Psychological Biases in Trading & How to Avoid Them

Psychology is a big component of trading. The decisions we make are a product of the processing of the information that our brain takes in. This means that our psychological biases can have a big impact on our trading decisions.

There are many different psychological biases that can affect traders, but some of the more common ones are the gambler’s fallacy, confirmation bias, and loss aversion.

We’ll take a look at these fallacies and biases below.

Key Takeaways – Psychological Biases in Trading & How to Avoid Them

- Most Common Psychological Biases in Trading

- Gambler’s Fallacy

- Confirmation Bias

- Overconfidence Bias and Dunning-Kruger Effect

- Recency (Availability) Bias

- Anchoring Bias

- Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

- Blind-Spot Bias

- Authority Bias

- Acknowledge Common Biases

- We all experience reality in our own ways.

- Be aware of biases like Gambler’s Fallacy and Confirmation Bias that can distort your trading decisions and lead to losses.

- Stay Objective

- Regularly challenge your assumptions by seeking out contradictory evidence to avoid falling into the trap of belief or confirmation biases.

- This isn’t easy but can be trained over time.

- We all have biases, some of which we can become aware of and correct (if harmful) and others we’re less aware of.

- Think Long-Term

- Avoid Hyperbolic Discounting by focusing on long-term rewards instead of making impulsive decisions based on short-term gains.

- Seek Diverse Opinions

- Prevent Groupthink by considering diverse viewpoints and avoiding echo chambers that reinforce your existing beliefs.

- Always Be Learning

- Stay informed and always look to improve your skills, as overconfidence and the Dunning-Kruger Effect can lead to poor decision-making.

What Are Psychological Biases in Trading and Why Are They Bad?

Psychological biases are systematic patterns of deviation from rationality in judgment and decision-making.

These biases originate from deep-rooted adaptations and the relationship between domain-specific and domain-general thinking (covered below).

While they often helped our ancestors survive in uncertain and complex environments, they can lead to errors in reasoning in modern contexts.

Understanding the sources of these biases provides insight into why humans consistently misjudge probabilities, overestimate their abilities, and form illogical beliefs.

Domain-Specific Thinking vs. Domain-General Thinking

At the heart of many psychological biases lies a fundamental tension between two modes of thinking: domain-specific and domain-general reasoning.

Domain-Specific Thinking

This is our “fast,” intuitive, and largely unconscious way of processing information.

It relies on heuristics – mental shortcuts – that evolved to solve specific problems in our ancestral environments.

These heuristics are “domain-specific” because they were tailored to particular challenges, like finding food, avoiding predators, or navigating social hierarchies.

Domain-General Thinking

This is our “slow,” deliberate, and conscious reasoning.

It’s the capacity for abstract thought, logical analysis, and critical evaluation.

Domain-general reasoning is more flexible and adaptable, allowing us to solve novel problems and learn new information.

However, it’s also more effortful and requires training.

The core idea is that many biases arise when our domain-specific, evolutionarily-honed heuristics are applied to situations that are different from the environments in which they evolved.

Our brains, in essence, are using cognitive structures designed for the “Stone Age” to deal with the complexities of the 21st century and modern systems like financial markets.

Example: Pattern Seeking and its Modern Misfires

There’s a human tendency to seek patterns and causal relationships. This was incredibly valuable for our ancestors.

Recognizing that rustling leaves often preceded a predator, or that certain berries were poisonous, was crucial for survival.

This domain-specific adaptation hardwired us to find connections, even where they might be tenuous.

However, in the modern world, this same pattern-seeking tendency leads to several biases:

- Superstitions – A black cat crossing your path has no causal relationship with bad luck, but our pattern-seeking brain, primed to find connections, might create one.

- Conspiracy Theories – Complex events often have complex causes, but our brains crave simple, understandable narratives. This can lead us to embrace conspiracy theories – or explanations, in general – that offer a single, easily grasped (but often false) explanation.

- False Correlations – We might see patterns in random data (like stock market fluctuations) and attribute them to specific causes, leading to poor trading investment decisions. The gambler’s fallacy is a perfect example. Just because a roulette wheel landed on red five times in a row doesn’t increase the likelihood of it landing on black next – each spin is independent. But our brains, evolved to detect patterns in sequences, perceive a “due” outcome.

- Confirmation Bias – Once we seek a pattern, we tend to find it, even if the evidence against it is far greater. Confirmation bias is where people tend to favor information that confirms their existing beliefs or biases.

Our biases reflect our ancestral history, the limitations of our cognitive architecture, and, in essence, the fact that we have powerful brains that are nonetheless imperfect and susceptible to systematic errors.

This goes for everyone, which is why we need to stay humble and be mindful of our limitations.

Gambler’s Fallacy / Hot Hand Fallacy

The Gambler’s Fallacy is the mistaken belief that a particular outcome is more likely to occur because it has or has not happened recently, it is less likely to happen in the future.

This line of thinking is often referred to as the “hot hand fallacy”.

Gambler’s Fallacy Example

For example, let’s say you’re flipping a coin. The last five flips have all been heads.

You may be tempted to think that the next flip is more likely to be tails because heads have come up so often lately and things should balance out.

However, each flip of the coin is an independent event, and the probability of getting heads or tails is still 50% each time.

The Gambler’s Fallacy can lead people to make all sorts of bad decisions, like chasing their losses in gambling, because they think they’re due for a win and employing Martingale and other dangerous strategies.

Investors and traders can also fall prey to the Gambler’s Fallacy. For example, if stock prices have been falling for the past few days, some investors may think that it’s more likely that they will continue falling.

However, just because stock prices have fallen recently doesn’t mean that they are more likely to go down. Everything that is known is discounted into prices already.

When Is The Hot Hand More Likely to Be Correct?

There are cases where the hot hand is more of a gray area.

Baseball example

For example, let’s say a baseball player is batting .300 for the season (i.e., he successfully hits 3 out of 10 times he comes up to bat), but is 0-for-10 in his last 10 at-bats.

Is he “due” for a hit just because his performance has been so poor lately?

Just like flipping a coin, each at-bat in a baseball game is an independent event.

So it isn’t necessarily more or less likely a hit will happen on one at-bat versus another.

Obviously there are exceptions, such as being more likely to get a hit against a weaker pitcher relative to a strong one or being more likely to get a hit at home versus on the road.

So one could expect that there is a 70% chance that the 0-for-10 streak becomes 0-for-11 taking into account the overall body of performance.

However, there are cases where recent performance could be indicative of future performance.

For example, if the player is injured in some way that could reflect a new performance baseline until the injury gets better.

If a baseball player normally bats .300 and is 8-for-10 in his recent at-bats, does that mean he’s likely to perform worse to “even out” his batting average?

Or does it even mean his hot streak is likely to continue because he’s been hitting the ball so well?

There are cases where a player could genuinely be seeing the ball well, being in rhythm, and executing better. Or the competition could be weaker than normal over a short stretch.

Like many things in life, there is often a gray area and it may be hard to say with certainty whether the hot hand exists or not.

But in general, the Gambler’s Fallacy is still a fallacy because it assumes that past performance dictates future probabilities when, in fact, each event is independent in many scenarios.

The gambler’s fallacy is related to many other biases and fallacies as it pertains to behavioral economics.

Recency (Availability) Bias

The gambler’s fallacy is also related to the recency or availability bias.

This is the tendency for people to give more weight to recent information over older information when making decisions.

For example, if you’ve been on a winning streak in gambling, you might be more likely to think that you’re likely to continue to win because recent wins are still fresh in your mind. It might even be mistaken for skill.

You might be less likely to remember all of the times you’ve lost in the past because they happened further back and aren’t as salient.

Similarly, if you’ve had a string of bad luck recently, you may be more likely to think that it will continue because recent losses are still fresh in your mind.

This is why it’s important to be aware of biases when making decisions and to try to think objectively.

Anchoring Bias

The gambler’s fallacy is also related to anchoring bias.

Anchoring bias is the tendency for people to fixate on the first piece of information they hear (the “anchor”) and then make decisions based on that anchor, even if it’s not relevant.

For example, let’s say you’re asked to estimate the percentage of African countries in the United Nations.

If your first guess is 10%, you’re likely to anchor on that number and your second guess will be closer to 10% than if you hadn’t heard any number at all.

Similarly, in gambling, if you see that the person next to you just won a big jackpot, you may be more likely to think that it’s your turn to win because you’re anchoring on their recent success.

12 Cognitive Biases Explained – How to Think Better and More Logically Removing Bias

Overconfidence Bias

The gambler’s fallacy is also related to overconfidence bias.

Overconfidence bias is the tendency for people to overestimate their abilities and underestimate the likelihood of bad things happening.

For example, people often feel like they are better drivers than others, and that they are less likely to get into an accident.

However, the reality is that accidents happen all the time, and anyone can be involved in one.

Overconfidence bias can lead people to take unnecessary risks, and it can also make them less likely to prepare for worst-case scenarios.

For example, someone who is overconfident about their driving skills may not bother to get insurance, because they feel like they will never need it.

However, if they do get into an accident, they will be left with large bills that they might not be able to pay.

Overconfidence bias is a major problem in many areas of life, and it can have serious consequences.

People who are overconfident about their abilities often make poor decisions, and they may end up in situations that they cannot handle.

If you think you might be suffering from overconfidence bias, it is important to try to be more realistic about your abilities and the risks involved in various activities.

You should also make sure to prepare for worst-case scenarios, so that you will be able to cope if things do not go as planned.

Overconfidence bias is a big issue in trading.

When we are new to a subject, we don’t know what we don’t know. So it’s easy to be overconfident, which will inevitably lead to poor results.

This leads to our next phenomenon…

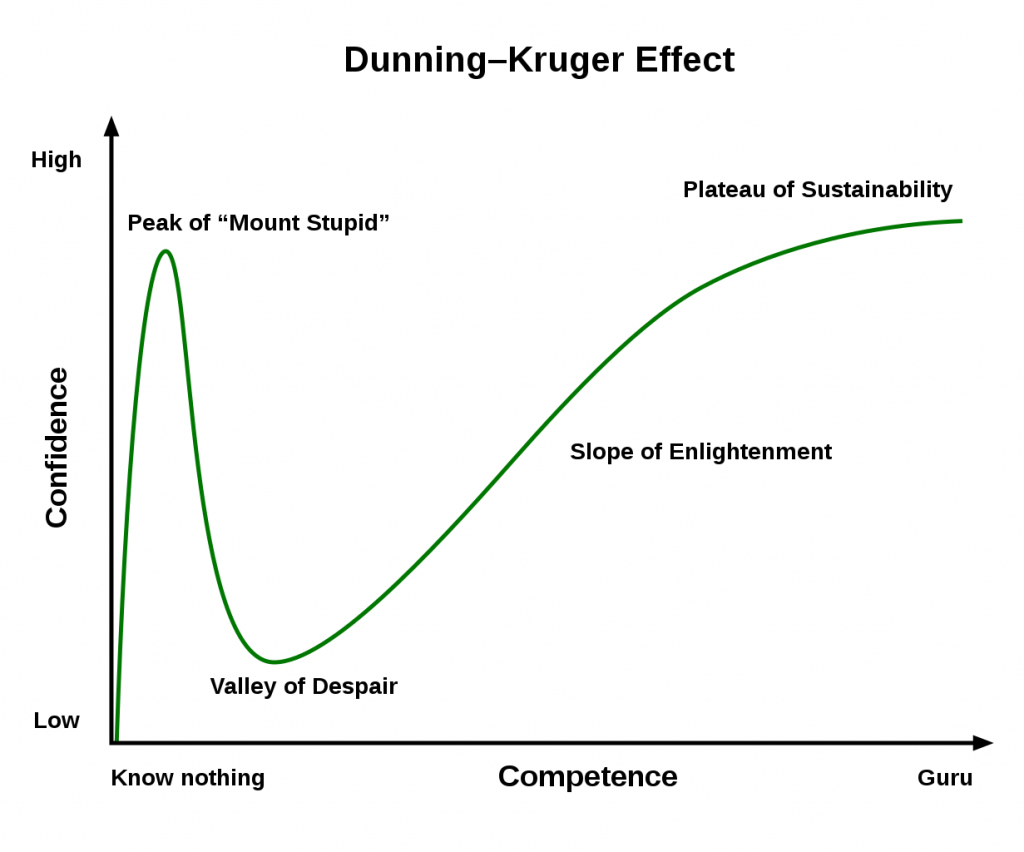

Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people who are unskilled at something tend to overestimate their abilities.

This is because they lack the ability to see their own shortcomings, and so they believe that they are better than they actually are.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is related to overconfidence bias, but it’s specifically about people who are unskilled.

People who are skilled at something tend to have a more accurate view of their abilities.

The Dunning-Kruger effect can lead to all sorts of problems, because unskilled people tend to make poor decisions.

They may take unnecessary risks or fail to prepare for worst-case scenarios.

A Bias of Self-Assessment

It highlights a key point:

The very skills needed to perform a task well are often the same skills needed to accurately assess one’s performance.

Imagine a novice chess player. They lack the strategic understanding, tactical awareness, and knowledge of openings and endgames that characterize an expert.

Because they lack this expertise, they also lack the ability to recognize their own deficiencies.

They might overestimate their abilities because they don’t know what they don’t know.

Conversely, a highly skilled chess player understands the immense depth and complexity of the game.

They are more aware of the subtle nuances, potential pitfalls, and vast range of possibilities.

This awareness can lead them to underestimate their abilities relative to others, as they are more conscious of their own limitations.

In essence, the Dunning-Kruger effect reveals that incompetence breeds overconfidence, while genuine competence can cause a degree of self-doubt.

This bias highlights the importance of seeking objective measures of performance and being wary of those who are overly confident in their own abilities, especially in domains where expertise is critical.

Dunning-Kruger effect plotted on a graph

The Dunning-Kruger graph shows the phenomenon of high overconfidence in those who are only marginally aware of something or have low skill.

For example, someone with very low skill or knowledge may have high confidence in what they know even though they barely know anything. This is because they don’t even know enough to be aware of what they’re missing.

As people become more skilled, they become more aware of what they don’t know, so their overconfidence subsides. This is especially true for complex tasks, such as trading, playing chess, and similar pursuits.

And as time goes on and they become more skilled and experienced, they begin to have a better understanding of what they know and what they don’t know.

Dunning-Kruger effect in trading

In trading, the Dunning-Kruger effect can lead to big problems.

If you are new to trading, you may overestimate your abilities and take unnecessary risks.

You may also fail to prepare for worst-case scenarios, such as the impact of painful drawdowns, and so you could end up losing a lot of money.

It is important to be aware of the Dunning-Kruger effect, and to try to be realistic about your abilities when you are starting out in trading.

If you are unsure about something, it is always best to ask for help from someone who is more experienced.

Make sure they’re fully informed and have a good track record in what you’re trying to understand.

Moreover, don’t make the mistake of having a confident opinion in subjects where you are not strong.

Trading Psychology | How to trade without biases and emotions?

Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

The Texas sharpshooter fallacy is a cognitive bias that leads people to search for patterns in data, even when there are none.

This is because people tend to see patterns where they don’t exist, and they may ignore evidence that contradicts their beliefs.

The Texas sharpshooter fallacy can lead people to make all sorts of bad decisions, because they are basing their decisions on false information.

For example, someone who believes in the Texas sharpshooter fallacy may think that they have found a winning investment strategy, when in reality they have just been lucky.

If they continue to invest based on this false belief, they will eventually lose money.

The Texas sharpshooter fallacy is a big problem in trading.

Many people who are new to trading believe that they have found the perfect strategy, when in reality they have just been lucky.

If they continue to trade based on this false belief, they will eventually lose money.

It is important to be aware of the Texas sharpshooter fallacy, and to realize that there is no such thing as a perfect investment strategy.

There is always some risk involved in trading, and you need to be prepared for the possibility of losses.

Superficial Judgments: The Perils of Incompetence

Superficial judgments are influential in areas where objective assessment is difficult, such as:

Politics

Voters may lack the expertise to evaluate complex policy proposals or the track records of candidates.

They might instead rely on superficial cues like charisma, appearance, or simple slogans.

This may lead them to support incompetent or even harmful leaders.

Investment Management

Some traders or investment managers may project an image of competence and success through confident pronouncements and presentations.

Some, lacking the financial expertise to critically evaluate their strategies or what they’re saying, might be swayed by these superficial displays, even if the underlying performance is poor or unlikely to be sustainable.

Other areas

These superficial cues are also prevalent in other matters, where self-proclaimed gurus may use their charm to sell fake or dangerous products, such as essential oils that “cure” illnesses.

Gish Gallop

Gish Gallop is not as much of a bias per se, as it is a rhetorical technique, but it’s nonetheless important to cover.

Gish Gallop is where a person rapidly presents a flood of misleading, false, or irrelevant statements, making it nearly impossible to refute each one in real-time.

It overwhelms the listener with sheer volume, allowing misinformation to take root.

It’s also sometimes known as Brandolini’s Law – i.e., it takes far more effort to debunk misinformation than to create it in the first place. This is a principle that disingenuous politicians and financial scammers know well.

The Danger of Gish Galloping in Financial Markets

In financial markets, especially in narrative-driven assets like long-duration equities, the Gish Gallop can be a powerful means for manipulation.

These assets – such as high-growth tech (or tech wannabe) stocks, speculative startups, and emerging technologies – derive much of their valuation from expectations about the future rather than present fundamentals. (Think Elon Musk.)

This makes them particularly vulnerable to misinformation, hype, and exaggerated claims.

Fraudsters and promoters exploit this by bombarding investors with grandiose claims about revolutionary products, disruptive business models, or astronomical growth projections.

This strategy of continuously pumping out a stream of overblown narratives creates a sense of inevitability around their investment thesis.

The sheer volume of positive but often misleading information makes it difficult for skeptics to counter each claim effectively.

Even when some points are debunked, the overall narrative persists because too many claims remain unchallenged.

This technique is particularly effective in bubbles and speculative manias, where excitement and FOMO (fear of missing out) override critical thinking.

Investors may be swept up by the hype, driving up stock prices based on unsustainable expectations.

When reality fails to meet these inflated promises, the inevitable crash leads to massive losses.

They might buy into the stock promotion and become active promoters of such misinformation because it also benefits them.

The media, PR firms, and other agents for the promoters can also pass along the narrative and lead to a social narrative that’s not popular to refute.

In outright frauds – like Ponzi schemes or pump-and-dump scams – the Gish Gallop helps perpetrators evade scrutiny long enough to extract capital from victims.

The “big breakthrough” is always just around the corner, which helps keep the stock remain high enough for long enough for fraudsters to still be seen as visionaries and use it as a springboard to gain more power and more wealth.

By the time reality catches up, insiders have already cashed out, leaving retail investors holding the bag.

In a world driven by narratives, misinformation spreads fast. The Gish Gallop exploits this, making it a dangerous weapon in financial markets.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the most prevalent psychological bias in markets that is actually acknowledged by traders themselves.

Some surveys have shown that 75% of all hedge fund managers admit to confirmation bias.

This type of bias is when an individual only seeks out information that confirms their beliefs while ignoring any evidence to the contrary.

Confirmation bias is dangerous because it can lead people to make bad decisions.

For example, someone who is biased towards a particular stock may only look for information that confirms their beliefs about the stock, and they may ignore anything that contradicts their views.

This can lead them to buy the stock even when it is overvalued, and they may end up losing money.

It is important to be aware of confirmation bias, and to try to look at both sides of an issue before making a decision.

If you are considering investing in a particular stock or any instrument, make sure to do your research and consider all of the evidence before making a decision.

It’s important to not just look for information that confirms your beliefs, but also look for information that contradicts your beliefs.

Only by looking at both sides of an issue can you make an informed decision.

Cognitive vs. Emotional Investing Bias

Cognitive biases are errors in thinking that lead to bad decisions.

Emotional biases are emotions that lead to bad decisions.

Both cognitive and emotional biases can lead to big problems in trading.

For example, someone who is suffering from overconfidence bias may take unnecessary risks, because they believe that they are better at trading than they actually are.

Someone who is suffering from the Texas sharpshooter fallacy may think that they have found the perfect investment strategy, when in reality they have just been lucky.

It is important to be aware of both cognitive and emotional biases, and to try to avoid them when you are making investment decisions.

If you are feeling overly confident or you are seeing patterns where there are none, it is always best to step back and take a more objective look at the situation.

It is also important to get help from someone who is more experienced, if you are unsure about something.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias occurs when individuals perceive past events as more predictable than they were.

After an outcome, traders often overestimate their prior knowledge, believing they “knew it all along.”

This illusion of predictability creates overconfidence, leading to riskier decisions.

For example, a trader might recall vague suspicions about a market crash as certainty after it occurs.

Such bias distorts self-assessment and discourages critical analysis of past decisions.

Over time, this can erode discipline, as traders rely on flawed memories rather than objective strategies, increasing exposure to future losses.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy describes persisting with failing trades or investments due to prior commitments of time, money, or effort.

Traders may cling to losing positions, hoping to recoup losses rather than evaluating current prospects.

Emotional attachment to past decisions overrides logic, often exacerbating losses.

For instance, holding a plummeting stock because “it cost me $10,000” ignores its present risks.

This fallacy traps capital in unproductive assets, hindering opportunities to reinvest wisely.

Overcoming it requires accepting losses as irreversible and focusing on forward-looking data.

Framing Effect

The framing effect highlights how presentation influences decisions.

Identical information framed differently – such as “80% success” versus “20% failure” – evokes varied responses.

Traders might embrace risk when outcomes are framed positively but avoid it when negatives are emphasized.

This bias can skew portfolio choices, as wording in analyst reports or media shapes perceptions.

Awareness of framing helps traders dissect information objectively, ensuring decisions align with facts, not phrasing.

For example, reframing a potential loss as a learning opportunity may reduce aversion to necessary risks.

Endowment Effect

The endowment effect causes individuals to overvalue assets they own.

Traders may resist selling underperforming stocks simply because they hold them, attributing irrational value to their holdings.

This attachment impedes rational portfolio rebalancing, such as refusing to set stop-loss orders.

For example, a trader might reject fair market offers for a stock, assuming its “special” potential.

Recognizing this bias encourages detachment, with decisions based on market realities rather than emotional ownership.

Disposition Effect

Disposition Effect is the tendency to sell winning investments or trades prematurely while retaining losers.

Driven by aversion to regret, traders “lock in” gains to avoid potential reversals but hold losses hoping for rebounds.

For instance, selling a rising tech stock too early limits upside, while clinging to a failing retailer deepens losses.

Overcoming this requires disciplined exit rules and separating emotions from performance analysis.

Herding (Social Proof)

Herding involves mimicking crowd behavior rather than independent analysis.

Traders may chase trends like meme stocks or panic-sell during downturns, ignoring fundamentals.

This drives market bubbles and crashes, as collective actions overshadow individual rationality.

For example, buying cryptocurrency during a frenzy due to FOMO (fear of missing out) often leads to buying high and selling low.

Combating herding requires sticking to predefined strategies and critically evaluating market narratives.

Outcome Bias

Outcome bias judges decisions by results rather than process.

A lucky win from a reckless trade may reinforce poor strategies, while a sound decision with bad luck is unfairly criticized.

For instance, profiting from an uninformed bet might encourage repeat behavior, despite long-term risks.

This bias obscures lessons from successes and failures, hindering improvement.

Traders have to evaluate decisions based on logic and data, not randomness-driven outcomes.

Self-Attribution Bias

Self-attribution bias credits successes to skill but blames failures on external factors.

A trader might boast about a profitable stock pick but blame Fed policies for losses.

This distorts self-assessment and prevents accountability and growth.

Over time, it inflates confidence and ignores systemic flaws in strategies.

Addressing this requires honest post-trade analysis, acknowledging both skill and luck in outcomes.

Traders ultimately have to understand the difference between variance/noise and signal.

Regret Aversion

Regret aversion is avoiding decisions to prevent potential regret.

Traders might skip promising opportunities fearing losses or delay exiting losers to avoid admitting failure.

For example, not investing in a rising market due to analysis paralysis.

This bias stifles action, leading to missed gains or compounded losses.

Mitigating it involves accepting uncertainty and focusing on probabilistic thinking rather than emotional outcomes.

Myopic Loss Aversion

Myopic loss aversion prioritizes short-term losses over long-term gains.

Traders hyper-focus on daily volatility, abandoning strategies after temporary downturns.

For instance, selling a diversified portfolio during a market dip despite its historical recovery.

This bias undermines patience, which is important for compounding returns.

Combatting it requires zooming out, setting long-term goals, and accepting volatility as part of growth.

Other Psychological Biases in Trading

Blind-Spot Bias

Traders might recognize biases in others but fail to see their own, leading to overconfidence in their decision-making process.

Authority Bias

Traders may give undue weight to the opinions of authority figures or experts, even when the information is questionable or irrelevant.

For example, while Albert Einstein was a world-class physicist during his time, applying a quote attributed to him outside of his sphere of expertise may not be prudent.

Pessimism Bias

Traders may focus more on negative outcomes or information, leading to overly cautious strategies and missed opportunities.

Belief Bias

Traders might accept or reject arguments based on their preconceived beliefs rather than on objective evidence, reinforcing existing biases.

Post-Purchase Rationalization

Traders may convince themselves that a poor decision was actually a good one, leading to continued poor decision-making.

False Consensus Effect

Traders might overestimate the extent to which others share their views.

May lead to misplaced confidence in their market predictions.

Contrast Effect

Traders may evaluate trades or market environments in comparison to recent experiences rather than on their own merits, which can lead to skewed perceptions.

Mere Exposure Effect

Traders may develop a preference for assets or strategies simply because they are more familiar with them, even if they aren’t the best options.

There’s a wide world out there in terms of opportunities.

Hyperbolic Discounting

Traders might favor short-term gains over more significant long-term rewards, leading to impulsive decisions and lower overall returns.

Risk Compensation

Traders may take greater risks when they feel more protected, such as when using stop-loss orders, leading to riskier behavior overall.

IKEA Effect

Traders may overvalue assets or strategies they have put effort into, regardless of their actual performance or potential.

Naïve Diversification

Traders may diversify their portfolio superficially, such as spreading investments equally across various assets without considering the correlation between assets.

For example, the stocks within market indices tend to move together because they all have similar environmental biases (e.g., they tend to fall when growth is lower than discounted and interest rates rise faster than what’s discounted.

So, it isn’t necessarily that well diversified.

Decoy Effect

Traders might be influenced by a less attractive option (decoy) to choose between two alternatives, skewing their decision-making.

Zero-Risk Bias

Traders might prefer options that seem to eliminate risk entirely – keeping a portfolio only in cash or short-term bonds – even if taking on some calculated risk could lead to better outcomes.

Sometimes the biggest risk is taking no risk.

And trading isn’t about eliminating risk but managing it well.

Placebo Effect

Traders might believe that certain strategies or indicators work better because they believe in them, rather than due to actual effectiveness.

Pro-Innovation Bias

Traders may overvalue new or innovative strategies simply because they are new, rather than because they’re proven to be effective.

Pseudocertainty Effect

Traders may prefer outcomes that are certain in specific scenarios (e.g., interest on cash and short-term bonds), even if taking on some uncertainty could lead to better overall results.

Reactive Devaluation

Traders might undervalue or dismiss ideas or strategies coming from sources they don’t trust or dislike, even if those ideas are sound.

Groupthink

Traders may conform to the decisions of a group, suppressing dissenting opinions, and leading to suboptimal decisions.

Just-World Hypothesis

Traders might believe that good or bad trading outcomes are deserved or inevitable, leading to complacency or a lack of accountability for poor decisions.

Fundamental Attribution Error

Traders may attribute their own success to skill and the success of others to luck, while attributing their own failures to external factors and others’ failures to personal mistakes.

Halo Effect

Traders might let one positive aspect of a stock or company (like a well-known CEO) influence their overall perception, leading to an overly favorable view of the investment.

In-Group Bias

Traders may favor opinions or strategies from their own peer group or community.

Can lead to an echo chamber effect that reinforces existing views.

Paradox of Choice

Traders may become overwhelmed by too many options, leading to indecision, analysis paralysis, or even regret after making a decision.

Law of Small Numbers

Traders might overgeneralize from a small sample of data, believing that a few examples or occurrences represent a reliable trend.

Strategies must be tested over a long enough timeframe.

How long?

We cover that here.

Planning Fallacy

Traders may underestimate the time, effort, and potential obstacles involved in executing a trading strategy.

May lead to missed deadlines or incomplete analyses.

Appeal to Tradition

Traders might stick to outdated methods or strategies simply because they’ve been used for a long time, even when newer approaches may be more effective.

Base Rate Neglect

Traders may ignore statistical base rates (general information) in favor of specific information, leading to decisions based on anecdotal evidence rather than broad trends.

Forer Effect (Barnum Effect)

Traders may believe that vague, general statements (often seen in technical analysis or market predictions) specifically apply to their situation.

This may lead to overconfidence in unreliable information.

For example, someone might say – “X isn’t a good investment” or “the market is going down” – without specifying a timeframe, being specific, mentioning alternatives, or simply explaining what data or reasoning their statement is based on.

How to Overcome Psychological Biases

Overcoming psychological biases is easier for some and harder for others.

Above all else, it’s important to be evidence-based.

All of our trading and investing decisions are based on data and information we take in and the processing of it.

Can you point to clear evidence supporting your decision?

Do you have a track record of success in the thing you are doing and have a clear understanding of the mechanics behind what you’re doing?

If you think you’re right, how do you know?

Have you sought out the thoughts and opinions of those who have knowledge on what you’re seeking to understand?

It can never hurt to hear another point of view. You’re just looking for the best answer, not simply the best answer you can come up with on your own.

It’s especially valuable when someone who is informed and credible disagrees with your view, as it represents the potential for learning if you can take in other information and view the evidence for and against each side.

Intellectually, people understand this by and large. But emotionally, it’s harder for some. They often view disagreement as conflict rather than an opportunity for learning.

In trading and investing, there will always be someone who disagrees with you. There is always someone on the other side of the trade.

You can never let emotions get in the way of making decisions.

It is also important to remember that no one has perfect knowledge, and that everyone makes mistakes.

Accepting that you will make mistakes, and that everyone else makes mistakes as well, and being able to learn from these mistakes is an important part of overcoming psychological biases.

And by doing so, we’ll be more likely to understand the importance of not being stuck in our own heads.

And to realize that, in markets, what you don’t know is always going to be greater than whatever it is that you know, and then understand how to manage this, such as having a balanced approach.

Trading Psychology: 10 Biases to Avoid

FAQs – Psychological Biases in Trading

What is the “hot hand”?

The gambler’s fallacy is the belief that if something happens often enough, it is bound to happen less often in the future.

For example, if a coin has been flipped 10 times and has landed on heads each time, someone who believes in the gambler’s fallacy might think that tails is due to come up on the next flip.

Of course, this isn’t true – each flip of the coin is a completely independent event, and the odds of flipping a head or a tail on a fair coin are always 50/50.

The hot hand is a related phenomenon, where people believe that if someone has had success in the past, they are more likely to have success in the future.

For example, a trader who has had a few winning trades in a row might think that they are on a “hot streak” and take on more risk than they should.

Both of these phenomena are examples of cognitive biases that can lead to bad decisions.

It is important to be aware of them, and to try to avoid them when you are making investment decisions.

What is the “Efficient Market Hypothesis”?

The efficient market hypothesis is the belief that all information is reflected in prices, and that it is impossible to beat the market, especially over the long-run.

This means that people who believe in the efficient market hypothesis think that it is impossible to find an investment that will outperform the overall market.

While the efficient market hypothesis is a popular theory, there is a lot of evidence that contradicts it.

For example, studies have shown that stocks with low price-to-earnings ratios tend to outperform the market over time.

This means that there are opportunities to beat the market, if you know where to look.

The efficient market hypothesis is a cognitive bias that can lead to bad decisions, because it leads people to believe that there is no point in trying to find investments that will outperform the market.

If you believe in the efficient market hypothesis, you may believe you can’t successfully add alpha to the markets over the long run.

Conclusion – Psychological Biases in Trading

Psychological biases can lead to big problems in trading.

The Gambler’s Fallacy, the Dunning-Kruger Effect, the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy, and Confirmation Bias are all examples of cognitive biases that can lead to bad decisions.

Emotional biases, such as overconfidence bias, can also lead to big problems.

It is important to be aware of all of these biases, and to try to avoid them when you are making investment decisions.

The best way to avoid these biases is to get help from someone who is more experienced, if you are unsure about something. And always be improving.

The more you know, the more you can approach your job in an evidence-based way.

You should also take a step back and look at the situation objectively, if you feel like you are suffering from any of these biases.

Related