High Inflation Investing: How to Profit From Inflation

In this article, we’re going to cover high-inflation investing and how to profit from inflation.

First, let’s start with the basics.

Cash is the worst in an inflationary environment

Cash seems like the safest investment because its value doesn’t move around much. But over the long run it’s the riskiest considering where the value of money goes over time (consistently lower).

For example, $1 saved today will be worth the equivalent of just $0.78 within 10 years if inflation hits 2 percent (the inverse of 1.02^10). If inflation hits 4 percent, then that same $1 will be worth just $0.67 in 10 years time (the inverse of 1.04^10), or only about two-thirds the value.

If inflation were to hit 6 percent over 10 years, then a dollar today goes down to a value of just $0.55.

At a point it becomes intolerable, so central banks work to cool things off. But in the early stages, they lag it, often believing it’s transitory.

In a world of higher inflation, prices change faster than wages, so inflation erodes the value of savings from where they would have been had inflation been stable.

While wages going up because of productivity increases is positive. Wages going up because of pricing pressures mean those wage increases will be transmitted to prices, causing inflation.

Other issues with inflation

Inflation is also associated with asset bubbles that can burst and cause other financial crises. This is because a lot of the money and credit being created goes directly into financial assets, many of which don’t produce earnings or act as a very effective store of value.

Inflation in emerging markets makes debt hard to repay, because inflation reduces the value of currencies relative to debt levels even if interest rates remain steady.

The power of inflation to reduce the value of money over time is what gives inflation its corrosive force for savers (and lenders), especially in combination with modest returns on what assets are considered safe.

Most traders and investors are unprepared

Most portfolios are weighted heavily toward stocks and bonds and some cash. Bonds do poorly in inflationary environments. Stocks often have issues as well because inflation can cause interest rates to rise, hurting their values.

Bonds and stocks diversify well with respect to shocks in growth, but not inflation.

For that reason, other assets are needed to help diversify well in an inflationary environment (commodities, real assets, gold, and others can have value).

If inflation is low, then there’s less need for inflation hedging or inflation protection.

But in terms of a portfolio, less important is the absolute level of inflation but the trend.

Asset prices respond most to “shocks” or “surprises” relative to what’s already discounted into markets.

Traders and investors should be mindful of inflation protection assets because they can help diversify portfolios away from stocks and bonds, which are not inherently diversifying.

And “high” shocks in inflation can hurt a portfolio just as much as the opposite.

High inflation erodes the value of money, while deflation can increase its value (in contrast with economies where central banks and fiscal policymakers have either kept tight monetary and fiscal policy or in cases where reduced interest rates and printed money have been ineffective in getting inflation higher).

Keep these concerns in mind because no matter what your investment goals are, protecting against inflation is just as important as the standard need to diversify against shocks in growth (as stocks and bonds portfolios do).

There are also rare cases, typically in emerging markets, where inflation is very high and increasing.

Hyperinflation cases

Hyperinflation is something that has its own playbook.

Cash and bonds eventually get wiped out. Equities tend to do a decent job of keeping pace in the early stages, but lag more as the inflation gets worse.

Getting out of financial wealth and into real assets is key in these circumstances. Inflation-hedge assets also represent buying power because inflation can devalue money and credit to zero in hyperinflationary environments.

This is why many governments like Bolivia, Russia, Argentina, and others keep large gold reserves and the asset is generally looked upon favorably in those cultures.

Some developed market governments, like the US and UK, provide inflation hedging instruments like TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) in the United States and inflation-linked gilts in the UK. These provide protection against one form of inflation (CPI).

Further reading: Hyperinflation: Definition, Causes, Examples, Remedies

Inflation: Building or fading?

For now, inflation is building, not fading. If demand is outstripping supply in a number of areas, inflation is produced.

This is true with respect to labor, housing, energy and raw materials, low inventories, among other things.

Thirty percent of CPI is housing – rents or imputed rents. There aren’t enough houses, which has its origins in the 2008 financial crisis, so that’s another endemic factor.

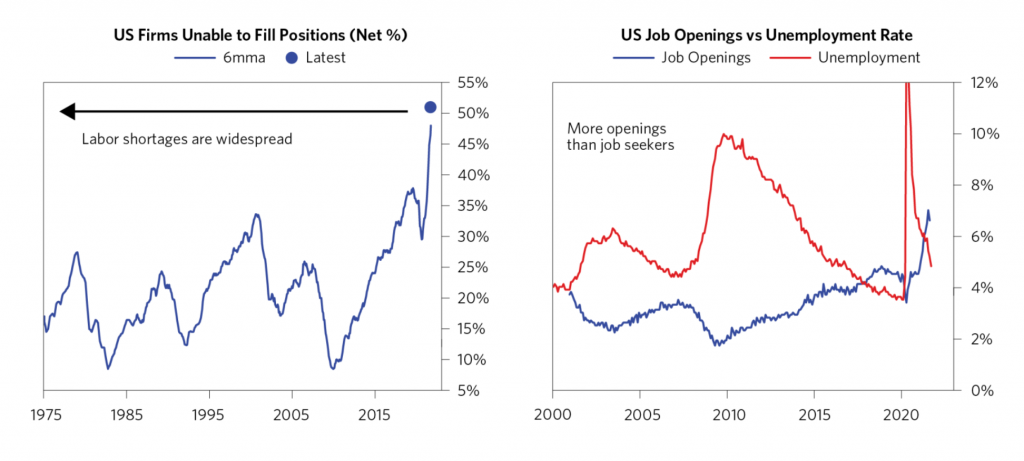

In labor markets, for example, there are more job openings in the US than employed people.

New policy

Aiding all this is the unification between fiscal and monetary policy that’s providing lots of money and credit (which the central bank creates) and fiscal policymakers directing it.

As opposed to policy that’s driven more through interest rates and QE/asset buying.

Interest rates work in managing the economy. But typically you need to drop interest rates by around 500bps in a normal recession to push enough credit back into the economy to get the bottom and subsequent recovery.

Interest rates help change demand. If rates are lowered, you increase demand, which changes spending, which changes income at the end of that chain.

But when interest rates are about zero, that’s out of room.

Post-financial crisis (2008), policymakers went to QE to lower long-term rates. That’s effective when long-term rates are high and liquidity is tight. But that’s also limited.

Policy currently is fiscal policy supported by monetary policy. Income is impacted first rather than last.

The cause-effect linkages are reversed relative to normal policy.

Instead of incomes going up at the tail-end of the process through changes in demand, it occurs at the front-end by putting money directly into their pockets.

Under normal policy circumstances, income is tied to an economic transaction. People work and create supply, which gets them money.

Instead, if more money is provided directly, it provides demand with no offsetting supply, which causes inflation to rise.

Pent-up demand

A lot of that liquidity didn’t immediately get spent.

In the initial rounds of policy, about one-third of the money that was sent out by the US federal government went into debt reduction. Another one-third or so was saved. Another third was spent.

So there’s still a huge reserve of liquidity that’s still in bank accounts waiting to be spent.

Policy unification requires a suppression of interest rates

The policy mold of the fiscal side spending money and the central bank creating money and buying bonds to support that policy also comes with the quirk of needing to suppress interest rates.

If you don’t keep interest rates down it’s like pressing the accelerator and brake at the same time.

What is means for traders and investors

The implication for traders and investors is that you get high nominal GDP growth but super-low interest rates.

The spread between nominal GDP and interest rates in the US is the highest since the 1960s and 1970s.

For investors and traders have that spread to capture by going long nominal GDP (i.e., forms of cash flow that mirror nominal GDP, such as certain types of equities) and short rates in case that spread compresses (which can, in turn, hurt the values of risk assets).

The question is then how much of that spending is real growth and how much of it is inflation. But for those in the markets, it’s just cash flow.

What brings this all back in line?

What brings all this back into equilibrium is the tightening of monetary policy.

We don’t have the ability to cut interest rates with where they are. But there is plenty of ability to raise them.

Then it’s a matter of how much of an increase and when.

If central banks and markets still believe inflation is “transitory” and that turns out to not be the case, then rate hikes will happen sooner than what’s discounted into markets.

Monetary policy is about the future path of inflation. Fiscal policy has to be viewed through that lens too.

Markets are still looking at this as “is inflation transitory or not?” through the lens of what’s worked in recent times, even though what we’re going through now is driven by fiscal stimulus. This diverts from the past when policy was driven more from the monetary side and fiscal policy was relatively tight.

There were deficits, but that compares spending relative to tax revenue, which is different from spending needs.

Hawks think there will be higher inflation and want to hike rates soon instead of later because inflation expectations might spike up with all the money people have in their pockets if they spend it unexpectedly fast.

We’re already dealing with significantly negative real rates (negative inflation-adjusted interest rates). This comes with longer-term issues like currency problems.

Negative real rates on a currency is not sound. It means that people will eventually want to get out of the currency because it doesn’t provide a good return. This makes it more difficult to control policy.

It also makes less sense going forward when economic demand is sound.

How much does it take to slow down an economy?

In normal times, it takes 300-400bps of rate hikes to slow an economy down.

And we’re in abnormal times. So much wealth has been created, and a lot of that is not real wealth.

But there’s so much money out there sitting in assets and sitting in assets waiting to get spent.

How to avoid getting burned by interest rate increases?

In this case, you want inflation-hedge assets. This is because the rise in interest rates is likely to lag inflation.

So this is likely to run through things like commodities, gold, and real assets before interest rates kick in to make those less attractive in favor of more traditional financial assets.

The first move up in interest rates is when they’re dragged up by the economy. That doesn’t put the brakes on everything right away. It just resets the levels.

And all the things that we’re describing about the United States and Europe are not the case for Asia.

Policy is still the standard interest rate-driven mechanism. They haven’t blown out their balance sheets to push money and credit into the economy.

While those in the US and Europe tend to have a very Western-centric view of the investment world, the “Asia bloc” – China and a mix of neighboring countries – have a total growth contribution that’s roughly 2.5x that of the western developed countries.

The sizes of the cash flows and credit outstanding are roughly equal.

Balancing a portfolio between East and West makes increasing sense but nobody is really even close to that. Most favor the West much more than the East.

The US is 20 percent of global output but about 60 percent of all investment assets. That’s sustainable in the short term but not the long term.

Will there be a ‘Volcker moment’ to contain inflation?

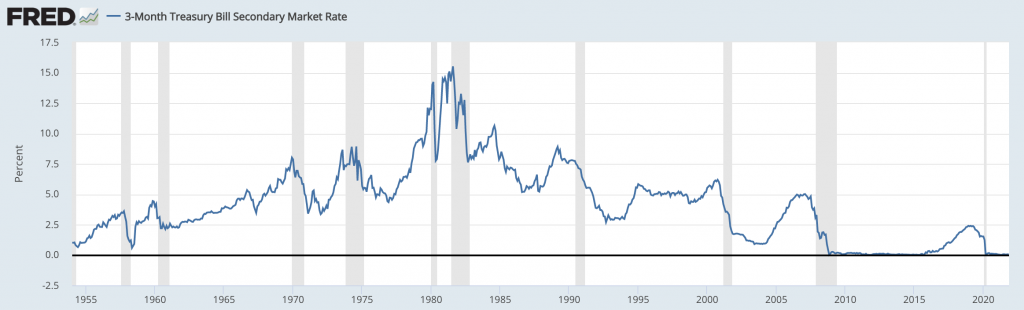

The inflationary pressures of the 1960s and 1970s were eventually rectified in 1981 when Paul Volcker increased interest rates to the highest level in the history of the US.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

That broke the back of inflation and led to a subsequent period of strong economic activity for around 20 years. Investment returns were great.

There was great pain when interest rates were raised to that level. Many entities got squeezed and effectively went broke.

While today the move is largely looked at favorably because it accomplished what it was supposed to, it was highly controversial at the time and bad for a lot of people.

Leading up to that moment, there had been about 20 years of inflation pressure, serious questions of the dollar as a reserve currency, and Volcker stepped in to put those questions to rest despite the trade-offs (the pain of a recession).

We’re at the beginning of a potential problem, but it’s got a long way to go to get to another prospective “Volcker” moment.

Inflation in charts

Here are various examples of why inflation is occurring.

Labor

Firms are having trouble finding employees, leading to shortages. There are more job openings than unemployed, placing more pressure on wages. (This is good if they go up due to productivity, but is less salubrious if they’re heavily inflationary.)

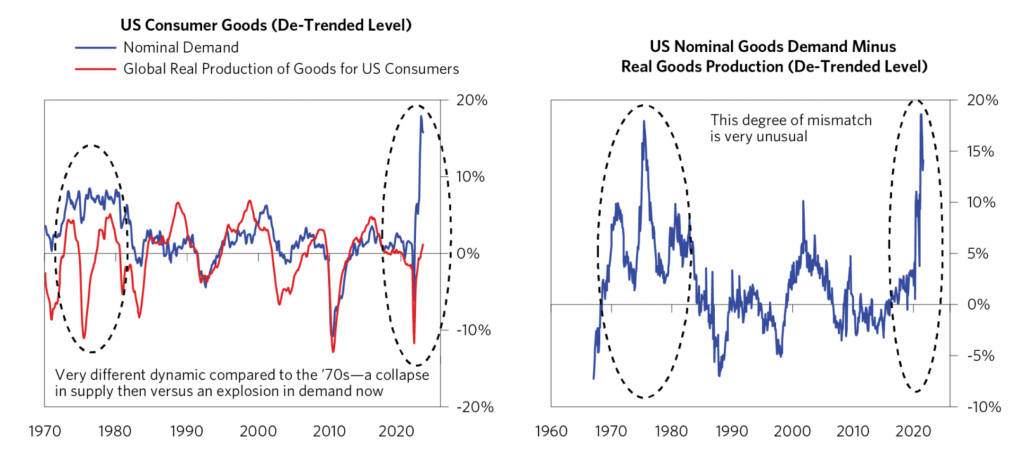

Goods inflation

Goods inflation is a consequence of nominal demand greatly exceeding global real production of goods. The level of mismatch is uncommon.

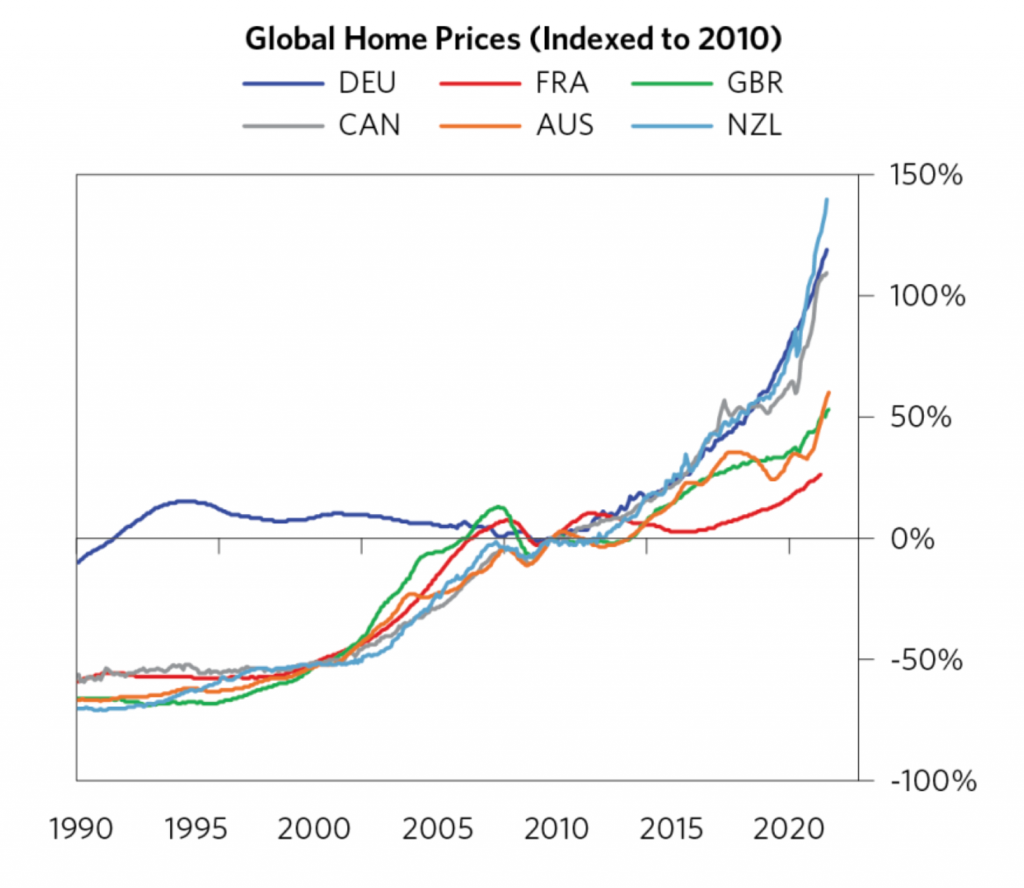

Housing

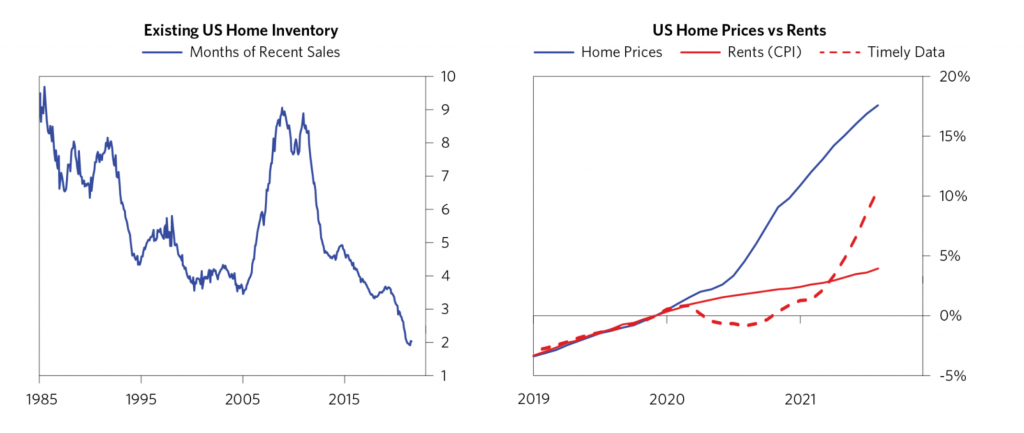

There’s a shortage of housing, which is a global phenomenon.

Home inventories are low. And low rates and lots of money and credit flowing into the system combined with low housing stock are pushing home prices well in excess of rents.

Goods inventories

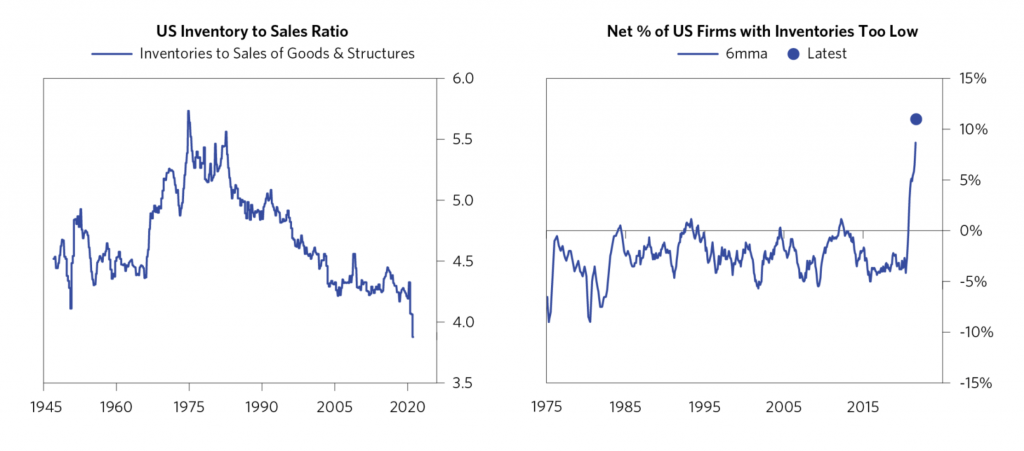

Inventories have been run down. Inflation can be masked at first if inventories are being used. But when inventories start to run low, then pricing pressure becomes clearer.

Conclusion

Inflation is likely not a purely transitory thing, but spreading. And this inflation is not just food and energy, but encompasses many things outside volatile parts. The inflationary pressures are starting to show up in other places besides the base components of inflation.

So if inflation shows up in health care, education, transportation costs (because oil prices go up), technology (where things like phones, video game systems, etc. are inflationary) then that means inflation is more endemic.

Inflation exists in housing – a third of CPI – because of demand and this component could be supply constrained for the next ~20 years due to the shortage of housing.

There has always been some level of inflation because low and stable inflation is targeted, but there is more pressure today than usual.

Policy actions feeding the process

Most think today’s policy landscape is very similar to something like the post-2008 policy mix. But they’re quite different.

If it’s not understood how they’re different (or it’s believed to be a supply thing, though supply is above 2020-start levels) then it’s going to be hard to understand why inflation is doing what it’s doing.

When both interest rate-driven policy and QE policy are effectively out of room, fiscal and monetary policies unify in those circumstances. Fiscal orchestrates the spending to target the money where it wants it to go and monetary policy supports that spending.

The Fed is choosing to support the current level of government spending by buying the bonds. If they don’t, interest rates rise, which would slow credit creation and nominal GDP.

In the current mix, with fiscal the dominant lever, income is the front-end of that process instead of at the back-end like it is under rates and QE policies.

A lot more money and credit have been put into the real economy directly that hasn’t been tied to creating supply (like the normal process). In other words, more income is not necessarily tied to a transaction.

So, accordingly, we’re more easily getting inflation. For a while, that can be masked by running down inventories so you don’t necessarily get it right away.