Fed Put

The ‘Fed Put’ is the widespread belief that the US Federal Reserve (commonly referenced as “the Fed”) can always rescue the economy and financial markets. The term originates from the analogous comparison of selling a put option on the market.

The Fed has large-scale control over this process by being able to decrease interest rates or by injecting liquidity into the system in other ways, like quantitative easing (i.e., asset buying programs) or through coordination with fiscal policy.

Idea behind the ‘Fed put’

When one sells a put option, that provides the obligation to buy a stock or other security at a predetermined price if the buyer of the put option wants to sell it to you.

Similarly, when a central bank is easing monetary policy, it may have an idea of how low it is willing to have the financial markets fall before intervening with liquidity measures to help support asset price valuations.

In the early stages of a market downturn, the drop in financial asset prices has a bigger effect on economic activity than the actual events going on in the real economy.

This is because financial assets are a big component of wealth, so a drop provides a negative feed-through into the economy.

Financial assets are also a form of collateral. That means higher asset prices help companies and people become more creditworthy. This enhances their ability to borrow, take out credit for various purposes, and refinance debt.

Credit conveys spending power. If people have less collateral and are less creditworthy, this means spending is cut. One person’s spending is another person’s income. So, incomes drop in conjunction.

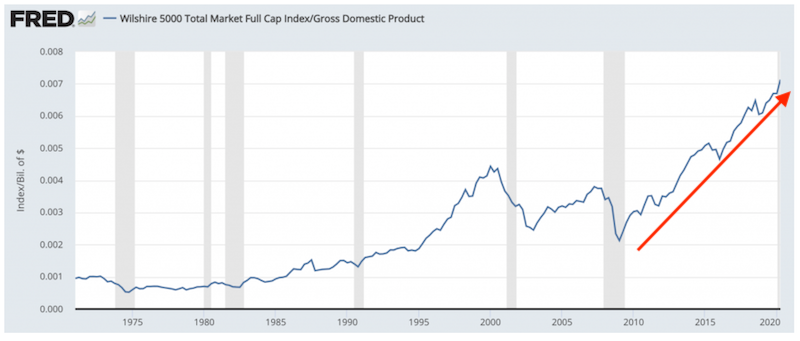

Asset prices have become an even more important part of an economy. The Fed’s actions to support the economy in previous big downturns (e.g., 2008, 2020) boosted their earnings multiples. Their values have become an even larger component of GDP.

Market cap to GDP ratio, US

(Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Wilshire Associates)

As economies remain highly indebted relative to their level of income since 2008, policymakers have had to boost asset prices to keep long-term interest rates very low.

Because of additional weakness, certain forms of corporate credit have also been bought. Central banks will always try to backstop as much collateral as they need to in order to support the economy, even if it means going down the quality ladder.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the ‘Fed put’ meant buying US Treasury bonds and government-backed securities.

How it works

A ‘Fed put’ is generally thought of through the interest rate mechanism.

Lower interest rates help stimulate investment by businesses and consumers and enhances the general consumption-wealth effect.

Zero interest rates help create a pull forward effect where people don’t want to miss out the lower rates by making purchases they wouldn’t have otherwise.

There’s also the impact on discounted present values. The value of a business is the amount of money that it makes over its lifetime discounted back to the present.

This discount rate is a required rate of return. Every investor has a certain amount of return they expect to return on an investment.

For example, if you want to earn 5 percent returns annually over ten years, if you wanted that money to equal $1,000 in ten years’ time, you’d need to invest $614. Five percent compounded over ten years would turn that $614 into $1,000.

When the Fed lowers interest rates, the expected returns of all assets fall in conjunction.

If the rate of return on cash or bonds goes down because the rate is lower, then the extra relative return provided by riskier assets looks more attractive by in relation. This causes market participants to move into those assets, bidding up their prices and lowering their forward returns.

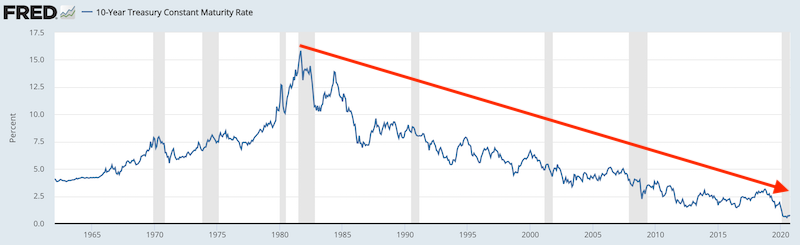

Accordingly, interest rates are a big component of the Fed put phenomenon. From a monetary policy standpoint, it almost always starts with lowering interest rates at the short end of the curve and going into longer term interest rates, if necessary.

Before, a Treasury bond may have given you that 5 percent. But these days, 5 percent is more likely for a stock.

So, you’d have to go from a very safe asset like a Treasury bond into stocks just to get the same yield. That, of course, means taking on materially higher risk.

That means more and more people rely on stocks and other forms of equities (e.g., private equity, venture capital, leveraged credit, real estate, non-traditional assets and non-traditional strategies) to accumulate and/or preserve wealth.

Therefore, a drop in the stock market can have a material negative wealth effect that could adversely feed through into the economy. This intensifies the need for a so-called Fed put.

If equities drop, it’s not only shareholders that lose money. Because business valuations decrease they become less likely to pursue investment opportunities, hire workers, make capital expenditures, and engage in other forms of spending.

This, in turn, makes consumers less wealthy. There is less spending and accordingly there’s less income.

Given the Fed’s statutory dual mandate of maximum employment within the context of real economy price stability, keeping an eye on asset markets and ensuring their stability becomes a type of de facto third mandate.

Moreover, given that quantitative easing (QE) runs directly through the financial markets – i.e., the central bank “prints” money and uses it to buy financial assets – the central purpose of this policy is to fundamentally increase the value of asset prices.

When the central bank has put in place accommodative monetary policy in the form of low, zero, or negative interest rates and quantitative easing, the expectation is that the ‘Fed put’ will hold either by making policy even more accommodative or through temporary liquidity injections to help prop up the market.

The ‘Fed put’ as it applies to other central banks

The Fed is, of course, not the only central bank that backstops its markets. Practically all countries with a reserve currency will do what they can.

When a country has a reserve currency, it means other countries save in it and transact in it to an extent. In other words, there is more demand for the debt in that currency.

So, if a country runs into financial stress and needs to borrow to plug a gap, it won’t have the same issues in comparison to a country where there’s little savings or business done in its currency.

With a reserve currency, borrowing exerts less upward pressure on interest rates and/or depreciation pressure on the currency.

For example, most of the EU is on the euro, the world’s second-most reserve currency after the US dollar.

Beyond its semi-traditional policy tools like interest rates, the ECB as part of its own “put” can loosen rules on the types of bonds its willing to buy.

Rather than only certain national and corporate bonds that meet a certain quality, any issuance pertaining to the EU Recovery Fund can be offset by the ECB buying it. Riskier corporate bonds could be purchased as well.

The case of the UK

The current situation of the UK economy is an interesting case. It’s a developed market country pursuing aggressive monetary policy, but it’s more constrained than other countries in how far it can go.

The UK has the advantage of being on its own independent free-floating currency unlike most of the rest of developed Europe, which adopted the common currency.

That means the UK has an advantage where it can pursue monetary policy in light of its own conditions.

However, the UK doesn’t have the same “printing power” as it’s less of a reserve currency than the USD, EUR, and JPY.

Measuring all global FX reserves together, the GBP is 4-5 percent of them. There is not as much savings or usage of the pound relative to the dollar or euro, and slightly less relative to the yen.

It’s somewhat of a reserve currency, but it’s likely to “hit the wall” sooner given the limitations in how much debt it can issue before this pressure goes through the currency or in the form of higher interest rates.

Other central banks in the main three reserve currencies (USD, EUR, JPY) should find the Bank of England’s situation as a type of case study in terms of the inflation risk.

Buying stocks

A central bank can also buy stocks if it really needed to depending on what the laws are in each jurisdiction. But past a point, the marginal positives that come out of “printing” money to buy progressively riskier financial assets isn’t much once longer term yields are close to short term cash yields.

Really the goal boils down to helping finance spending in the real economy.

If the Fed is buying stocks, that mostly helps those who own them. They also tend to be wealthier individuals who have lower propensity to spend as a whole.

That means at a point, fiscal and monetary policy coordination will provide more benefit. In basic terms, fiscal policy distributes capital while monetary policy provides the financing.

Yield curve control

Other central banks like the Bank of Japan and Reserve Bank of Australia also use yield curve control.

This guarantees that the government can finance spending at a fixed rate of interest at a certain duration (e.g., 3 years, 10 years). It’s a way of controlling interest costs and preventing debt servicing from exceeding income growth.

The US previously engaged in yield curve control to finance World War II spending from 1942 to 1947.

The Greenspan put

The original ‘Fed put’ phenomenon was classified as the “Greenspan put” in reference to then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan lowering interest rates in response to the 1987 stock market crash and increasingly popular after the 1998 blow up of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM).

Greenspan’s realization of the importance of the financial markets to the economy preceded that.

In general, “financial people” think differently from traditional economists (who comprise most central bankers).

While central bankers tend to focus on variables like employment and business investment, financial types focus on debt, asset prices, and cash flow and have views that are more closely molded by trading experience rather than formal economics training.

Over the course of Greenspan’s time at the Fed, whenever the stock market entered a bear market (dropped by more than 20 percent), the Fed would lower the fed funds rate.

At certain points, this would make cash and lower-duration bonds unattractive relative to riskier assets like stocks.

Lowering interest rates encouraged lending, which facilitates risk-taking and help avoid further declines in asset prices.

The Fed put created fears that if traders don’t have a healthy fear of risk, they tend to take outsized risks.

Namely, there is the high upside potential without respect for the downside risk because someone else is absorbing it – e.g., the currency (central bank money printing), the taxpayer.

There was also a ‘Fed put’, or central bank intervention, during the following economic events or crises:

- savings and loan (S&L) crisis of 1990-91

- the Gulf War (1991)

- Mexican peso crisis (1994)

- emerging Asia financial crisis (1997)

- Russian default (1998)

- the aforementioned LTCM insolvency (1998)

- Y2K (1999)

- the bursting of the dot-com bubble (March 2000)

- September 11 (2001), and

- the 2008 financial crisis

With this implicit Fed support, this has aided higher asset prices, helped narrow credit spreads, and made asset bubbles more likely.

Though people like rising asset prices, asset bubbles are essentially like any other form of indebtedness. Companies fundamentally have value because they earn a certain level of income.

Economic earnings at a certain level need to transpire in order to validate their prices.

With the cost of steep drops in asset prices on the economy in combination with lower real growth rates in developed markets, this likely means that central banks will have a tighter “put” on the market than normal and have to tolerate higher inflation. This will help get nominal growth higher.

And as real yields decline, this will force investors increasingly into riskier assets like private equity, venture capital, riskier lending, emerging markets, and so on.

Limitations of the Fed put

The general way things have worked in a market and economic downturn is through the lowering of interest rates.

Generally, an economy “overheats” once there’s excessive inflationary pressure. There are three general things that an economy is made up of:

i) labor

ii) commodities and raw materials

iii) capital

Therefore, recessions are typically, but not always, caused due to unhealthy price pressure in one or more of these. (Recessions and disruptions in economic activity can occur for many different reasons outside of a tightening in monetary policy, such as droughts, wars, and so on.)

The general cause of inflation is when the demand for something exceeds the supply of it. This is true for price growth in anything, whether it’s workers, commodities, stocks, money, etc.

Often this happens with labor, where there’s not enough supply relative to demand. This causes corporate cost structures to go up, which results in price pressures in goods and services.

At a point, the positive impact from a lower unemployment rate is not enough to offset the price pressures in goods and services because the relationship is non-linear.

So, the central bank raises interest rates to tighten money and credit. The markets decline and the economy follows sometime after.

As the trade-off between growth and inflation becomes more acute during the latter stages of the business cycle, the odds of a policy error increase.

This is especially true when a country is running fiscal and current account deficits.

It is popularly known among traders, investors, economists, and other market participants that central banks face the trade-off between output and inflation when they change interest rates and liquidity in the financial system.

What’s not as well known is that this trade-off is more difficult to manage when capital is leaving the country (and conversely, easier to manage when capital is coming into the country).

Capital flows coming into a country allow it to increase its foreign exchange reserves, lower interest rates, and/or appreciate its domestic currency depending on how the central bank wishes to use this advantage.

When capital moves out, the central bank’s job is accordingly more difficult. It faces either higher interest rates, a weaker currency, and/or will need to expend its finite supply of FX reserves.

In a capital outflow scenario, less growth is achieved per each unit of inflation.

To offset the drop when the market and economic outcomes become too painful – i.e., a type of Fed put, if you will – the Fed cuts interest rates.

This is the general dynamic.

In modern times, with interest rates very close to zero, it’s different.

When nominal interest rates can’t be lowered because they’re already at zero or slightly negative, this is where the government will step in as the lender of last resort.

It effectively has to reassure investors that policymakers will come to the rescue to, in effect, save the system.

They will effectively guarantee that large amounts of money and other forms of support (e.g., bridge loans, grants, and types of liquidity) will be made available to various companies and players in the economy and that they can rely on a quick recovery.

Typically, however, this support is not promised fast enough.

Though the government knows it needs to provide a “put” to the markets and economy, the initial lack of sufficient action causes painful losses before this support is given.

In most financial crises, certain entities are vilified by the public because they’re believed to have contributed to economy-wide pain.

Moreover, in a capitalist system, policymakers prefer to have certain entities bear the consequences of their choices.

They also need to be mindful of trade-offs and the cost of what bailouts for certain entities might mean.

There’s also the issue of moral hazard, which can incentivize greater risk-taking under the belief that the gains are privatized and the losses are socialized.

Nonetheless, once it becomes clear that the cost of not providing support is greater than the cost of providing it, policymakers inevitably come in to do everything they can to rectify the situation.

The markets may indeed fall quite a bit in the interim and cause a lot of companies, people, and other entities to go broke before they come in to trigger the ‘Fed put’.

It’s at this point, when policymakers become aggressive enough through the lowering of interest rates, buying assets, and other credit and liquidity support measures that investors can begin to see that capital markets will recover.

Fed put in an era of zero interest rates

When short-term and long-term interest rates are at or around zero, that mean the Fed put must take on a different form.

No longer can central bankers simply cut interest rates to get a bottom in markets and then the economy.

With the primary and secondary forms of monetary policy out of gas (interest rate cuts and QE), the central bank has to turn to the third main form, which is a coordination between fiscal and monetary policy.

The move would have happened eventually with the large amount of debt coming due, along with debt-like liabilities in the form of pensions, healthcare, insurance, and other unfunded obligations.

The large drop in income experienced around the world from the virus produced very large fiscal deficits.

In the US, it meant a 5x increase in the annual deficit relative to GDP. Whenever there’s a funding gap, it has to be financed by central banks printing money.

This third form of monetary policy is simply to get money directly in the hands of entities to make up for lost income and avoid an elongated compression in economic activity. It is particularly useful if the money gets in the hands of those who will spend the money to help get the spending and income “flywheel” going again.

The byproduct of this is that there’s going to be zero, near-zero, or negative interest rates across the developed world for a very long time.

That means for most investors in developed countries who are focused on their own domestic markets, cash and most forms of quality bonds are largely not viable investments from an income perspective.

Fewer people want to hold an investment if it doesn’t yield anything in real terms. Even fewer will be willing to hold it if it doesn’t yield anything in nominal terms.

The BBB yield, which is one step above junk or “high yield” grade, provides only about 2.5 percent in annual yield.

(Source: Ice Data Indices, LLC)

After paying taxes and the impact of inflation, you’re taking that risk for practically no compensation in real terms.

The zero and near-zero interest rate environment across the developed world and the implications of what it means for the ‘Fed put’ is probably the single most important issue for today’s participants to understand.

They will need to learn how to manage money effectively in this new world without the ability to stimulate markets and economies in the traditional way.

The old ways of easing policy and having that create a boost to asset prices won’t work to the extent we’re used to.

Since 2008, due to the financial crisis, market players have been used to being around the zero lower-bound on interest rates in all the main reserve currency countries.

It was true in the US, the core EU countries including the UK, Japan, Switzerland, Canada, and Australia and New Zealand.

But the policies monetary authorities undertook to ease was simply lowering short-term rates, and when that wasn’t enough moving into lowering long-term rates through the buying of financial assets.

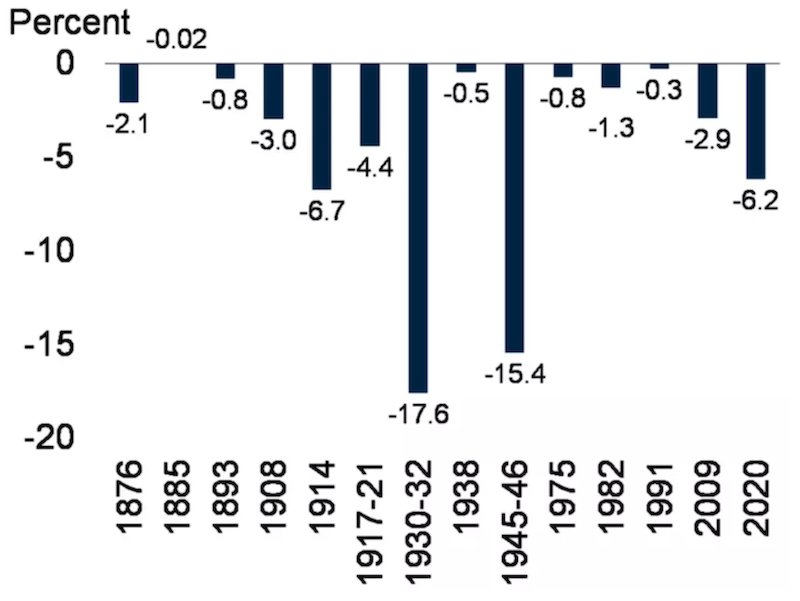

Global economic contractions since World War II

(Source: World Bank)

Monetary policy and the traditional capacity for a ‘Fed put’ is a lot less than the past with all rates being low on the curve with a decade-plus of buying financial assets and pushing down risk premiums in all financial assets.

Historically, most economic downturns are related to debt and liquidity problems. And these are typically (and primarily) remedied in one way or another through an easing of monetary policy.

Going back to the 1800s and looking at how governments rectified debt and market problems, they always eased.

Economic depressions tend to not last indefinitely because in one way or another those in charge of the process realize they need more money and credit in the system. This is true irrespective of what type of monetary system they’re on.

The main three monetary systems are commodity-based, commodity-linked, and fiat. In this day and age, we’re mostly on fiat. This has been true in the US since August 15, 1971 when President Richard Nixon unilaterally took the US off the gold standard. The relationship had been previously established in 1944 (after a previous de-linkage in 1933) under the Bretton Woods monetary system. The 1971 severance was related to the fact that were too many liabilities relative to the amount of gold available and there wasn’t enough gold to go around.

If they’re on a constrained monetary system, typically gold-based or bimetallic (gold and silver) and changing the convertibility of the commodity for the currency doesn’t work to put enough money into the system or stimulate sufficient credit creation, they inevitably sever the link with it and go to an unconstrained monetary system.

As for the value of money, it could end up depreciated. And it’s especially a risk when that currency isn’t a reserve currency in great demand globally. Or if a lot of money has been borrowed in a foreign currency, like they commonly do in emerging markets. Printing money typically causes a depreciation, which causes the foreign-denominated liabilities more expensive to service because their currency doesn’t go as far. This is similar to a big rise in interest rates.

But they will always want to ease to get a reflation in activity.

Hitting the zero interest rate bound to get a bottom under the markets and economy has never been a hard constraint even if it seemed like a new problem when it happened. This occurred in the 1930-1932 period in the US during the Great Depression and the 2008-09 period after the financial crisis when buying assets to lower long-term rates became the new policy.

Even if nominal interest rates can only go to around zero or a little bit below, the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) interest rates can go quite negative. (This also makes a case for an increasing bond allocation to inflation-linked securities rather than standard nominal bonds.)

On March 5, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt made the announcement of ending the link with gold and depreciating the currency to help reflate the economy. That gave banks the money they required in order to repay their depositors. Nixon’s announcement was similar, both coming on a Sunday to allow the markets to digest the news ahead of time.

There was the same type of big easing situation in 2008 with the US Congress and Treasury getting together to create the TARP program and going to quantitative easing when the traditional ‘Fed put’ arsenal (lowering of short-term interest rates was no longer effective).

The response was late and cost the main US equity index slightly more than 50 percent, but it was much more swift that the response after the October 1929 crash, where it took 3-4 years and an 89 percent drop peak to trough.

In 2012, with the European debt crisis, ECB chief Mario Draghi had a similar type of decision to make.

In March and April 2020, there were moves by the US Federal Reserve, US Congress, and Treasury Department to get more liquidity into the financial system and real economy with more asset buying and coordinated fiscal and monetary policy. The Federal Reserve created a lot of money and implemented credit support programs with the US Congress.

Others might think of this as the newfangled buzzword MMT (Modern Monetary Theory). But there is nothing modern about it. These types of measures have been going on for thousands of years since the dawn of monetized economies.

These are the types of measures you see happening over and over again when you have zero short-term interest rates and what policymakers do to easing monetary policy further to end the debt and liquidity squeeze to save their markets and economies.

Limitations of a central bank put in emerging markets

In emerging markets, policymakers have to think through what the domestic pressures are relative to the balance of payments pressures.

Virtually all emerging markets face domestic dislocations in periods of a global downturn.

If emerging markets want to spend higher than their incomes (which in turn can’t go higher than their productivity over the long-term), then it’s a matter of where they’re going to get that money.

Can they create the money domestically? Or do they have to bring in capital from international banks and investors?

Emerging markets tend to be limited in both cases. These countries are generally less stable in a variety of ways. So, these types of economies run into these constraints faster.

For any country, there needs to be some basic foundations in place in order to attract external capital and create domestic wealth.

Any investor doing due diligence will evaluate a country in the following ways:

– Is the country stable politically? Are there appropriate checks and balances to thwart authoritarian power that could be used in an unproductive way?

– Is corruption low? Will any contracts entered be honored?

– Is there a large respect for the rule of law?

– Are there private property rights and are they respected?

– What is the overall culture of the country? Is there a focus on hard work over leisure? Is innovation and commercialism viewed positively?

– What is the regulatory and bureaucratic environment like? Is it overly lenient or largely unregulated, is it fair and appropriate, or is it stringent and discourage business activity?

Many investment firms will look to develop measures to quantify how each country comes in various avenues (cultural, what they value, education, indebtedness, income, growth, and so on).

Only when these are in place to a sufficient enough degree will investors have the confidence that the positive “vital signs” characterizing each country and jurisdiction could create a hospitable investment environment.

To an extent, developing economies benefit from inevitable reflationary tactics going on in developed markets.

For example, in the US when the Fed and Treasury work together to add liquidity to the US economy, some of this money and credit also gets into emerging market assets. Investors look to get higher yields and overall returns in foreign markets that they can’t find domestically.

Emerging markets with more developed credit and asset markets will be able to deal with the crisis more effectively than they have in the past.

For example, the “BRICS” countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) account for around 45 percent of the global population, roughly 25 percent of global GDP, and approximately 20 percent of global trade. They can handle a big downturn in their economies better now than they were able to even 10 years ago as their domestic capital markets are more mature and liquid.

There’s still nonetheless a large difference between emerging markets and developed markets in how they can respond to a drop in market and economic activity.

For example, in the 2020 downturn, Brazil could be more aggressive in terms of what they could do fiscally to replace lost income. Countries like Russia and Mexico were willing to take more of a drop to their incomes and spending due to a lack of reserve currency with the ruble and peso. They had to have big recessions, and there are the matters of social tensions and conflict that occur when these problems emerge.

There are trade-offs like with everything in economics. Countries that are more aggressive in keeping incomes high through aggressive fiscal and monetary policies will see adverse pressure with their currency, balance of payments, and/or inflation problems.

Reserve currency countries are less susceptible to these issues so inevitably do whatever they can to save the system. Emerging markets will run into these problems faster because the debt created by these measures has limited demand globally.

So, you tend to see that dichotomy.

In trading and investing, emerging markets generally promise higher returns because they have so much catching up to do. They often accordingly have higher productivity rates, higher growth in their working populations, and higher inflation rates. This feeds into higher rates of growth in financial asset prices.

But the degree to which their central bank can effect a “put” on their markets is much more limited.

Moreover, many of their projects deal with infrastructure and building, which entails a lot of debt. This leads to more market volatility and larger boom and bust cycles.

Those who pursue more aggressive actions are more prone to taking a hit to their currencies (and/or greater currency volatility) and/or upward pressure on domestic interest rates relative to those who are less aggressive.

China does not have a reserve currency through the renminbi. But it is the world’s second-largest economy and one of the world’s main money and credit systems. Moreover, it still has room in its nominal yield curve to stimulate policy in the future.

China will also be learning from the situations of other countries that have less stimulation capacity should it land in a similar policy situation in the future.

What can undermine the Fed put

The Fed put has been easy to implement over the previous decades because inflation hasn’t been a problem.

But if inflation were to tick up to, for example, 4 percent in the US, above the Fed’s two percent (or two percent plus) target, can policymakers tighten policy a bit to alleviate this issue?

And can they do so without knocking over asset markets?

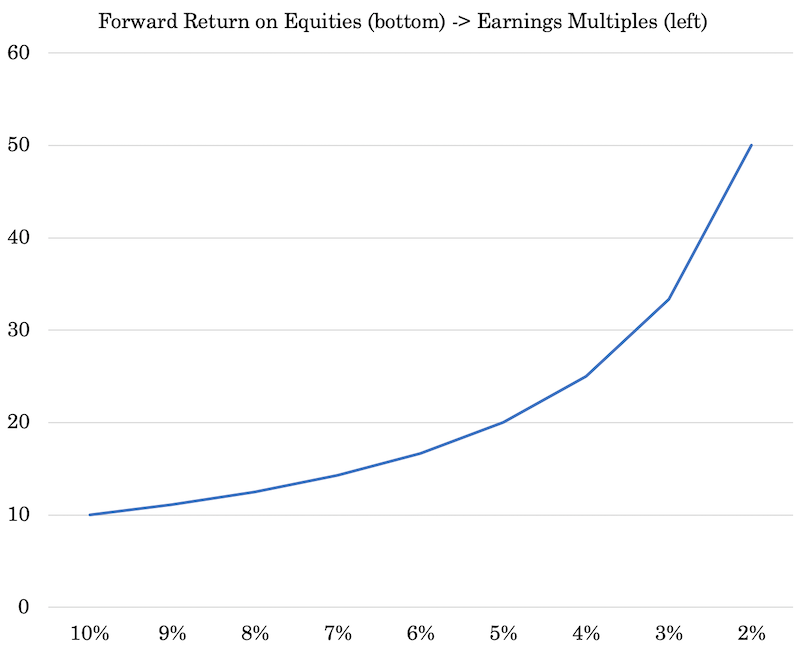

One issue that comes through very low interest rates is that the duration of financial assets lengthens in a non-linear way.

For example, if central banks employ a “put” to the point where the forward yield on stocks is only 3 percent, then a drop in prices such that they now yield 5 percent, makes the earnings multiples go from 33x (i.e., 1 over 3 percent) to 20x (1 over 5 percent).

That’s a drop in prices of nearly 40 percent, holding earnings constant.

On the other hand, if that two percent drop in yields goes from 8 percent to 10 percent, earnings multiples go from 12.5x to 10x, a drop of 20 percent in markets, holding earnings constant.

This shows the general relationship:

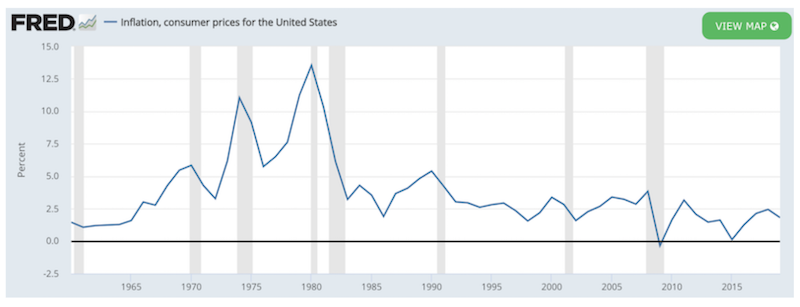

Right now, central bankers and traders aren’t very concerned about inflation, as disinflationary pressure has been the norm over the past several decades.

There are a few big influences that are part of this:

- High debt relative to income

- Aging demographics (which increases obligations relative to income, creating a squeeze on spending)

- Increase in the global labor supply

- As an extension of the above, offshoring to various cost-efficient places of production, a drag on domestic worker salaries

- Technology that helps increase economy-wide pricing transparency and reduce reliance on expensive labor

- A lesser role for organized labor

Central bankers have viewed inflation as predominantly a cyclical phenomenon.

In other words, as less labor market slack develops later on in a business cycle, this is likely to produce inflation. Conceptually this makes sense as a lower supply of something relative to its demand is likely to drive up prices.

Because of the various structural factors, central bankers have appropriately adapted their positions to view the various disinflationary elements (the aforementioned high debt, lower productivity, lower growth in the workforce, tech developments) as more influential on holding back inflationary pressures.

Nonetheless, lower growth and higher inflation is one of the big risks that policymakers face that undermines the continued support they can provide to the economy.

It also changes how traders might think about positioning their portfolios in the case inflation kicks up and the ‘Fed put’ is impaired by distinct trade-offs between further support to the markets and economy and cutting down on inflationary pressure.

If unacceptable inflation doesn’t pick up, then policymakers can focus heavily on getting growth back up in the usual ways – i.e., keep ing interest rates very low, buying financial assets, effectively monetizing fiscal deficits, and maintaining and/or expanding credit and liquidity support programs to the extent they’re needed.

Fed policymakers, and monetary authorities in other developed markets, will also accept a level of weakness in the dollar.

This is because a lower currency is good for borrowers relative to creditors. When you have a lot of debt, you generally want a weaker currency because it provides relief.

This is especially true with external debt levels are at over 40 percent of GDP, as it is in the US.

External borrowers that are unhedged benefit when their dollar-denominated liabilities fall in price relative to the assets they have denominated in their domestic currency. It’s similar to the same effect of a drop in interest rates or further monetary easing.

If inflation materially ticks up, then that can be a big inflection point for markets and a big deal for the notion of a Fed put.

The bias in where to take monetary policy is no longer as straightforward when you have those kinds of trade-offs involving inflation.

At the macroeconomic level, inflation is one of the main two forces that drive markets, with the other being growth.

Based on market pricing, when there are very low yields across the board, it basically assumes that the Fed can practically get whatever it wants.

Stocks are high relative to expected earnings many years out because their yields in both nominal and real terms have become so compressed. Inflation expectations, as implied through the TIPS market (i.e., inflation-protected Treasury bonds), are at their lowest levels ever.

The 10-year breakeven inflation rate is still expected to remain below the lowest readings of the previous economic cycle that ran from March 2009 (bottom in markets)/June 2009 (real economy) to February 2020 (both markets and economy).

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

Despite the upside risks to inflation with a lot of liquidity in the financial system and some of the permanent supply-side ramifications that came out of 2020, these are fairly bearish expectations for inflation.

The deflationary elements are very large and embedded, but there’s a wide distribution in potential outcomes. Going out 10+ years is a very long time horizon to forecast.

The market believes that the Fed put is alive and well.

So far, that’s happened in the form of cash and bond rates having come down and mortgage rates and other lending rates coming down as well.

Other central banks in developed markets have been this way. The Bank of Japan, with its yield curve control, has held 10-year interest rates at around zero. Short-term interest rates are a bit below that.

The constraint to keeping the Fed put going is always the currency and inflation, as mentioned in previous sections.

If inflationary picks up before monetary policymakers achieve their goals then that’s going to tell the markets that central banks can’t always provide as much support when needed nor are they capable of getting exactly whatever they want.

This could mean getting inflationary pressure, and having to act on it, before:

– bringing unemployment numbers back below 5 percent and/or

– getting a healthy positive growth rate with low and stable inflation

As a result, traders will need to think ahead to what an inflationary uptick would mean for markets and the notion of a Fed put before central bankers accomplish their desired goals.

This essentially applies not just to the US, but practically to all central banks and all markets.

Companies whose revenue and earnings are tied to the digital economy and long-duration assets that do well in a reflation may see an opposite reaction if the Fed and other central banks are forced to repeal some of its easy policy measures.

How will cyclicals (e.g., autos, industrials, steel) do relative to consumer staples?

How will commodities do, which generally perform well in an inflationary environment? Easy monetary policy is generally a net plus for commodities as they run in higher demand, but also may follow the general trend in equities if monetary policy has to tighten.

Would this mean nominal bonds will sell off?

Are inflation-linked bonds are a better choice, as you receive the inflation rate and there is no limit to how low real interest rates can go, unlike nominal rates?

Gold will tend to rise off the prospect of inflation and/or currency issues, as it’s simply a type of asset that functions as the inverse of money.

Gold will have tailwinds if real interest rates remain low or negative. Though gold essentially yields nothing, investment decisions are commonly made on a comparative basis. If yields on cash and bonds are zero and the inflation rate is two percent, then the real yield is minus-two percent.

That makes a no yielding asset like gold more attractive as a store of wealth.

Currencies generally depreciate in value when the cash and bonds denominated in them don’t yield anything and the central bank has to print a lot of money to deal with its debt problems and other obligations coming due.

Gold will inevitably have higher demand.

Individual policymakers are likely to do, and prefer to do, different things. Central banks have so-called “doves” and “hawks”.

The doves generally are more likely to let inflation run a bit higher if it means getting more worker into the labor force. Investors tend to like them better because holding interest rates lower or having a general slant toward easy policy is good for assets.

Hawks are generally less tolerant of higher inflation, believing it’s too destabilizing to the entire system.

Policymakers within the Fed and other central banks is more or less on the same page currently – namely, do what it takes to save the system, or effectively dovish.

Nonetheless, if unemployment goes down to only seven percent and inflation hits four percent, then the trade-offs are more acute.

This is how monetary policy was in 1970s where the unemployment and inflation trade-offs were not as straightforward with a lot of labor market slack and high inflation.

(Source: World Bank; St. Louis Federal Reserve)

Some denounce the idea of a Fed put as being too generous to financial markets, which can set the stage for asset bubbles and financial instability.

It’s easy during certain periods, particularly in retrospect, to criticize policymakers for letting policy be too easy and allowing inflation to spiral upward. But the trade-off between weak economic activity and high inflation is not easy to make, as neither outcome is particularly appealing.

In 1981, when Fed Chairman Paul Volcker decided the US’s double-digit inflation rate was no longer acceptable, the central bank made the unpopular decision to hike interest rates above inflation. This pushed real interest rates into positive territory. This was bad for practically all asset prices and the economy.

It helped get rid of the inflation, but it also put the economy in a recession.

However, in retrospect, it was the right move. The US faced disinflationary trends in the 40 years since, providing a long bull market in bonds and low double-digit annual returns in equities.

Fed Put FAQ

How can you determine where the Fed put is?

This is where central bankers words can be important.

For example, in May 2022 when the stock market had fallen about 20 percent to reach bear market territory, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell had this to say:

“This is not a time for tremendously nuanced readings of inflation. We need to see inflation coming down in a convincing way. Until we do, we’ll keep going.”

On the other hand, in Q4 2018, when the S&P 500 fell 20 percent, the Fed reversed course because inflation was not an issue.

When inflation is a lingering issue and a problem beyond growth concerns, the Fed is likely to continue tightening monetary policy.

Always look at where the inflation rate is – the Fed has an official target rate of two percent – and how that compares to economic growth and financial conditions (stock prices and bond yields, most notably).

A tightening in financial conditions comes about when stocks fall and/or bond yields rise.

If Fed policy is too easy, it can lead to asset bubbles.

Thus, the Fed put is not just about stocks but also about preventing imbalances in the economy that can lead to financial instability.

Is the Fed put real?

The Fed put is a real thing. It exists.

The financial economy leads the real economy. So if there is too much weakness in asset prices, they will need to pay attention.

If people have less wealth, there is less spending. If companies have lower stock prices, this usually leads to layoffs.

While it may not be an explicit policy, it’s pretty clear that central bankers will do what it takes to support asset prices and prevent any sharp declines.

This was evident in 2008 when the Fed injected trillions of dollars into the financial system through quantitative easing (QE) and other emergency measures.

It was also evident in 2018 when Jay Powell reversed course on tightening monetary policy pre-emptively to stamp out inflation from a tight labor market.

In the long run, Fed policy should be geared toward achieving financial stability.

Asset prices are important for growth and inflation, but they can also get out of hand and lead to imbalances in the economy.

The Fed put is a way to prevent that from happening.

When asset prices fall sharply, it can lead to a loss of confidence and a decrease in spending. This can then turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy where businesses cut back on investment and hiring, leading to a recession.

The Fed put is meant to stabilize asset prices and prevent these sorts of market corrections from happening.

Of course, the Fed cannot always succeed in this goal. But financial markets are something that they are aware of.

Markets provide key signals of where the economy may be going.

Where does the central bank get its money?

The Fed itself creates money.

As for how the Fed funds itself, it gets its money from the Treasury. They have what’s called a ‘revolving account’ with the Treasury.

The Fed pays for its operations with the interest it earns on government securities and other investments.

It also gets revenue from the services it provides to depository institutions, such as check clearing, electronic payments, and currency services.

The Federal Reserve does not receive funding via the congressional budgeting process. Therefore, the Fed is not taxpayer funded.

Can the Fed lose money?

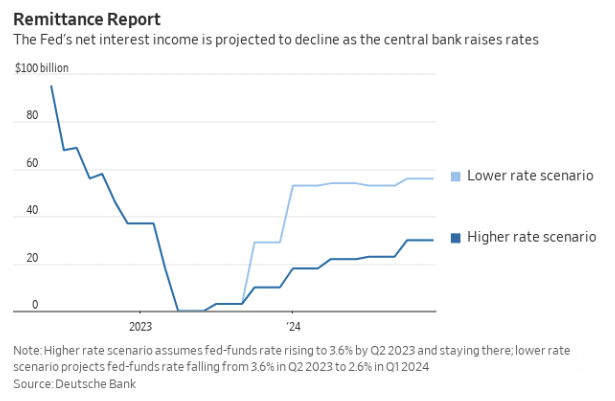

The Fed’s plans to raise interest rates aggressively to combat high inflation could have an overlooked and uncomfortable side effect for the central bank: capital losses.

The potential for losses hinges on obscure monetary plumbing.

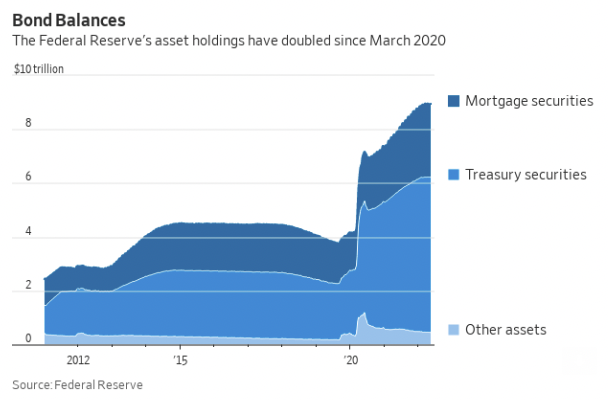

The Fed’s $9 trillion portfolio, sometimes called its balance sheet, is full of mostly interest-bearing assets (Treasury and mortgage-backed securities) with an average yield of just above two percent.

The other side of the ledger is the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet. These are bank deposits held at the Fed known as reserves, which also bear interest, as well as currency in circulation.

For more than a decade, the Fed earned more money on its securities than it paid to banks as interest on reserves because of relatively low short-term rates.

But if the Fed now has to raise interest rates a lot to fight inflation, they’ll likely have losses.

When exactly that occurs depends on the level of rates and the size of the balance sheet.

For now, that break-even level of the Fed’s benchmark rate – i.e., the point at which the Fed would pay more in interest than it earns – is around 3.5 percent, according to projections from economists at Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley.

What is the Fed’s balance sheet?

The Fed’s balance sheet shows all of the assets that it owns and liabilities that it owes.

The Fed’s assets include government securities, foreign currencies, and loans to depository institutions.

The Fed’s liabilities include currency in circulation, bank reserves, and capital paid in by member banks.

What is the Fed’s monetary policy?

The Fed uses monetary policy to influence the supply of money and credit in the economy.

The Fed can use three tools to implement monetary policy:

- Open market operations

- Reserve requirements

- Discount rate

Open market operations are when the Fed buys or sells government securities in the open market. This adds or subtracts reserves from the banking system.

Who is the owner of the central bank?

The Fed is owned by the US government. The central bank is a quasi-public entity, meaning that it is not completely public nor completely private.

The Fed was created by an act of Congress and its main purpose is to serve the public good.

However, the Fed does have some independence from the government in order to carry out its mandate.

Final Thoughts

A put option by itself is a contractual obligation where its holder has the right to sell an asset at a certain price to the entity on the other side of the trade.

The put option can be exercised if the security or asset declines below the option’s strike price. This effectively insulates the holder of it from additional losses, similar to the way insurance policies work.

In the case of the Fed put – sometimes referred to as the Greenspan put, Bernanke put (after the chairman who followed Greenspan), Yellen put, or Powell put – the holder of it is implied to be all market participants. In particular, all of those long risk assets like equities, which perform poorly in a downturn in the economy.

The Federal Reserve is essentially the counterparty. Namely, they would help the market should it decline by a certain amount if there’s a big event for the economy (e.g., financial crisis) that has big implications for the market.

In other words, past a point, to save the markets and broader economy, there is an implicit or expected action to be taken by the Fed.