Swap Spreads

A swap spread is the difference between the fixed rate on an interest rate swap and the yield on a government bond of the same maturity.

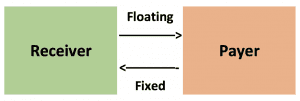

Interest rate swaps are financial instruments where two parties exchange cash flows. One party:

- pays a fixed rate, and the other

- pays a floating rate based on a benchmark like SOFR or EURIBOR

A wider spread suggests higher perceived credit risk in the private market relative to government debt.

Key Takeaways – Swap Spread

- The swap spread is a popular way to indicate credit spreads in a market.

- It’s defined as the spread paid by the fixed-rate payer of an interest rate swap over the rate of the “on-the-run” (most recently issued) government security with the same maturity as the swap.

- The spread captures the yield premium required for credit relative to the benchmark government bond.

- Because swap rates are built from market rates for short-term risky debt, this spread is a barometer of the market’s perceived credit risk relative to default-risk-free rates.

- This spread typically widens countercyclically – i.e., greater values during recessions and lower values during economic expansions.

- As such, traders often like shorting the spread (i.e., betting on it widening) as a hedge on their risk assets, assuming they can do it in an economical way.

Components of Swap Spreads

- Credit Risk – The primary component is the credit risk premium. Private entities are seen as riskier compared to governments, which can influence the spread.

- Liquidity Premium – This reflects the ease of trading in the swap market versus government bonds. Less liquid markets often have higher spreads.

- Market Supply and Demand – The balance between buyers and sellers in the market impacts swap spreads. High demand for swaps can tighten spreads, while excess supply can widen them.

- Economic Conditions – Factors such as inflation expectations, monetary policy, and overall economic health can affect swap spreads. For instance, during economic downturns, spreads typically widen due to increased credit concerns.

How to Calculate Swap Spreads

To calculate a swap spread, it’s straightforward:

- Identify the fixed rate on the interest rate swap for the desired maturity.

- Determine the yield on a government bond with the same maturity.

- Subtract the government bond yield from the swap fixed rate.

For example, if a 5-year swap fixed rate is 3% and the 5-year Treasury yield is 2%, the swap spread is 1% or 100 basis points.

Uses of Swap Spreads

- Pricing Fixed-Income Securities – Swap spreads help price other fixed-income securities by providing a benchmark for private borrowing rates.

- Measuring Credit Risk – Investors use swap spreads to gauge the relative creditworthiness of different issuers.

- Risk Management – Financial institutions manage interest rate risk using swap spreads to hedge against adverse movements in rates.

- Economic Indicator – Swap spreads serve as economic indicators, reflecting the market’s perception of economic stability and credit conditions.

Historical Context and Market Trends

Historically, swap spreads have fluctuated with economic cycles.

During the 2008 financial crisis, swap spreads widened significantly due to increased credit concerns and liquidity issues.

Conversely, in stable economic periods, spreads tend to narrow as credit risks diminish.

The transition from LIBOR to alternative reference rates like SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) also impacted swap markets and spreads – i.e., by aligning floating-rate benchmarks more closely with central bank policies and market liquidity conditions.

Impact of Monetary Policy

Central bank policies greatly influence swap spreads.

When central banks lower interest rates, swap spreads might narrow as borrowing costs decrease.

Conversely, rate hikes can widen spreads as the cost of borrowing increases, affecting both the fixed and floating legs of the swap.

Quantitative easing (QE) programs can compress swap spreads by increasing liquidity and reducing credit risk premiums.

However, tapering QE can have the opposite effect, leading to wider spreads.

But, of course, it depends on a range of factors.

Comparing Swap Spreads Across Markets

Swap spreads vary across different currencies and economies, reflecting local market conditions, credit environments, and regulatory frameworks.

For example, USD swap spreads are generally tighter due to the depth and liquidity of the US Treasury market.

In contrast, emerging market currencies often exhibit wider spreads due to higher perceived risks.

Trading Strategies Using Swap Spreads

Traders use various strategies leveraging swap spreads:

- Spread Ladder – Trading swaps with different maturities to benefit from a steep or flat swap curve.

- Curve Trading – Taking positions based on expected changes in the shape of the swap curve.

- Credit Arbitrage – Exploiting differences between swap spreads and other credit instruments to generate returns.

- Hedging – Using swaps to manage interest rate exposure and protect against unwanted rate movements.

So, overall, their ubiquity and versatility allow them to support various strategies, from hedging and risk management to speculative positioning and arbitrage.

Related

Risks Associated with Swap Spreads

Some risk associated with swap spreads:

- Counterparty Risk – The risk that the swap counterparty defaults on its obligations.

- Interest Rate Risk – Changes in interest rates can affect the value of the swap and the spread.

- Liquidity Risk – Difficulty in entering or exiting swap positions, particularly in stressed market conditions.

- Regulatory Risk – Changes in regulations can impact the swap market and spread dynamics.

I-Spread (ISPRD)

The term “swap spread” is sometimes also used as a reference to a bond’s basis point spread over the interest rate swap curve and is a measure of the credit and/or liquidity risk of a bond.

Here, a swap spread is an excess yield of swap rates over the yields on government bonds, and you use the terms I-spread, ISPRD, or interpolated spread to refer to bond yields net of the swap rates of the same maturities.

In its simplest form, the I-spread can be measured as the difference between the yield-to-maturity of the bond and the swap rate given by a straight-line interpolation of the swap curve

What Is an Interest Rate Swap?

Interest rate swaps (IRS) are a cornerstone of modern finance.

They represent the largest class of derivatives globally by notional value, estimated at around $500 trillion – or around ten times the size of the global government bond market on which they primarily reference.

Despite their vast scale, the basic mechanics of IRS are surprisingly straightforward, involving a simple exchange of cash flows between two parties.

At its core, an IRS is an agreement between two entities to exchange cash flows.

These cash flows are based on a notional amount, which is not exchanged but serves as a reference for the payments.

The two parties in an IRS are referred to as the Payer and the Receiver:

- The Payer agrees to pay a fixed interest rate, often referred to as a “coupon.”

- The Receiver agrees to pay a floating interest rate, which fluctuates based on a benchmark rate. The most common benchmark today is the SOFR, which closely tracks the Federal Reserve’s fund rate. Previously, LIBOR was the dominant benchmark but was phased out in.

Each period, the two parties “swap” payments: the Payer transfers the fixed rate, and the Receiver pays the floating rate.

This simple yet versatile arrangement forms the foundation for many more complex financial strategies.

Why Interest Rate Swaps Matter

Companies, banks, and institutional investors naturally use swaps to hedge against the risk of fluctuating rates, optimize financing costs, and achieve predictable cash flows.

But IRS also facilitate leveraged strategies, particularly in bond markets.

Leverage and Bond Markets

When traders want leverage in the Treasury bond market, they have several options:

Repo Market Financing

Investors can finance their Treasury purchases by borrowing in the repo market.

In this arrangement:

- The investor receives the fixed coupon from the Treasury bond.

- The investor pays the repo rate, which is typically tied to SOFR.

Bond Futures

Futures contracts allow investors to gain exposure to bonds without upfront cash outlay.

Sellers of futures often hedge by:

- Buying the reference bond.

- Financing it in the repo market.

- Receiving the fixed coupon and paying SOFR.

Bond futures, of course, don’t provide coupon payments and the cost of financing/leverage is implicit in the price of the contract (as is the case for equity futures and other markets).

Interest Rate Swaps

IRS offer a long-term alternative to the repo and futures markets.

By locking in the fixed rate for the life of the swap (often up to 30 years or more), the Receiver secures financing terms, while the Payer assumes the associated risks.

Pricing Interest Rate Swaps

The pricing of IRS reflects the market’s balancing act between supply and demand.

It also hinges on the inherent risks assumed by participants:

In Repo Markets

Investors who finance bonds assume risks related to SOFR variability and repo availability.

Pricing here is considered “fair” as it reflects market risks.

In Futures Markets

Buyers of bond futures lock in their implied SOFR rate and financing availability until the futures contract expires.

Sellers, however, take on the risk of SOFR changes and cash market dynamics during this period.

In IRS Markets

Receivers of fixed payments lock in financing terms for the swap’s duration, often spanning decades.

Payers take on the risk of SOFR changes and liquidity conditions, which can vary significantly over time.

Market Dynamics: The Role of Supply and Demand

Market conditions heavily influence the pricing and availability of IRS.

In normal environments, two-sided markets thrive with balanced supply and demand.

However, in times of heightened demand for leveraged long positions (such as futures or receiver swaps), dynamics shift:

Increased Demand

When the demand for leveraged positions outpaces supply, futures prices are bid up, and the fixed rates in IRS decline.

Hedging Pressure

As hedgers step in, they assume the risks of holding and financing cash bonds.

This intensifies the need for compensation in the form of higher cash-futures basis and swap spreads.

Liquidity Costs

The compensation demanded by liquidity providers – those willing to hold cash bonds and finance them – is reflected in the futures market basis and IRS pricing.

These costs rise sharply in environments where repo rates and liquidity risks are elevated.

What High Repo Rates & Swap Spreads Mean

High repo rates and swap spreads signal constrained liquidity and reduced demand for cash Treasuries relative to leveraged positions.

That kind of environment amplifies the cost of leveraging through swaps and futures, creating ripple effects across financial markets.

How Do Repo, ON RRP, and TGA Influence Swap Spreads?

Repo Market

Repos provide liquidity by allowing financial institutions to convert securities into cash, with repo rates directly influencing short-term borrowing costs.

The first-order relationship is that higher repo rates increase the financing cost of cash bonds, which narrows swap spreads as leverage becomes more expensive.

Nonetheless, the relationship is complex and influenced by factors like market liquidity, demand-supply dynamics, credit risk, and monetary policy.

ON RRP (Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreements)

The Fed’s use of ON RRPs sets a floor for short-term interest rates, stabilizing the federal funds rate.

Higher ON RRP rates anchor the floating leg of swaps like SOFR, impacting swap pricing and spreads.

Treasury General Account (TGA)

Fluctuations in the TGA balance impact bank reserves.

Rising TGA balances drain liquidity, tightening funding markets and potentially widening swap spreads as financing cash bonds becomes costlier.