The Labor Market vs The Stock Market

The labor market and stock market are linked and we’ll go through the basic implications of how and why it’s important.

Basic overview

When there is lots of labor market slack – i.e., high unemployment – policymakers have great incentives to stimulate the economy with lower interest rates and other monetary and fiscal easing measures, if necessary.

This generally produces a strong period for asset prices. Even though the economy is still weak late in a recession and the early stages of the expansion, the stock market is generally back in a bull market. The financial economy leads the real economy.

Once you get to the late cycle and there’s little labor market slack, policymakers begin to slow things down, as they begin to fear inflation and financial instability (e.g., asset bubbles, too much credit creation).

Then they begin to take away policy support. So while the real economy tends to be good during this time, it starts to be a bumpier period for stocks.

Eventually they go too far in tightening policy because it’s hard to get the balance right. So there’s a drop in the stock market, followed by a drop in the real economy,

This then reverses when interest rates are cut and/or other monetary and fiscal easing measures are put in place to rectify the imbalance.

For that reason, we can say that the health of the labor market is a contra-indicator on when it’s best to buy stocks.

When there’s high unemployment you can generally feel pretty good about the forward direction of stocks assuming policymakers are skillful and have the power to make the necessary measures to provide support to the economy.

Conversely, when there’s low unemployment, it’s prudent to be more cautious about stocks as policymakers begin withdrawing support.

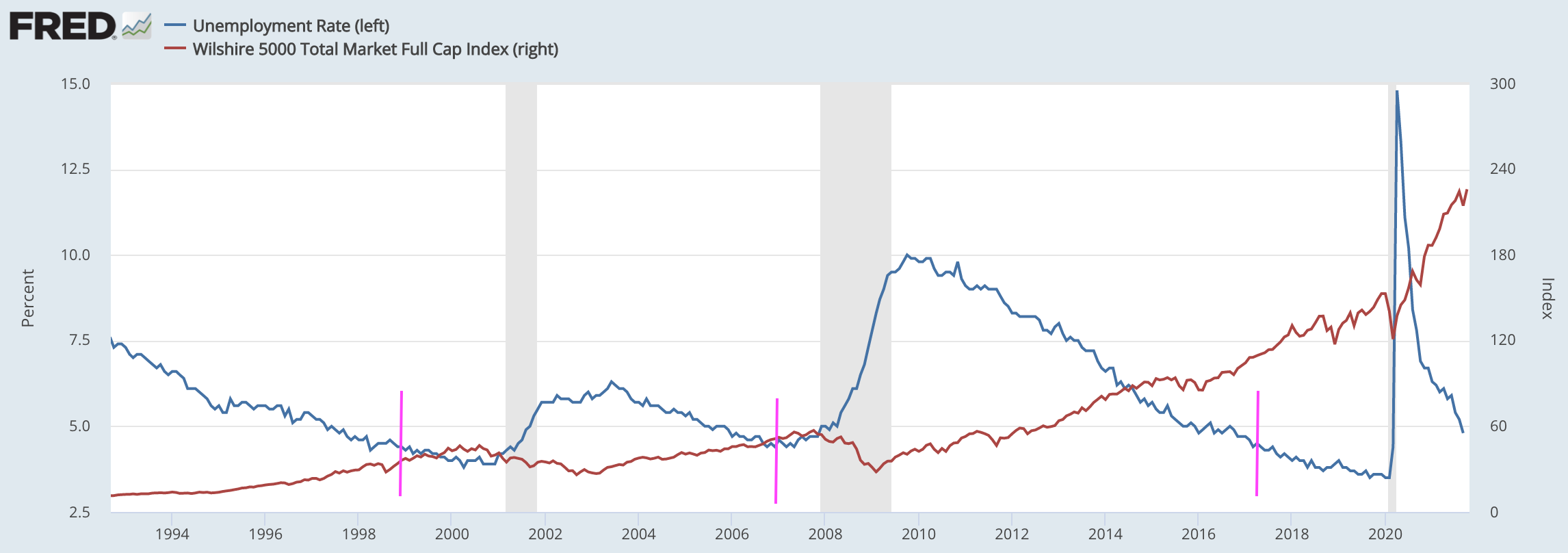

Plotting it on a graph: Labor market vs stocks

If we go back and look at previous business cycles in the US (which tend to be coordinated with those of other countries), every time the U-3 unemployment rate gets down to around 4 percent, the forward returns of stocks have been relatively low.

Each of the pink lines mark approximately the point at which U-3 unemployment went down to around 4 percent. This is a point at which policymakers increasingly become concerned about inflation.

Labor market vs. Stock market

(Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Wilshire Associates)

The Labor Market

The labor market follows the business cycle, so it’s a key factor for traders and investors looking at making tactical moves.

Over the long-run, productivity is the main factor that drives economic growth and asset price movements.

This is the process by which we learn more, do more, and invent more. Over time, more learning and information is gained than lost, so productivity generally increases over time and it’s not as volatile as credit and money cycles.

However, in the short-run, the cycles are more important.

The archetypical way stocks fall

When the labor market tightens to a point that produces excess price pressures in an economy, central bankers typically respond by raising interest rates, tapering asset purchases, and other ways of easing monetary stimulus.

Eventually they go too far because of how hard it is managing the late-cycle trade-offs between output and inflation, so there’s a drop in credit.

During the early stage of this credit crunch or liquidity crisis, there are typically the steepest drops in asset prices.

This catches many by surprise because they think the economy is strong and it’s confusing why it’s happening. (“The market’s being irrational.”)

During this phase, the money coming in to debtors via their incomes and new borrowing is not adequate to meet what they owe to their creditors.

Assets have to be sold to meet these obligations. Accordingly, expenditures are cut in order to stay liquid.

People eventually lose their jobs because there’s less economic activity. Aggregate incomes decline during this period. This causes spending to drop, in a self-reinforcing pattern.

Sometimes investors mistake the initial drop in asset prices as a buying opportunity. This is because they assume prices have fallen while earnings are still okay, giving assets better value.

But asset prices are being sold because of the realization (by some) that corporate earnings are about to fall.

When asset prices fall, this reduces the value of collateral and new borrowing. Less borrowing means less spending. One person’s spending is another person’s income, so incomes fall.

As such, the issue from asset prices falling is not only about wealth. By “wealth” it’s meant that financial assets are promises to pay money in the future.

But there is also the adverse feed-through effect into incomes.

Borrowers’ creditworthiness is measured as a function of:

- the net worths and credit ratios (value of assets, income, and collateral relative to their debts) and

- the sizes of their income in relation to the size of their debt service obligations

When borrowers’ net worths and incomes fall faster than their debts, they become less creditworthy.

Consequently, lenders are less inclined to lend.

This sets off a chain reaction which leads to less borrowing -> less income -> less spending -> lower asset prices -> lower collateral values -> less creditworthiness, and so on, which goes on in a self-perpetuating way.

Many borrowers end up being shut out from the credit markets entirely.

This is because the entities that can normally afford to lend are suffering losses on their assets and the forward economic landscape is highly uncertain during periods of substantial losses and high volatility in the financial markets.

New lending dries up and capital isn’t available.

This is often true even for companies that are run conservatively financially and for projects with high expected forward returns.

As the prices of risk assets, this causes risk-adjusted returns to rise.

Central bankers and other policymakers react to fix the situation when conditions become intolerable.

In developed markets today, interest rates are very low. So this presents a conundrum over how to ease when there’s that lack of flexibility to cut rates.

When nominal interest rates can’t be lowered much because they’re already at zero or slightly negative, this is where the government steps in as the lender of last resort and effectively has to reassure investors that they will come to the rescue and save the system.

The government – assuming they have a reserve currency and effectively have the power to do so – will guarantee that large amounts of money and credit will be made available to various entities in the economy so they can rely on a quick recovery.

However, this support from policymakers is usually not promised quickly enough. This means there are typically painful losses before this support is provided.

In most financial crises, there are also typically hang-ups and resentment toward certain actors who contributed to the crisis. Taxpayers don’t want their money used to support them and policymakers want them to have to bear the consequences of their choices.

Nonetheless, once it becomes evident that the cost of not providing support is greater than the cost of providing it, public officials inevitably come in to do what they can to support the whole.

Market participants can begin to see light at the end of the tunnel that capital markets will recover, as will lending activity and the overall economy.

Labor markets are generally weak to very weak at this point. But they improve once enough policy support is provided.

The speed at which they recover depends on the extent of the stimulus provided and the pace of the overall recovery of the credit and overall capital markets.

Labor market dynamics

Worker shortages can accelerate economic growth by prompting higher wages, new business formation and product development, and, over time, help increase labor supply as more workers enter the workforce due to the increased incentive for entrepreneurship and retraining.

If this happens in a fast enough manner it could mitigate the negative effects of labor scarcity on employment trends.

However, if it takes too long or is too slow workers may find themselves underskilled for the jobs they want because their previous skill sets aren’t employable in new roles unless they get retrained.

Those who experience unemployment or underemployment during this time may face negative consequences such as loss of skills or switching industries that will also affect future earnings power.

There are numerous examples. For example, in journalism, as it becomes increasingly digital, more workers in print and distribution will need to be retrained as those skills are less valued.

The labor market will face labor skill and labor availability issues.

An example of this was the labor scarcity that followed the 2008 recession. The US unemployment rate reached about 10 percent in October 2009. That same year, job postings on online job boards increased by about 40 percent as companies felt comfortable hiring again.

Employers began to seek candidates with more experience and higher qualifications for available jobs. Many employers were deepening their talent pools via recruitment strategies such as employee referral programs or enhanced outreach to social media communities where potential applicants represented much of the audience (e.g., LinkedIn).

On top of this, some companies outsourced some labor and had more flexibility due to technological changes like hiring digital workers remotely and freelancing platforms becoming popular and available during this time frame for technical labor.

As labor scarcity increased, labor prices (i.e., wages) began to rise as employers competed for limited labor supplies.

This left many job seekers with higher options and bargaining power than before the recession.

When labor is scarce

When labor is scarce, labor prices increase and companies are incentivized to invest in labor-saving technology such as equipment and software that can handle more jobs.

This will reduce labor costs but has a longer lead time.

For a shorter lead time, companies can offload labor to labor platforms or freelancers so labor costs can decrease without having to worry about whether the technology will be effective or efficient.

So while labor scarcity leads to increased labor costs, companies can adapt because of technological investments or hiring/retaining higher-skilled employees which require less hours and expenses for retraining and sustainment (i.e., education/training).

And as labor markets tighten it becomes more difficult for employers to fulfill customer demands because they don’t have enough employees for the necessary hours needed. The inability to meet demand leads businesses to restructure or reformat their business model via automation, increased overtime work, restructuring job responsibilities, and hiring employees who can cover multiple roles at once (e.g., full-stack developers).

Due to the cyclical nature of labor scarcities and labor shortages, these workers can expect to see their wages rise as they find employment and will tend to have less bargaining power when there’s lots of labor market slack.

Labor’s impact on margins

These labor dynamics are important not only for monetary policy, but also for company earnings and stock markets.

Labor costs are a significant portion of corporate balance sheets – about 55 percent of S&P 500 companies’ expenses.

This is typically three to four times other line items.

Since labor costs can be volatile and contribute significantly to operating margins, how well the business cash flows, and therefore stock market returns, it’s important to pay attention to labor dynamics and how they affect company earnings and stock prices.

For companies, labor costs vary at around +/−1 percent annually due to the business cycle and company-specific developments. During economic booms, there will be pressure to boost wages but also higher work productivity. During recessions, wage budgets are typically slashed but so is revenue.

So labor is a big deal for businesses – especially cyclical ones – and can be an important tool in assessing business health and stock market performance.

Labor share

Labor share is a concept that involves how income is split in an economy between workers and shareholders – basically what percent of total revenues goes to labor (i.e., salaries/wages).

If labor share falls, profits rise because labor costs fall.

The inverse also holds true. If labor share rises, then labor costs rise.

A decrease in labor share usually means that labor costs are decreasing as a percentage of the companies’ expenses which means labor scarcity is increasing, labor markets are tightening, companies are becoming more efficient with their workers, or automation is making labor cheaper through process re-engineering or technology while revenue stays consistent or increases.

In addition, labor share has been decreasing since the early 2000s. This is significant because labor scarcity should increase labor costs which means labor share should be coming back up – but it isn’t due to a variety of factors such as offshore outsourcing and technology replacing labor.

If labor share were to increase back up to historical averages (if labor continues down the same path) then this would mean labor prices will be under pressure, labor markets will tighten even more due to increased competition for employees (i.e., bidding wars if companies want these workers), business margins will decrease later in the business cycle when labor costs start making up a larger portion of total company operational expenses, and stock prices could experience downward pressure or muted returns because of increased labor costs.

Overall, most statistics show that labor shares are decreasing, labor markets are tightening, labor costs are on the rise, labor prices are under pressure (due to labor scarcity), and labor is becoming an increasingly larger portion of corporate operating expenses.

This is why labor dynamics are increasingly important to consider when investing or trading the business cycle – labor costs, labor scarcity, labor market tightness/efficiency, and labor share all provide important information on how cyclical labor markets can be as well as how labor’s contribution to company operational expenses will change over time.

Distributional impacts

In this environment, traders and investors will need to watch wage growth and inflation metrics.

They’ll also need to consider balancing tactical stock selections between capital-intensive and labor-intensive businesses.

Labor-intensive businesses include sectors like healthcare and consumer staples. Capital-intensive businesses include financials.

Conclusion

Labor market dynamics affect company earnings and stock markets directly via labor cost contributions to overall revenue and margins.

This makes it important for investors to understand how these can fluctuate from business cycle to business cycle depending on whether companies are hiring or firing en masse.

Labor scarcity will impact inflation, labor costs, labor availability, labor movements (labor reallocation), labor market structure (entrepreneurship and gig economy versus traditional companies), stock market performance, wage growth rate trends, monetary policy, and provide long-term structural shifts for employment.

Labor scarcity can put pressure on labor prices which are reflected in wages. When labor is scarce, the labor force has better bargaining power that results in higher wages. These conditions could lead to increased labor costs for employers and stock market returns may be lower for those who can’t adequately adjust.

As labor shortages occur, it may be good news for workers until businesses implement more automation and digitization in their business model(s) due to an insufficient amount of traditional labor.

The impact on stock market returns will depend on how quickly businesses adapt to these pressures while leveraging available artificial intelligence or other means of digitizing their business models before these methods themselves become obsolete due to technological advancement and competition from other players.