Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency vs. Bonds

Can bitcoin and cryptocurrency replace bonds?

Bitcoin and cryptocurrency have seen large price appreciation and considerations as an alternative store of value. On the other side of the spectrum, bonds are seeing price decreases with very low fixed yields associated with them.

Bonds – especially nominal rate bonds – have a lot going against them.

Their yield is fixed. And it’s at a very low level that can’t go much below zero. We know this because central bankers are always going to try to get a positive inflation rate.

If the inflation rate is at least zero, and bonds yield less than that, real rates are negative. So if you buy them for investment purposes, your purchasing power is eroding. And the entire purpose of trading or investing is to at least maintain – and preferably grow – your purchasing power over time.

Given this is the case, inflation has eroded all of the yield and then some in many sovereign bonds and many corporate bonds in the developed world.

That favors alternatives such as:

- Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs)

- Gold and other forms of precious metals (e.g., silver, palladium)

- Commodities (industrial, agricultural/soft)

- Other countries with more normal cash and nominal bond rates

- Stocks that can act as a type of bond replacement (e.g., consumer staples)

- Private businesses and/or one’s own skill set

- Collectibles

- Riskier ventures where there’s higher prospective return (startups, angel investing, venture capital)

- Alternative asset classes like cryptocurrencies and DeFi instruments

Then you have the other issues associated with bonds – the government’s printing a lot of money. Bonds are a promise to deliver money over time. When the government prints money at a faster rate than the real growth outcomes, then it’s being depreciated.

So, that means bonds are unattractive to a domestic investor – mostly concerned about the real return – and unattractive to an international investor who is mostly concerned about the currency.

The fiscal stimulus package associated with the 2008 recovery was $750-$800 billion, which was a massive amount at the time (about 5 percent of GDP).

$1-3 trillion in terms of the numbers nowadays are enormous spending packages considering US GDP is only somewhat north of $20 trillion. Two trillion in spending is just under 10 percent of GDP.

The government has big plans and big projects. It’s a gamble on whether these programs will pay for themselves. Governments don’t have a great track record of positive ROI spending. But it’s also a gamble not doing them since the US needs improvements in aspects like infrastructure to improve efficiency and help boost long-run productivity.

Financing the deficits

Budget deficits need to be financed. And those budgets are fairly easy for the United States and other creditworthy governments to finance because they can create the money to make up for any funding shortfall. So it’ll be paid in nominal terms.

So they sell bonds.

And they’re selling a lot of them, akin to World War II deficits of some 20 percent or more of GDP. That should normalize as the private sector can take over more of the economy. But the deficits will be structurally higher, especially as other liabilities come increasingly due (pensions, healthcare, other).

They can try to raise taxes. But that changes capital flows and incentives. The more you penalize capital the more you’re getting into effects on growth, so you can cause more harm than good past a point.

Then the question is – who are the buyers for these bonds?

There are some entities that have to buy the bonds to satisfy regulatory capital requirements (e.g., commercial banks). And there are some actors who have their own needs and motivations who are also interested in long-term holds.

But the total amount of demand relative to the issuance is not there in terms of free-market buyers.

They yield negatively in real terms and the policy mix is giving a structurally higher inflation rate. So domestic buyers largely don’t want a lot of them.

Increasingly, these entities are going to want to go to alternatives that are non-debt and non-dollar (and non-euro, non-yen, etc., where all these intractable issues exist). This could mean gold, hard assets, bitcoin, other digital assets, and so on. More unusual, bubbly parts of the market like SPACs and NFTs feed into this.

And international buyers are concerned about what the bloated deficits and printing of money mean for the value of the dollar.

So there’s a hole that needs to be filled.

That means more money printing as the Federal Reserve is going to have to buy the country’s debt. Otherwise it risks much of the debt not being purchased, which means lower prices for it and higher yields to establish a new equilibrium.

But higher yields flow through the economy. There’s the impact on lending and credit creation. There’s also the financial market considerations that are important for policymakers to take into account.

Assets like stocks are priced as the present value of future cash flows. The government bond rate flows through into the valuations of other assets. And their valuations impact incomes, wealth, creditworthiness, and so on.

So the main concern you have to have about owning nominal rate bonds is that if you left the bonds to the free market, there wouldn’t be the demand. Yields would need to rise to clear the market.

Central banks have to keep interest rates mispriced to keep the positive spread between nominal interest rates and nominal growth rates to keep the debt servicing in line and keep all the aforementioned factors – incomes, wealth, and creditworthiness – at sufficient levels.

And holding those bonds yields down is inflationary, holding all else equal.

If it’s not inflationary in goods and services, it will be in terms of asset prices just because that’s the primary channel it runs through – i.e., governments buying financial assets and reducing yields, which increases asset values through the present value effect.

But at the same time, the reduction in yields bids up their prices and makes their returns look good looking backward, but lower looking forward.

When you have several assets getting bid down toward the yields on cash and bonds, then the liquidity starts spilling out elsewhere.

There’s also the material risk of asset bubbles. “Emerging tech” has been the main bubble in recent years.

The long duration nature of their cash flows make them especially dependent on interest rates being low. This means that they don’t have a ton of current earnings (or they may be losing money), but investors are paying up for the prospect of future earnings. Tesla is a good example of this, but it affects many companies.

Some call it the “everything bubble” just because the liquidity flowing in has been unprecedented. If interest rates are suppressed through debt monetization and currency devaluation, naturally there will be high prices in virtually everything that an interest rate is priced on.

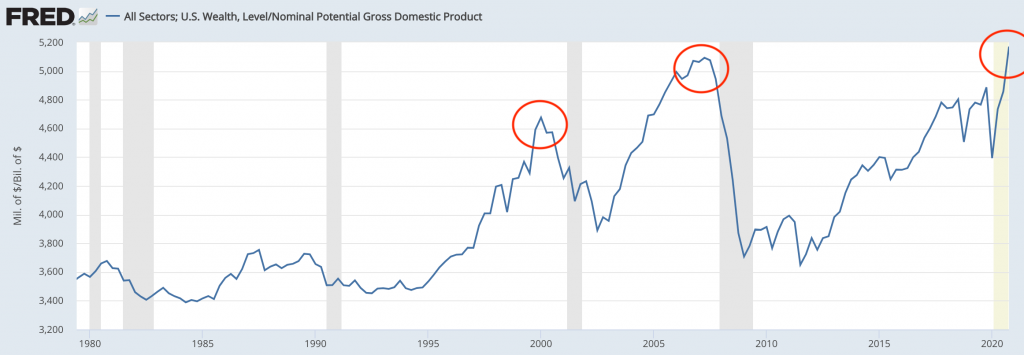

The chart below compares US wealth as a proportion of nominal GDP.

Tech Bubble (2000) vs. Housing Bubble (2007) vs. “Everything” Bubble (2020s)

(Sources: Board of Governors; CBO)

When rates rise, bonds and other yield instruments start competing with the riskier, long-duration securities for investment.

All the spending from the government and all the spending that will come out of savings rates coming down is potentially quite inflationary.

The huge debt overhang is still a huge deflationary force, so there are the competing forces and it’s not clear-cut what happens with inflation.

But if you’re owning bonds at very low levels – anywhere from minus-1 percent to positive-2 percent interest, depending on where you go in the developed world – there’s a risk.

You don’t have much upside, but you do have a lot of downside if inflation picks up and/or real interest rates go higher.

And the bond yields are supportive of the stock market. So if you get a downturn in the bond market (higher yields), then you’re taking away the pins supporting the high levels in the equity market.

There are certain parts of the stock market that would do better than others in this scenario – e.g., consumer staples – but the more indebted sectors and the emerging tech stocks that depend on the super-low rates for their valuations could especially suffer.

The NASDAQ will do worse than the S&P 500 in cases of a bond sell-off/higher rates because of the greater mix toward tech – i.e., lower amounts of current earnings, higher amounts of discounted future earnings.

So the bond market is a real issue for the market and will be for a long time.

Either:

a) Yields rise and there are periods where bonds and stocks fall together.

b) The government comes in to buy up the surplus of bonds. It could be a type of implicit or explicit yield curve control type of situation. This is a negative for the currency, as it involves creating money to cover the debt to effectively monetize it.

General risks

The biggest risks are the ones you’re not aware of or can’t see. If you can see a risk, others probably can as well, and you’ll probably be motivated to do something about it.

And it’ll probably, but not always, get baked within the pricing.

It’s what you don’t know and have great difficulty anticipating that’s generally the problem.

For example, there are different sources of bubbles, each relating to how purchasing power is conveyed (money and credit).

One is a debt issue. A lot of credit gets created and that goes into assets. The cash flow isn’t there to service the debts and the value of the assets eventually needs to come down, which impacts net worths, creditworthiness, and then incomes.

Another is a money-driven bubble. At zero interest rates and a lot of money creation, there’s a lot of it sloshing around.

When there’s a lot of money and it’s not tightened through higher interest rates and there aren’t the productivity rates to support that level of money in the system, then it loses value. Everything boils down to productivity. It’s what gives money its value, as money is a proxy for the value of economic activity.

One of the big risks for most traders and investors is relying on the past to inform the future when we’re really in a new type of environment.

It’s uncommon to see rates at the zero lower bound and it’s the most important thing to understand. Not just zero percent cash rates but also negative, zero, or near-zero bond yields.

When rate cuts can’t help offset declines in markets and drops in the economy, and the lack of further upside in rates doesn’t give the diversification it once did, that’s a big risk to traders and investors who are heavily concentrated in stocks or 60/40 stocks/bonds type of portfolios.

With the way that US stocks have performed since the financial crisis or even since the start of the American world order in 1945 if you want to go back that far, it’s common to extrapolate that.

It’s easy for someone to say just hold an S&P 500 or NASDAQ index fund and you’ll be fine, and you don’t need to do anything fancy.

This is simply because it’s worked for so long to the point where the reasons behind why it’s worked for so long don’t get scrutinized to see if they’re still logically applicable.

Trading and investing isn’t a closed system like chess where you know what worked in the past will work in the future. There’s little you can be sure of outside:

a) financial assets will outperform cash over time, and

b) different assets will do well in different environments

If you were a 60-year-old American in 1933, your adult life had been characterized by various “panics”, recessions, a major world war, and debt busts (e.g., 1893, 1901, 1907, 1913, World War I, 1920, and 1929-33) and you may have thought that stocks were extremely flighty and simply not worth the risk.

After all, you had just seen them lose nearly 90 percent of their value over the past few years and multiple episodes that were still in your memory based on your life experiences.

It was at that point, however, that made them essentially the buying opportunity of the century just because of how cheap they became. 2009 was another example. 2020 was another once-a-decade buying opportunity.

It may have been very painful to buy at those lows given the market volatility and recent steep drops, but their big drops helped expand out risk premiums and increase their expected forward returns.

Many of today’s traders and investors have only seen things like cryptocurrency go up in extreme ways – and, to a lesser extent, some types of stocks that perform in a similar manner. This impacts what kind of risk appetite they have. When you’ve mostly only seen big gains you tend to be less cautious.

The cause-effect drivers are what’s most important.

Still, with the way a lot of market activity is automated through AI and machine learning systems, much of this is based on what’s worked in the past rather than getting at the deep understanding of cause and effect. So, if past data is used in these models it still affects market action and therefore influences future data.

But at a certain point, you can see the standard approach of just putting everything in equities as being a potential wealth destroyer, given where interest rates are and meager productivity rates. It’s much more difficult to get quality returns out of them relative to when you have a strong interest rate tailwind and high productivity rates.

Short-term interest rates, US

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

When short-term and long-term interest rates are out of room – as they came to be in 2020 – it becomes more difficult as more of the policymaking mix shifts toward politicians.

Are they willing to help? And, most importantly, are they able to help?

Emerging market countries can rarely engage in much deficit spending. They don’t have reserve currencies. This means there’s little demand for their debt. So any material deficit spending can create a balance of payments problem and feed directly into inflation.

Sometimes when the gap is never closed, you can get hyperinflation, where practically everything is a store of value outside the domestic currency.

Money printing can still keep nominal equity returns high. But your returns are not just equity returns. They’re equity returns plus the currency. Money buys you less over time because of inflation.

So even if your nominal returns are good, does that mean your real (inflation-adjusted) returns are still good? Are you gaining enough extra purchasing from your investments?

Equities – at least certain forms of equities – can be good stores of wealth. For example, if they aren’t reliant on interest rate cuts to keep their values up and what they sell is always going to be in demand, it can be considered a quality store of value. The same can be said for the companies involved in helping create the big productivity advances.

But in this environment, holding only equities can be a very risky portfolio relative to holding various other stores of value that can help make it through all environments without suffering intolerable drawdowns.

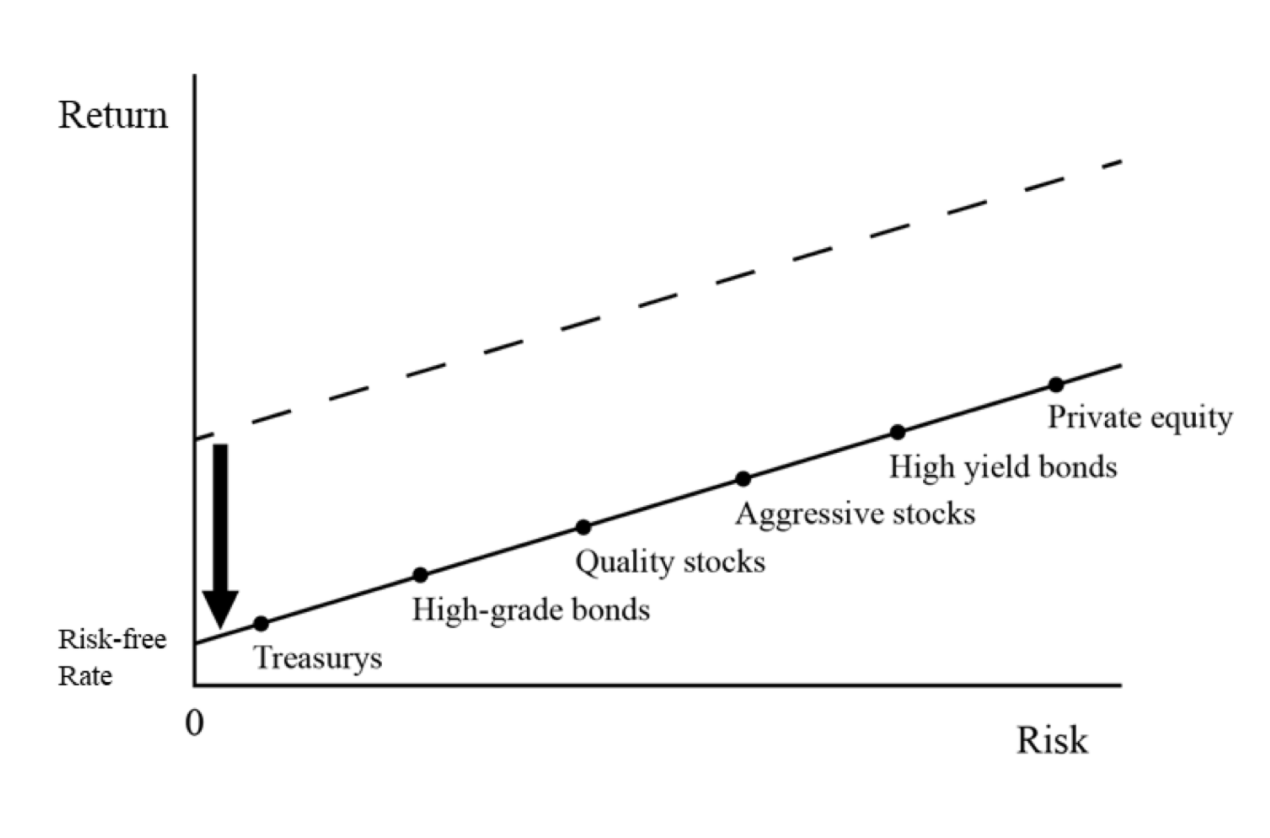

Any type of concentration is risky because they have big ups or downs depending on the environment they’re in. This is mitigated significantly if various assets that do well in different economic environments are sized and blended well.

It’s not necessary to go “all in” on a certain asset class when you can diversify among different asset classes and mix them well to produce a more optimized portfolio that can give you the same return for less risk, more return for the same risk, or some combination thereof.

When a portfolio has environmental bias, your expected distribution of outcomes is much wider.

Having a balanced portfolio allocation is a form of risk management and you can do this in a way that won’t constrain your long-run returns. This is the most common knock typically associated with diversification.

Everybody’s favorite asset class – whether that’s stocks, bonds, gold, commodities, and now you can consider cryptocurrencies and bitcoin, and so on – is going to draw down 50 to 80 percent or more during their lifetime.

Diversifying within asset classes and among different ones and balancing them well can materially help reduce drawdowns.

Usually whenever there are big gains in an asset class – stocks, cryptocurrency, and even standard boring bonds because they’ve worked for so well – there’s the aforementioned tendency for pricing to reflect an extrapolation of the past. The high returns are expected to continue even when the opposite is more likely to be true.

This can sow the seeds of the next downturn because of the leverage that tends to build in the system along with it.

And there’s always idiosyncratic risk to consider if you choose to remain concentrated.

For example, Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 and Archegos Capital Management in 2021 are instances of funds with large notional exposures causing big ripples in the markets.

Prime brokerages, which are typically investment banks that provide leverage and leveraged products to institutional investment managers, also took large losses associated with those blow-ups.

The market ended up moving not because of anything fundamental but because of the liquidity issues associated with a particular manager and the forced selling or covering that came with that.

It’s important for traders and investors to think about their exposures, what the risks are, what are intolerable, know what can’t be known, and do one’s best to get rid of them or be as immune to them as possible.

As a trader, you’re going to go through periods where you have drawdowns that you didn’t expect. Still, when you back up and look at those drawdowns, were they within the range of expectations?

You have to know the overall risk you’re taking on (volatility, concentration) and measure what’s likely through backtesting and other stress tests.

It’s always important to be mindful of what you don’t know and can’t know.

If your drawdowns are exceeding your expectations, then there’s likely information you’re missing or a process flaw holding you back from improving.

Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency vs. Bonds

The ultimate answer is that it can be both. Nothing has to be a 0-or-1 answer.

While nominal rate bonds are risky because of their very low nominal and real returns in the developed markets (i.e., US, EU, Japan) – though this is less true in markets like Southeast Asia – they can still have some value in a portfolio.

If all the deflationary forces in the world win out, nominal rate bonds will be useful to hold.

As for longer duration, store of wealth, contra-currency type assets, cryptocurrency can be a small slice of that. But you also have to be careful because they’re so volatile. Even 1 to 2 percent of a portfolio can represent plenty of risk in a portfolio.

(See: How much cryptocurrency should you hold in a portfolio?)

If and when cryptocurrency markets mature and there is more liquidity, a clearer regulatory picture, and a more diversified asset base that helps reduce their volatility, cryptocurrency can be more of a part of a portfolio without dominating its returns.

But there is no one answer. It has to a be a diversified answer to help you get to the other side of all the things that are going to be thrown at you on your trading journey over time.