Risk Parity Strategy Without Bonds – How It Can Be Done

Risk parity is an investment strategy that aims to balance risk across asset classes, rather than allocating more capital to traditionally “safer” investments like bonds.

The goal is to create a portfolio with consistent returns, regardless of market conditions.

It’s also sometimes called balanced beta. It does not generally involve any tactical trading outside rebalancing to remain portfolio allocations.

The typical risk parity portfolio includes a mix of stocks, commodities, and other asset classes.

But what if you want to pursue a risk parity strategy without including bonds? Is it possible?

The short answer

The short answer is yes – it is possible to pursue a risk parity strategy without including bonds in your portfolio, or at least the type of bonds that offer bad returns relative to inflation and overall risk.

There are a few different ways to do this, which we’ll outline below.

Allocate to other asset classes

One way to go about pursuing a bond-free risk parity strategy is to simply allocate more capital to the other asset classes in your portfolio.

This means you would have a higher percentage of stocks and commodities, for example. Or other things that can serve as stores of value.

Focus on investments with high returns and lower volatility

Another way to pursue a bond-free risk parity strategy is to focus on investments that offer high returns and perhaps lower volatility.

This could include things like cash-flowing real estate or private equity, though both are still subject to the same economic forces as other forms of equity even if their returns aren’t marked to market. Risk simply doesn’t go away even when an asset is private and its price is “hidden”.

Ultimately, there is no one right way to pursue a bond-free risk parity strategy – it will depend on your specific goals and investment objectives.

But if you’re looking for ways to balance risk in your portfolio without including bonds, these are two options to consider.

And even if bonds are bad investments from a real returns perspective, some might even argue including some smaller amount of nominal rate bonds for their diversification value.

The problem with bonds today

Bonds are favored by many market participants because they’re generally safe:

- They have a fixed payout.

- They have a fixed maturity, making them less volatile.

- They’re senior to equity holders in the case of a company, so bondholders get paid first in the case something happens to the company.

But when looking at bond yields in your domestic currency, you have to look at your real yield; that is, your yield after adjusting for inflation.

If a bond yields 5 percent but inflation is 5 percent, you haven’t made anything in real terms – i.e., you haven’t gained purchasing power.

When looking at bond yields in foreign currency, what’s important is the yield relative to the movement in the exchange rate between the foreign currency and the one you make your payments in.

For example, if a bond yields 8 percent in a foreign currency, but that currency falls by 8 percent against your own currency, you made nothing in nominal terms.

Bonds have been mostly poor investments on a yield basis since the 2008 financial crisis – already a long time ago.

Though bond yields have crept up since 2020, inflation also increased and eroded the benefits of higher nominal yields.

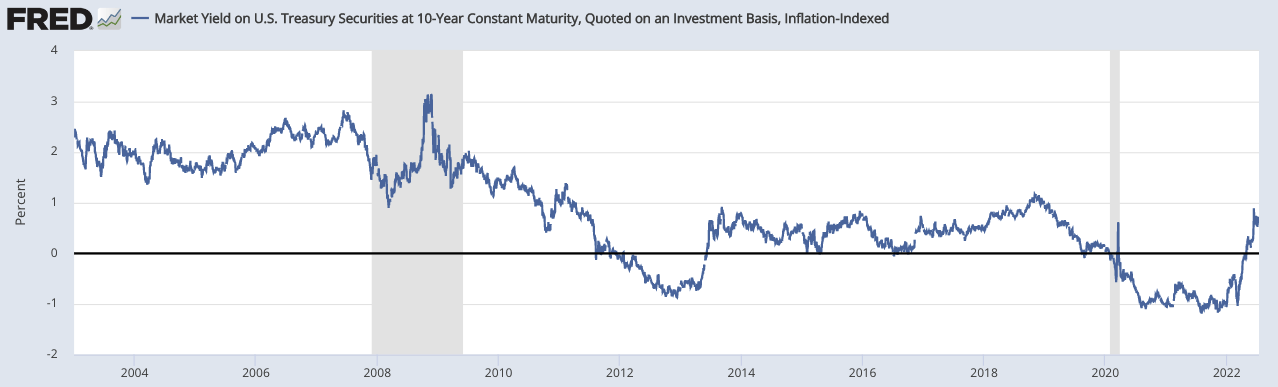

Below is a chart of the US 10-year yield on an inflation-adjusted basis.

Market Yield on US Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity, Quoted on an Investment Basis, Inflation-Indexed

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US))

Before getting 2-3 percent real returns on a 10-year bond was considered normal.

After 2008, anywhere from minus-1 to plus-1 percent has been the new norm.

With lower yields, means less return for each unit of volatility/risk.

This is pushing all kinds of private investors into other asset classes, not only those in risk parity.

How risk parity normally uses bonds

Stocks are about 3x as volatile as mid-duration government bonds.

This is because the cash flows of stocks are theoretically perpetual while those of bonds are fixed (the bond matures on a certain date).

And government bonds are backed by the government, which makes their cash flows generally more secure. In a reserve-currency country, they will always pay their bills in nominal terms.

But under approaches like a 60/40 portfolio, because stocks are more volatile than bonds, the risk ends up concentrated nearly 90 percent in stocks rather than the ostensible balance of weighting them by close to equal amounts of capital.

Risk parity aims to fix this by leveraging the fixed income side so that the risk of the bonds matches that of stocks and other assets in the portfolio.

This is normally done by borrowing cash to buy more bonds (easier to do when the yield curve is steep) or by using leverage-like techniques such as by buying futures to replicate higher bond exposure at a small collateral obligation. Or perhaps even through options.

But when the return on bonds weakens, the case for a higher allocation toward other assets grows.

Other asset classes outside bonds

Without nominal rate bonds you have other asset classes including:

Inflation-indexed bonds (ILBs)

Inflation-indexed bonds, also known as linkers or inflation-linked bonds, adjust the face value of the bond according to changes in a consumer price index (CPI).

It’s important to note that inflation-linked bonds carry interest rate risk just like nominal rate bonds.

They are not pure inflation investments that simply give you the price level.

For those looking for more of a pure investment – i.e., does well when inflation rises faster than discounted expectations – they would be looking at an inflation swap or CPI swap.

This is a type of OTC derivative available to institutional investors.

For those who don’t have access to inflation or CPI swaps, one can go long an ILB and short the equivalent tenor nominal rate bond.

For example, one might go long a 10-year TIPS bond and short a 10-year US Treasury nominal rate bond.

If discounted inflation expectations rise, the trader or investor would benefit similar to an inflation swap.

Equities

Equities (stocks) are one of the most common asset classes.

There are different types of stocks, including:

- Growth stocks: Companies that are expected to grow at a faster rate than the markets they compete in

- Value stocks: Companies that may be undervalued by the market and offer potential for capital appreciation

- Dividend stocks: Companies that pay out regular dividends to shareholders

Commodities

Commodities are natural resources that can be bought and sold.

They include things like precious metals (gold, silver, platinum), energy (oil, gas, coal), agricultural products (wheat, corn, soybeans), and base metals (copper, zinc, iron ore).

Commodities have low correlations with both stocks and bonds because they tend to do well in an inflationary environment (and can even be the cause of inflation itself to a partial or full degree), so they can act as a good diversifier.

And because commodities are priced in dollars (or other currencies), their prices tend to go up when the dollar falls.

This provides some protection against currency debasement, which is often a byproduct of inflation.

So, in some ways, inflation can be thought of as alternative currencies, assets with real value, and follow the “inverse money” concept in that their values are partially attributed to the value of the money used to buy them.

Real estate

Real estate is another asset class that can offer high returns and low volatility.

There are different types of real estate investments, including:

- Residential real estate: This could include things like single-family homes, condominiums, and apartments.

- Commercial real estate: This could include office buildings, retail space, warehouses, and storage units.

- Industrial real estate: This could include factories, manufacturing plants, and distribution centers.

Private equity and private businesses

Private equity is a type of investment that’s not traded on public markets.

It typically involves investing in companies that are not publicly traded, or that are going through a major transition such as a merger or acquisition.

Private equity can offer high returns, but can also be a higher-risk investment, depending on the exact nature of what’s being done.

Private businesses are another type of investment that can offer high returns.

These are businesses that are not publicly traded, and they can include anything from small businesses to large companies.

Investing in private businesses can be a risky investment, but it can also offer the potential for high returns.

When it comes to institutional private equity, there are two types of funds: buyout and growth.

With a buyout fund, the focus is on acquiring a controlling interest in a company and then improving its operations to increase the value of the business.

With a growth fund, the focus is on investing in companies that are expected to experience high levels of growth.

Growth funds can be more risky than buyout funds, but they also have the potential for higher returns.

And growth is also closer on the spectrum toward venture capital.

Most small business opportunities provide the opportunity for higher returns than traditional investments in the stock market.

Other bonds that are “good”

If there are bonds that are yielding less than (or well less than) the rate of inflation, you can avoid those by looking for better ones.

These can include:

- Inflation-linked bonds (aforementioned)

- Foreign currency bonds (they can also provide some level of diversification)

- Corporate bonds

That way you can have access to different countries and different currencies (an important part of the overall diversification process) without having to put all your bond allocation in a certain country (e.g., US) or from a certain issuer (e.g., federal government).

You can also look at different maturities, since bonds with longer terms will generally have higher yields than bonds with shorter terms.

However, you need to be careful with long-term bonds, because if interest rates rise you could end up losing money on your investment on a mark-to-market basis.

Moreover, with corporate bonds, you have to keep a keen eye on risk. Bonds with high yields often price a higher-than-comfortable risk of bankruptcy.

Example of a risk parity portfolio without bonds (or bonds that aren’t terrible)

Above, we established that the main problem with bonds is their low yields relative to inflation in most countries.

This is especially true in reserve-currency countries, such as bonds denominated in dollars, euros, yen, and other reserve currencies.

Inflation-indexed bonds, foreign bonds, and higher-yielding corporate bonds can be a part of your portfolio.

If you go too heavily in any asset class, your portfolio will have a tendency to behave well in certain environments and poorly in others.

For example, many retirees are afraid of owning stocks because they don’t want the volatility.

But if they concentrate too heavily in cash and safer bonds, their portfolio will also have environmental bias.

Their portfolio might suffer when growth is above expectation and inflation runs higher. They could compensate for this risk by buying something different from what they already have (such as stocks or commodities) to help offset it.

Here is an example portfolio:

Portfolio Allocations

| Asset Class | Allocation |

|---|---|

| US Stock Market | 25.00% |

| Gold | 12.00% |

| Commodities | 8.00% |

| TIPS | 35.00% |

| Long-Term Corporate Bonds | 10.00% |

| Total US Bond Market | 5.00% |

| Global Bonds (Unhedged) | 5.00% |

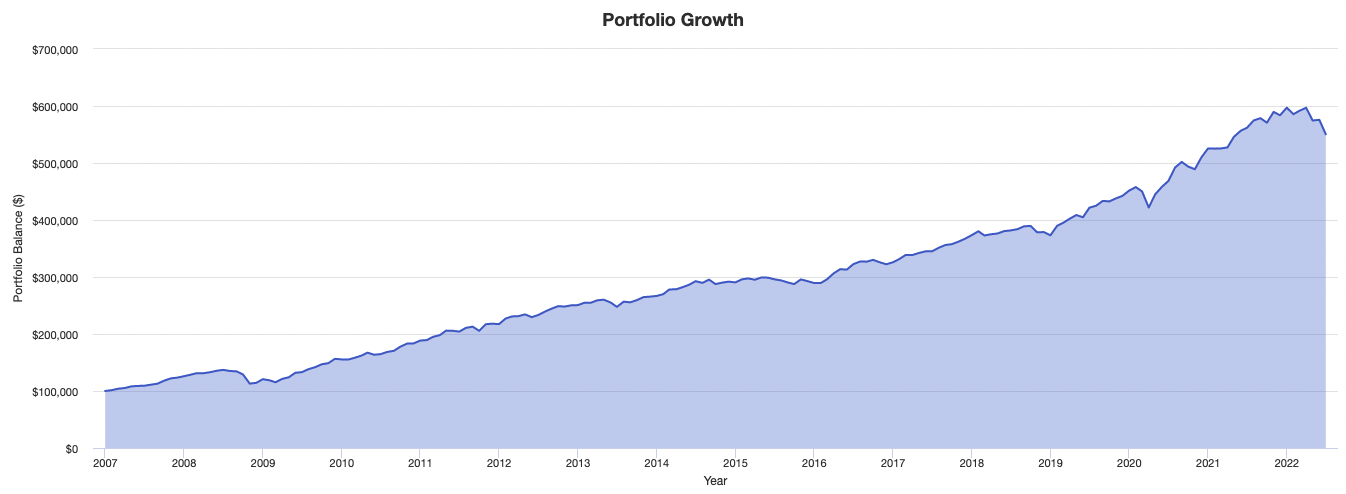

The portfolio returns below assume a starting amount of $100,000 and fixed $1,000 contributions per month, with those contributions inflation-adjusted.

The compounded annual gross returns (CAGR) reflect this below.

The time-weighted rate of return (TWRR) is another measure of the compound rate of growth in a portfolio. The TWRR helps eliminates the effects on growth rates created by inflows and outflows of money that would distort standard return numbers.

The money-weighted rate of return (MWRR) refers to the discount rate that equates a project’s present value cash flows to its initial investment. The MWRR is also sometimes called the internal rate of return (IRR).

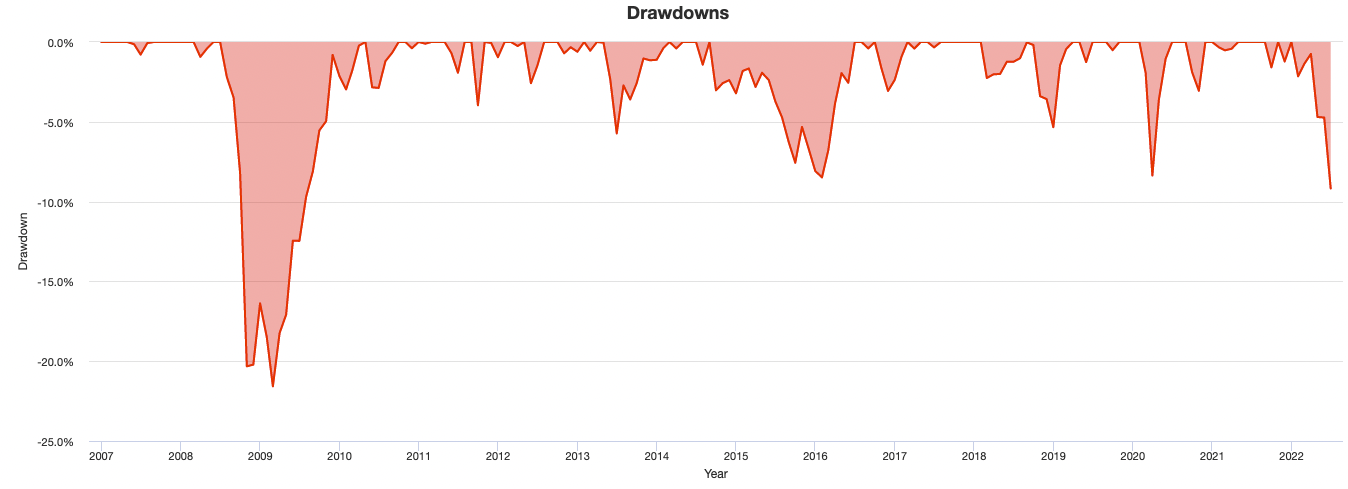

These portfolio returns are from 2007 forward, given the data for the commodities asset class only went back to that year.

Portfolio Returns

| Portfolio | Initial Balance | Final Balance | CAGR | TWRR | MWRR | Stdev | Best Year | Worst Year | Max. Drawdown | Sharpe Ratio | Sortino Ratio | Market Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portfolio 1 | $100,000 | $550,412 | 11.63% | 5.37% | 5.28% | 7.68% | 17.05% | -13.27% | -21.57% (-17.55%) |

0.62 | 0.88 | 0.77 |

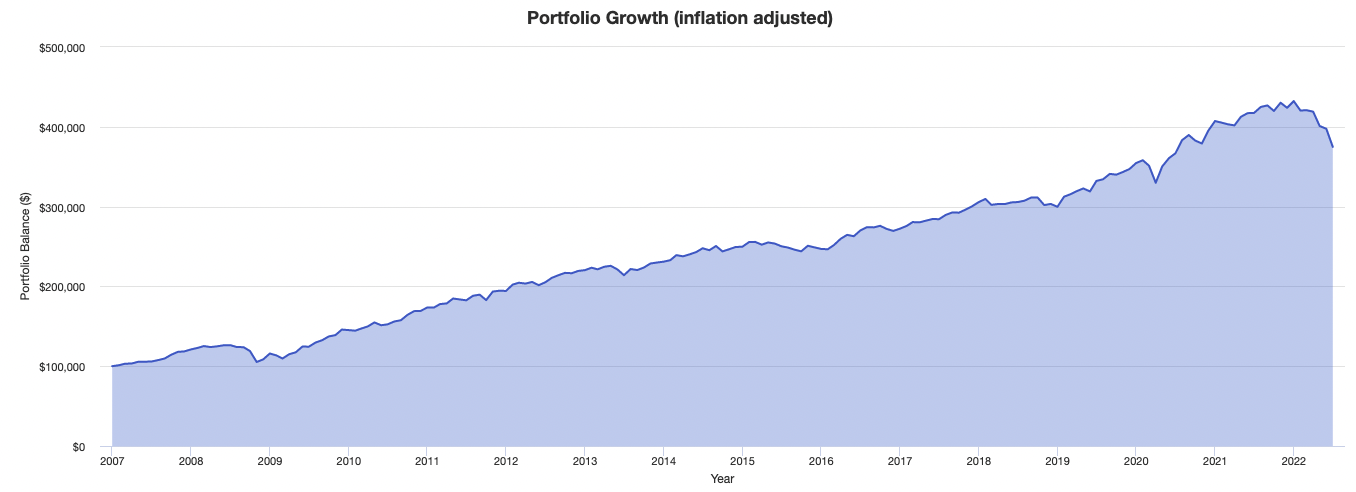

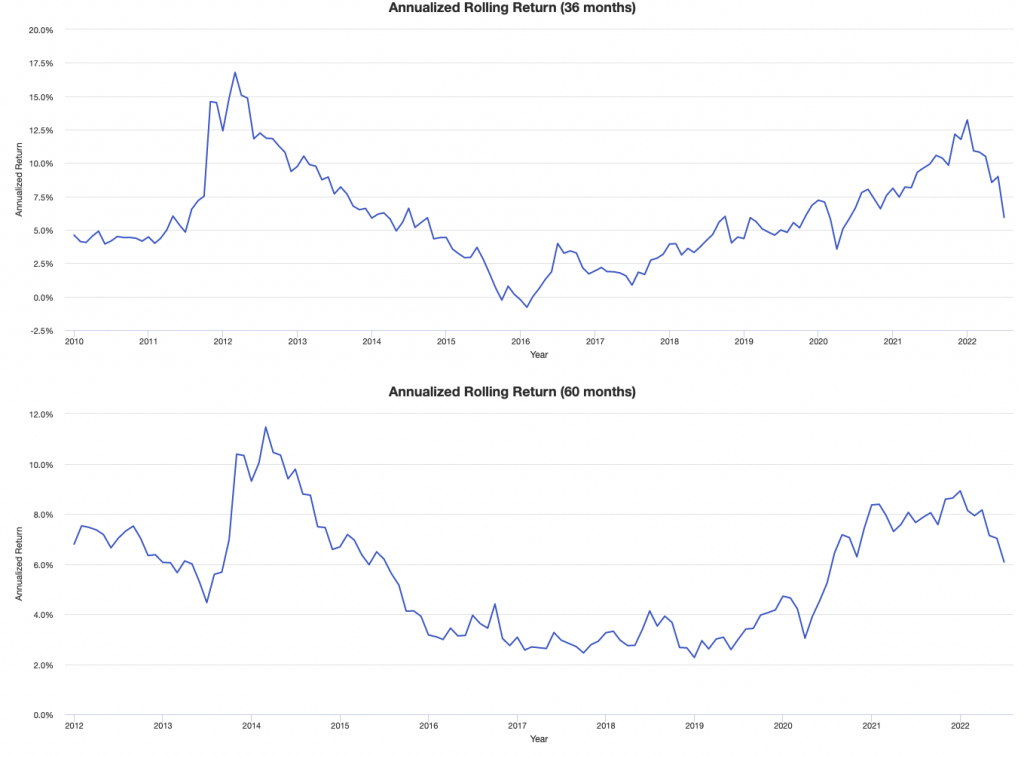

The charts below show portfolio returns in both nominal (top) and real (bottom) terms:

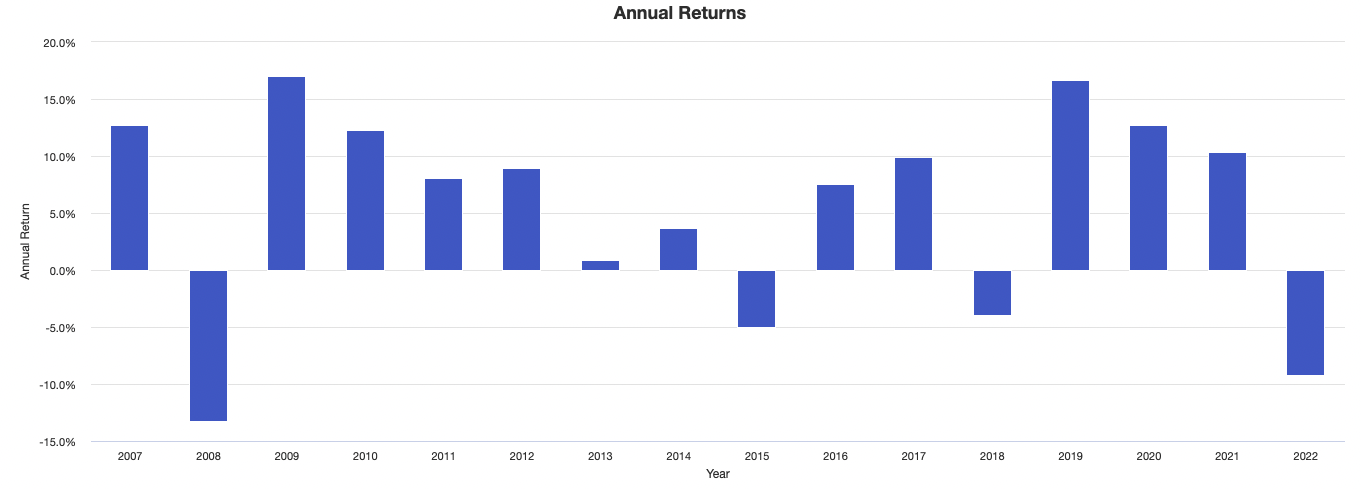

Annual returns by year:

More statistics and charts about this portfolio are included in the appendix at the bottom of this article.

Risk Parity Strategy Without Bonds – FAQs

What is risk parity?

Risk parity is an investing strategy that aims to balance risk across different asset classes.

The goal of risk parity is to create a portfolio that has the same level of risk regardless of which asset class is performing well or poorly.

What are the benefits of risk parity?

Risk parity can provide diversification benefits and the potential for higher returns.

When done correctly, risk parity can help investors achieve their goals while taking on less risk.

What are the challenges of risk parity?

Risk parity can be difficult to implement and maintain. It also requires a willingness to take on more risk.

How can I do risk parity without bonds?

It’s possible to do risk parity without bonds, but it will require a different asset allocation mix.

Instead of using bonds to provide stability and offset risk, you’ll need to use other asset classes like equities, commodities, real estate, private equity, and private businesses.

Each of these asset classes has different risks and rewards, so it’s important to carefully consider your investment objectives before allocating assets to your portfolio.

What is a risk parity fund?

A risk parity fund is a type of investment fund that aims to achieve risk parity across different asset classes.

Risk parity funds typically hold a mix of assets, including stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate.

What is the difference between risk parity and traditional portfolio construction?

Traditional portfolio construction relies on historical data to predict how different asset classes will perform in the future.

This approach can often result in portfolios that are overweight in certain asset classes that may be due for a correction.

Risk parity, on the other hand, relies on concepts of modern portfolio theory to construct portfolios that are designed to have the same level of risk regardless of which asset class is performing well or poorly.

What is an example of a risk parity portfolio?

A risk parity portfolio might hold a mix of stocks, bonds, commodities, real estate, private equity, and private businesses.

The exact mix will depend on the investment objectives of the individual investor.

What is the difference between risk parity and balanced investing?

Balanced investing is an investing strategy that aims to achieve a balance between different asset classes.

Risk parity is similar to balanced investing, but it goes one step further by aiming to achieve a balance of risk across different asset classes.

There are different concepts within the balanced approach, such as barbell investing and various simplification strategies.

Is risk parity a good investment strategy?

There is no easy answer when it comes to whether or not risk parity is a good investment strategy. Ultimately, it depends on the individual investor’s goals and risk tolerance.

If you’re interested in pursuing a risk parity strategy, it’s important to work with a financial advisor to make sure it’s the right fit for you.

Conclusion – Risk Parity Strategy Without Bonds

Risk parity is a strategy that involves investing in a variety of asset classes in order to balance risk and return.

This can be done with or without bonds, but it’s important to understand the risks and potential rewards associated with each option before making any decisions.

It will require a different asset allocation mix.

Instead of using bonds to provide stability and offset risk, you’ll need to use other asset classes like equities, commodities, real estate, private equity, and private businesses.

Each of these asset classes has different risks and rewards, so it’s important to carefully consider your investment objectives before allocating your portfolio.

But if you’re willing to take on a bit more risk, investing in a mix of these asset classes could offer the potential for higher returns.

If you’re looking for high returns, investing in private businesses can be a good option where there is less competition or you can take advantage of a specific skill set you may have.

But even if you’re considering the benefits of having a balanced portfolio, you might want to consider a portfolio that includes some bonds in various forms, even if they have low yields due to their ability to diversify the portfolio.

Appendix

Monthly Correlations

| US Stock Market | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.77 |

| Gold | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.58 |

| Commodities | 0.51 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.18 | -0.03 | -0.15 | 0.39 | 0.61 |

| TIPS | 0.23 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| Long-Term Corporate Bonds | 0.24 | 0.35 | -0.03 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.57 |

| Total US Bond Market | 0.08 | 0.42 | -0.15 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.48 |

| Global Bonds (Unhedged) | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.84 |

Portfolio Assets

| US Stock Market | 8.52% | 16.10% | 33.35% | -37.04% | -50.89% | 0.54 | 0.78 | 1.00 |

| Gold | 6.53% | 17.25% | 30.45% | -28.33% | -42.91% | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.07 |

| Commodities | -3.49% | 23.97% | 38.77% | -45.75% | -88.68% | -0.06 | -0.07 | 0.51 |

| TIPS | 3.68% | 5.61% | 13.23% | -8.92% | -12.50% | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.23 |

| Long-Term Corporate Bonds | 5.21% | 10.01% | 20.41% | -21.48% | -24.53% | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.24 |

| Total US Bond Market | 3.08% | 3.63% | 8.61% | -10.46% | -12.32% | 0.63 | 1.00 | 0.08 |

| Global Bonds (Unhedged) | 2.53% | 7.15% | 22.75% | -14.98% | -19.17% | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.55 |

Rolling period returns

| Roll Period | Average | High | Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 6.21% | 25.21% | -20.74% |

| 3 years | 6.00% | 16.78% | -0.79% |

| 5 years | 5.57% | 11.46% | 2.27% |

| 7 years | 5.11% | 7.52% | 2.59% |

| 10 years | 5.40% | 6.95% | 4.29% |

| 15 years | 5.84% | 6.23% | 5.34% |

Portfolion statistics

| Arithmetic Mean (monthly) | 0.46% |

|---|---|

| Arithmetic Mean (annualized) | 5.68% |

| Geometric Mean (monthly) | 0.44% |

| Geometric Mean (annualized) | 5.37% |

| Standard Deviation (monthly) | 2.22% |

| Standard Deviation (annualized) | 7.68% |

| Downside Deviation (monthly) | 1.52% |

| Maximum Drawdown | -21.57% |

| Stock Market Correlation | 0.77 |

| Beta(*) | 0.37 |

| Alpha (annualized) | 2.06% |

| R2 | 58.95% |

| Sharpe Ratio | 0.62 |

| Sortino Ratio | 0.88 |

| Treynor Ratio (%) | 12.93 |

| Calmar Ratio | 0.65 |

| Active Return | -3.15% |

| Tracking Error | 11.33% |

| Information Ratio | -0.28 |

| Skewness | -1.39 |

| Excess Kurtosis | 7.49 |

| Historical Value-at-Risk (5%) | -2.98% |

| Analytical Value-at-Risk (5%) | -3.18% |

| Conditional Value-at-Risk (5%) | -5.08% |

| Upside Capture Ratio (%) | 36.40 |

| Downside Capture Ratio (%) | 29.90 |

| Safe Withdrawal Rate | 8.68% |

| Perpetual Withdrawal Rate | 2.80% |

| Positive Periods | 116 out of 186 (62.37%) |

| Gain/Loss Ratio | 1.08 |

| * US stock market is used as the benchmark for calculations. Value-at-risk metrics are based on monthly values. | |