pain and economic hardship. There is only so much that citizens will take before they vote out governments trying to better balance out the spending and taxing equation – i.e., in favor of those that promise not to punitively cut spending and raise taxes.

Debtor and creditor countries linked by the same monetary policy with different economic conditions is a delicate issue. It becomes even more of one when there’s a downturn and the flaws of such a structure become more apparent.

It also means that debtor countries’ bonds are relatively unattractive for the creditor countries’ lenders. That leads to the wider credit spreads between stronger and weaker sovereigns.

If you are a debtor that can’t print money, like Greece or Italy, you are on a bad path depending on the severity of the issue. It leads to a period of restructuring that lasts a very long time and there’s a debtor-creditor tension.

In Greece’s situation in the 2011-12 period, if they had the capacity to print money (i.e., if they had been on the drachma and did not borrow significantly in foreign currency) they would have handled that by devaluing their currency.

But Greece was tied the euro, so that wasn’t an option. They lacked the capacity to pursue an independent monetary policy. Without the currency channel, national income had to come down instead. Based on the size of these deficits and the imbalance that had to be rectified, their GDP contracted 40-45 percent peak to trough.

The European debt crisis was a post-2008 phenomenon and is fresh in everyone’s memories. The drop in output related to the virus again creates a worry about the ability for debtor countries to pay their debts in full and on time. One person’s debts are another person’s assets. When one party can’t pay their debts, what the creditor thought was an asset, or a future source of income, either isn’t really an asset at all or one of reduced value.

Final Thoughts

We are very unlikely to see bond yields hold at any level like we saw during the 2017-19 period as domestic output languishes and debt burdens pile up.

It is hard to be either bullish or bearish on government bonds in each of the main three reserve currencies – USD, EUR, and JPY.

Safe used to mean safety in US Treasuries, particularly bills or the short-term cash dollars equivalent, as the currency most of the world’s debt is denominated in and the most used in global trade. Safety also meant, to a lesser extent, holding short-term debt in euro and yen.

Now, post-2008, because of the financial crisis, resultant QE programs used to fight the debt-related deflation that put $15 trillion of liquidity into the financial system, and recent large massive drop in output, all their sovereign borrowing rates are at zero or negative out many years on their curves.

Nothing provides any yield in nominal terms.

Where is safe and where is the least risk?

The US dollar is the world’s top reserve currency and still will be for a while, even if that means going off its reputation rather than its underlying financial health. The US outshines the other jurisdictions in its superior ability to securitize assets and its reliable legal and regulatory system. Europe remains dominated by bank financing. Most debt is denominated in US dollars, which means people want and need dollars in order to pay their debts.

But safety and low risk are not going to be in countries that have too much debt and other IOUs to pay in the form of healthcare, pension, and unfunded liabilities. All debtor countries are focused on printing money and this depreciates the value of that money. Creditor countries know this. They typically respond by increasing their gold reserves, as a type of alternative currency that is nobody’s liability.