4 Reflation Trades & Their Counterarguments

After a recession, the central bank has big incentives to get the economy going again. Traders then largely shift to what are called reflation trades, which will benefit from this backdrop.

Central banks start by lowering interest rates. This makes cash less attractive to own. This incentivizes the ownership of riskier assets and more spending in the economy, which increases corporate earnings.

If necessary, they’ll lower long-term interest rates through the buying of bonds and other long-duration assets (potentially ETFs and stocks as well), sometimes known as QE.

If even further stimulus is needed, there will be a coordination of monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Those are the basics.

What reflation trades are the most popular?

There are four main reflation trades or themes when governments are providing large-scale policy aid to an economy.

We’ll go through them individually.

Short bonds

Cash and nominal rate bonds are bad investments in a typical reflationary environment because governments are “printing” a lot of money and issuing a lot of debt.

When you have a lot of foreign debt denominated in your currency – as the US does at about 45 percent of GDP – and a lot of debtors relative to creditors you want to create relief by having your currency depreciate.

When they go far enough with this it doesn’t yield anything in real terms. This means holding it actually erodes spending power.

It may also yield nothing in nominal terms as well. Central banks want to keep an inflation rate of at least zero, so real rates are very likely to be negative when they’re about zero (or negative) in nominal terms.

For foreign investors, they care less about real yield (domestic investors’ main focus) and more on the currency-adjusted yield.

If a central bank is creating a lot of money, this risks depreciating it. If the nominal yield of the currency and the depreciation rate exceeds the desired yield, it looks less attractive to own.

In the end, if you have an investment, you want to make money from it and nobody wants its purchasing power to decline.

When monetary policy is very stimulative, many traders want to be short bonds.

In the early stages of a recession, traders generally want to own bonds of reserve-currency countries, as they’re higher in demand. People want safety and liquidity in such circumstances.

Once there’s been enough cutting of interest rates and other stimulus, where nominal interest rates are pushed below nominal growth rates and debt servicing burdens are sufficiently eased, that marks the bottom in the economy.

The financial economy bottom (i.e., the markets) leads the real economy bottom (i.e., the economy for goods and services).

Bonds generally flip from being good investments to bad investments.

Nominal growth increases, which in turn typically raises yields.

Short cash

Cash is essentially short-term bonds. Often the three-month yield is taken as the cash rate.

Cash is generally always held short. People who have good uses for cash borrow it to create things. Borrowing means being short cash; debt is a short money position.

But the degree of borrowing changes. In a recession, people need to be defensive, so their borrowing is more muted.

When there’s more liquidity available, the desire to take advantage of cheap borrowing and rising asset prices increases in a self-fulfilling way.

Creditworthiness gets better. This helps increase lending activity. As lending improves, spending rises.

Capital investment rates also increase. This, in turn, makes it more attractive to use leverage to buy financial assets.

More people borrow and risk premiums decline.

At the same time, forward returns fall as asset prices rise. To obtain the desired return on equity, leverage ratios typically go up.

Cash might seem safe because its value doesn’t have a lot of volatility to it.

But cash is the worst thing you can have over time. It gets perpetually taxed through inflation by some amount per year. This adds up over time. And interest earned on cash is taxable.

Long stocks

All major currency devaluations help trigger stock market rallies throughout the world. One of the best ways to get risk assets to rally is to devalue your currency.

As the economy and corporate earnings grow, and interest rates are set at attractive levels (so there’s more money and credit creation to go into financial assets), stocks are generally in a very favorable environment.

Long-duration equities often tend to do particularly well. As earnings multiples expand, long-duration stocks benefit.

This often includes technology stocks, who may not be highly profitable now but are discounted to do so in the future.

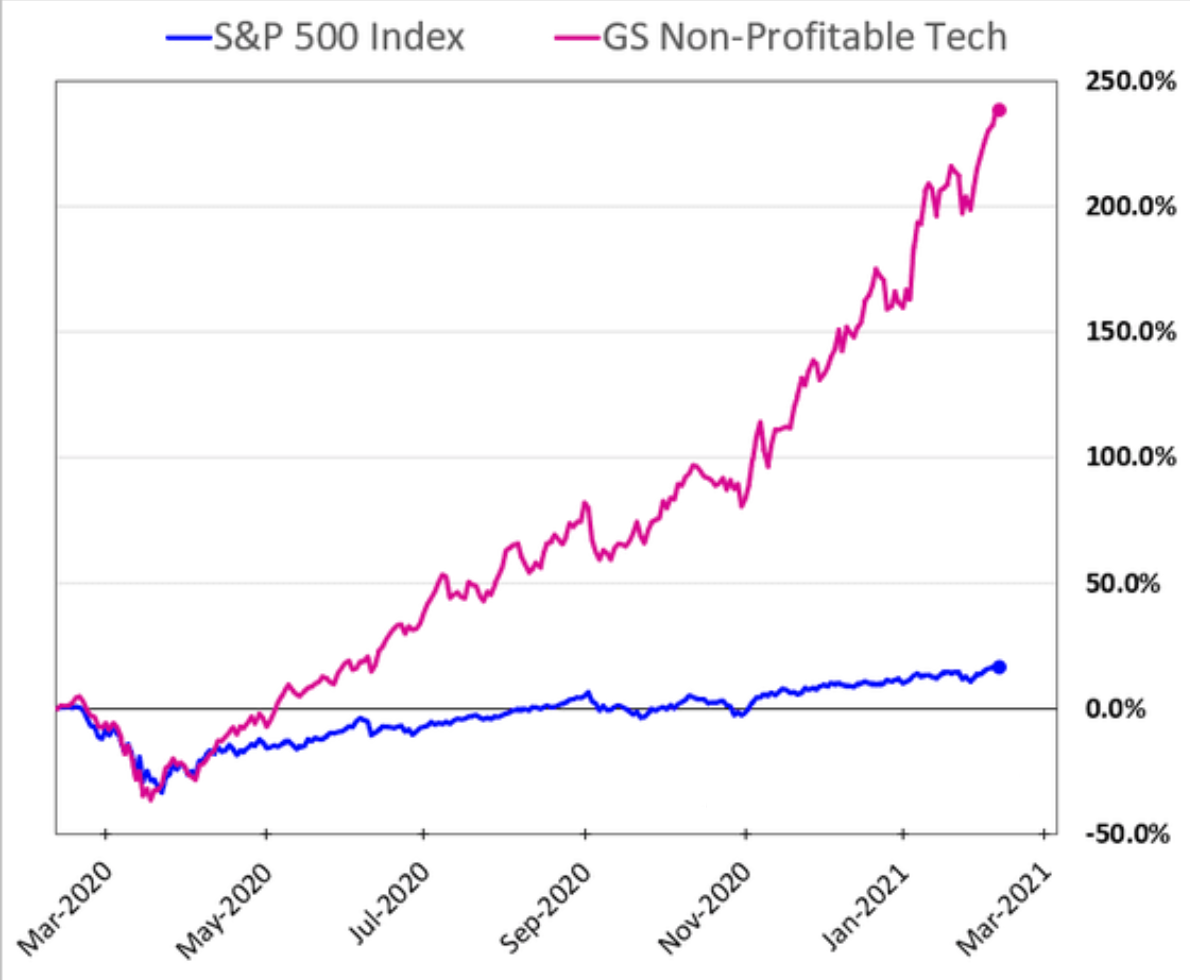

That can lead to the outsized performance of companies that aren’t yet profitable (some of which will inevitably never be).

Goldman’s Non-profitable Tech Index

Cyclical stocks may also do well, as more work opens up and unemployment drops. Things like heavy machinery and autos, which tend to see their demand get hit in recession, become higher in demand.

It also depends on the nature of the recession.

When interest rates can no longer fall much with zero rates throughout developed market economies, getting that offset from cutting rates is no longer very effective in getting a bottom in financial markets.

This makes market participants more leery of cyclicals and bullish on staples, where you don’t need a big cut in interest rates to help get a floor under earnings.

When interest rates are so low on cash and bonds to the point where spending power erodes owning them, more will think in terms of what else is there?

Bonds are the biggest single asset class, so if people want to get out of those, it’s going to go somewhere.

Stocks are inevitably one of those avenues.

Long commodities

Commodities can be thought of in a few different ways:

– a growth-sensitive asset class

– alternative currencies (i.e., medium of exchange, store of wealth)

– individual markets subject to their own supply and demand pictures

A reflationary picture is generally good for growth-sensitive commodities.

As economic activity picks up, there is more demand for oil, copper, silver, lumber, and other industrial commodities.

They can also be considered alternative stores of value.

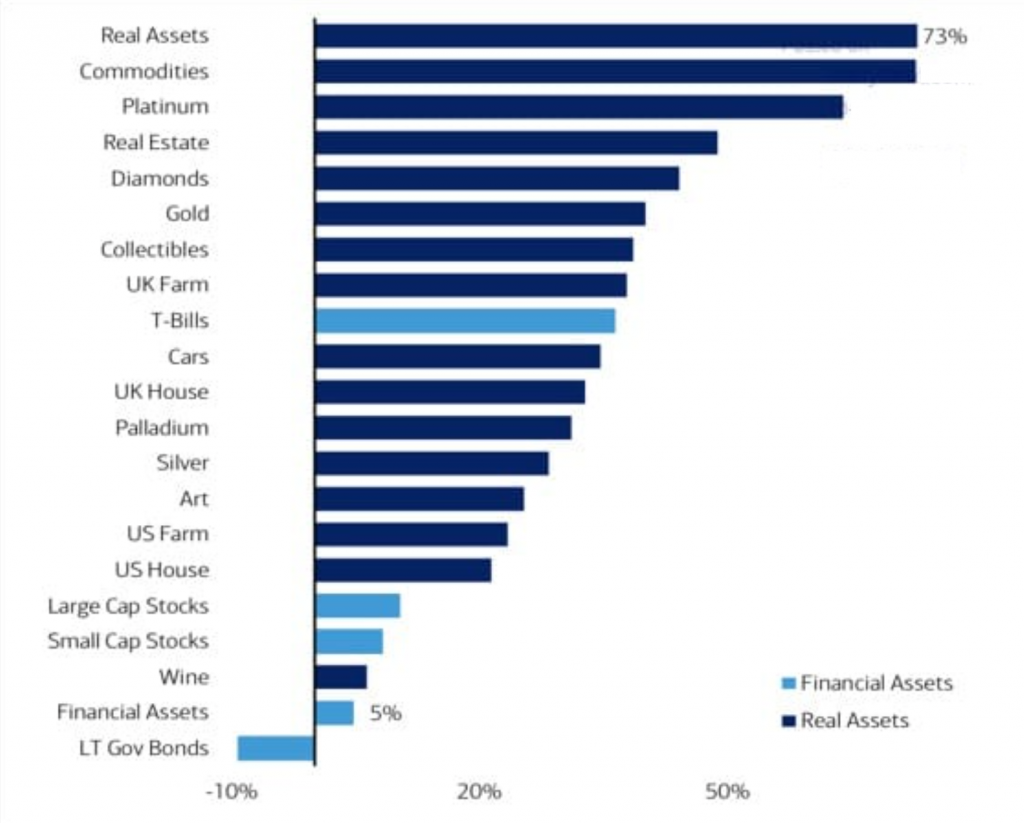

The desire for assets with inflation-hedge properties is also a strong consideration.

Traditional financial assets do best in lower inflation environments. This is because lower inflation feeds into lower nominal interest rates, which discount the present value of future cash flows.

Lower discount rates raise their present value (prices), all else being equal.

The chart below shows the correlation of real and financial assets with inflation since 1950.

Gold

Gold generally is one of the more popular commodities to go along with oil.

Gold functions more like a currency than a traditional commodity that gets consumed. It is not subject to traditional production and demand based on need-based consumption.

Instead, it’s a long-duration store of wealth asset. It’s the third-largest global reserve behind dollars and euros.

Gold is still generally under-owned by central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and other big players relative to the level of financial assets.

This is especially true when money is being created aggressively by central banks and debt issuance is extremely high. It puts the currency at risk for devaluation and the desire to find alternative stores of value.

To put things in perspective, the Fed in six weeks bought more Treasury bonds than it did in the decade-plus of Bernanke and Yellen as Fed Chairs.

The US has too much debt and other obligations to pay, about 15x GDP. Developed Europe and Japan are in similar predicaments.

All debtor countries are going to print money and depreciate their currencies.

Creditor countries are aware of this. So they’ll want to increase their non-USD reserves. Historically this has meant gold.

Debtor countries’ bonds are not attractive for the creditor countries’ lenders.

So, they’ll want to buy the assets they know they’ll need. Every country needs raw materials and hard assets – things they need and things that can be considered stores of value.

Commodities serve this purpose. That’s why commodities become more preferred to financial assets when the latter yields very little.

And not only do countries want to buy commodities, they’ll want to buy the commodity producers and manufacturers.

There is only a certain amount of inventory of commodities that can actually be held.

Certain equity investments, as discussed in the preceding section, make more sense as well, instead of the bonds of debtor countries being paid for with depreciating money.

A big part of commodity appreciation when it comes to how financial players think and when reserve management comes into play boils down to a lack of alternatives.

When many financial assets yield little or negative in real terms such that spending power is eroding, it makes a stronger case for holding non-financial stores of value.

Short dollar

As discussed, all of this fits with a short dollar theme. But this is more long-run, not necessarily short-run.

When you have a lot of debt, you can:

a) try to pull more money out of the economy through taxes, which has a limit),

b) you can cut spending, which isn’t very feasible because people depend on that spending for income and assistance (pensions, healthcare, and so on), and/or

c) you can print money if you have that ability.

Naturally, the last option is the one you naturally want. It’s the most discreet and the least politically charged.

It involves a currency devaluation.

But it also means a devaluation relative to what?

When other countries have the same problems it doesn’t necessarily mean a devaluation relative to these countries.

Moreover, during a drop in the economy, exports slow, so other countries have difficulty getting dollars and other reserve currencies. This creates a squeeze higher in the currency.

Then comes the printing of money by the central bank to get incomes back up, like in 2008 and 2020.

Both cases had massive policy support. 2008 was a famous example and 2020 dwarfed that because the fall in the economy was so sharp and severe.

The 2020 recession produced a larger deficit than the last six recessions combined – 1974-75, 1980, 1982, 1990-91, early-00s, and the 2008 financial crisis.

So, the currency devaluation doesn’t necessarily happen relative to other currencies. Devaluation often happens relative to the currencies of creditor countries with surpluses.

But a lot of the devaluation is seen with respect to assets like stocks, gold, and commodities.

The assets go up in money terms because they’re inherently denominated in that currency.

For example, gold is priced as a certain amount of money per ounce. If the value of money goes down, the value of gold goes up in money terms. It has little to do with gold itself.

That’s why gold’s long-run value is roughly equal to currency and reserves in circulation of a particular currency relative to the global gold supply.

It’s why gold often performs well in some currencies but not so well in others.

Currency devaluation also helps with inflation.

But when this happens in reserve currency countries with little foreign-denominated debt, little inflation is produced – at least at first – because what’s really happening is inflation is being negated.

What currency is safe?

Safe used to mean US Treasury bills, notes, and longer-term bonds. Safe used to mean cash in dollars, euro (European currencies more broadly), and yen.

Now, none of those currencies is particularly attractive.

The dollar is still over 50 percent of global reserves, the euro is around 15-20 percent of reserves, and the yen is around five percent. Gold is between the euro and yen in terms of its holdings as a reserve.

The least risk is not going to be in countries that have an excess of debt or too many obligations to pay.

All debtor countries will continue to print money. They’ll want to depreciate their currencies, and creditor countries will know this and are likely to want to shift to other types of reserves, like gold and rising currencies like the Chinese renminbi.

Geographic rebalancing

By and large, there’s a rebalancing of wealth going on between the Western hemisphere, which has debtor countries devaluing their money and Eastern countries, which have more normal interest rates and are seeing net capital inflows

The low rates on cash have spread to bonds.

Bonds are longer-duration fiat flows, so buying bonds essentially locks in those poor real returns. This, in turn, fuels this reallocation into other countries, assets, and stores of value.

What can go wrong with reflation trades?

Trades often don’t pan out as anticipated for a variety of reasons.

We’ll look at the main reasons why the standard reflation trades may not work out.

Short bonds

Bonds can only go so high in terms of yields before it hits the stock market and then the real economy.

Stocks are priced as the discounted present value of future cash flows.

Bond yields serve as one of the feed-ins into the discounting process (the other being the risk premium).

Rising bond yields reduce the present value math.

So, it’s unlikely bonds are likely going to yield higher indefinitely when there’s reflation into a highly indebted economy.

There’s a lot of debt relative to income and the economy can only tolerate yields that are so high before the debt servicing becomes a problem.

Central banks will try to take control of longer-term bond yields if it becomes a problem, known as yield curve control.

The US Federal Reserve has floated the idea, and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) have already adopted it in some form to prevent yields from rising too much.

A bond short in a reflationary environment can work, but in economies with strong central banks and central bank authority, it isn’t a trade that has necessarily unlimited potential.

Long stocks

When the yield on cash and bonds is extremely low, the discount rate at which the present value of future cash flows declines. When you don’t have a discount rate, you’re simply left with the risk premium.

If an environment where there are few alternatives, there’s a lot of liquidity and lending. Market volatility tends to decline, and the overall market risk premium declines as well.

This increases the present values of risk assets as well.

Historically, in the US over many decades we’ve been accustomed to an average cash rate of 4-5 percent, and an average 10-year bond yield of about 7 percent.

Returns of US Assets Since 1972

| Asset | CAGR | Stdev | Best Yr | Worst Yr | Max Drawdown | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Stock Market | 10.62% | 15.64% | 37.82% | -37.04% | -50.89% | |||

| 10-year Treasury | 7.11% | 8.02% | 39.57% | -10.17% | -15.76% | |||

| Cash | 4.66% | 1.01% | 15.29% | 0.01% | 0.00% |

If stocks yield about 3.5 percent above the 10-year yield, that’s a relatively high discount rate.

If your yield on bonds gets down to zero (as is the case in most of developed Europe, Japan, and close to that in the US) and the risk premium declines to just two percent, then your discount rate is only that two percent.

The inverse of that is the yield, or about 50x. That seems way out of line because recent history suggests 10x to 20x is more normal.

But circumstances were different. Economies weren’t as indebted, nominal growth rates were higher, and so interest rates on cash and bonds were higher as well.

The new macro environment creates a much higher stock market.

However, if something occurs that disrupts those low discount rates – such as higher inflation or more market volatility than causes a rise in the risk premium – the stock market is vulnerable.

Betting a lot in stocks is risky and having balance has never been more important.

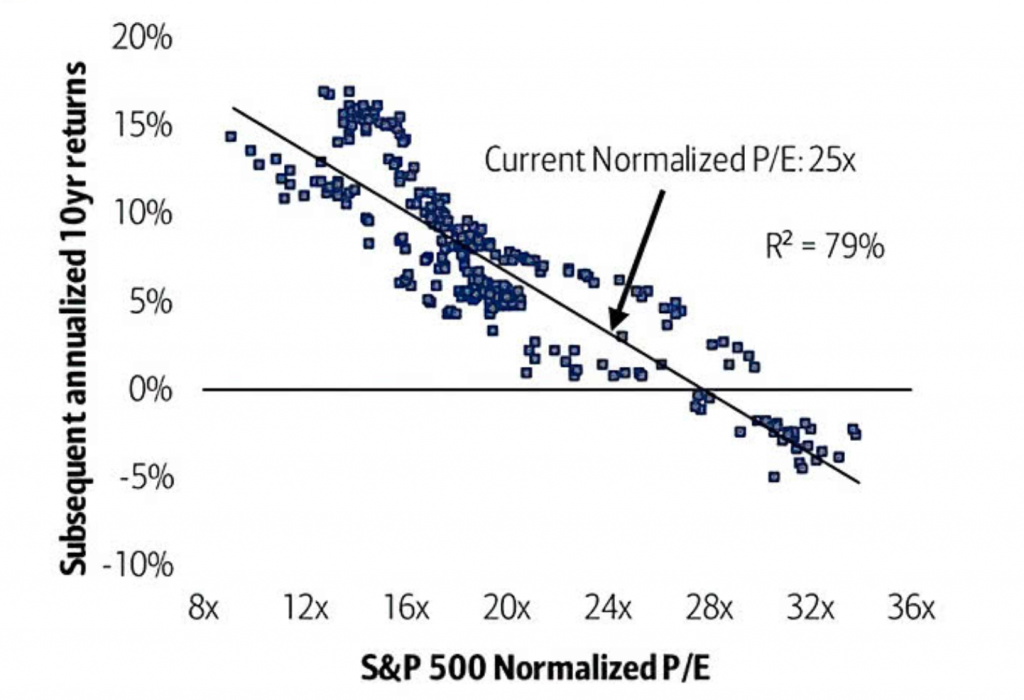

When earnings on stocks get into the 30x to 50x range, that’s only a 2-3 percent forward yield.

That’s not a lot of compensation for taking on that much volatility. Yields of 2 or 3 percent (or even a bit higher) can be wiped out in a day or two.

A lot of future gains are squeezed out of stock markets at those levels. It tends to yield lower future returns.

Valuation today suggests low price returns for equities over the next 10 years

S&P 500 normalized P/E vs. subsequent annualized returns (since 1987)

(Source: BofA US Equity & US Quant Strategy)

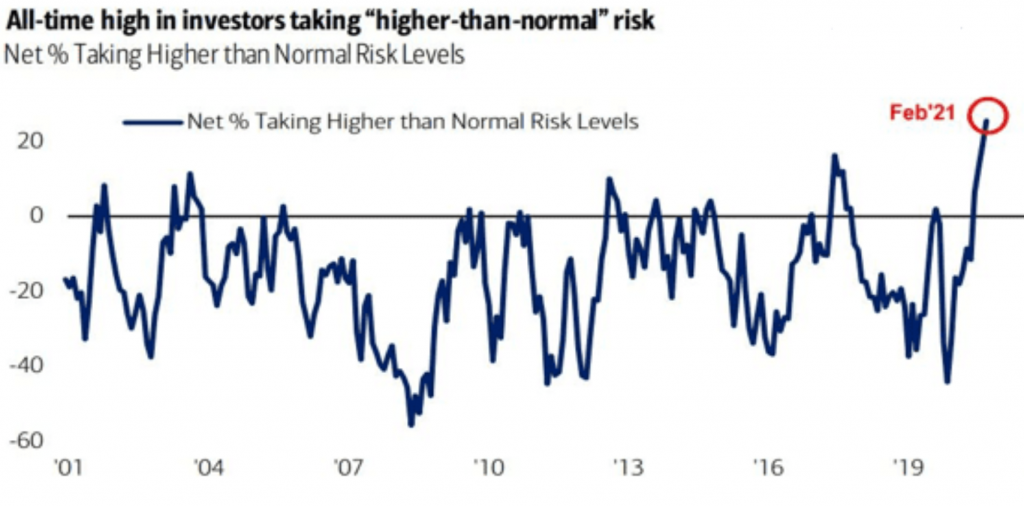

Fund managers running record levels of risk can result in crowded trades and more vulnerability to an unwinding of this risk.

(Source: BofA Global Fund Manager Survey)

Ultimately, earnings matter.

If the yields are low and the currency is unattractive, market participants are going to want to funnel that liquidity elsewhere.

Sovereign wealth funds are not in the United States. They’re largely in Asia, and for them to hold dollar assets is an increasingly risky position.

It doesn’t make sense for these non-US entities to own many Treasury bonds getting about one percent per year in return in exchange for a loss in the currency.

And the US will keep issuing these bonds as they become increasingly unattractive, which means the Fed will have to buy them. That puts more of a strain on the currency.

At the same time, if there’s a pop in growth and inflation, bonds are going to sell off, causing the yields to rise. This increases either interest expense, if the yields are allowed to rise. Or else they’ll have to print more dollars and take more of the brunt through the currency.

Long commodities

Commodities are growth-sensitive, so a growth slowdown relative to expectations can cause a long commodity bias to disappoint.

And all assets compete with each other.

If central banks decide to tighten monetary policy – or not ease policy faster than what’s discounted in the curve – this not only lowers forward growth and inflation expectations but can also increase the yields on safer assets.

If financial assets have a higher yield, then real assets look less attractive by comparison.

Generally speaking, the longer interest rates stay low the better you’ll tend to do with commodities. If rates start rising, that’s likely to slow momentum or reverse it.

Short dollar

Short dollar is more of a long-run trade because of the country’s financial position. There is too much debt and obligations relative to income.

The US will try to fill in these gaps by printing money. It won’t be commensurate with productivity gains, so the currency will devalue.

And other developed markets have these same issues. So it’s not as if the dollar is necessarily worse than the euro, yen, pound, or other developed market currencies.

It may have more downside because its use as a reserve (50-60 percent of all global reserves, debt, payments) is high relative to the US’s productive output (about 20 percent of global GDP).

Other currencies, including gold, are likely to take more of a role as a reserve.

There are also near-term divergences in policy and economic outcomes that are influential in the short-run.

So when people talk about shorting the dollar, there are various ways of expressing this outside literally shorting the dollar against another currency or basket of currencies.

It can mean basic borrowing. Margin debt is a form of shorting the currency.

Owning something like gold, or many commodities more broadly, can be a form of shorting the dollar. A weakening dollar is a tailwind for these assets, holding all else equal.

Stocks also have a positive reaction to a currency devaluation, holding all else equal.

Currency devaluations are good for stocks, good for commodities, and good for gold. They are not good for bonds.

An economic shock can also cause an appreciation in a currency. Lending decreases, exports slow and many countries can’t get easy access to dollars.

There’s a shortage relative to demand, pushing up the currency. This was the dynamic in 2008 and March 2020.

But in general, most traders don’t think enough in terms of their currency diversification. Most think in terms of what kind of stocks should they buy, and maybe diversification by asset class, and pay little attention to what kind of currency diversification they have.

When your spending power erodes a little bit year by year (and this dynamic is necessary to create debt relief in terms of the big picture) it’s important to think about currency risk.

Returns are not just asset returns, but asset returns plus currency returns.

A basic diversification strategy is simply putting about 10 percent of one’s assets into gold, a classic non-fiat, non-credit dependent asset.

Conclusion

Reflation trades involve four main themes:

i) Short bonds

ii) Long stocks

iii) Long commodities

iv) Short dollar

This the reflation playbook in simple terms.

Short bonds

Short bonds is a popular trade. But yields can’t rise too much otherwise you’ll have a squeeze on activity. Nominal rates need to remain below nominal growth. That way the economy can grow faster than the debt will compound.

(More accurately, debt servicing payments need to be held below incomes, new credit creation, and sales of assets to avoid a credit-related downturn in the economy.)

Long stocks

When a lot of liquidity is created, this is good for stocks. When cash and bonds are made unattractive, a lot of it will inevitably get into equities.

Stocks tend to rise for both earnings and liquidity-driven reasons. But as the cycle goes on, earnings yields decline.

If the central bank is still easing monetary policy, a lot of that money will eventually leave the country because the yields on domestic assets decline while the currency is being devalued at the same time.

Long commodities

A rebound in growth and activity is generally good for industrial commodities. Moreover, when real interest rates become unacceptably low, there is more demand for alternative wealth store-holds.

This can include gold and other types of commodities that are likely to correlate with goods and services inflation over a long enough time horizon.

Short dollar

Short dollar is a long-term trade.

You have about $300 trillion in total liabilities – i.e., among public debt, private debt, pensions, healthcare, other unfunded – against a GDP of just over $20 trillion.

Creating debt relief involves devaluing the dollar.

But short-term factors can prop up the dollar, and it’s not necessarily bad relative to European currencies or yen.

Commodities as alternative stores of value mix in with the short dollar trade, as many of them are denominated in USD.