Forms of Market Manipulation & How to Protect Yourself

Approaching trading from any narrow vantage point is difficult. Financial markets are a mix of different players with different motivations and different sizes.

Some traders will use price levels and a mix of different indicators of where price and/or volume has been in the past. While markets can be responsive to those in a self-fulfilling way simply because other people use them, there are many other different types of approaches.

Value investing is a common strategy that makes sense in terms of what to buy, especially over a long time horizon if such “value” is correctly determined. But there are momentum traders, market makers, and other buyers and sellers, including central bank actions, that make the game difficult.

The price of a security is just the amount of capital spent on it divided by its quantity. So, the types of buyers and seller, their sizes and motivations are going to do a better job getting at understanding why a market is trading where it is and what’s going to happen to going forward. That is, relative to more narrow ways of thinking about markets than something like price levels or notional equilibrium value.

The case of the tech price run-up in August 2020

There’s also the topic of market manipulation, where markets move in ways that have nothing to do with traditional analysis.

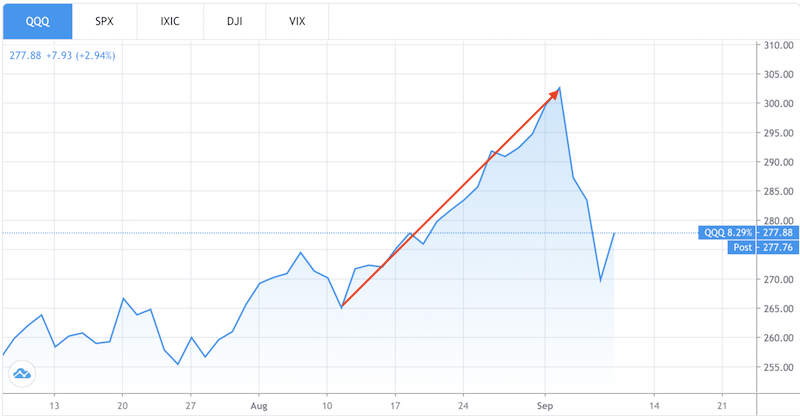

The 14 percent run-up in tech stocks from August 11 to early September 2020 was determined to be a “whale investor” in Softbank.

(Source: Trading View)

The Japanese investment conglomerate bought billions of dollars’ worth of call options in stocks that they owned.

Buying call options forces those on the other side of the trade (market makers) to buy the underlying shares to hedge their delta and/or gamma exposure.

Holding all else equal, this causes the share price to increase and can potentially set off a flywheel effect.

Namely, more call option demand leads to more hedging (i.e., buying shares), which leads to more share price run-ups, and further hedging and so forth.

Many tech names eventually fell sharply in early September once Softbank was determined to be behind this, as can be viewed in the above chart.

Is this market manipulation, or is just a large player trying to use its size to exert influence?

Market manipulation

Manipulation has been part of the financial markets ever since capital markets were established.

Market manipulation is a common complaint among those who might look toward external factors negatively impacting their trading or investing results.

They might believe that well-heeled market participants or insiders are manipulating trading on the exchanges for their own benefit at the expense of those who have less information.

Unfortunately, whenever there is money at stake there will be those who try to exploit any type of “loophole” or advantage for their own means, whether it’s legal, illegal, or somewhere in between.

One shouldn’t develop an unhealthy mindset that markets are “rigged” and “manipulated” and always adversely impacting one’s results.

Instead, while market manipulation may exist in some form, success in the markets is still heavily tied to your own knowledge, thought, analysis, and accumulated experience.

Various forms of market manipulation are part of the structure of financial markets. How different types of well-capitalized investors play the game (legally) isn’t within one’s control.

For example, it is common for professional investors to prey on other professional investors. If someone becomes a material part of their markets, that sets up the potential for someone else to squeeze them out of those positions.

Long Term Capital Management became a highly leveraged player in the relative value space in the late 1990s. They became a big part of the US Treasury futures markets in particular.

When spreads began to widen in those trades, other players believed they could trade against them, widen the spreads further and eventually squeeze them out. (They eventually did. And this had systemic implications. Given LTCM’s huge size with a portfolio of around 10 percent of US GDP at the time, it threatened the entire financial system.)

This type of “market manipulation” and predatory behavior goes on all the time and is expected. This is why hedge funds cap their size after a certain point and close their funds to new investment.

Know that this type of market action that has nothing to do with the fundamental value of the underlying instrument or security can work for you, against you, or in no particular direction either way.

It’s also important to remember that the range of unknowns in the market is always going to be greater than the range of knowns relative to what’s discounted in the price.

This is why strategic diversification and adopting a risk-neutral asset allocation as your starting point is a prudent thing to do.

Also, market manipulation in its various forms is most disadvantageous for shorter term traders rather than those who have holding periods over months, years, or even decades.

Valuations can stay out of whack for elongated periods of time – and in a way that makes them difficult to profit off of, as short sellers can be squeezed out of positions if bubbles inflate further. However, most issues are short-term in nature.

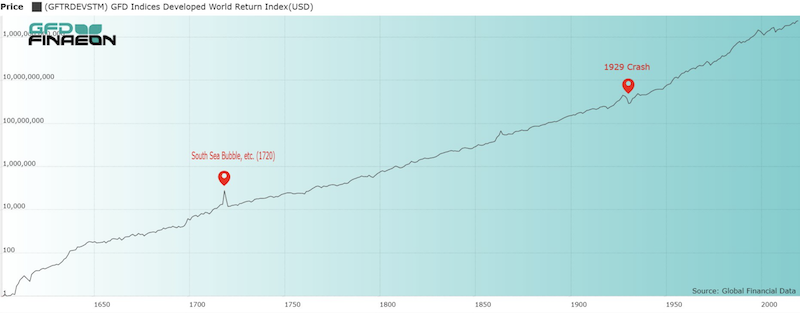

Looking through time, even major events like 1720 (e.g., South Sea bubble) and 1929 (US equity markets down 89 percent peak to trough) look like blips on the radar.

Generally, the best way for traders to protect themselves from financial market manipulation is to have a large bulk of their portfolio set for the long-term.

In general, it is a bad idea for smaller players to bet on what’s going to be good and bad and trying to operate on very small timeframes with their positions.

Competing directly in the markets against well-capitalized institutions that generally have an information advantage isn’t the best idea. There’s always somebody else on the other side of any trade and a reason why they’re doing it. And they’re probably sophisticated.

Trading is like sitting down at the poker table against those who are the most experienced and well-strategized players of any in the world. The biggest investors didn’t get to where they are on accident.

Those who don’t treat it like a business might win a few hands here and there, but they’re going to find it very difficult to win consistently. History shows that a few players make a lot of money in the markets and most lose (relative to a benchmark).

Some brokers have built their business model around the concept that retail is less informed than the average market participant, and sell their order flow to market makers.

In certain cases, that’s how trading, in some cases, becomes “free” or no commission. (Others still nonetheless compete by providing excellent trade execution.)

Different types of ‘market manipulation’

Understanding the various forms of market manipulation can help to better inform your trading and investing decisions:

Pump And Dump

“Pump and dump” is one of the most common financial market manipulation tactics.

A pump and dump is executed to try to increase the price of a stock quickly. The entity promoting the pump will try to liquidate the position before the stock price tumbles once they and any co-promoters start selling their shares.

It is very common for the “promoters” (i.e., manipulators) of this scheme to do this on stocks with very small market capitalizations than larger ones, often called micro caps or nano caps (generally those with less than $100 million in market cap).

This is especially true given the pump and dump tactic largely depends on convincing retail investors to buy up the stock.

So, it is important for the prices of these stocks to move much more easily on a dollar for dollar basis than larger cap stocks, which are very hard to move materially with retail money.

It can be thought of in supply and demand terms.

When the supply of something is limited (i.e., lower float stock), a sudden surge in new money being spent to acquire its shares will increase its price more relative to a higher float stock.

The general tactics and sequence behind a pump and dump schemes goes as follows:

i) Promoters will use various media and communication platforms to promote a particular stock. This can include blogs, social media, message boards, newsletters, email, native ad platforms. Basically anywhere there is an audience interested in stock trading.

Some platforms with editorial oversight will pay special attention to any submissions of articles or write-ups on companies with a market cap below $100 million to look for pump and dump schemes.

This will involve writing recommendations extolling the company and the underlying stock. It will generally include any positive strategic, operational, and/or financial attributes about the company, true or not.

It is generally easier to pull off with respect to a sector that’s currently seeing, or has recently seen, frenzied buying.

This could include blockchain, cryptocurrencies, “alternative harvest”, electric vehicles, artificial intelligence, and tech in general.

Practically anything that’s easily prone to distortion due to narrative – things that are difficult to value (e.g., AI) or supposedly the next big thing.

Sometimes they are advertised as “this is the next [insert already successful or well-known company]”, though not all ads of that variety are pump and dump schemes.

ii) If successful through a coordinated advertising scheme, retail buyers are drawn into the stock. Marketing is generally dispersed all at once across all channels instead of the course of days.

This pushes volume and the stock price higher, sometimes by several hundred percent, often within a few hours.

Successful pumps are generally sharp and sudden.

iii) Once the advertising material has been released, the pump will begin running out of gas after the initial surge of momentum. The trend in volume will plateau.

This is when promoters will begin selling their shares to the new buyers who are later, also known the “dump” phase. This secures them a profit.

Naturally, once the dump phase begins, this will cause the stock or security price to fall.

Others who bought in not affiliated with the scheme will try to exit as well. Oftentimes, this causes price to return back to where it was before the pump and dump scheme started.

Those who bought in midstream or toward the top will often see big losses.

How to avoid pump and dump schemes?

Nano cap and micro cap stocks are often called “penny stocks”.

Many of them have very thin volume and trade at very low prices, sometimes even low enough to give credence to the penny stock name ($0.01 or even less per share).

These are the most vulnerable to market manipulation because it doesn’t take much money to move them.

Nano cap stocks are typically defined as those that have market capitalizations of less than $50 million. They are small to the point where there is generally very little institutional money in them. Some institutions effectively can’t put money in these stocks in any material quantity without moving the market against them.

Micro cap stocks are also frequently looked at for pump and dump schemes. These commonly have market capitalizations in the $50 million to $300 million range, especially the aforementioned types of companies in verticals most prone to stories.

In general, pump and dump schemes can be avoided by buying stocks of market capitalizations that are above $100 million. Stocks below this market cap are thinly traded and especially prone to manipulation that can derail any good thesis.

Any stocks that are priced at low dollar per share amounts – generally under $5 (little to no institutional representation) – are also at risk.

Promoters know that retail investors will be able to buy shares in bulk.

Moreover, they will also be more likely to perceive them as cheap. Some newer traders erroneously believe that buying 10,000 shares at $1 apiece is a better deal than buying 10 shares of a $1,000 stock, for instance.

Most institutions also can’t buy stocks that are below $5 per share due to restrictions.

It should also be noted that if by any chance you do own a security that is subject to a pump and dump scheme, it doesn’t mean you’ll lose money as a result of it.

Pump and dump involves buying a stock rather than selling it short. More people are inclined to buy stocks than short them. Most inherently believe that stocks will go up over time, given the positive risk premium over cash.

There are such schemes involved in spreading negative rumors or information about a company. But that’s something we’ll cover in the next section on false information.

Traders can also protect themselves from pump and dump schemes if they do own smaller cap stocks by using take-profit levels. In certain cases, traders can fortuitously benefit from one.

Take-profits are common among many types of traders to get out of a trade when an instrument hits a certain price level.

For example, value investors will sell stocks when they believe it has hit a price that represents its fundamental or fair value.

For instance, if a trader buys shares at $10 and believes that the fair value of the stock is $15, one could set the take-profit level (which is basically a sell order) to that price.

In the event that the security is ever subject to this type of manipulation, one’s position could be profitably liquidated before the dump phase of the scheme occurs, dependent on how high it goes. This would effectively put you on the same side as the promoter.

Cases of pump and dump at a larger scale

Larger stocks can be manipulated higher as well. Sometimes even those with tens or hundreds of billions of dollars in market capitalization.

This can be due to prominent investors stating their opinions publicly or due to insiders making new information public.

These matters are all subject to securities law, no matter what capitalization the company is. Pump and dump schemes of any size are illegal. However, that doesn’t mean they won’t happen.

Those who intentionally spread false information, or induce others to trade on false information, are committing securities fraud.

The most famous example of securities fraud was a contrived buyout offer for Tesla on August 7, 2018.

CEO Elon Musk falsely proclaimed on Twitter that he had funding to take Tesla private at $420 per share at a time when the stock was trading about 20 percent below it.

There was no such offer.

Musk, who has a well-documented history of battling short sellers publicly and had promised to “burn” them for betting against Tesla, made up the supposed $80 billion buyout.

The stock initially entered into the “pump” phase after the tweet.

But it faded after the market grew skeptical of the possibility given the size of it, the extreme valuation for a company with poor financial metrics, a very limited number of market players who could realistically take it on, and any threat a leverage buyout would do to its already tenuous cash flow position (i.e., no EBITDA to pay down the debt for any such offer).

The stock eventually fell below the “pre-pump” price once the market realized it wasn’t true and the fact that criminal securities fraud charges would very likely be filed.

The next month the Securities and Exchange Commission charged Musk with criminal securities fraud, asking him to step down as Tesla’s CEO and chairman and pay remuneration for damages associated with his claims.

Eventually Musk and the SEC settled the charges for a fine, his stepping down as chairman for a period of time (but keeping the CEO role), appointing new independent board members, and having a certain level of oversight of each tweet he sends out.

False Information

Sometimes the information out there about a particular company – and therefore its stock, if it’s publicly traded – in the media provides a misleading account of what’s actually true.

The more popular term today, of course, is “fake news”, which became popular with Donald Trump’s terminology for news that’s distorted or he disapproves of, and has since grown into a general expression for any false or misleading news.

Those of influence within the investment community have the ability to move financial markets through their words and sometimes through filings (e.g., Berkshire Hathaway’s 13-F filing of stocks it bought in the last quarter).

It could include a popular investment manager commenting on a particular stock, industry or asset class, or a piece of information in a widely circulated publication like the Wall Street Journal or Financial Times.

Popular institutional investment managers, promoters (discussed in preceding section), and media publications depending on their level of trust can influence news and information streams about various companies.

Of course, this can also include monetary and fiscal policymakers. Federal Reserve communications are planned out ahead of time, with words carefully chosen given their impact on markets.

This can include comments on broad macroeconomic metrics, such as central bankers commenting on the future path of interest rates.

All of which is collectively known about a particular security is known as the “consensus” and already discounted into its price.

Therefore, if that narrative is altered through any material information through whatever communication channel, it can shift the price.

This can work for you and work against you. No security, instrument, or market is immune to it, whether it be stocks, currencies, commodities, rates, or others.

Being well-diversified among asset classes, countries, and currencies can help mitigate the inevitable swings that occur.

False information intended to hurt a stock’s price is also governed by securities laws. Short sellers, like CEOs, cannot trade on, or induce other people to trade on, information they know to be false.

How to avoid false information?

It’s not practical to plan for and avoid false information entirely. Stocks are especially prone to false information given their valuations can easily be driven by narrative (especially in tech, buzzword verticals, and other areas where earnings are speculative or not well established).

This naturally impacts everyone and not just smaller investors.

At the same time, if false information introduces inefficiencies into the market, this provides traders with opportunity to take advantage.

John Williams’s July 2019 speech at the New York Fed was broadly misinterpreted by the market that the Fed would ease monetary policy more aggressively than was then priced into the curve.

Rates traders who didn’t view the speech as a call for more aggressive policy easing could have shorted the nearest term fed funds contract to take advantage of the mispricing.

In the stock market, Facebook’s stock has frequently come under pressure over data privacy issues and many investors has fled believing it represented a material threat to the company’s business.

At the same time, Facebook is a massively profitable company with large social influence globally that will continue to innovate in collecting data and modifying its algorithm to deliver ads in a highly targeted and effective way.

It is largely assumed, provided enough time, that the facts governing a company or particular market will come out over time. This provides another argument in favor of taking longer term approaches.

‘Painting the Tape’ or ‘Spoofing’

“Painting the tape”, also known as spoofing, is a term that goes back to when stock prices were transmitted at regular intervals through ticker tape.

This involves traders setting buy or sell limit orders in securities at a certain price to make it seem like they have the intention of trading it there. Other traders can look at the order book (i.e., level II data) and see all this information tracked electronically on the exchanges.

However, in reality, those setting the orders have no intent in following through with these orders.

It can still manipulate a market because limit orders in size can influence the activity of other traders. The order size has to be large enough to attract the notice of other traders. They might believe it signals that somebody of significant size (“smart money”) has information that they don’t.

For instance, if a stock is trading at $100 per share, a trader may try to influence others traders into thinking that the share price is rising by putting in a buy order bid for $100.20.

This might be done in the hours leading up to an earnings announcement to provide a false signal about which way the results might go. After all, if somebody seemingly wants to trade in size before an announcement that could suggest they know what’s going on.

As buyers join in thinking the signal is genuine, this generally causes more buying as volume tends to attract other traders.

The spoofer may then change course by canceling the buy order at $100.20 to put in an order to short-sell at $100.20 instead. This order is executed.

Through this scheme, the trader was able to get in at a more advantageous selling price – $0.20 or 0.2 percent above its previous price before the spoof. In other words, theoretically closer to a price worth selling at.

Sometimes traders will spoof multiple times.

For example, assume we have the same circumstances and the trader did the same thing as in the first example:

i) Stock is trading at $100

ii) Trader puts in a bid to buy the stock at $100.20 in a large quantity, catching the notice of other market participants and bringing in other traders who believe it could mean that the current price of $100 is unlikely to stay

iii) Trader will cancel his buy order at $100.20 and at the same time offer to short-sell the stock at $100.20

At this point, the spoofer may look to try the reverse process by doing the following:

iv) Offer to short-sell at $100.10 in the same or similar quantity as above, drawing in others to sell their shares and pulling price back down

v) The trader will then want to cancel this short-sell order at $100.10 and simultaneously buy at $100.10

The net result:

The spoofer short-sold the stock at $100.20 and covered the short by buying at $100.10. This locked in a profit of $0.10 per share.

Traders who do this repeatedly and with excellent execution and the requisite volume to influence other traders can net large profits in a short period of time, especially if done with leverage.

Spoofing, as one might expect, is illegal. But it can also be hard to determine when it occurs. Regulators increasingly need to use forms of statistical analysis and analysis of communications in order to ascertain whether any illegal actions took place.

There are also legitimate reasons why traders might cancel large orders that they had intended on placing should prices get to those levels.

Market makers who provide liquidity to markets are also monitoring the supply and demand provided to certain markets.

Switching frequently from buy to sell orders can make sense in the process of matching buyers with sellers, or what’s known as making a market.

Moreover, some traders may not be trying to “paint the tape” but attempting to not give off information about the size of their trade. Multiple orders may be made at different prices.

High frequency trading (HFT) is a frequent topic of criticism because it can be used to manipulate the markets in a similar or identical way to spoofing.

HFT relies on algorithms and computers with ability to crunch massive amounts of data as in-feeds on when to enter and exit trades in the market. The black box nature of what they do conceals what exactly is taking place, though these strategies are broadly classified as a type of statistical arbitrage.

The nature of technological innovation in the market has called for increased regulatory scrutiny.

For instance, there is the uptick rule, which requires that any short-sell of a stock can be executed on an uptick from the previous price. For stocks this is one cent – e.g., $100.01 per share instead of $100.00.

This is designed to prevent short sellers from entering a market and pushing prices lower in a self-perpetuating way, which could undermine confidence in a market.

Some regulators and politicians have proposed that there should be a minimum amount of time that a person should be required to remain in a trade, such as one one-hundredth or one-tenth of a second.

Many trades executed purely through HFT algorithms last for milliseconds. Some have called for tax penalties on high frequency trading in such a way that HFT becomes nonviable.

However, this would make markets less liquid. Much HFT activity is providing liquidity to a market. This helps close spreads and makes trading costs cheaper for everyone.

How to avoid spoofing or painting the tape?

Spoofing is purely a short-term type of strategy. Its significance is virtually nil for those holding securities over the course of multiple days or longer.

Most HFTs compete with each other and not against those with longer term time horizons. Those in the latter group don’t have any need to be concerned that spoofing or HFT patterns have an influence on a timeframe relevant to their own trading.

Trading firms who do operate on shorter timeframes also develop software to ensure that they aren’t being deceived by those trying to paint the tape.

Bear Raiding (sometimes known as ‘short and distort’)

Bear raiding is the process of forcing a stock price down to trigger the stop-losses of those in open long positions.

The liquidation of long positions causes even more selling. The goal is to create feedback loop that runs in a self-perpetuating way.

It can be a form of directional manipulation and also put into practice through false information.

Traders can either set the process in motion by short selling the stock themselves and/or by sounding off on negative information regarding the company publicly.

As mentioned in a previous section, spreading false information about a company in an attempt to downwardly manipulate the stock price is typically considered illegal, especially when knowingly false.

But it can be difficult for regulatory authorities to prosecute, as the burden of proof is reasonably high and it depends on the extent or the influence of the person doing it. Is it a major investor with a lot of clout or is it a more anonymous personality?

Bear raiding has been common throughout history.

For example, in 1997, Thailand had a debt crisis where they borrowed too much relative to their availability to service it.

Foreign investors began to pull their capital from the country in response to an impending financial crisis. This had knock-on effects in surrounding Asian economies and their respective currencies, including the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Hong Kong.

Currency speculators “bear raided” these countries’ currencies, pushing them down.

To try to offset this activity, the central banks of these countries raised their interest rates.

Rising interest rates can help increase the yields of cash and local currency credit and equities. This helps create demand for them and therefore boost the currency, holding all else equal.

However, interest rates are also used as part of the calculation in determining the present value of cash flows (that make up stock valuations).

When interest rates increase without a simultaneous increase in the earnings expectations of these companies, stock valuations will drop.

The stock markets in these countries began falling. This, in turn, spread to other countries as well.

Speculators increased the pressure to profit off the opportunity in one of the more prominent “bear raid” episodes of the late 20th century.

Are bear raids really manipulation?

Financial markets are a way of expressing an opinion about how the world works in some form.

“Speculative attacks” are not necessarily manipulation but are often simply a way of making a bet on one opinion of reality in some way or another.

A popular example is the shorting of the British pound (GBP) in the early 1990s.

At this time, the British pound had broadly kept in line with the German mark.

However, the Bank of England didn’t have the foreign exchange reserves available to keep the pound within the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM).

The ERM acted as a unification precursor to the European Monetary Union, which created the euro currency. The rate was kept at 2.7 German marks per pound.

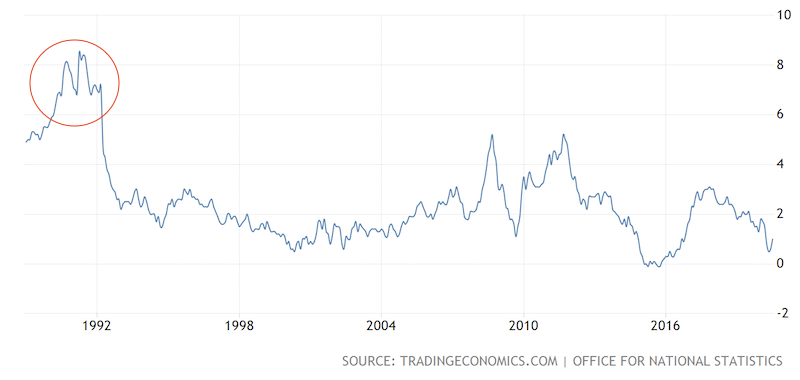

The UK needed higher interest rates given its inflation rate had gotten out of hand at approximately 8 percent. (Note the early 1990s portion of the graph below.)

To that point, because of the benefits of having greater monetary and economic cooperation between European countries (including building a better reserve currency), the UK had agreed to keep its interest rates artificially low.

However, once price pressures and inefficiencies pick up to a high enough extent, it’s not a sustainable set of economic conditions.

The Bank of England had to buy its own currency with its foreign reserves to keep the pound pegged to the mark.

Many traders, most notably George Soros’s Quantum Fund due to the size of his firm’s bet, believed (in reality, knew) that the Bank of England couldn’t sustainably do what it was doing to fight natural market forces.

So, they decided to short the currency.

The BoE tried to counter by raising interest rates to attract inflows into the pound, but it had little effect in convincing the market of what was an economic reality. The Bank of England would run out of reserves and they’d have to let the pound depreciate.

The British government eventually relented and let the pound fall out of the ERM.

This is a prominent illustration that government intervention in currency markets is far from a bulletproof situation.

This is particularly true in scenarios when their desires about the way they want things to be aren’t consistent with reality. Exchange rate regimes that aren’t consistent with economic fundamentals are not sustainable and will inevitably fail.

While the trade is maybe the most famous “bear raid” in history, it was simply acting on how reality works.

‘Short and distort’ vs. ‘Pump and dump’

Bear raiding, or “short and distort”, is less common than “pump and dump”. The latter generally provides more upside and less accountability. Most people have bullish biases and writing or saying favorable things is a lot easier to do.

Bullish opinions are less controversial and it’s also easier to be right on them in the stock market. Shorting the underlying stock has a maximum return of 100 percent, while being long has unlimited upside.

How to avoid bear raids?

Bear raiding is very difficult to do stocks with large market capitalizations. It takes very large amounts of capital to move those markets in any material way.

Accordingly, the general idea here remains the same as in previous sections. Stocks and securities with thin liquidity and low market capitalizations are more easily subject to manipulation.

Avoiding stocks with low market capitalizations and securities and instruments that have less liquid markets can be prudent, as these are more easily manipulated than markets that more liquid.

Wash Trading

Wash trading is a type of spoofing.

Wash trading is a type of activity where traders (who are typically large parts of their markets) will buy and sell securities back and forth either to related entities or to themselves. This is designed to increase the volume in a certain market and attract interest from other market participants.

It often involves the same or a related party selling shares through one broker and buying them through another.

This has the effect of boosting volume but producing no net effect on price. Hence the term “wash” trading.

Artificially inflating volume creates the illusion that legitimate trading activity is occurring. This causes some investors to join in believing it’s a “hot” market.

It’s a tactic used to drum up interest in particular securities. Wash trading is illegal and has been in the United States since 1936.

Many traders who study technical analysis, or general market dynamics and behavior that can help predict the future, believe that price follows volume.

Some traders might view rising volume with no rising price as a signal of a future possible rise in price.

Initially buy orders might be offsetting sell orders, with no net change in price until this neutralization eventually gives way to price moving in one direction or another. Volume tends to trend over time.

For instance, is price has been trending lower on thin volume and volatility begins to increase, many traders might interpret this as a potential reversal signal.

When it’s occurring through wash trading, however, the trading activity is not legitimate transactions being made.

Wash trading can be used to not only create the false illusion of demand for a stock or security, but also to generate commissions for brokers. These largely depend on trade volume and margin fees.

Wash trading may entail not just a high volume of trade activity to generate commissions, but seeing this trading activity done on leverage to generate interest fees.

This may be used to compensate the broker-dealer for a particular reason.

Some prime brokerages, for example, need to generate a certain amount of business from a client each quarter or year to make the arrangement viable. This includes fees on commissions, financing, research, and other services.

Wash trading, though again illegal, is one way to satisfy this requirement. This allows the trader to access to certain markets and financing terms that wouldn’t otherwise be accessible through standard retail trading accounts. It can, in effect, pay for itself.

Some involved in wash trading may also have a financial interest or ownership in a brokerage.

Wash trading in cryptocurrencies

Wash trading has been prevalent in the cryptocurrency markets.

The bitcoin trading platform Bitfinex valued itself on the basis of their earnings. For a brokerage, this is generally proportional to trading volumes.

In order to raise funding, Bitfinex offered a form of tokens that could be converted into equity in the company.

Unfortunately, this created the incentive to engage in wash trading. People on the Bitfinex platform bought the tokens and sold them back and forth to themselves or related parties. This generated commissions for the platform while increasing the value of their tokens.

The Bitfinex platform did not have protection against wash trading built into its trading engine. Given that trading commissions were the majority of Bitfinex’s valuation, one might ascertain that this exclusion wasn’t accidental.

How to avoid being impacted by wash trading?

As wash trading is a form of spoofing, this again affects mostly short-term trading activity.

It is also market neutral in nature, as all the activity is essentially buyers and sellers netting each other out at the same price. So, from that vantage point, while it might boost volatility (and the prices of derivatives, for example), on its own wash trading is not meant to move markets in one direction or another.

Longer term traders, once again, have little to fear regarding having their portfolio undermined by wash trading.

Also, larger stocks (market capitalizations of at least several billion dollars), and markets with larger volume with a diversified mix of buyers and sellers, have fewer issues with wash trading behavior as it is much more likely to represent a tiny fraction of overall trading activity.

Central Bank Actions

This is controversial as central banks are not manipulators per se, but simply fulfilling a particular statutory government mandate.

Broadly, central banks help guide the money and credit creating capacity of the economies in their respective jurisdictions.

While it is a form of central planning, central banks are fundamentally designed to be a liquidity backstop and help provide supportive interest rates to maximize output within the context of price stability.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the role of central banks in the financial markets has grown larger.

Developed markets have cut interest rates down to very low levels and engaged in asset purchases known as quantitative easing – that have gone beyond basic government bond purchases – to help lower longer term interest rates and incentivize more lending and borrowing activity.

Central bank “manipulation” often involves cynical and conspiratorial uses of the term by those who are ideologically against them. But outside of that, where there can be genuine manipulation (and identified by other countries as such) is with respect to domestic currency policy.

Governments are sensitive to governments manipulating their currencies because it can disadvantage them in terms of trade and global competitiveness. If one country is keeping its currency artificially low (print more of its own currency and buy other currencies), that can put other economies at a competitive disadvantage.

Under this concern, manipulation has been defined as a central bank purchasing foreign exchange in the market. This increases the value of those foreign currencies (or currency) relative to its own.

Its most incentivized to devalue relative to its most valuable trading partner. A cheaper currency creates cheaper goods in relative terms, allowing it to sell more.

Note that a weaker currency doesn’t impact domestic wages. Those remain the same. The price cut is effectively exported. This makes exports cheaper (helping manufacturers and domestic industry that exports its good offshore) and make imports more expensive (which can lead to inflation).

This is a common tactic in emerging markets that are in a stage of their development where they primarily rely on the export of their manufactured items, finished goods, and/or commodities or natural resources.

During the earlier stages of development, countries don’t have a well-developed services sector until the population becomes more educated. Once they do, they start developing a consumption-based economy.

Trade partners will typically not like and fight back at these currency manipulation practices in some, believing it hurts the competitiveness of their own goods in the global market. Moreover, it can effectively increase the prices that they have to pay for them.

As countries develop and restructure their economic models away from manufacturing and exported goods and toward services and consumption, central banks will generally prefer a stronger or more stable currency.

This is currently the case in China, for example.

When working to effectuate this policy (i.e., effectively reversing a weak currency policy), the central bank will want to sell foreign exchange reserves and buy its own currency.

This will work against manufacturers but help consumers, who now have greater purchasing power and importing goods becomes cheaper. Each unit of currency goes further.

This will usually reduce a country’s current account surplus accordingly, or increase its current account deficit if one exists.

How to avoid being impacted by central bank actions?

Having a well-diversified portfolio can help traders not be overly subject to swings in the credit cycle and monetary policy decisions that are out of their control and/or ability effectively analyze and bet on.

With respect to trading currencies, particularly on a longer term time horizon, it is important to understand where each nation is in its development.

Countries that are manufacturers and have an export-dependent economy may not necessarily want its currency to depreciate.

But it will have an interest in preventing its currency from becoming too strong. This will avoid undermining domestic manufacturers and entrepreneurs who can benefit by exporting their goods and/or services (i.e., based on their relative inexpensiveness to major trade partners and domestic consumers).

Accordingly, motivations are important and the central bank has a big role to play in a country’s currency. After all, they’re the ones who are responsible for money and credit creation.

Even in developed countries, many central banks want weaker currencies to help get growth and inflation up (e.g., notably the Swiss National Bank).

Conclusion

Market manipulation comes in various forms. In this article, we covered manipulation in the markets spanning from:

– Pump and dump

– False information

– Bear raiding

– Spoofing/painting the tape

– Wash trading

– Central bank manipulation (i.e., primarily currency devaluation and anti-competitive behavior)

Anywhere there is money, there is going to be participants in the market for it going to great ends to achieve their aims.

Many of these forms of market manipulation are regulated under securities laws. Some are in a legal gray area depending on their application.

Most of these are nonetheless short-term in nature. This includes tactics as pumping and dumping, spreading false information, and painting the tape (i.e., with fake trades).

Wash trading also doesn’t involve any directional price manipulation at all.

The best ways traders can protect themselves from these types of schemes is by focusing on longer time horizons (beyond a day or a few days) and by having a well-diversified strategic asset allocation.

Diversification improves a trader’s reward per unit of risk more than anything else they can practically do, which we can show mathematically.

Moreover, securities that are thinly traded and have small market capitalizations are the most prone to certain types of schemes. Relatively little money is needed to impact prices, therefore making them more vulnerable to soft or hard manipulation.

Highly speculative markets (e.g., 1999-2000, August 2020) also helps feed unscrupulous behavior.

During a speculative frenzy, the marginal cost of selling a new share (i.e., new equity capital) approaches zero. This leads to an increasing number of rent-seeking, fraudulent companies that get created to enrich their promoters who sell dreams and not economic earnings.