Trading the Uranium Market

The uranium market is much smaller than gold, silver, and other traditional commodity markets. The buying and selling of uranium typically occurs among utility firms with nuclear power plants, mining companies, specialist traders, and a small number of hedge funds and institutional investors.

Money managers, however, are increasingly looking to get into more abstruse markets with the drying up of attractive yields in traditional stock and bond markets.

The Fukushima reactor meltdown in 2011 put a dent in the uranium market. Uranium, which is largely used to fuel nuclear power plants, has done little since even though the market could be much more glutted than it currently is.

Uranium’s two biggest producers are Kazakhstan’s National Atomic Co. Kazatomprom JSC GDR (also simply known as Kazatomprom) and Canada-based Cameco.

Together they’ve formed their own quasi-OPEC of the uranium market, exercising production discipline to avoid putting too much of the metal into the market.

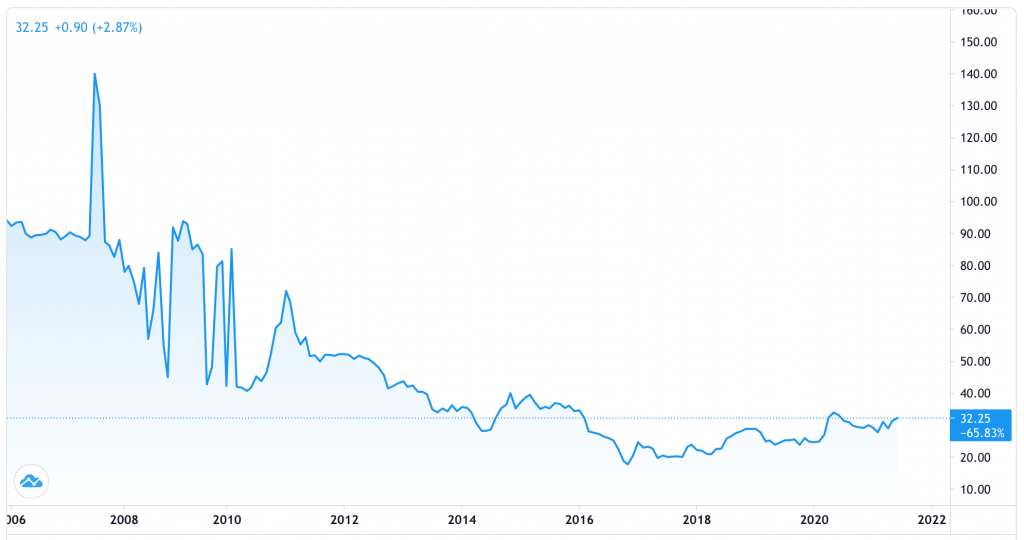

Uranium Spot Price

(Source: Trading View)

The uranium market as part of an ESG framework

Governments, including the US and China, also see a role for nuclear power as part of the push to lessen the world’s reliance on carbon. In that vein, you could argue that uranium is part of ESG-related shifts in some way.

Physical holdings of uranium

Physical holdings of uranium are rare. U3O8 is the lightly process form of uranium ore that’s typically traded physically. It is commonly called yellow cake because of its color and texture.

Laws are strict governing where and how uranium can be held. So it’s uncommon for uranium to be transported large distances to fulfill a sale.

U3O8 is stored in drums in specific facilities in the US, Canada, and France. Some prospective investors are cautious about the metal due to its potential to cause dangerous accidents, which also holds back the market.

Buyers and sellers will exchange the uranium on the spot and transactions are not reported publicly. About 60 to 80 million pounds of uranium are traded each year. At $30 per pound, this comes to around $1.8 to $2.4 billion in monetary terms.

Those with outright wagers on uranium believe that they’ll be able to sell the metal to utilities and others at a higher price in the future, essentially what’s known as a carry trade. Returns are uncertain, but the implied carry in annualized terms is typically in the mid-single digits.

Options can be embedded into sales agreements with utilities and other eventual buyers of the metal. For example, a utility might get a discount on uranium up to a certain amount in exchange for an agreement to buy more at a specific price at a later date. This can help traders juice the yields of their uranium trades.

Even though the raw material hasn’t risen much in price, uranium producers are seeing demand for their shares.

Unforeseen events

The risk of accidents is a source of concern for participants in the uranium market.

In June 2021, a report came out that the US government was looking into a report of a leak at a nuclear power plant in Southeast China (co-owned by two Chinese energy companies and French energy company EDF). The leak involved inert gases and not radiation.

The market response was comparable to the drop in uranium prices with the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident. Cameco shares dropped 10 percent on the 2021 news and 13 percent on the Fukushima news.

NexGen Energy dropped nine percent off the China gas leak. The URA uranium ETF dropped 6.5 percent.

The 2011 event turned into a major blow to the uranium market. Demand for the fuel fell and affected the industry for years.

How to get access to the uranium market

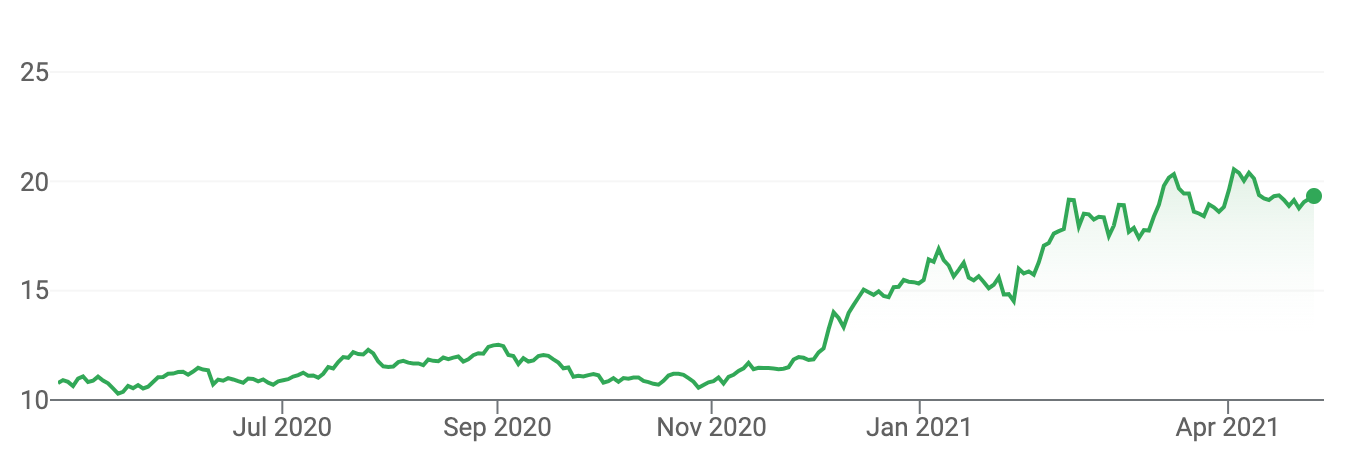

URA, the market’s largest uranium ETF, is comprised of various producers of the metal and other nuclear components, and saw a big boost from late-2020 to early-2021.

Global X Uranium ETF

Yellow Cake PLC is another company that commonly serves the purpose of acting as an ETF product.

Retail and institutional traders can buy uranium ETFs, uranium futures, and/or uranium miner shares.

Some institutions can buy physical uranium, though financial institutions are not as active in uranium as they once were.

Macquarie Group, an Australia-based investment bank, has the largest presence in the uranium market of any major financial institution. Goldman Sachs Group has a more limited uranium trading book than it had in the past. Deutsche Bank AG no longer supports uranium trading.

Uranium miners response to rising prices

Because of the price rise, miners looking to get into the uranium game are now raising money to buy uranium – i.e., the metal they’re trying to mine.

About three-quarters of uranium ore concentrate is sold to nuclear power plants in the form of long-term contracts. This is unlike most other commodity markets.

Companies that are looking to get into the uranium market are purchasing uranium ahead of time. This helps to:

a) build up collateral to get more ample and cheaper funding for new mines

b) to show nuclear plants that they have the uranium available when solidifying deals

This, in effect, helps take supply out of the market. Holding all else equal, that can help prices, which have been flat to down ever since uranium futures were established in 2007 on the CME Globex and CME ClearPort trading platforms.

Back in June 2007, uranium futures prices stood at up to $140 per pound. This dropped to $94 per pound in February 2009, and $72 in January 2011.

By the early 2020s, they mostly traded within a $25-$35 per pound range.

U3O8 is the most popular price for uranium, a weekly spot price for the semi-processed form of the metal.

The futures market for uranium

The futures market for uranium (NYMEX: UX) doesn’t have a lot of volume or liquidity. There is only a smattering of transactions in the spot uranium market each week.

The uranium spot market typically does less than 100 million pounds per year, though usually higher than 50 million.

The Global X Uranium ETF trades on the NYSEARCA under the ticker URA. ETF form is the easiest way for most individual investors (and even institutional investors in most cases) to gain access to the uranium market.

URA’s assets under management are typically around $500 million. That’s still only about half the size of the bitcoin market, for example. So it’s highly illiquid.

Uranium is difficult to own in size accordingly. It may be practical for a firm to own a couple hundred million dollars worth of uranium without being too big a part of the market. It’s not nothing, but it’s also not a quantity that would make up a material portion of an institutional portfolio.

Big producers’ and investors’ roles in the uranium market

Kazatomprom and Cameco have reduced production to give prices a boost.

To go along with investors’ desire for less carbon-intensive companies, this has boosted the stocks of smaller uranium companies.

In turn, they’ve been able to turn these higher stock prices into new capital, which they’ve largely used to purchase uranium – even well before they plan to mine it out of the ground.

Denison Mines Corp bought 2.5 million pounds of uranium for around $74 million. The money to do so came through selling warrants and stock.

In turn, it can use the uranium as collateral to get cheaper funding costs to develop its Wheeler River project in the eastern portion of the Athabasca Basin region in northern Saskatchewan, Canada, where it owns a 90% stake (with JCU owning the other 10%).

Once the mine is brought online, uranium can be sold to utilities. If the project runs into delays, cost overruns, or other unexpected events, the uranium offers a type of reserve asset.

The metal can also be sold if prices rise.

All in all, capital market enthusiasm for the companies producing uranium has seen a resurgence.

enCore Energy Corp (based in Vancouver, Canada) bought around 200,000 pounds of uranium in March 2021 after raising the equivalent of about $12 million. It initially targeted around $6.5 million.

Other investment vehicles are getting into the uranium market to act as a conduit for traders and investors who are trying to get better access to it.

In order to do so, these funds need to buy uranium using the proceeds from selling shares. Yellow Cade PLC is a London-based company that’s created an exchange-traded fund for uranium.

After raising $140 million from share sales, it bought around 4 million pounds of uranium.

How much does global conflict have to do with uranium demand?

We are moving into a period where there’s more global conflict. The world should expect to look to have a more bipolar global bifurcation with the rise of China in the East.

China has the largest share of global trade, and is behind only the US in the size of its economy and the size of its bond and equity markets. Its military is gaining strength. Its currency, the yuan (also known as the renminbi) is lagging, but this is natural, as existing reserve currencies tend to be entrenched even after their fundamental decline.

Broadly the US (and its allies) and China (and its allies) are in a variety of various conflicts along different strategic dimensions that will be with us for a long time:

You could also say there’s an internal war, that’s very important where people are divided in various ways.

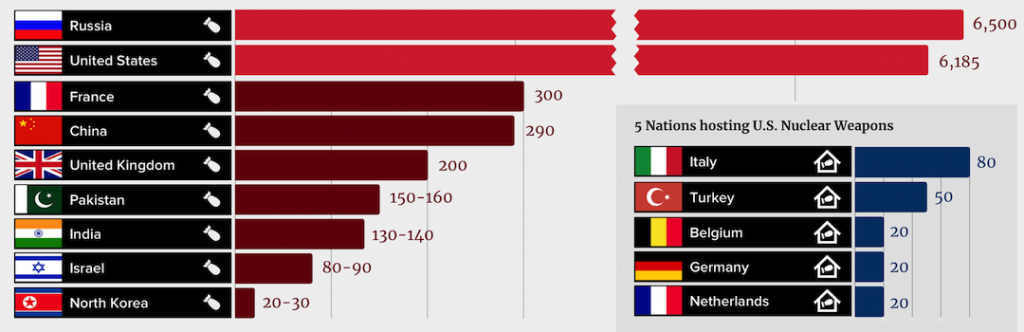

The US and Russia have the largest numbers of nuclear warheads by a wide margin, which has roots going back to the 1940s and 1950s.

(Source: icanw.org)

Russia is a natural ally of China. China can provide money and Russia can provide oil and a more robust nuclear arsenal than China has (in terms of the obvious benefits).

For investors, it’s in the back of everyone’s mind that stronger nuclear armament for the sake of protection could potentially boost the overall global demand for uranium.

Final word

Uranium is an industry that’s coming back after a long period of stagnation and decline.

You aren’t likely to see huge price increases in it given the dynamics of long-term contract settlements and little movement or speculation in the spot market. But with uranium-producing companies seeing a boost in value, it’s possible that the metal could follow.