Why You Should Focus on Real Returns, not Nominal Returns

Over time, real returns (i.e., inflation-adjusted returns) are what matter for your portfolio, not nominal returns.

The wealth that we have is not how much money we have. It’s the buying power of that money.

For example, if the inflation rate is 5 percent and an asset you hold simply stayed steady all things considered, then in nominal returns you didn’t lose anything, even though the buying power of that asset fell by 5 percent.

The entire purpose of why we trade and invest is to convert it into buying power down the line.

Central bankers are going to always target an inflation rate of at least zero to avoid deflation, so holding an asset mix that at least matches this rate of inflation is crucial to at least maintain your buying power.

If you are not at least maintaining your buying power, then you are essentially going backward.

Example

Using real estate as an example, let’s say someone owned a 2-bedroom apartment in NYC.

They might get around $5,500 per month in rent but their all-in costs might be around $7,500 per month. So they run it cash flow negative and need real appreciation just to break even.

In other words, the appreciation that they require – just for the investment to hold its real value – would be a rate equal to:

- the sum required to fill in the nominal loss, plus

- the inflation rate

So, if inflation were 8 or 9 percent, for instance, anything below a low double-digit nominal return they would be losing on it.

Even if the property increased in value by exactly the $2,000 per month to effectively cover the negative cash flow, the inflation rate would erode its buying power.

And for someone using that as their primary home, they don’t get that $5,500 per month in rent to help cover the carry and expenses. So accordingly, their hurdle rate is even higher than somebody who’s a landlord.

Inflation not only squeezes spenders, but squeezes investors as well whose returns (in most cases) begin to lag the rate at which prices go up.

Price stability is always the bedrock of an economy.

How do central banks get inflation down?

There’s of course the obvious answer – they use their policy tools, such as raising interest rates and selling securities off their balance sheet (if applicable) in a process known as quantitative tightening (QT) or reverse quantitative easing (reverse QE).

How this is done from country to country varies.

But the nature of what’s defined as inflation matters as well.

Monetary policy in the US operates so heavily through housing because over 40 percent of what makes up inflation is now in that category (which they call “rents”).

So if the Federal Reserve wants to kill off inflation (i.e., back to about a zero percent level), they need to at least kill off housing growth in nominal terms.

Getting housing to a 0 percent nominal growth rate on aggregate (which would put it negative in real terms because other parts of the CPI inflation gauge would be positive) would be about ideal.

A heavy dose of shedding mortgage-backed securities (MBS) from their portfolio to engineer mortgage rates higher will do the trick and that’s what they’re doing.

What if inflation doesn’t fall?

If inflation stayed at nine percent, for example, people in an asset mix that only maintained its value in nominal terms would lose about 40 percent of their wealth in 5 years.

That’s why only tracking nominal values in anything – salary, home value, cash, stocks – isn’t very useful.

For instance, if someone has an income of $100k per year, if inflation stayed at nine percent for 5 years, they would need an income of $154k by that point just to maintain their purchasing power.

Is inflation a necessary evil?

It’s a big part of how governments can satisfy their obligations when they can’t tax people more.

They either get the money in hard form (taxes and other forms of revenue) or soft form (printing money).

When they can’t get enough hard currency flow, they get it through “printing” money (i.e., electronic money creation).

They create a lot of fixed-rate assets that barely yield anything (cash and fixed-rate credit) and return a negative real interest rate on them – i.e., the rate they pay on it doesn’t compensate for rises in the price level – so they can get their money via the trade-off of eroding people’s buying power instead.

For example, if inflation is 9 percent and someone has $1 million in a bank account that yields 0-1 percent interest, it’s like having an extra tax bill of $80k a year based on the rate at which it’s being devalued.

Classically, the best time to buy risk assets is when the economy is weak and there’s lots of capacity (low growth rate, low inflation, high unemployment).

Conversely, the worst time to buy risk assets is when there is a high nominal growth rate, high inflation, and low unemployment.

To get inflation down in such an environment, they (the Federal Reserve and other central banks facing this problem) need to inflict losses on asset holders.

It’s through a negative wealth effect from falling asset prices and higher unemployment that they can engineer lower spending.

It also, unfortunately, means a lot of people will end up losing their jobs and the labor markets are still strong during the initial stages of the tightening.

Tightening of financial conditions always cuts credit first, then spending, and income (i.e., labor) falls last. Unemployment normally peaks early in the next expansion not within the recession itself.

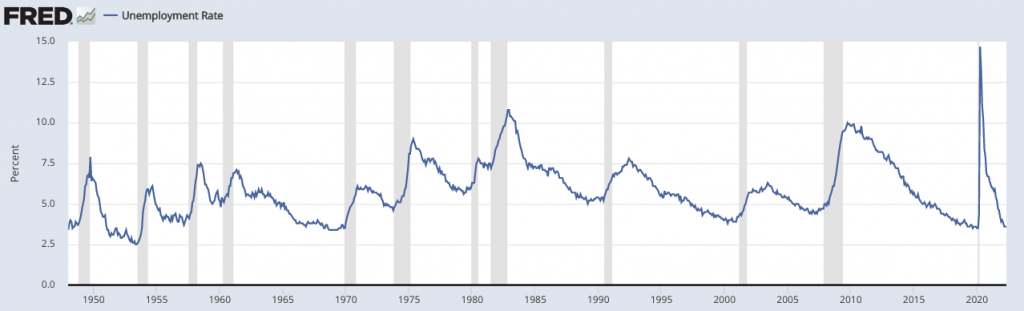

You can see this phenomenon in the graph below:

Unemployment Rate

(Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

When people lose their jobs, they don’t have money coming in, so this also triggers further asset sales so they can raise cash. This in turn reduces their prices further.

Policymakers can’t let the inflation issue persist, so that’s the trade-off.

Longer-term, with:

- more than $30 trillion in federal debt, and

- over $200 trillion in off-balance sheet liabilities (e.g., $22 trillion in Social Security, $34 trillion Medicare, $170 trillion in other unfunded liabilities)

- against just $4.4 trillion in annual federal tax take, and

- $6.1 trillion in annual spending…

…they’ll continue to pay their bills by issuing debt then monetizing it with “printed” money, which will materially devalue dollar cash and credit. (It’s a similar situation in other developed markets.)

What can central bankers do about inflation that has a hefty supply component?

Central banks control demand but they can’t directly do much about supply.

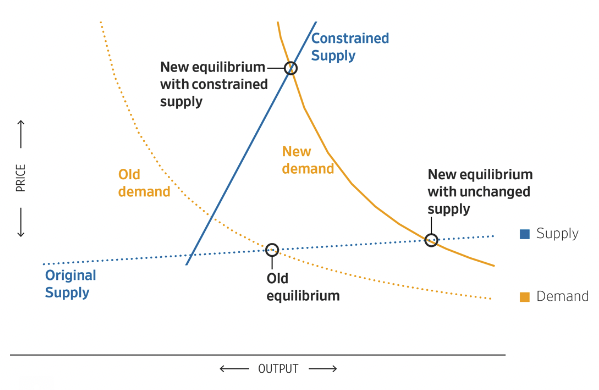

Normally, supply is quite elastic. In economics, the supply curve of most goods and services is relatively flat, as shown by the dotted blue line in the chart below.

(Source: WSJ)

Higher demand, which is shown by a rightward shift in the demand curve – mostly leads to a response of higher output, and only slightly higher prices.

For example, after the Fed cut rates in the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, light vehicle sales went up 15 percent while prices rose only 1 percent.

But since early 2021, disruptions associated with supply chains have made the supply curve much more vertical in many sectors: Higher demand has increased prices much more than output. In other words, supply has become more inelastic.

First-quarter auto sales in 2022 were down 17 percent from late 2019 while prices were 15 percent higher.

The good news is that a big drop in demand in these circumstances might therefore reduce inflation without much hit to output.

What if no asset returns more than the rate of inflation? What if I think asset prices will fall?

If you think stuff is going down, then you can short it. Or you can construct relative value trades where you short one thing and go long another to take advantage of the divergence that’s likely to take place.

In an inflationary environment, at a broad level, this tends to be bad for bonds and bad for stocks, and good for commodities (sometimes commodities are the cause of part of the inflation problem).

But that doesn’t mean that all stocks or all bonds are bad.

Within the stock market, you can consider companies that sell the stuff that benefits from the high levels of nominal spending and have clean balance sheets such that they aren’t hit much by the rises in interest rates.

Consumer staples and utility companies, for example, may do well in this environment or at least outperform other sectors.

Humans always need food, water, electricity, and all the basics. So that stuff is always going to get bought no matter how the economy is doing.

You can also consider shorting the stuff that people don’t need, and especially companies that don’t make any money or very little money and are highly indebted.

Within the bond market, you can consider inflation-linked bonds and short fixed-rate bonds whose yields don’t adequately compensate for the inflation rate and credit risk.

That’s basically the playbook until they kill inflation or until the drop in output is a worse issue than the inflation problem and policy pivots back from tightening to easing again.

In markets, it’s all about how things transpire relative to what’s discounted in.

If you think the discounted inflation rate is too low and the discounted growth rate is too high, the goal would be to hold a mix of long and short positions that set up well for a low-growth and high-inflation environment.

When markets fall, most people do poorly because they’re biased to be long everything. If you don’t have directional biases, you can just focus on making the best decisions and benefiting from the price falls (or gains) that need to take place.

But doing all this tactical work is not easy to pull off.

For example, for the first six months of 2022, being short Italian sovereign debt (BTPs) was a good trade because the yield on their bonds was far too low relative to their inflation rate and sovereign credit risk, and many would want to be short the euro (the currency those bonds are denominated in) as the EU was about to head into recession ahead of the US.

Price chart of Italian BTPs

But the European Central Bank (ECB) determined that the price falls were widening Italy’s credit spreads to a level they weren’t comfortable with. Itcould create fragmentation risk in the EU; in other words, risk breaking up the currency union.

So they decided to start buying Italian debt since private market participants didn’t want it. It was a good trade until it wasn’t.

You can have a great idea, then have it go against you for reasons outside the original thesis.

By and large, trading is not easy. Most individuals are probably best served to focus on saving what they can and having a well-diversified portfolio that doesn’t have environmental bias so it can do well no matter what the state of the world is.

This means diversification by:

- different assets

- different asset classes

- different countries

- different currencies

- different financial and nonfinancial stores of value

This way you won’t have the big ups and downs associated with being too concentrated in any one thing.

Capital shifts and moves around far more than it’s destroyed. When stocks fall, that doesn’t necessarily mean the money disappeared (net wealth/credit destruction). Most or all of it likely simply went somewhere else.

So if you have good strategic balance you will extract risk premiums in a relatively efficient way, rather than having the risk associated with high levels of concentration.

Eighty percent of the world’s output is outside the United States. Ninety-six percent of the world’s population is outside the US, so most of that 80 percent will continue to grow as the rest of the world makes productivity gains versus the US.

So when thinking about the global income stack holistically, there’s a lot of opportunity outside the US with higher growth rates.

Some markets you may not be able to access or may not want to access due to capital controls, political instability, and so on, but there is lots of opportunity in other markets.

Moreover, policymakers are not as constrained in many other markets as they are in the US, developed Europe, and Japan, the three main reserve currency regions of the world.

Real returns vs. Nominal returns – FAQs

What’s the difference between real returns and nominal returns?

Real return is the actual return you experience after accounting for inflation.

Nominal return is the “headline” or advertised return, which doesn’t account for inflation.

Why does it matter whether I focus on real or nominal returns?

It can matter a lot.

For example, if you’re saving for retirement, you need to think about how much purchasing power you’ll really have in retirement.

If you’re focused on nominal returns, you might end up with less purchasing power than you expect because inflation will erode your real returns.

How can I calculate my real return?

The most basic way is to subtract the inflation rate from your nominal return.

For example, if you have a portfolio that earned a 10 percent nominal return last year and inflation was 2 percent, your real return would be 8 percent.

What’s the difference between inflation and deflation?

Inflation is when prices rise and purchasing power falls.

Deflation is the opposite – when prices fall and purchasing power increases.

Deflation is rare because central bankers try to maintain at least a zero percent inflation rate to help maximize output and push along resource allocation to minimize slack.

What causes inflation/deflation?

There are a lot of different factors that can cause inflation or deflation, but one of the most important is the money supply.

If there’s more money chasing the same amount of goods, prices will go up (inflation). If there’s less money chasing the same amount of goods, prices will go down (deflation).

What’s the difference between an asset’s price and its value?

An asset’s price is what you pay for it today.

Its value is what it’s really worth – its intrinsic or underlying value.

How can an asset’s price and value be different?

There are a lot of reasons why an asset’s price might not reflect its true value.

One reason is that people’s perceptions can change, which can cause prices to go up or down even if the underlying value of the asset hasn’t changed.

Another reason is that prices can be affected by things like supply and demand, taxes, and fees.

For example, if there’s high demand for an asset but limited supply, the price will go up even if the underlying value stays the same.

What’s the difference between an asset’s price and its return?

An asset’s price is what you pay for it today. Its return is the money you make (or lose) on it over time.

How can an asset’s price and return be different?

The same factors that can cause an asset’s price to be different from its value can also cause its return to be different from its price.

In addition, returns can be affected by things like dividends, interest payments, and capital gains or losses.

What’s the difference between absolute returns and relative returns?

Absolute returns are the actual gains or losses you experience on an investment. Relative returns are how your investment performs compared to other investments.

For example, if you invest in a stock that goes up 10 percent, your absolute return would be 10 percent. But if the market as a whole goes up 20 percent, your relative return would be minus-10 percent (because you didn’t make as much money as the market did).

What’s the difference between risk and volatility?

Risk is the chance that you will lose money on an investment. Volatility is how much an investment’s price moves, or expects to move (i.e., implied volatility), up or down.

Investments with high risk usually have high volatility, but this isn’t always the case.

For example, a bond might have low risk but high volatility if interest rates go up.

What’s the difference between a short-term investment and a long-term investment?

A short-term investment is an investment that you expect to hold for one year or less. A long-term investment is an investment that you expect to hold for more than one year.

The time horizon of your investment can affect how risky it is. In general, the longer you’re willing to wait, the more risk you can take on.

It also has implications for tax purposes, as capital gains taxes are often structured with a one-year time threshold in terms of what’s considered a short-term or long-term capital gain.

What’s the difference between an active investor and a passive investor?

An active investor is somebody who tries to beat the market by picking stocks, securities, or other instruments, timing his or her investments, and/or using other strategies.

A passive investor is somebody who invests in a way that tracks the market, such as through index funds.

Passive investing is generally less risky than active investing, as active investing can rack up transaction costs, fees, and is subject to potential underperformance due to tactical trading.

Conclusion

To recap, you should focus on real returns rather than nominal returns when thinking about your investment portfolio.

Real returns take inflation into account, while nominal returns do not.

Your wealth is not how much money you have; it’s your spending power. So, if you want to know how well your investments are really doing, focus on real returns.

So, above all, it’s best to monitor the real returns of your portfolio and not only the nominal price swings.

This also goes for other things – your salary, your home value, your cash savings, and your liabilities as well, such as your mortgage and loans.