Can Deflation Ruin Your Portfolio?

What if deflation sets in and there’s not much that policymakers can do about it?

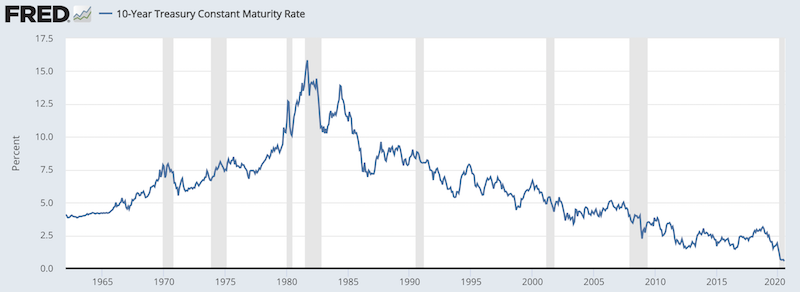

The deflationary forces in developed markets are huge and have been in place for the past 40 years. This has been a huge wind to the back of asset prices (through the present value effect) that’s now more or less out of gas.

There are a few main deflationary influences:

- High debt relative to income (i.e., if debt has to be paid it diverts away from spending on goods and services)

- Aging demographics (higher dependency ratios, increasing obligations relative to revenue)

- Offshoring production of various forms to more cost-efficient places, a drag on worker salaries

- Technological developments to increase economy-wide pricing transparency and reduce reliance on expensive labor

- Lower role for organized labor

Short-term and long-term rates are zero, and they’ve launched liquidity programs in conjunction with the fiscal spending arm of the government.

But there’s always the risk that that money and credit doesn’t get into goods and services spending and the huge deflationary forces win out.

Deflation as a positive force

A deflationary environment could also be a good thing for investors. Most people’s portfolios have a deflationary bent to them already being long equities and bonds.

Equities tend to do well when interest rates decline (at least when they interest rate offset is more than earnings are contracting). Drops in interest rates are beneficial for nominal rate bonds as well.

As noted, deflation has been a huge tailwind for US asset prices over the past 40 years. However, that’s more or less run its course.

As the US became more indebted, each cyclical peak and trough in interest rates became shallower to avoid debt service from swamping the cash flows.

Is cash a good asset to hold?

In some quantity, cash is good to hold as it gives liquidity and optionality in a portfolio.

But the policy response is in the other direction with large-scale easing. They’re trying to make cash as unappealing as possible. And they’re doing the same with bonds. The real returns of each are negative.

To sustain a highly indebted environment, where you need to make debt servicing low to avoid another contraction in the economy, you need to make both cash and bonds unattractive in both nominal and real terms.

Nominal bonds have flipped from an investment to something to be more neutral on as they don’t provide anything in the way of income. They can even be used as a financing vehicle in themselves to fund the purchase of other assets that will support borrowing or help in moving investors out over the risk curve.

So while cash is a good asset to hold in deflationary environments, it’s a bad asset to hold in inflationary environments.

When you don’t necessarily know which of those environments will win out (inflation or deflation), the timing, and the trend, then it really boils down to having balance in a portfolio. The range of unknowns are always high relative to the range of knowns relative to what’s discounted into the price.

In other words, the mix of deflationary assets to hold (e.g., cash, nominal rate bonds, many types of equities, corporate credit) against inflationary assets (e.g., gold, some commodities, inflation-linked bonds, some emerging market credit and equities) is about balance and overall diversification.

Policymakers’ ability and independence

There’s also the element of policymakers having wide latitude over what they can do.

It’s rare that they allow sustained deflations. This is especially true when they have fiscal policy they can monetize and their own currency they can create more of.

You can have a little bit of deflation. But cases where deflation becomes harmful – e.g., sustained high levels of unemployment, declines in economic activity – are generally rare when policymakers have the fiscal arm filling the gap and are not tied to any currency peg they are obligated to hold up.

The exception is when they’re stuck in a fixed exchange rate regime or stuck to a certain commodity like gold. They’re basically always successful in curing deflation when they don’t have artificial constraints.

Inflation targeting is the most foundational central banking practice, always set to a low, positive targeted figure or range. It is never set to a negative value as this means prices, production, income, wages, and spending will contract. Even if deflation is benign in nature – e.g., aggregate supply exceeding aggregate demand – this means output, wages, and spending aren’t being maximized.

Gold’s value in a deflationary environment

Moreover, gold is not only an inflationary asset, though that’s commonly how it’s thought of.

Gold is a type of reserve asset, or a monetary stability asset.

It tends to do well in environments of both deflation and inflation when the trend is out of whack relative to expectation.

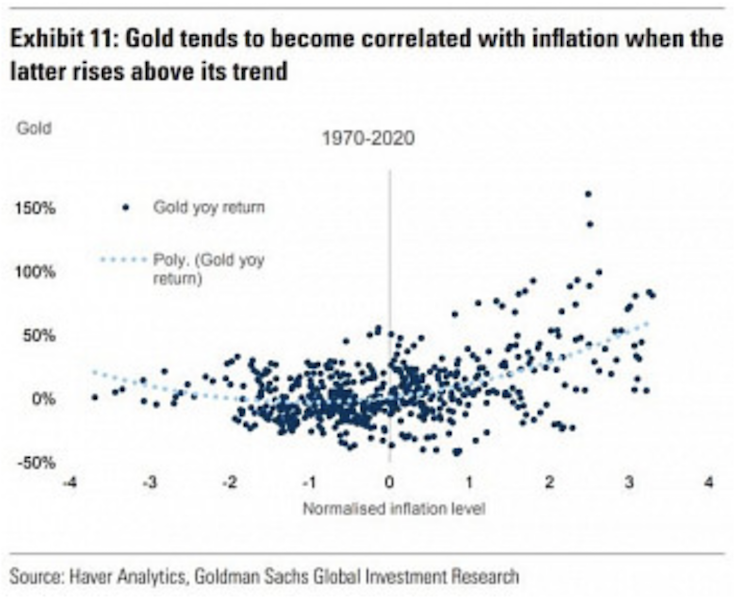

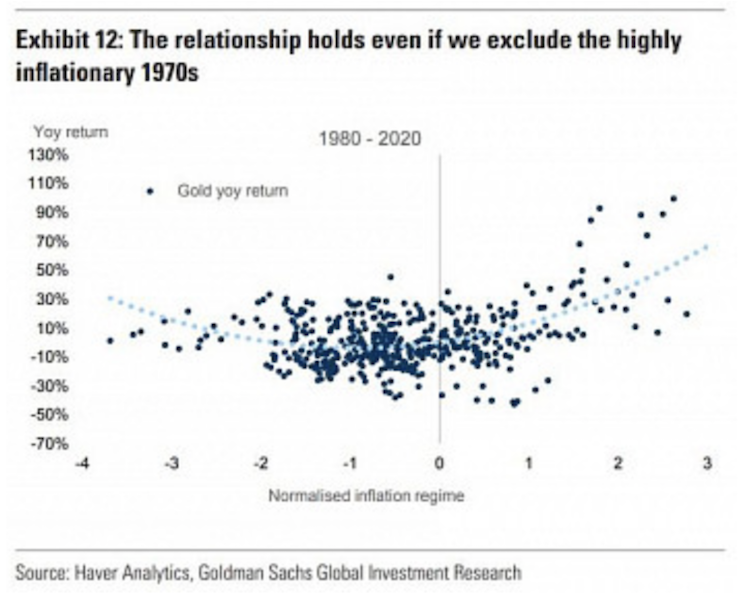

Goldman Sachs ran a study and found that gold’s price is sensitive to deviations in the inflationary trend, not when it’s specific to an absolute level.

Gold tends to keep its value over time because it’s priced relative to various fiat currencies; namely, a certain amount of fiat currency per troy ounce.

That makes gold effectively the inverse of money, or a reference point for the value of money. Therefore it tends to rise over the long-run (with plenty of short- and medium-term volatility) as the amount of currency and reserves in circulation rises over time.

When currency and bonds don’t yield anything and policymakers are “printing” a lot of money, people are less inclined to use those instruments as stores of wealth. They want to be compensated with a positive return (relative to alternatives ways of using the money) and don’t want to be paid back with deprecated money.

They’ll want to find something else that’ll hold its value better and doesn’t have credit or political risk.

Some of that gets into precious metals. And given they are relatively small, illiquid markets, it doesn’t take much to move their prices. The smallness and illiquidity can be a knock on the relativeness attractiveness of these markets, as they lack the capacity to take in large inflows of financial wealth.

The total value of the gold market is not even $4 trillion and silver is not even a $1 trillion market. This compares to credit and equity markets of about $350 trillion and $100 trillion, respectively. But in the event of wealth moving out of those markets because the returns are bad relative to the risks, they can boost the prices of the smaller precious metals markets in the event of a such a shift.

Because of its unique properties and societies and cultures attributing value to it, it’s been used as a store of wealth for thousands of years.

Gold’s relationship with inflation in not linear over time. It tends to not display a very strong correlation with inflation when it’s moderate. But it does begin to strongly correlate when inflation runs above a certain threshold.

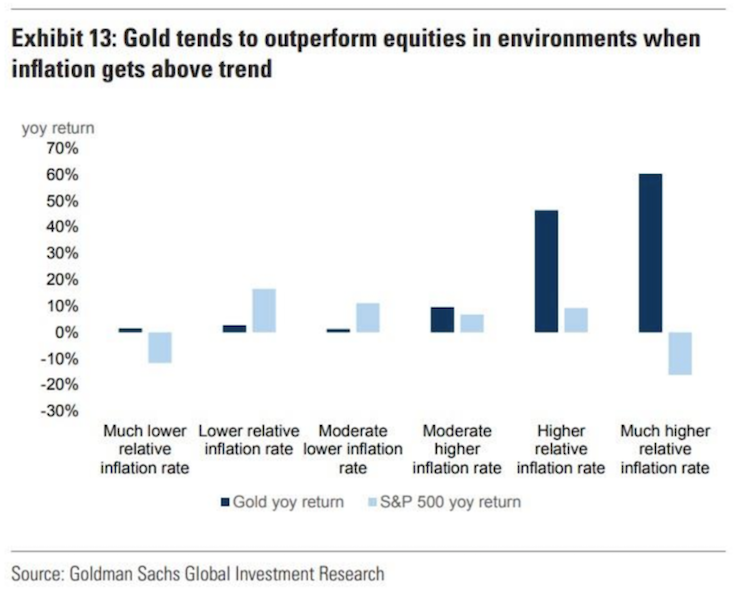

Goldman also looked at the performance of stocks and gold over prior inflationary environments.

The inflationary periods were broken up by looking at the deviation of year-over-year inflation rates against their rolling averages over the previous 10 years.

They found that gold did best when inflation surprised higher.

It also outperformed during deflationary periods.

Naturally, deflationary periods usually occur when business activity is materially cut back and debt servicing requirements compounded by drops in income create a fall in prices in both economies.

Namely, there’s a fall both in the prices of financial assets and in those of goods and services.

During these times, people are inclined to save more and keep their assets in cash and cash-like assets.

This can mean currency, short-term government debt, or safe havens like gold and other types of metals.

At the same time, it depends on the situation.

If people need cash to pay expenses or debts or need something highly liquid, that could also mean getting out of gold and safe havens.

In the 1930s, gold was considered one of the best places to store wealth. It could be redeemed at any time for a set amount of currency (at the time $20.67, or about $420 in today’s money). To get more liquidity in the economy to spur the recovery, President Roosevelt banished the ownership of gold through Executive Order 6102 in 1933.

That led to a surge in the price of gold. The same occurred in August 1971 when US President Richard Nixon took the US off the gold standard, effectively ending the Bretton Woods monetary system that had been established in 1944. Claims had built up that were in excess of gold reserves, making the USD-gold convertibility at a fixed $35 per ounce no longer feasible.

Gold finished the 1970s, a decade marked by high inflation, at $678 per ounce, a gain of 19.4x, or about 42.5 percent in annualized terms.

If economies are in a deflation, especially a harmful one, investors will recognize the need to get out of that and anticipate that policymakers will do whatever it takes.

In such cases, gold could be a good or at least a stable asset to have.

In major painful deflations (e.g., 1929-32 in most of the developed world, 2008), a gold and nominal bonds portfolio did very well.

2020 is unique because their yields are not the 3-4 percent they were during analogous situations when short-term interest rates were at zero. Now, longer-term rates are more or less stuck at zero as well.

But gold helped create balance not just to pick-ups in inflation, but as an asset that helps create stability during painful deflationary environments, not solely being an inflation asset.

Accordingly, more weight is shifting to alternative assets like gold and other precious metals (e.g., silver, which has done really well). And even quality stores of wealth like consumer staples equities, which are very likely to see steady earnings growth over time.

In sum, gold can be a useful asset to hold in some smaller quantity in both deflationary and inflationary environments.

Conclusion

Deflation is a risk, but it practically always is. Likewise, inflation is a risk with all the credit and liquidity support programs creating a lot of spending power at the same time supply in the economy contracted.

If asset prices are going to sustain such high levels, there needs to be higher economic growth.

It’s not likely going to come in the form of higher real economic growth (i.e., inflation-adjusted). Rather it’s probably going to have to involve higher nominal growth. The interest rate tailwind is gone.

Market participants can’t be too sure of what’s going to happen, when it will happen, and the general trend.

The best line of defense is a quality strategic asset allocation that can prepare them for all scenarios. One needs a portfolio that can efficiently earn various forms of risk premiums while mitigating the risk.

This means it’s not a bad idea to have diversification relative to different asset classes, to different geographies, and to different currencies.

This includes equities (developed markets, emerging markets), nominal bonds, inflation-linked bonds, commodities, gold and precious metals, different currencies (USD, EUR, JPY, GBP, CNY, etc.), and emerging market credit, while not being too concentrated in any given asset, location, or currency.