Why Does the US Dollar Rise in a Recession?

In a recession, the US dollar typically rises.

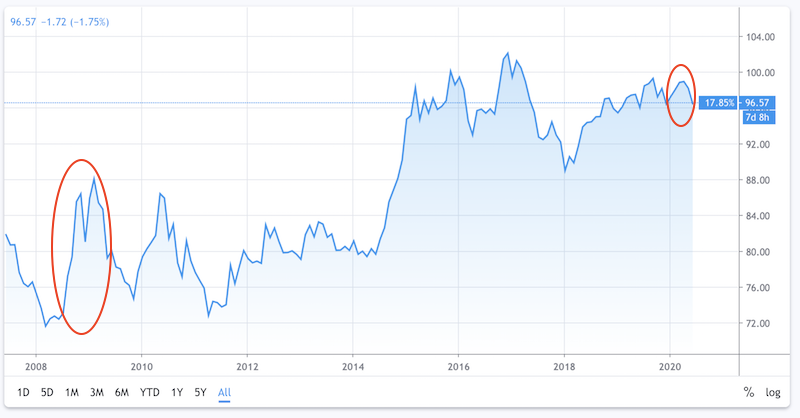

If we look at a chart of DXY (US dollar index), we can see a rise in 2008 due to the subprime crisis. The 2008 USD appreciation ended once the Fed eased in a material way. We’ve seen a bit of the same dynamic in 2020.

(Source: tradingview.com)

The short answer is that in times of reduced business activity, the root cause is lower trade activity. Lower trade activity, in turn, lowers the availability of dollars globally. This leads to a shortage relative to the demand, causing the price of the USD to increase. It is effectively a squeeze due to a lack of supply.

Even though the US is now only 20 percent of global economic activity, US dollars are 62 percent of foreign exchange reserves, 62 percent of international debt, 57 percent of global import invoicing, 43 percent of foreign exchange turnover, and 39 percent of global payments.

There’s a lot of debt denominated in dollars globally. When foreign countries don’t get those dollars coming to them when global trade slows, that raises the price due to the new dynamics of supply and demand.

The US trade deficit of some 2-2.5 percent of US GDP is a material source of liquidity to non-US entities. That deficit on its own pushes some $400-$500 billion of US dollars offshore into foreign hands each year.

Through an unprecedented money creation spree from the Federal Reserve and the opening up of FX swap lines, the USD has turned down. As the global economy recovers and trade picks back up, dollars circulate more and the supply constraints ease.

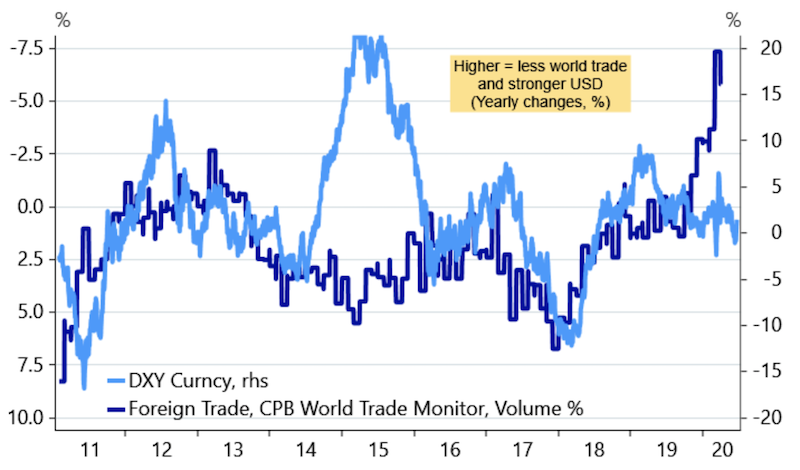

The chart below shows the inverse relationship between global trade flows (i.e., CPB World Trade Monitor) and DXY, the US dollar index benchmark. As world trade slows, the US dollar tends to appreciate.

When world trade slows USD gains and vice versa

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Moreover, many debt restructurings will need to occur. When companies default on their debt payments this reduces the need for currency and consequently reduces demand for it.

USD heading into H2’2020

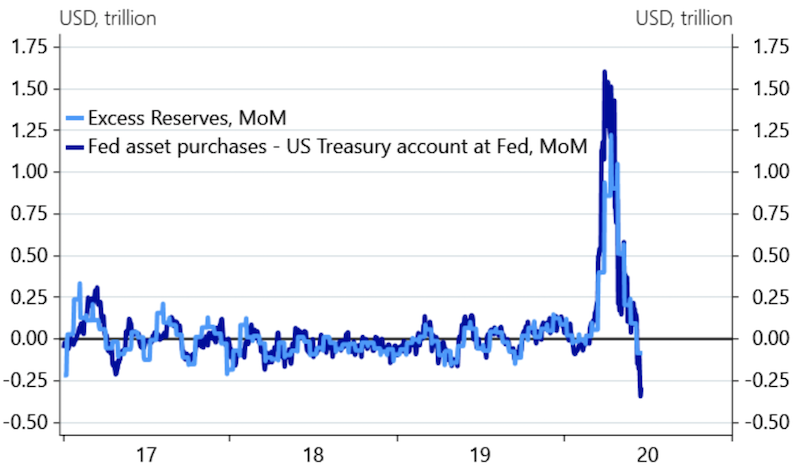

In terms of the near-term dynamics of the USD, the Treasury is currently issuing more debt than the Fed is purchasing. This is a net tightening of liquidity, which is bullish for the USD holding all else equal.

The Treasury’s balance at the Fed has taken more than $1 trillion out of the system that would have otherwise gone to commercial banks.

To weaken the USD, either the Treasury’s cash balance needs to come down or the Fed needs to buy more assets than what’s priced in.

Thinking long-term, the USD will need to come down relative to gold due to multi-hundred trillions in liabilities related to pensions, healthcare, other unfunded obligations (currently at around $300 trillion). That will all need to be monetized. That the Fed will be printing a lot more currency as time goes on is an understatement.

These liabilities could also technically be defaulted on, but that’s not politically popular to say the least and the US will always try to use the power of its own currency and the tools at its disposal to limit the burden (namely, keep interest rates low, change maturities of its debt, and devalue the currency to relieve the pinch of debt burdens).

USD liquidity has recently tightened as USD swaps are rolling off foreign central bank balance sheets. Moreover, this is being paired with a build-up of the Treasury’s cash buffer, removing USD from the system.

But if the US Treasury decides to bring down the Treasury General Account (currently at levels above $1,500 billion), this would help ease tightness in USD liquidity.

USD liquidity is shrinking quickly

(Source: Nordea, Macrobond)

Conclusion

Currently there are “cross currents” creating an equilibrium for the USD.

There’s the Fed’s zero interest rate policy and liquidity and credit support programs pushing more money and credit into the system. This is USD negative through increased supply. There will need to be a lot of “printing” going forward due to a combination of debt and debt-like liabilities that will require a combination of traditional and non-traditional monetary easing policies.

What needs to happen for the USD to depreciate in the short-term

It’ll be largely driven by three factors.

a) Fed buys up the excess debt issuance

b) Reduce debt issuance pace (which is the purview of the Treasury) or bring down the balance of the Treasury General Account to add liquidity into the system

c) A rebound in world trade, getting dollars to circulate in the places where they need to go