Julian Robertson Trading Strategy & Philosophy

Julian Robertson (1932-2022) was the founder of Tiger Management, and is celebrated as one of the most influential figures in hedge fund history.

We look into his trading strategy, markets philosophy, and the lessons traders and investors can glean from his storied career.

Key Takeaways – Julian Robertson Trading Strategy & Philosophy

- Prioritize Deep Research – Exhaustive analysis forms the foundation of successful trades. Trade only when the odds are in your favor. He believed the best opportunities are lighter in number and infrequent.

- Embrace High-Conviction Investing – Identify undervalued opportunities and act decisively with bold, concentrated positions.

- Consider a Long-Short Strategy – Hedge risks by pairing long positions in strong companies with shorts in overvalued or declining ones.

- Look for Underexplored Markets – Focus on regions or industries with minimal competition and inefficiencies to maximize returns.

- Avoid Big Losses – Preserve capital through disciplined risk management and focus on sustainable, long-term gains.

Introduction to Julian Robertson

Julian Robertson’s legacy extends far beyond the returns generated during Tiger Management’s peak years.

Born in 1932 in North Carolina, Robertson launched Tiger Management in 1980 with $8.8 million in assets under management.

By 1998, the fund managed over $21 billion, delivering an astounding annualized return of 31.7% to its investors.

His approach was a fusion of deep fundamental analysis, calculated risk-taking, and contrarian thinking.

However, Robertson’s influence also stems from the network of protégés, famously called the “Tiger Cubs,” who carried forward his investment philosophy, establishing their own successful funds.

Core Tenets of Robertson’s Investment Philosophy

1. Value-Oriented Long-Term Investing

Robertson was a value investor at heart, focusing on identifying undervalued companies with strong fundamentals.

His methodology emphasized:

- Intrinsic Value – Robertson sought companies trading below their intrinsic value, often waiting for the market to recognize their true worth.

- High-Quality Fundamentals – Key metrics included low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, high free cash flow, and strong balance sheets (higher amounts of high-quality assets relative to liabilities).

- Patient Capital – He demonstrated a willingness to endure short-term losses if the long-term thesis remained intact.

2. Big Bets Based on Research

One of Robertson’s quotes is: “Smart idea, grounded on exhaustive research, followed by a big bet.”

He did not believe in spreading his portfolio thin but concentrated on high-conviction positions where the odds were substantially in his favor.

It’s also how most traders and investors of his generation approached things (being discretionary).

3. The Long-Short Strategy

Tiger Management employed a long-short equity strategy, balancing long positions in undervalued stocks with short positions in overvalued or structurally weak companies.

This hedging approach allowed Robertson to reduce risk while seeking alpha.

- For Long Positions – He looked for well-managed companies in growth industries.

- For Short Positions – He targeted businesses with poor management, declining industries, or irrational valuations.

Julian Robertson’s Key Strategies

1. Investing in Under-Researched Markets

Robertson believed in finding opportunities where competition was weak.

He emphasized venturing into regions or industries that were overlooked by the majority of investors.

“It’s easier to create the batting average in a lower league rather than the major league because the pitching is not as good down there.”

He was among the first to explore opportunities in markets like South Korea and Japan during their formative investment years.

2. Contrarian Positions

Robertson often took contrarian positions, betting against market trends.

During the late 1990s dot-com bubble, he refused to invest in overvalued tech stocks, even as the broader market rewarded such behavior.

Though this stance contributed to Tiger’s eventual closure, Robertson’s predictions about the bubble’s unsustainability proved correct.

The lesson: Valuations are a terrible short-term signal to trade on, but matter in the long run.

Robertson’s Approach to Fundamentals

1. Deep Company Analysis

Robertson demanded a high level of analysis before initiating positions.

His team looked at:

- Management Quality – Strong leadership was a non-negotiable criterion.

- Industry Trends – He evaluated the growth potential of sectors to identify future leaders.

- Valuation Metrics – P/E ratios, price-to-book ratios, and free cash flow were central to his evaluation process.

2. Macroeconomic Overlay

Robertson combined bottom-up stock picking with a top-down macroeconomic view.

He considered factors such as interest rates, currency movements, and global trade dynamics to inform his portfolio positioning.

Robertson put on currency positions as well (even famously losing a reported $2 billion in one day on a wrong-way bet against the yen).

Tiger Management: Successes and Challenges

Historical Performance

Between 1980 and 1998, Tiger Management delivered incredible returns north of 30% per year, making it one of the most successful hedge funds of its time.

They took advantage of opportunities across industries and geographies before it was popular to do so.

Challenges in the Dot-Com Era

By the late 1990s, Tiger Management faced significant headwinds:

- Value Stocks Out of Favor – As tech stocks soared, Robertson’s value-driven portfolio underperformed.

- Short Positions Painful – Overvalued stocks continued to climb, leading to losses on Tiger’s short positions. Even if the longs were doing what they were expected to, surging valuations in the short book were swamping the gains.

Robertson famously stated, “The only way to generate short-term performance in the current environment is to buy these stocks. That makes the process self-perpetuating until this pyramid eventually collapses under its own excess.”

Despite Robertson’s exceptional performance from 1980 to 1998, his fund is often more known today for its struggles and closure directly before the popping of the dot-com bubble.

Perhaps that itself was a contrarian signal.

The Birth of the Tiger Cubs

One of Robertson’s greatest contributions was his mentorship.

Many of Tiger’s former analysts went on to establish their own successful funds, collectively managing hundreds of billions in assets.

Known as the Tiger Cubs, these protégés include:

- Chase Coleman (Tiger Global) – Specializing in tech and growth stocks.

- Stephen Mandel (Lone Pine Capital) – A leading long-short equity fund.

- Andreas Halvorsen (Viking Global) – Focused on diversified equity strategies.

Key Lessons from Julian Robertson

1. Research is Non-Negotiable

Robertson’s success came from exhaustive research.

He believed that thorough due diligence was the cornerstone of informed decision-making.

2. Stick to Your Convictions

Even during periods of underperformance, Robertson held firm to his principles.

Value investing is what he knew and believed it would endure.

His decision to close Tiger Management in 2000 exemplified his integrity and refusal to chase unsustainable trends.

3. The Importance of Mentorship

Robertson’s emphasis on developing talent demonstrates the value of mentorship in creating enduring impact.

He then went on to invest in helping set up “Tiger Cubs” with their own funds who would have different ideas.

For example, he seeded Chase Coleman with $25 million for Tiger Global.

How to Apply Robertson’s Strategies Today

1. Focus on Fundamentals

Individual investors can emulate Robertson by prioritizing high-quality, undervalued companies with long-term growth potential.

Some metrics to focus on:

- P/E Ratio

- P/B Ratio

- Free Cash Flow (FCF)

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio

- Return on Equity (ROE)

- Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

- Earnings Growth Rate

- Gross Margin

- Operating Margin

- Current Ratio

- Dividend Yield

- EV/EBITDA

- Revenue Growth Rate

- Cash Flow from Operations (CFO)

- Net Profit Margin

2. Embrace Contrarian Thinking

Following the crowd rarely yields extraordinary returns.

Seek opportunities in overlooked or misunderstood sectors.

3. Hedge Your Bets

A long-short strategy, while complex, can help reduce market risk.

For those running institutional funds, then having a low correlation to the market so the return stream is differentiated from everything else is required.

Consider using exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or options to hedge exposure.

Quotes

Often the best way to look at someone’s strategy is here from the source themself:

“In May of 1980, Thorpe McKenzie and I started the Tiger funds with total capital of 8.8 million dollars. Eighteen years later, the 8.8 million had grown to 21 billion, an increase of over 259,000%. Our compound rate of return to partners during this period after all fees was 31.7%. No one had a better record.”

This quote highlights Julian Robertson’s unparalleled success during Tiger Management’s golden years.

Starting with modest capital, Robertson’s disciplined value-investing approach and strategic use of long-short equity strategies propelled the fund to extraordinary growth.

Now obviously a lot of the new growth was from new investment.

But if you had invested $100,000 in 1980, you would have had $14.2 million by 1998.

The 31.7% compound annual return reflected his ability to identify and take advantage of undervalued opportunities while effectively managing the risks associated with equity markets.

“The only way to generate short-term performance in the current environment is to buy these stocks. That makes the process self-perpetuating until this pyramid eventually collapses under its own excess.”

This quote captures Robertson’s critical view of the dot-com bubble.

He recognized that the massive rise in tech stock prices wasn’t sustainable but driven by speculative momentum.

Buying inflated tech stocks became a short-term strategy for many investors due to “FOMO,” (momentum-related sentiment) further inflating the bubble in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Robertson’s use of the term “pyramid” alludes to the fragility of such market behavior, predicting an inevitable collapse under its weight – with timing unknown.

He demonstrates his refusal to compromise his value-oriented philosophy, even at the cost of short-term underperformance.

He stuck to what he knew and was honest if his style wasn’t a good fit for the times.

“Some of these companies are selling at literally five and six times earnings and selling at two and three times cash flow. It’s just wild.”

In this quote, Robertson expresses disbelief at the extreme undervaluation – and relative valuation discrepancies – of certain stocks during the dot-com bubble.

While investors flocked to tech companies with little to no earnings, strong, cash-generating businesses were being ignored.

Companies trading at such low multiples represented clear value opportunities, yet they remained out of favor as market sentiment prioritized speculative growth over fundamentals.

His frustration showed the challenge of maintaining a disciplined strategy with widespread market euphoria.

This, of course, has always been a theme in financial markets, going all the way back to Isaac Newton’s famous quip over the South Sea bubble – “I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of the people.”

“Smart idea, grounded on exhaustive research, followed by a big bet.”

“Hear a story, analyze and buy aggressively if it feels right.”

These quotes illustrate Robertson’s philosophy of high-conviction investing.

For Robertson, success depended on identifying well-researched ideas with significant upside potential and then acting decisively.

“Smart idea, grounded on exhaustive research” reflects his belief in thorough analysis so that the odds were in his favor.

However, analysis alone wasn’t sufficient – Robertson emphasized the importance of decisiveness, as seen in “buy aggressively if it feels right.”

His willingness to “bet big” demonstrates the courage required to differentiate oneself in competitive markets.

It’s not unlike Stan Druckenmiller‘s approach to macro trading.

“Hedge funds are the antithesis of baseball. In baseball you can hit 40 home runs on a single-A-league team and never get paid a thing. But in a hedge fund you get paid on your batting average. So you go to the worst league you can find, where there’s the least competition. You can bat 0.400 playing for the Durham Bulls, but you will not make any real money. If you play in the big leagues, even if your batting average isn’t terribly high, you still make a lot of money.”

“It is easier to create the batting average in a lower league rather than the major league because the pitching is not as good down there. That is consistently true; it is easier for a hedge fund to go to areas where there is less competition. For instance, we originally went into Korea well before most people had invested in Korea. We invested a lot in Japan a long time before it was really chic to get in there. One of the best ways to do well in this business is to go to areas that have been unexploited by research capability and work them for all you can.”

“I suppose if I were younger, I would be investing in Africa.”

These quotes reveal Julian Robertson’s perspective on the importance of seeking underexplored markets and inefficiencies.

In baseball, playing at a lower level might not lead to financial reward, but hedge funds and trading are a different arena where success depends on finding and taking advantage of markets where competition is minimal.

Robertson believed that hedge funds do best by identifying and exploiting opportunities in less-researched areas, like playing in a “lower league” where the odds of success are higher.

The analogy of “batting average” highlights the value of consistent performance in hedge funds.

Even in the “big leagues,” where competition is fierce, outperforming marginally can yield substantial rewards.

However, Robertson’s strategy often focused on “lower leagues” of investing – i.e., emerging or less competitive markets where inefficiencies allowed for greater returns.

Examples include his early investments in South Korea and Japan before they became popular among institutional investors.

His success in these markets stemmed from the lack of competition and his ability to perform in-depth research, gaining an edge over other players.

Robertson’s mention of Africa reflects his belief in the potential of untapped markets. And without taking his Africa reference overly literally, it still is largely untapped.

He implied that young traders/investors should seek regions, areas, or opportunities with minimal institutional presence, where they could uncover hidden opportunities before mainstream capital floods in.

This can also apply to anything, not necessarily liquid markets.

This approach of going against the grain, whether geographically or by industry, was a cornerstone of his hedge fund philosophy.

“I believe that the best way to manage money is to go long and short stocks. My theory is that if the 50 best stocks you can come up with don’t outperform the 50 worst stocks you can come up with, you should be in another business.”

This quote shows Julian Robertson’s conviction in the long-short equity strategy.

The essence of this strategy is to take long positions in undervalued stocks while shorting overvalued or fundamentally weak stocks.

Robertson’s statement implies that an investor’s ability to identify winners (the “50 best stocks”) and losers (the “50 worst stocks”) is the true test of skill in active management.

His approach required not only selecting high-potential companies for long positions but also identifying stocks likely to decline, creating opportunities for profit on both sides of the market.

Or at least lower his beta to the market to differentiate his return stream from others as a relative value matter.

This balanced strategy hedges overall market risk, focusing instead on the relative performance of individual securities.

Robertson’s remark also carries a challenge to aspiring fund managers: if one can’t generate alpha (excess returns) by accurately distinguishing between strong and weak companies, active management may not be the right field.

For Robertson, stock-picking was a craft requiring deep research, conviction, and discipline.

This approach formed the foundation of Tiger Management’s success and continues to influence the strategies of his “Tiger Cubs” (many are equity managers and have their own focus).

“Avoid big losses. That’s the way to really make money over the years.”

This quote succinctly captures one of Julian Robertson’s core principles: capital preservation.

Drawdowns are the worst.

Avoiding significant losses allows an investor’s capital base to remain intact, which can better allow for compounding growth over time.

This approach aligns with the foundational investment principle of risk management.

Big losses can derail even the most skilled traders and investors.

And sometimes simply because of one mistake or betting wrong on a certain theme.

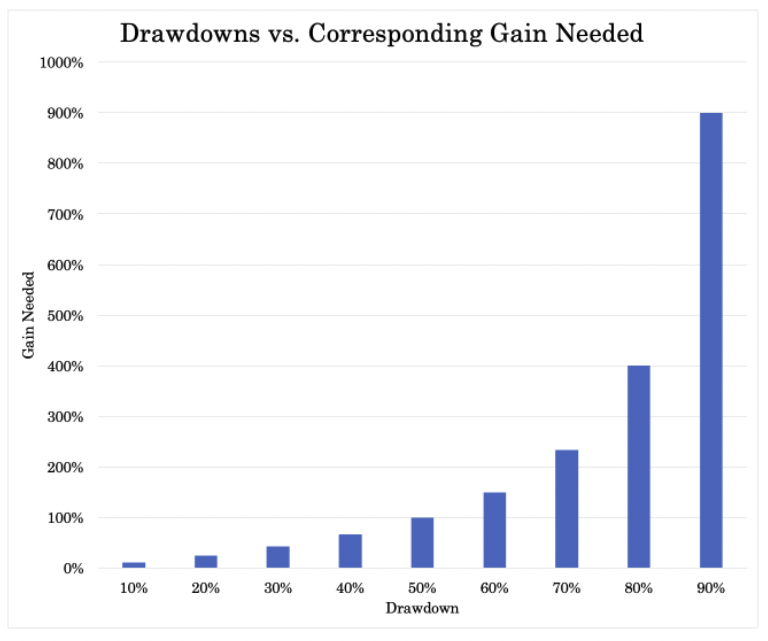

Recovering from a 50% loss requires a 100% gain, which shows the importance of protecting capital.

Robertson understood this mathematical reality and structured his strategies to reduce downside risks.

His long-short equity strategy exemplifies this philosophy, as the short positions acted as a hedge against market downturns.

Moreover, Robertson’s focus on high-quality companies with strong fundamentals reduced the likelihood of large losses in his long positions.

Prioritizing undervalued, stable businesses and avoiding speculative bets, he maintained a margin of safety.

For his short positions, targeting overvalued companies in declining industries added an extra layer of protection.

“For my shorts, I look for a bad management team, and a wildly overvalued company in an industry that is declining or misunderstood.”

This quote outlines Julian Robertson’s criteria for short selling, a key element of his long-short strategy.

Short selling involves betting against stocks expected to decline in value, and Robertson’s approach combined qualitative and quantitative factors to identify targets.

- Bad Management Team – Robertson believed that ineffective or unethical leadership significantly increased the likelihood of a company’s failure. Poor decision-making, lack of strategic vision, or a track record of mismanagement served as red flags. A track record of fraud as well (though these stocks can be dangerous because of the fraudster’s ability to promote them). This makes it more likely that underlying problems would persist.

- Wildly Overvalued Companies – For a short position to succeed, the stock must correct its inflated valuation. Robertson sought “wildly” overvalued companies, where market optimism had disconnected from reality. Such extremes provided greater downside potential, making the short position more likely to be profitable.

- Declining or Misunderstood Industries – Targeting industries facing structural challenges added a macroeconomic layer to Robertson’s short strategy. Declining demand, disruptive innovation, or regulatory pressures often compounded the struggles of overvalued companies in these sectors. Alternatively, misunderstood industries offered opportunities to capitalize on mispriced pessimism.

Robertson’s approach to shorting reflected his deep research ethos.

Aligning multiple factors – management issues, valuation excesses, and unfavorable industry trends – helped increased the odds of being right.

“There are not a whole lot of people equipped to pull the trigger.”

“I’m normally the trigger-puller here.”

These quotes reflect Julian Robertson’s emphasis on decisiveness in trading and investing.

Research and analysis are critical, Robertson recognized that the ability to act is important.

It can be easy to have good ideas, but it’s important to have the courage to act on them.

Robertson, as Tiger Management’s leader, took ultimate responsibility and accountability for decision-making.

This approach also required psychological resilience. Making decisive bets often involves significant risk and pressure.

“I’ve never been particularly comfortable with gold as an investment. Once it’s discovered none of it is used up, to the point where they take it out of cadavers’ mouths. It’s less a supply/demand situation and more a psychological one — better a psychiatrist to invest in gold than me.”

“Gold bugs, generally speaking, are some of the craziest people on the face of the globe.”

These quotes highlight Robertson’s skepticism toward gold as an investment.

He critiques gold’s unique nature as an asset: unlike stocks or businesses, it generates no income or intrinsic value over time.

Gold’s perceived value, in his view, is rooted in psychology and fear.

Gold has value because we perceive it has value.

This detachment from economic drivers made Robertson wary of its speculative nature.

His mention of psychiatrists and “gold bugs” underscores the views that often underpin gold investments, such as fear of inflation or distrust in currencies.

For Robertson, investing should be grounded in rational analysis and value creation, which gold, again, in his view, lacks.

Like practically all equity and credit traders/investors, they focus on productive assets.

But at the same time, as a long/short equity manager, that means that gold isn’t his wheelhouse.

It traditionally is an important market for global macro traders.

Gold functions as the inverse of money because its value often reflects changes in the value of currency rather than its own utility.

When central banks increase the money supply in excess of productive output, as they often do to manage debt or stimulate economies, the purchasing power of money typically declines.

As a result, gold’s price may rise in monetary terms – i.e., not because its intrinsic utility increases but because it takes more devalued currency to buy the same amount of gold.

In times of excessive money creation, gold can act as a hedge against currency devaluation (though it’s a weak hedge against inflation in the short run).

Accordingly, this can make it a useful portfolio component for preserving wealth.

Like with a lot of things, it’s a matter of perspective, trade-offs, and opportunity cost.

“When you manage money, it takes over your whole life. It’s a 24-hour-a-day thing.”

This quote captures the nature of professional money management.

Julian Robertson acknowledges the demands of overseeing large sums of capital, where every decision has consequences.

Markets shift constantly, requiring managers to monitor global events, trends, and portfolio performance.

The quote also notes the emotional intensity of the profession. Successes and failures can be deeply personal to many.

A career like trading, investing, and fund management demands not only skill and knowledge but also immense stamina and focus.

“I remember one time I got on the cover of Business Week as ‘The World’s Greatest Money Manager.’ Everybody saw it and I was kind of impressed with it, too. Then three years later the same author wrote the most scathing lies. It’s a rough racket. But I think it’s a good thing in human narcissism to realize you go from highs and lows based on your views from the press — really, it shouldn’t matter.”

This quote reflects Julian Robertson’s understanding of the fleeting nature of public opinion.

Being celebrated as “The World’s Greatest Money Manager” was a recognition of his extraordinary success, yet the same publication later criticized him harshly.

This illustrates the volatility of external perceptions.

Given the nature of media, the ups and downs are often typically overstated and sensationalized for commercial reasons.

For traders and investors, this serves as a reminder to focus on their own strategies and decisions rather than seeking validation from the media, public acclaim, or whatever it may be.

Market success comes with cycles of triumphs and setbacks.

Maybe your family doesn’t like your passion for trading or doesn’t understand it. Succumbing to external opinions can derail one’s focus.

And ultimately, people probably don’t have the information or full picture anyway.

Robertson’s lesson here is that resilience and humility are vital.

The media’s highs and lows are inevitable, but a trader’s success depends on staying committed to their principles and process, regardless of outside praise or criticism.

“[In March 2000] this approach isn’t working, and I don’t understand why. I’m 67 years old; who needs this? There is no point in subjecting our investors to risk in a market, which I frankly do not understand. After thorough consideration, I have decided to return all capital to our investors. I didn’t want my obituary to be ‘he died getting a quote on the yen.’”

This quote reveals Robertson’s integrity and self-awareness as an investor.

By March 2000, the dot-com bubble had upended markets.

It seemed to many like a new paradigm.

When you’re in a bubble, it’s not obvious to everyone.

Robertson acknowledged that his value-driven approach no longer aligned with the prevailing speculative trends.

Rather than jeopardize his investors’ capital in a market he couldn’t rationalize, Robertson made the decisive choice to close Tiger Management.

His humility in admitting what he did not understand and prioritizing his investors’ well-being over his reputation showed his commitment to principle and intellectual humility over ego.

For traders, this highlights the importance of knowing one’s limits and adapting to shifting market environments with honesty and discipline.

Incidentally, March 2000 also coincided with the top of the dot-com bubble and the start of a bear market that would last more than two years.

Conclusion

Julian Robertson’s investment philosophy and strategies remain as relevant today as they were during Tiger Management’s peak.

His ability to balance deep research, disciplined execution, and long-term thinking sets an enduring example for traders and investors.

Moreover, his legacy as a mentor means that his principles will continue to shape markets and hedge funds for decades.