Institutional Adoption of Bitcoin and Cryptocurrencies

In an environment where liquidity (money and credit) is abundant, it tends to bid up the prices of everything. Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies, which were once considered purely speculative fringe assets, are now increasingly seeing interest from institutional investors.

For most individuals, bitcoin and cryptocurrencies are a way to speculate. In a bull market, most people focus on the potential rewards rather than the risks.

In general, for most investment assets, it’s fairly straightforward to look at what your prospective returns are. The return on cash and bonds is advertised through what their yields are.

The yield on stocks is less known, considering they’re theoretically perpetual cash flow instruments and have a lot of volatility.

But by and large, the yields on stocks is typically above that of bonds. In the US, the extra risk premium of stocks over 10-year bonds is a bit over three percent per year.

The yield on stocks is considered the inverse of the price-earnings (P/E) ratio. If the forward P/E on the stock market is 25x, the reciprocal of that is the effective earnings yield, or about four percent.

When everything is going up, yield is more focused on because seems low. Risk premiums compress. (Namely, people expect less return for each unit of risk they take on.)

When volatility is low, it encouraged the uptake of financial asset purchases on leverage. When returns compress, it can exacerbate the behavior in order to get the desired returns on equity.

During more turbulent times, risk is the more important thing that people focus on. So, risk premiums expand.

Risks are trickier than returns to figure out

With traditional assets, most know what kind of returns they can expect but the risks are more difficult to assess.

Volatility is a known risk factor as it relates to one of the most basic elements of risk management.

But there are things that can happen outside the standard analysis – liquidity issues, a major fund liquidation causing idiosyncratic market movements, natural disasters – that are more difficult to prepare for.

With bitcoin and cryptocurrency, because it’s gone up a lot, the tendency is for most people to simply focus on what it can make rather than what it can lose.

In a different article, we explained that with bitcoin and any other cryptocurrency, you have to be prepared to lose 80 percent or more with it.

In developed markets, where most of the world’s traders and investors are, money can be borrowed at very low rates.

That brings on all sorts of risk-taking because practically everything that has a higher rate than cash is going to be purchased.

When the rate on cash is zero and the rate on bonds are at or close to zero, the only thing you’re left with as a discount rate is the risk premium. And the risk premium can be very low if markets are going higher and functioning in normal ways.

The paradigm shift we’re in

The most important thing to understand in the current environment is the zero interest rate lower bound, as it’s very pertinent to the bitcoin and cryptocurrency story.

Interest rates (in nominal terms) go only go to about zero or a bit below. After that, it’s hard to go any lower when central banks are going to target an inflation rate of at least zero.

This has multiple implications.

i) The tailwind of interest rates on supporting the prices of financial assets is mostly exhausted.

ii) An economic downturn usually entails an average interest rate cut of about 500bps. With rates at zero, you no longer have the ability to lower interest rates to push credit into the system and help create a recovery.

It’s more dependent on fiscal policy. There’s the political implications of that (i.e., dysfunction, willingness to do something).

And not only the willingness, but when you have negative, zero, or near-zero interest rates on your money and bonds, and they yield negatively in real terms, you no longer have sound money. So in many cases, there are material constraints and politicians can’t do anything.

This is particularly true in emerging markets where they don’t have reserve currencies and money printing creates balance of payments issues and directly feeds into inflation.

iii) The zero/near-zero percent bond yield means fixed income provides not only no nominal return, but negative real return. Bonds are a promise to deliver money over time.

With the negative real yields spreading from cash to bonds, buying a bond largely locks in the negative real returns and essentially represents a form of wealth destruction.

iv) Negative real bond yields reduce the value of bonds as not only a source of incomes but also as a means of diversification. If nominal rate bonds can’t go much below zero, they have limited price upside. We’ve seen the negative stock-bond correlation become far less reliable as expected in recent times.

This means traders and investors want alternatives. They’re going to go into other assets like:

- Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

- Gold and other forms of precious metals (e.g., silver, palladium)

- Commodities (industrial, agriculture, soft)

- Other countries with more normal investment environments

- Stocks that can be a type of fixed income replacement (e.g., consumer staples)

- Private businesses

- Collectibles

- Riskier ventures where there’s prospective return – e.g., startups, venture capital

- Alternative asset classes like cryptocurrencies and DeFi instruments

Asset class starvation

When yields are zero on cash and bonds, it means people will look elsewhere for yield.

Cryptocurrencies are largely a manifestation of all the liquidity that’s been produced.

Individual traders are largely looking to make a lot of money quickly or believe that it’s one way to potentially make multiples of what they put in.

Institutions are more deliberate and either looking for:

a) a currency hedge and/or

b) a reserve asset

This is why large institutional investors and central banks use gold. It’s the third-most common reserve asset behind dollars and euros.

It’s a type of asset that’s nobody’s liability, has a track record going back thousands of years, and is a type of contra-currency. Given gold has limited industrial use, its value is largely reflective of the value of the money used to buy it.

Gold going up or down has little to do with traditional demand like it does in most other commodity markets like oil or copper (consumption of the resource). Rather, it can act as a barometer for the value of money. Gold going up is simply the value of money going down in gold terms and gold going up in money terms.

It’s essentially something that can function as the inverse of money in a limited way. Generally, 5-10 percent of a portfolio’s allocation in gold is a level that can be both return-enhancing and risk-reducing.

There is no one answer about what stores of value one should hold in a portfolio. There are lots of unknowns and many viable assets that can function as a store of wealth. It has to be a diversified answer to avoid the big risks and inevitable drawdowns that a concentrated portfolio inevitably brings.

Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies’ institutional adoption

For bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies to receive consideration and adoption among the big players, it’ll need to exhibit a more gold-like character to it.

It’ll need to be:

i) more liquid

ii) the regulatory picture will need to be clearer, and

iii) it’ll need to be less volatile (regulation and diversification of its investor base would help)

Analogous periods in history

Many view bitcoin as a potential source of protection against inflation.

Inflation is not an easy question to answer because inflation can refer to price changes in anything, anywhere.

The post-2008 periods of the 2010s and into the 2020s saw lots of financial asset inflation because that’s where the money went.

When you lower interest rates and buy bonds and other financial assets as part of government monetary policy, it goes into asset prices by lowering the discount rate at which the present value of future cash flows is calculated (e.g., stocks and other longer duration securities) and by buying risk-free assets outright.

That’s largely run its course. In some ways, the period is analogous to the late 1960s heading into the 1970s.

i) Low inflation since World War II (CPI increased 1.3 percent as a year-on-year average from 1953 to 1965). Policymakers largely thought the risk of inflation was low simply because they had failed to recently generate it.

ii) The Fed had kept short-term real interest rates below the potential real GDP growth rate over a long period.

iii) Fiscal stimulus was high. President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs greatly expanded the US safety net, overall transfer payments, and the general role of government. There was also the Vietnam War spending.

iv) Fiscal spending continued even as unemployment had fallen to low levels. Easy monetary policy had continued despite the economy getting toward full employment. Inflation hadn’t manifested so the figured they’d continue to push the limits, as inflation is the main constraint on these policies.

v) In 1966, inflation climbed to the highest level since 1951. Inflation expectations help set real inflation because people plan ahead in terms of setting prices for goods, services, and labor (wages and salaries). “Inflation psychology” is a real thing – expectations can help set reality.

vi) The Fed eventually needed to tighten policy to curtail the excessive price pressure. Fiscal policy also needed to tighten.

vii) To pay for all the extra deficit spending, President Johnson signed the largest tax bill ever in the US in June of 1968. This is also a common theme today. The deficit is widening and the balance of payments issue is also something that will eventually need to be addressed. That means more of a concern of who will pay for all the proposals.

It’s not going to come in the form of tax funding, so more of the brunt will fall on the issuance of bonds and the dearth of buyers will likely mean more currency depreciation.

viii) In the late 1960s and early 1970s there was more civil unrest. Campus riots and shootings at Jackson State and Kent State occurred in 1970.

Externally, there was a Cold War with the Soviet Union, though today’s increased conflict with China has a different tenor to it.

The Soviet Union was characterized by high levels of inefficiency in the way they distributed resources. There weren’t traditional capital markets, so there weren’t the standard price signals on how to effectively allocate resources to meet the needs and wants of the people.

While China also calls its internal policymakers the “Communist Party”, it’s not like the old system that characterized the 1949 to early 1990s period.

China largely has a market-based economy, but with increased state support to sectors it deems strategically important to the long-term goals of the country. This includes things like technology, cybersecurity, aerospace, military, and other important functions.

The country that’s technologically superior tends to be superior in most other ways – economically, militarily, geopolitically.

ix) The Nifty Fifty was hot in the late 60s and into the early 70s. These were a number of glamorous stocks at the time, including those in the tech space. Household equity shares were climbing to all-time highs as valuations went extremely high.

Great earnings outcomes were extrapolated far into the future. And it was widely believed that low bond yields would be a fixture, which would help keep stock prices high because there were limited alternatives for investment capital.

Bubbles in asset prices festered and eventually had to be rectified.

x) Policies tightened and a mild recession was produced in 1969-70. The S&P 500 fell into a sizable bear market from late 1968 before bottoming in 1970s.

The 30 most popular stocks declined by an average in excess of 80 percent.

The inflationary 1970s

The easiness of the late 1960s and early 1970s gave way to inflation.

By the late 1970s, President Jimmy Carter was facing a difficult re-election bid and appointed Paul Volcker to Fed Chair. He promptly raised nominal interest rates into the high teens to break inflation and raise real rates to very high levels.

This caused a recession and a market downturn that lasted until August 1982, but it worked in dispelling the excess price pressures.

This also shifted the focus from a high level of government involvement in the economy that had characterized the 1960s to a new paradigm where the economy was largely led by the private sector.

When interest rates are very high, as they became in the 1980s, this meant standard monetary policy that makes adjustments in short-term rates is largely how the government will manage the economy. That changes the economics of borrowing and lending and those rates flow through the economy in their own ways.

Even since then, each cyclical peak and trough in interest rates during each hiking cycle (business cycle) has been shallower than the previous one.

Short-term interest rates, US

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

This is a function of the economy becoming more indebted relative to income. Raising interest rates increase debt servicing commitments more than they did previously simply because there’s more of it. So the “brakes” (i.e., hiking interest rates) work better.

What impacts borrowers isn’t necessarily the total load of debt, but the amounts that are due and when. If there’s a lot of debt, but the interest payments on it are low and it’s spread out, it’s less of a problem relative to when the interest is high and the installments coming due are concentrated.

If interest rates are down you can afford a higher total stock of debt. And this continues until interest rates hit zero. That’s when capacity constraints are reached.

Trading-wise, this means cash and bonds cease to be good investments (like in 1933 and 1971) and alternative stores of value become more en vogue.

Nominal and real interest rates were relatively high during the post-1981 period but declined because of this dynamic.

But because the return on financial assets was high from 1981 until 2008 (the debt crash), it was a good period for the dollar and bad for alternative stores of value like gold, which declines from 1981 to 2000.

Gold ($/ounce, in USD), 1970-2001

(Source: Trading View)

The converse is true about returns of financial assets today because we’re now pressing on the lower bound.

It’s bad for cash and bonds and good for gold, good for commodities, and good for new stores of value, of which cryptocurrency could conceivably be a part of.

The post-1981 period was also a good period for both stocks and bonds as there was a large favorable interest rate tailwind. Productivity rates were also materially higher and there was a population tailwind with the Baby Boomers entering their prime work years.

Fast forward to 2008

By 2008, the debt overhang became so bad that interest rates had to be lowered all the way to zero. That didn’t create enough of a lift because of the debt numbers relative to income, so the central bank had to move into money printing to fill in the gap.

That money went to buy financial assets – US Treasury bonds and some mortgage-backed securities. Europe followed later on.

That benefited those who held financial assets because that’s what it benefited. But it led to a fairly dissatisfying recovery for a lot of others who didn’t own them.

That drove greater wealth gaps. In combination with other forces, such as offshoring, some areas of the country saw economic opportunity lapse relative to places like the cities where there was more service work.

The economy grew, but there was more resentment that created more social conflict, more urban/rural splits, more populism, and bled more into what kind of political candidates became popular.

There became populism of the left (e.g., Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, AOC) and populism of the right (e.g., Donald Trump), and this flowed into other countries as well, including the UK, Italy, Netherlands, France, among others.

Some countries got more populist leaders (e.g., US) while others narrowly avoided them (e.g., France). The election of Biden over Trump in 2020 might suggest a preference for more traditional leadership – but it’s just one data point every four years.

And because of the Electoral College in the United States, elections tend to be narrowly decided by truly undecided voters in swing states, which are less than one percent of the actual voter base (about 500k people).

The US started to tighten monetary policy in 2015-16 in a cautious way. By 2018, they had raised short-term interest rates to just above two percent and realized that they couldn’t do so any further.

The market reacted very badly and by December 2018 the Federal Reserve gave up on tightening. If they caused a downturn by over-tightening they didn’t have enough room underneath their yield curves to pull out of it, so they decided that they essentially couldn’t.

All that pricing of higher interest rates and bond yields washed out of the market and 2019 was a great year for most financial assets as a rebound from 2018.

By 2020, there was a special event in the form of a public health crisis that caused a big drop in income.

Today

This accelerated trends toward the lowering of interest rates to zero and more asset buying. Because short-term and long-term interest rates hit zero or thereabouts, this led necessarily to more fiscal intervention in the management of the economy and that’s where we are today.

It’s brought up stocks, commodities, gold, and new alternative stores of value.

This is why you’re getting the move toward alternative asset classes. Bitcoin and cryptocurrency have done well. You’re seeing this move because of the expansion and devaluation of fiat money.

Central banks’ role

The world’s two top central banks (the Fed and ECB) have pushed back on the idea of raising rates despite the big recoveries in financial assets.

This is because their main worry is not inflation but deflation. When you have a big debt overhang, inflation is not the primary worry because of the way it works when there are large debt servicing commitments, the debt is denominated in your own currency, and income and productivity are not growing at a particularly fast rate.

If you do raise rates, you know it’s going to be effective.

If a top policymaker even hints at the idea of rates needing to go up earlier and/or faster than expected, equity markets tend to fall because that has a lot to do with what they’re underpinned by.

And then you have a wealth and social gap that don’t make the averages that representative of much. Policymakers have to be more mindful of this because of the threat to internal order large disparities can cause.

Revolutions start because of wide disparities (or perceived disparities and/or unfairness) and when enough people feel the system doesn’t work fairly for them.

Many haven’t benefited from the increases in financial wealth or increases in technological improvements. Labor has largely lagged relative to capital. Previous policies have largely benefited only a slice of the population rather than being broad-based simply because a small fraction of the population owns a big chunk of financial assets.

Monetary policy is not a good avenue to address this, and can be handled in a more directed way on the fiscal side, if they choose to.

And when you get monetary policy and fiscal policy moving in the same direction, you can start getting inflation. This is especially true when they are targeted and coordinated together. They largely haven’t been in a long time.

Even after the 2008 crisis, monetary policy was loose but fiscal policy was relatively tight.

Are bitcoin and cryptocurrencies related to inflation, actions of the Fed/other central banks, or are there changing social norms at work?

China is the leader in government-led digital currencies with the release of the digital yuan. This is arguably to some extent helping adoption of the private projects (cryptocurrencies) among larger players.

Digital government currencies can be used to help target policy (i.e., give money to specific individuals) and help bring it along as a reserve asset since it might be more convenient to use than currencies that are not yet digitized.

With cryptocurrencies and gold, one of the main goals is to protect wealth in a way that’s outside the reach of the government.

Crypto is not perfect because of its volatility. To account for this, people made the concept of the stablecoin. Stablecoins exist outside the government, but are backed (or should be backed) by another type of reserve asset. This is usually US dollars, though it can technically be anything that’s relatively hard in nature.

Gold also has volatility being a smaller, less liquid market that traditional sovereign bond markets. But it has a better historical track record.

But governments around the world don’t have enough money to service their debts. It’s not only a US problem, but a global one. It’s also not only national debt or headline debt figures, but massive amounts of other liabilities related to pensions, healthcare, and other unfunded liabilities.

Adding everything up, it’s more than 1,500 percent of GDP. By and large, many people don’t feel comfortable putting their money in government debt when a lot of it needs to be printed and the returns are so bad.

It’s impossible to grow your way out of that debt pile, so it’s all about the printing of money. People will want something that’s a type of contra-currency to be defensive because of the sheer volume of printing that needs to be done.

So, there are largely two themes:

i) Digitization, which is happening anyway with many different things, and

ii) The large-scale printing of money and types of potential non-government, non-debt assets that can be an offset to help protect against that

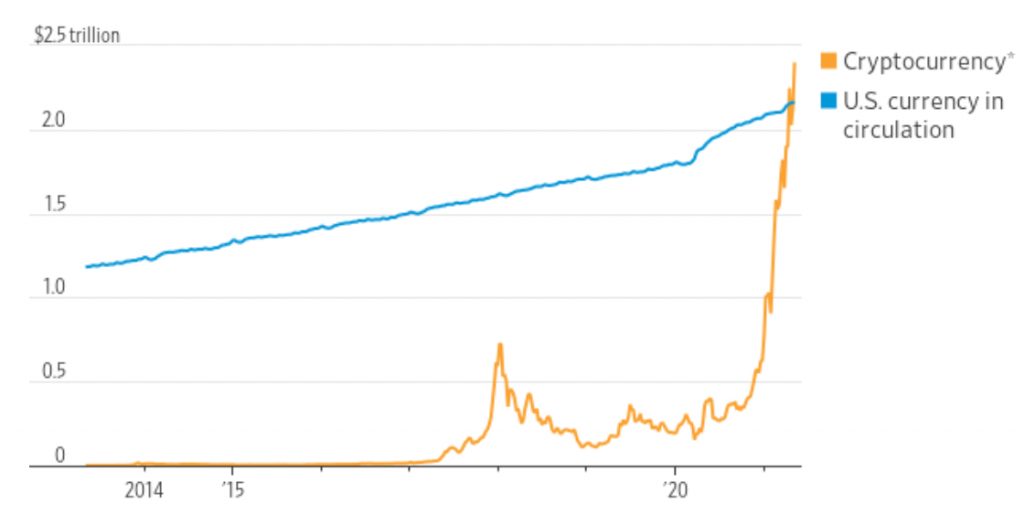

As of May 2021, cryptocurrencies were worth $2.4 trillion, according to CoinDesk, an information service. That’s more than all US dollars in circulation.

Cryptocurrencies represent more than all US dollars in circulation as of May 2021

Gold and precious metals are still largely preferred among older traders and investors while cryptocurrencies have more popularity among those who are younger.

How cryptocurrencies get on the radar of institutional investors

Most are still not convinced about bitcoin and cryptocurrencies for various reasons already mentioned – e.g., volatility, lack of regulation, lack of track record.

If bitcoin becomes very successful, will governments want it to exist?

If governments print money and it goes into non-credit related assets like bitcoin, gold, and other money and credit assets that it doesn’t control, it largely defeats the purpose.

Gold is something that’s known as a store of value and has been banned by governments throughout history for this history.

Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies don’t have the trust of institutional investors in the same way. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies might have some of the characteristics – e.g., limited supply – but it has much further to go.

Are central banks going to hold bitcoin as a reserve asset? It’s very far off from that.

Are corporate CFOs being reasonable for converting part of their balance sheet to bitcoin?

There is a lot of cognizance of the big-picture issues surrounding the potential for inflation and debasement of fiat currencies.

Corporate CFOs adding bitcoin as part of their “cash and cash equivalents” is one test for the viability of bitcoin.

To protect yourself in a world full of unknowns, having a diversified portfolio of various stores of value can be helpful. Even for businesses that have nothing to with cryptocurrencies or DeFi, or gold, precious metals, real estate, and so on, it can be helpful to own them as part of a diversification strategy.

Because of the recognition of the fact of where cash and bonds are – huge sums of assets that destroy wealth given the negative real yields – this is forcing allocators to think of where to go in terms of viable stores of value.

Is there anything analogous to bitcoin’s institutionalization historically?

There’s not a perfect analogous example to the big emergence of a new asset class.

Inflation-linked bonds (aka inflation-indexed bonds) are one example of an asset class that’s not necessarily new but has received more attention from institutional allocators over the past few decades.

The US came out with its own inflation-linked bond known as TIPS in 1997. The UK government came out with inflation-linked gilts (ILGs) in 1981.

With TIPS, they give you the CPI plus some type of yield in relation to the nominal rate bond (which can be a positive or negative addition or subtraction from the CPI).

No measure of inflation is perfect, but getting the CPI plus or minus something is one way to seek protection.

Inflation-linked bonds don’t get anywhere near the type of familiarity as something like bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. The latter is more “exciting” with the digitization, technology, and also the volatility and price appreciation.

While inflation-linked bonds simply spit out of a small amount of yield each year, bitcoin’s volatility can sell the dream of making a lot of money quickly.

Avoiding concentration

Many things are likely and all assets compete with each other for money and credit flows.

It might be tempting to put enough money into something to increase the odds of making a lot, but the converse is also true, especially with something that’s so volatile.

And when something has such a large impact on a portfolio through its volatility, it takes up more of the risk. If this isn’t compensated through higher return – that can be reliably obtained – the equilibrium amount held in a portfolio comes down.

There is no one answer as to what asset to own. Capital is always moving around and balancing well is going to improve a portfolio’s reward to risk better than practically any other tactic.

Many things can viably protect purchasing power, and at the end of the day, that’s essentially the only purpose when it comes to trading and investing – convert today’s money into more purchasing power down the line.

In today’s environment, with money printing, higher taxation, more social and political conflicts, if you recognize it’s a situation with a different playbook than just traditional stock and bond investing – the paradigm that’s worked since the early 1980s – you can see why things like alternative stores of value are so popular.

While it’s nice to grow wealth, as many get closer toward retirement and have larger sums of assets that they want to be increasingly protective over, many want to simply preserve how much they can buy with what they have.

This can means a combination of a little bit of cash, nominal rate bonds, inflation-linked bonds, stocks, gold, precious metals, industrial commodities, soft commodities, real estate, tangible assets, collectibles, and a small slice of cryptocurrency could make sense.

With crypto, you don’t need a lot for it to have an impact on a portfolio.

If you can combine and blend these assets well in a portfolio, you give yourself a chance of surviving through such a period well rather than having lots of volatility and big ups and downs in a portfolio that can throw you off your strategy or out of the game altogether.

Portfolios are still largely concentrated in stocks and bonds because that’s what people traditionally know and are told to do. And those have done well in the past, so that performance gets extrapolated forward even when the underlying conditions change to make that performance level highly unlikely to be sustained.

Questions institutional managers will need to answers as it pertains to cryptocurrency and DeFi

Cryptocurrency and DeFi (decentralized finance) are gaining some steam.

Some call it the “everything bubble” because of how much new money and credit has entered the system and how it bids up the price of everything.

Because of the liquidity, diversification has never been more important than ever just because the return has been whittled away.

As mentioned, there’s nothing you can point to that you really want to “gorge on”.

Because people know that the public sector is more involved in the markets and people are spilling out into alternatives like bitcoin and seeing that go, they have questions about whether that’s where they should be.

The adoption of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies outside of retail circles is happening first in some companies. Some do it just to diversify their cash reserves.

Others do it for that reason plus it can help with PR more importantly. It’s unusual so it captures headlines, which can help in their core business.

In the investment management or trading business, it’s first being adopted among smaller managers.

They don’t have committees or boards they have to get decisions through. So they’re much more flexible when it comes to adoption.

Larger managers also face the liquidity constraints that hold back adoption even if they wanted to. They can’t do it in material size. Bitcoin is still a small market and it’s by far the biggest cryptocurrency market.

They would need to see how that asset plays out over time before they can make allocation decisions about it. Obviously, more conservative investment vehicles like pension funds won’t touch it.

In some parts of the DeFi world, you can find interest accounts that are north of 5 percent and into the double digits.

So a smaller allocator might find that interesting in a yield-starved world.

But an institutional allocator will need to find something that’s tried and true like gold, industrial commodities, various forms of land (timber, farmland, other forms of real estate), and collectibles.

Collectibles is an entirely different category. That can include things like art, which is more traditional, or something like classic cars. It can also get more off-the-wall and toward things like rare whiskey, dinosaur fossils, trading cards, or something newer like NFTs or other forms of digitized assets.

Whatever it is, it needs to be reliable and be able to be done at scale for an institutional manager.

Conclusion

Ultimately, whatever becomes of this environment will depend on the quality of the decision-making.

When short-term and long-term interest rates are zero, more of the decision-making burden falls on fiscal policymakers (i.e., politicians).

That creates more room for good and bad. Will the money be spent wisely such that the productivity benefits pay for the costs?

Things like infrastructure can help boost productivity rates, though they have long lead times. The same can be said of education.

But governments don’t have a particularly good track record of spending efficiently. So there’s also the greater potential to waste a lot of money. It’s highly probable that there will be.

When governments are printing these magnitudes of money and engaging in this level of deficit spending, market participants need to be mindful of the effects on the value of money.

That means they need to be careful about how much cash and nominal rate bonds they own. Having liquidity in this form can be good to a point, but too much can be overly destructive.

Cash and short-term bonds seem safe, but over the long-run they’re the riskiest because of their low real yields, which are often negative and therefore wealth destructive.

All business owners need to think about what the environment means for them. This is true whether they invest in liquid markets or in a different type of business that involves the management of assets in some form.

Whether an investor, trader, or another type of business owner, what does this environment we’re in mean for the entity you own?